Evaluation of the Management and Implementation of Agreements and Treaties

August 2022

Prepared by: Evaluation Branch

PDF Version (944 KB, 49 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| CIRNAC |

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

|---|---|

| CFP |

Collaborative Fiscal Policy |

| CLC |

Comprehensive Land Claim |

| IB |

Implementation Branch |

| IS |

Implementation Sector |

| M&I |

Management and Implementation |

| MTIO |

Modern Treaty Implementation Office |

| SGA |

Self-Government Agreements |

| SGIG |

Self-Governing Indigenous Groups |

| TAG |

Treaties and Aboriginal Government |

Executive Summary

Overview

The Audit and Evaluation Sector of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), led a mixed-methods evaluation of Management and Implementation (M&I) activities (i.e., the 'program') in accordance with CIRNAC's Five-Year Evaluation Plan and in compliance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act. The evaluation covered the period between April 2015 and March 2021. Activities and outcomes specific to provinces and territories, other government departments and agencies, the Modern Treaty Implementation Office (MTIO), and the Deputy Ministers' Oversight Committee were not in scope as they fall beyond the direct influence and control of the Implementation Branch (IB).

Overall findings and conclusions related to relevance, design and delivery, effectiveness, and efficiency of M&I activities are summarized below. Findings were triangulated across multiple lines of evidence, which included a review of program documents, files, grey literature, performance data, interviews with a total of 69 key informants and three case studies focused on best practices and emerging issues. Recommendations to support improvements in CIRNAC's approach to working with Indigenous partners and managing and implementing Treaties and Agreements follow.

Relevance

M&I activities align with the Government of Canada and departmental priority of reconciliation. There is a continuing need to ensure full and honourable, whole-of-government implementation of Treaties and Agreements, which mark the beginning of a new relationship between Indigenous signatories and the Crown and support reconciliation. Successful implementation of Treaties and Agreements also supports the Government's overall objective of improving the relationship with Indigenous Peoples based on rights, respect, cooperation, and partnership.

M&I activities are aligned with the continuing need for implementation coordination and expertise across the federal government, particularly in relation to managing intergovernmental relationships with Indigenous signatories and supporting other government departments to navigate implementation issues and fulfill their obligations. However, framing M&I as a 'program' and funding Indigenous signatories through program authorities may not reflect a true Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation approach given associated requirements and oversight that constrain Indigenous signatories' autonomy. Modern treaty and self-government arrangements are about an enduring intergovernmental relationship. The context of these relationships has changed greatly since the M&I program was established. Viewing the implementation of these agreements through a program lens does not adequately reflect the whole-of-government responsibilities set out in these Treaties and Agreements. If anything, the need for appropriate, effective, and efficient intergovernmental relationships will only grow with the finalization of new agreements for which implementation coordination responsibilities are likely to land with the IB.

Design and Delivery

Particularly due to recent organizational changes and an evolving understanding of what implementation requires, there is a need for greater clarity around implementation roles and responsibilities within CIRNAC and across the federal government. The extent to which IB personnel can advocate on behalf of Indigenous partners within the federal system and support a coordinated, whole-of-government approach to implementation is limited as a result.

Comprehensive mechanisms to fully and accurately assess IB resource requirements against defined roles and strategies and a fluctuating workload have not yet been established. Indigenous signatories are also insufficiently resourced to implement their obligations and respond to emerging implementation issues and opportunities, although emerging practices such as the Collaborative Fiscal Policy (CFP) development process and related offshoots (i.e., the M5Footnote 1 table and education annex) are being utilized to incrementally define and address unmet resource needs.

There are several challenges with the performance measurement system that limit CIRNAC's ability to generate valid and reliable information to support decision-making. While the IB has undertaken recent work to enhance performance measurement, further effort appears to be needed to delineate performance measurement needs and responsibilities for IB-specific versus whole-of-government implementation and to ensure that performance data reflects and assesses the intended intergovernmental relationships. For instance, some performance data were unavailable, incomplete, and/or untested. In addition, the M&I logic model and corresponding performance measurement data reflect some activities and expected outcomes that do not reflect the intergovernmental relationship with Indigenous partners. Meanwhile, the strength and effectiveness of working relationships and Indigenous partners' satisfaction with implementation were frequently identified as useful, but unmeasured, indicators of progress.

Effectiveness

Activities prioritized by the IB over the evaluation period were intended to support engagement of Indigenous partners and respond to their priorities, especially the need to redefine and evolve the fiscal relationship between Indigenous partners and Canada. While Indigenous partners' experiences varied, the evaluation found that M&I activities such as Implementation Committees, the CFP development process, and the COVID-19 Working Group contributed to improvements in relationships by providing opportunities for Indigenous partners and federal government representatives to develop and maintain positive working relationships, engage in two-way conversations, address issues and concerns, collaborate, and build trust. Leading or supporting training sessions, conducting outreach to other government departments, and providing opportunities for other government departments to engage with Indigenous partners also contributed to improvements in federal officials' awareness of Treaties and Agreements and their capacity to fulfill obligations.

M&I activities and the IB indirectly contributed in supporting Indigenous governments and groups to the extent that they supported full, honourable implementation of Treaties and Agreements, responded to Indigenous partners' needs and priorities, and provided Indigenous partners with resources to implement their obligations, self-govern, and address underlying inequities. Work is ongoing to address Indigenous signatories' unmet resource needs.

Indigenous partners with higher levels of satisfaction with M&I activities tend to be those who experienced greater responsiveness to their needs and priorities. However, Indigenous partners overall have not been consistently experiencing a timely, whole-of-government response to implementation issues or other priorities, and stakeholders expressed a clear desire for enhanced accountability. Other factors that have limited Indigenous partners' satisfaction with implementation include resourcing constraints, insufficient coordination across the federal government, implementation delays, narrow or restrictive interpretations of Treaties and Agreements, federal turnover and lost corporate memory, and limitations in the extent of partnership offered by Canada. Further efforts are needed to spread awareness of Treaties and Agreements across government and ensure that officials are fully equipped to understand and respond to department-specific as well as whole-of-government obligations and issues. There is also an opportunity for the IB to develop in-house subject matter expertise related to common implementation issues (e.g., fiscal matters, impact assessments, fisheries) or to establish stronger links to implicated other government departments to develop issue-specific implementation expertise.

Efficiency and Economy

Establishing a new department and sector required a significant investment of time and resources. There are opportunities to strategically analyze IB activities to identify efficiency improvements that can support the IB to better work with other government departments and Indigenous partners to further support a timely, coordinated response to implementation issues as well as fulfilment of Canada's obligations. There may also be opportunities for the IB to develop in-house subject matter expertise or establish stronger links to other government departments, which could enhance efficiency by providing means for the IB and other government departments to better leverage existing knowledge, capacity, and lessons learned through prior experiences.

Finally, given the significant time and resource requirements of emerging practices such as the CFP development process, there is a particular need to assess when and how they can be utilized to best support implementation and address Indigenous partners' resource needs while also respecting the opportunity costs they present. In doing so, there is a need to centre partners' priorities and cost-benefit considerations so that Canada's approach, facilitated by the IB, can allow for meaningful involvement and support the intended nation-to-nation, Crown-Inuit, and government-to-government relationships and self-determination.

Recommendations

Based on evaluation findings and conclusions, it is recommended that CIRNAC:

- Lead collaborative work to move away from a programmatic approach to the implementation of Agreements and Treaties to an approach that reflects the enduring and evolving nature of intergovernmental relationships.

- Undertake a comprehensive analysis of implementation roles & responsibilities, resources, processes, and linkages to partners and stakeholders, in order to strengthen the implementation of Modern Treaties and Agreements and to fully reflect the intergovernmental relationship.

- Collaborate with Self Government and Modern Treaty partners to develop data options that reflect self-determination and facilitate the integration of this data and approach by whole-of-government when designing new programs and other initiatives.

- Determine that emerging mechanisms (such as CFP) should be used to better enable Self Government and Modern Treaty partners to contribute to Government of Canada decision making processes and to foster the intergovernmental relationship.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Management and Implementation of Agreements and Treaties

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan has been developed to address recommendations made in the Evaluation of the Management and Implementation of Agreements and Treaties.

The Implementation Sector (IS) welcomes the important findings and recommendations of this report. Many of the recommendations put forward will need to be addressed cohesively by the Implementation Sector even though the report itself is focused almost exclusively on one of the three branches within Implementation Sector (Implementation Branch). The reason for this focus is linked to the Policy on Results and associated programs. The Policy was established in 2016, prior to the creation of the Implementation Sector, when IB existed as a branch within Treaties and Aboriginal Government (TAG). As the volume and complexity of implementation issues have increased over the past several years (e.g., volume of agreements to be implemented, new authorities related to treaty renewal, new programs, policies and legislation that impact modern treaty and self governing groups such as Child and Family Services and United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), there has been a continual need to revisit where the work rests within the sector and thus our recommendations are focused at the sector level as opposed to the branch level. This level of response allows us to set ourselves up internally in the most efficient manner possible, within the confines of existing resources, to meet expectations of our modern treaty and self governing partners. Our hope is that the growth will allow us to be able to better grapple with whole-of-government implementation challenges, while ensuring that individual implementation matters, such as treaty renewals and implementation committees, can continue to be addressed through the direct relationships with implementation coordinators and managers. This is in line with CIRNA's current mandate commitment to support Indigenous-led processes for rebuilding and reconstituting their nations and advancing self-determination, and work in partnership on the implementation of the spirt and intent of treaties, and land claim and self-government agreements with appropriate oversight mechanisms to hold the federal government accountable.

The Evaluation acknowledges limitations to evaluating Management and Implementation activities that fall beyond the scope of the evaluation, and a challenge to distinguish work done by Implementation Branch from those of other parts of the Implementation Sector and Treaties and Aboriginal Government (TAG) Sector. Moving forward, the action plan includes a commitment to continue to build critical feedback loops between IS, TAG and other sectors, and other federal departments. Moreover, this evaluation builds on work underway to address Action Plan associated with the 2020 Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, which was undertaken as per requirements in the Directive. The combined results of these evaluations, and their associated action plans, will help to bolster the work of the Implementation Sector.

Indigenous signatories enter into treaties and self-government agreements with Canada with the expectation that Canada will meaningfully implement its agreement obligations in a manner that respects the Honour of the Crown. This relationship, led by CIRNAC, is perpetual and enduring in nature, and takes into account the evolving nature of new federal policies or legislation impacting Indigenous signatories, the transfer of program authorities, as well as ongoing attainment of Indigenous partners' interests and objectives.

Although the evaluation is clear that other government departments (OGDs) were not considered in the original scope, their role in implementation is critical. Over 30 federal departments have direct implementation obligations outlined in treaties, and all federal departments need to be aware of whole-of-government obligations, such as specific procurement and consultation obligations.

The scope of this evaluation commenced in 2015. Since then, Canada's relationship with Indigenous Peoples has evolved greatly. As the journey of reconciliation continues, more and more unique arrangements honouring nations unique self-determination goals will come into effect and require implementation support. In order to successfully implement current and forthcoming agreements, as well as to implement the recommendations put forward within this evaluation, Implementation Sector will need support across government to ensure that other departments are aware of, and have the capacity to meet their obligations within each agreement. This equally applies within CIRNAC, as the successful implementation of these agreements involves close collaboration with subject matter experts in other sectors.

The action plan has been developed with a view towards ensuring the proposed measures represent appropriate and realistic efforts to address the evaluation. A number of key initiatives that align with the recommendations of this evaluation are already underway.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lead collaborative work to move away from a programmatic approach to the implementation of Agreements and Treaties to an approach that reflects the enduring and evolving nature of intergovernmental relationships. | a) Implementation Sector will work with modern treaty and self government partners to co-develop and jointly advance proposals to ensure the unique nature of modern treaty and self government agreements are appropriately considered in the policy development process. |

Director General, Implementation Branch Director General, Policy, Planning and Coordination Branch |

a) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Summer 2023 |

| b) Implementation Sector will leverage the Assessment of Modern Treaties Implications (AMTI) process and governance structures, including the Deputy Ministers’ Oversight Committee and Directors’ General Implementation Committee, to strengthen the whole of government approach to modern treaty implementation. | b) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Winter 2023 |

||

| 2. Undertake a comprehensive analysis of implementation roles & responsibilities, resources, processes, and linkages to partners and stakeholders, in order to strengthen the implementation of Modern Treaties and Agreements and to fully reflect the intergovernmental relationship. | a) Implementation Sector will work with the Chief Finance, Results and Delivery Office, and Treaties and Aboriginal Government sectors to develop and recommend a new process that facilitates the feedback loop between Implementation and Negotiation phases of agreements to fully consider Implementation resourcing requirements well in advance of agreements being finalized. | Director General Implementation Branch Director General, Policy, Planning and Coordination Branch |

a) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Winter 2023 |

| b) Implementation Sector will continue to work with central agencies and other government departments to strengthen knowledge of unique nature of modern treaty, self-government, and other constructive arrangements. | b) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Fall 2023 |

||

| c) Implementation Sector will modernize its structures to ensure that staffing and organizational structures can support long-term implementation. | c) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Spring 2023 |

||

| 3. Collaborate with Self Government and Modern Treaty partners to develop data options that reflect self-determination and facilitate the integration of this data and approach by whole-of-government when designing new programs and other initiatives. | a) Implementation Sector will support modern treaty and self-governing partners data sovereignty, including through work on the Data Governance and Management Toolkit. | Director General, Implementation Branch Director General, Policy, Planning and Coordination Branch |

a) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: TBD |

| b) Implementation Sector will consult with the Results and Delivery specialists to seek recommendations on appropriate and effective ways to integrate data and performance indicators that is reflective of self-determination, in whole-of government design of new programs and initiatives. Implementation Sector will share these recommendations with OGD to assist them in the development of their own internal tools for integrating this data in the design of their own programs and initiatives. | b) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Spring 2023 |

||

| c) Implementation Sector will evaluate existing tools within CIRNAC, such as the Modern Treaty Management Environment system, for their usefulness in strengthening federal accountability and performance reporting for the implementation of modern treaty and self-government agreement obligations. | c) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Winter 2024 |

||

| 4. Determine what emerging mechanisms (such as CFP) should be used to better enable Self Government and Modern Treaty partners to contribute to Government of Canada decision making processes and to foster the intergovernmental relationship. | a) Implementation Sector will work with Treaties and Aboriginal Government and modern treaty and self-governing partners through the Collaborative Fiscal Policy Development process and other venues to develop methodologies to identify and address socio-economic gaps. These methodologies will support evolution of Canada’s Collaborative Self-Government Fiscal Policy and advance self-government as a viable path away from the Indian Act. | Director General, Implementation Branch Director General, Policy, Planning and Coordination Branch |

a) Start Date: Ongoing End Date: Ongoing |

| b) Implementation Sector will work with partners to consider ways in which the annual reporting process could be streamlined in order to lessen the burden of reporting requirements. | b) Start Date: Summer 2022 End Date: Summer 2023 |

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Overview of Treaties and Agreements

There have been four phases of treaty-making in Canadian history: commercial compacts; Peace and Friendship Treaties; Historical Treaties; and Modern Treaties.Footnote 2 Since 1975 when the first Modern Treaty was signed, Treaties and Agreements have been negotiated based on two federal government policies that provide the foundation for how Canada negotiates with rights holders under Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982:

- The Comprehensive Land Claims Policy (1986), with origins dating back to 1973, specifies that land claims may be negotiated in areas where claims to Indigenous title have not been addressed by Historical Treaties or through other legal means. Modern Treaties, also known as Comprehensive Land Claims (CLCs), are based on the assertion of continuing Indigenous rights and titles. They are tripartite constitutionally protected agreements that provide clarity and predictability with respect to the ownership and management of land and resource rights and serve as living relationships that advance a broad set of objectives in support of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

- The Inherent Right Policy (1995) recognizes the inherent right of Indigenous Peoples of Canada to govern themselves in relation to matters internal to their communities, integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, languages, and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and resources. Self-Government Agreements (SGA) negotiated under this policy are legally binding arrangements that give practical effect to the inherent right of self-government by setting out the structure and resources for Indigenous governments to govern their internal affairs and assume greater responsibility and control over the decision-making that affects their communities. SGA may be standalone or included as part of a CLC. Sectoral agreements are a related option that establish self-government over specific jurisdictions, such as primary and secondary education.

CLCs, SGA, and Sectoral agreements generate new nation-to-nation, Crown-Inuit, and government-to-government relationships and significant changes to the political and socio-economic landscape. They are also accompanied by new federal funding for implementation costs incurred by Indigenous signatories and federal departments in fulfilling agreed obligations as well as for any statutorily protected settlement benefits (including financial transfers to designated Indigenous governments / groups).Footnote 3

As of March 2018, there were 32 completed Treaties and Agreements involving 53 First Nations, 46 Inuit communities, and three Métis communities corresponding to:

| 18 | CLCs with SGAs | 4 | Standalone SGAs (no CLC) |

| 7 | CLCs without SGAsFootnote 4 | 3 | Sectoral agreements |

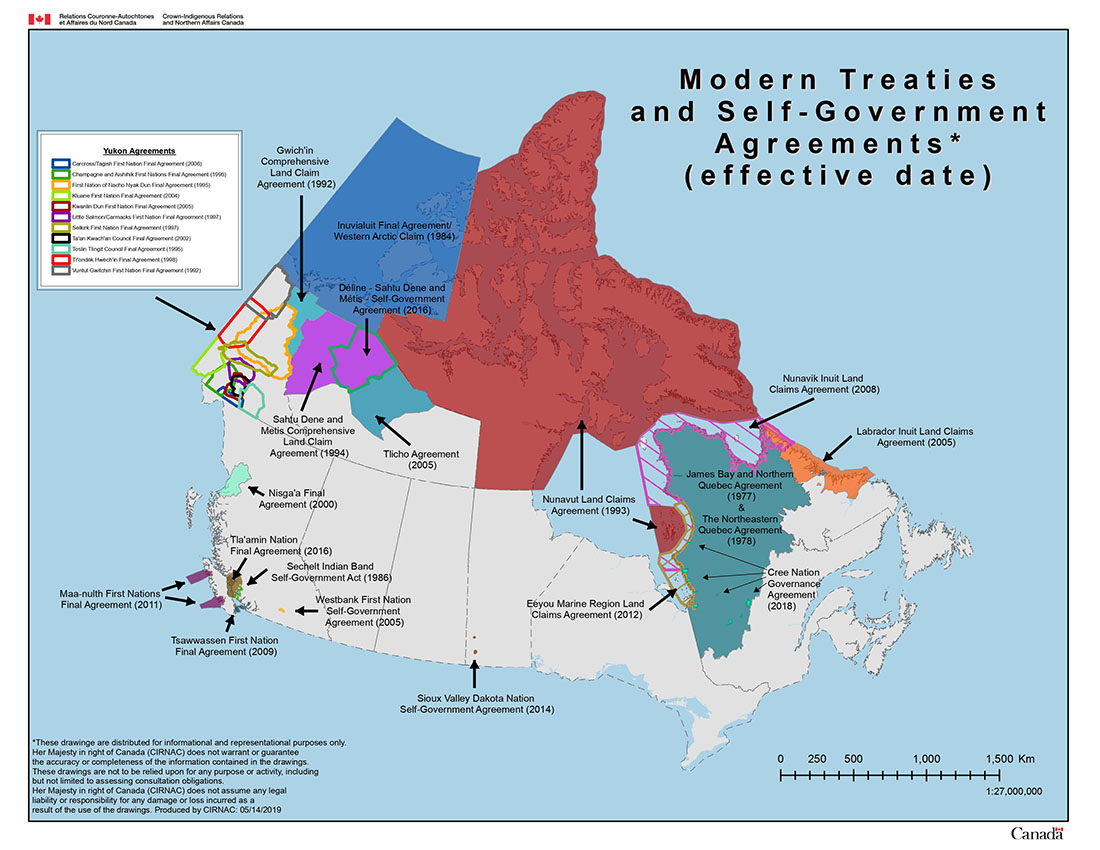

Figure 1 shows the distribution of completed CLCs and SGA across Canada (including standalone SGA), as well as the effective date of each.Footnote 5 Sectoral agreements are not pictured.

Figure 1 : Map of Modern Treaties and Self-Government Agreements

Detailed text description of Figure 1 : Map of Modern Treaties and Self-Government Agreements

Figure 1 shows the map of modern treaties and self-government agreements on the map of Canada, along with the date they were made effective.

In Newfoundland, there is the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement effective from 2005.

In Quebec there is the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement effective 1977; the Northeastern Quebec agreement effective in 1978; and the Cree Nation Governance Agreement effective 2018.

Overlapping Newfoundland, and some of the Hudson’s Bay is the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement effective 2008.

On the border of Quebec and Hudson’s Bay, is the Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement, that was made effective in 2012.

Encompassing Nunavut is the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, effective 1993.

In Manitoba, there is the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Self-Government Agreement, made effective in 2014.

In British Columbia, is the Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement, effective 2005; the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement, effective 2019; the Sechelt Indian Band Government Act effective 1986; the Tla’amin Nation Final Agreement, which was made effective in 2016; the Nisga’a Final Agreement, effective the year 2000; and lastly, the Maa-nuith First Nations Final Agreement on Vancouver Island, effective 2011.

In the Yukon, there are eleven agreements. The Kluane First Nation Final Agreement, effective 2004; the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Final Agreement, effective since 1995; the Carcross/Tagish First Nation Final Agreement, effective 2006; the Kwanlin Dun First Nation Final Agreement, effective 2005; the Ta’an Kwach’an Council Final Agreement, effective 2002; the Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation Final Agreement, effective 1997; the Teslin Tlingit Council Agreement, effective 1995; the Selkirk First Nation Final Agreement, effective 1997; the First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun Final Agreement, effective 1995; the Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Final Agreement, effective 1998; and the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Final Agreement, effective 1992.

Overlapping the Yukon and Northwest Territories, is the Inuvialuit Final Agreement/Western Arctic Claim, effective 1984.

In the Northwest Territories there the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, effective 1992; the Sahtu Dene and Metis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, effective 1994; the Déline - Sahtu Dene and Métis - Self-Government Agreement, effective 2016; and the Tlicho Agreement, effective 2005.

Throughout this report, CLCs (with or without SGA) will be referred to as 'Treaties' and standalone SGA and sectoral agreements will be referred as 'Agreements' unless otherwise specified.

Implementation of Treaties and Agreements

The Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, adopted in 2015, calls for a whole-of-government approach to implementation and provides the operational framework for management of the Crown's obligations. An accompanying Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation outlines Canada's intended whole-of-government approach to working with Indigenous signatories to support implementation and help promote reconciliation.

The whole-of-government approach is reflected in key roles and responsibilities for implementation, which span the federal government:Footnote 6

- The Department of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) is the lead for the Government of Canada for the negotiation of Treaties and Agreements, as well as subsequent coordination and implementation of activities that support full and honourable fulfillment of Canada's obligations and commitments. Within CIRNAC, the Treaties and Aboriginal Government (TAG) Sector is responsible for leading negotiations. The Implementation Sector (IS) is responsible for the implementation of Treaties and Agreements once finalized, including the negotiations of amendments and renewals, fiscal transfers and governance structures that vary from agreement to agreement. Each sector provides the other with input and support where appropriate.

- Tripartite Implementation Committees (sometimes known by an alternative name such as an Implementation Working Group) include representation from each signatory group and serve as a practical arrangement to jointly direct and oversee implementation. Committee responsibilities include, but are not limited to, providing a line of communication between forum members and senior-level decision-makers in each party, liaising with external stakeholders such as boards and committees, and identifying, resolving, or escalating issues or disputes as they arise during implementation.

- All federal Departments and Agencies are responsible for being aware of, understanding, and implementing Department/Agency-specific (and shared) obligations as required by Treaties and Agreements and as overseen by their leadership. They are also responsible for conducting an Assessment of Modern Treaty Implications when developing policy, plan, and program proposals for Cabinet. Individual Departments/Agencies may participate in implementation activities and governance structures, such as Implementation Committee meetings, as needed to ensure their obligations are fulfilled – for example, to discuss and resolve issues or disputes raised by Indigenous signatories.

- The Deputy Ministers Oversight Committee, chaired by the Deputy Minister of CIRNAC, provides executive oversight and direction to implementation of the Cabinet Directive and, by extension, Canada's roles and responsibilities to support a whole-of-government approach to implementation. The Modern Treaty Implementation Office (MTIO), situated within the IS, serves as the Secretariat for the Deputy Ministers' Oversight Committee and provides interdepartmental coordination and whole-of-government support on compliance, issues, disputes, and governance.

1.2 Program Profile

Management & Implementation Activities

The Implementation Branch (IB) is one of three branches within the IS. It is accompanied by the Consultation and Accommodation Unit and the Policy, Planning and Coordination branch, which houses the MTIO.

Figure 2 depicts the organizational structure of the IS, illustrating the separation between implementation (led by the IS) and negotiation (led by TAG).

Figure 2: Organizational Structure of Implementation Sector and Implementation Branch

Text alternative for Figure 2: Organizational Structure of Implementation Sector and Implementation Branch

Figure 2 shows the current organizational structure of the Implementation Sector and Implementation Branch, organized by hierarchy.

At the highest level is Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC).

At the next level, there is the Implementation Sector (IS) and Treaties and Aboriginal Government (TAG).

At the next level under Implementation Sector, there is Policy, Planning and Coordination (PPC), which houses the Modern Treaty Implementation Office (MTIO) and the Secretariat for Deputy Ministers Oversight Committee (DMOC). At this level, there is also the Implementation Branch (IB) and Consultation and Accommodation (CAU).

At the next and last level, there are the Treaty Management Directorates: Treaty Management East (Atlantic Provinces, Nunavut, Ontario, and Quebec); Treaty Management West (Northwest Territories, Prairie Provinces, Yukon); Treaty Management BC (British Columbia, Fiscal Policy, Collaborative Working Group Coordination); and Funding Services Unit (FSU) (Central agency reporting, budget management, advisory services, administration of Gs&Cs).

The IB administers the Management & Implementation (M&I) 'program', herein referred to as "M&I activities", in support of its objective to create and maintain ongoing partnerships and support the full and fair implementation of Treaties and Agreements and, by extension, reconciliation between Canada and Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 7 As shown in Figure 2, there are three Treaty Management Directorates within the IB – each a geographical unit led by a Director – and a dedicated Funding Services Unit responsible for central agency reporting, budget management, advisory services, and administration of all sector Grants and Contributions.

M&I activities undertaken by each Treaty Management Directorate, supported by the Funding Services Unit, include:

- Coordinating/implementing obligations under Treaties and Agreements;

- Managing intergovernmental relationships with Indigenous signatories (inclusive of representing Canada on tripartite Implementation Committees, engaging Indigenous signatories in negotiations/consultations);

- Working bilaterally to support other government departments and agencies, inclusive of supporting capacity building and facilitating dispute resolutions; and

- Where requested, supporting Indigenous communities in articulating their interests, participating in economic activities, and managing and developing land and resources.

Transformation

Significant organizational transformation was undertaken in recent years to enable innovative leadership and advance nation-to-nation and Crown-Inuit relationships, repeatedly affecting implementation roles and responsibilities. Notable changes included:

- The establishment of the Cabinet Directive in 2015, followed by the creation of the Deputy Ministers' Oversight Committee and the MTIO;

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's dissolution in August 2017 to create two new Departments, CIRNAC and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC);

- The establishment of the IS alongside the creation of CIRNAC to enhance focus on implementation, which involved relocating the IB from TAG to the IS, formally dividing responsibility and oversight for negotiation and implementation between two sectors each with their own Assistant Deputy Minister; and

- The establishment of the Funding Services Unit and Treaty Management BC within the IB as well as the relocation of the MTIO from the IB to Policy, Planning and Coordination over 2018-19 to 2020-21.

These changes occurred amidst an evolving policy landscapeFootnote 8 and the emergence of COVID-19, both of which further precipitated changes to M&I activities.

1.3 Expected Results

Indigenous Peoples, Canadians, and Indigenous and federal/provincial/territorial governments are expected to benefit through the implementation of Treaties and Agreements, supported by M&I activities; however, the primary beneficiaries are expected to be the citizens of Indigenous signatory groups.

Broadly, M&I activities are intended to: improve knowledge and understanding of Treaties and Agreements across the federal government to ensure that Canada's obligations are fulfilled; improve nation-to-nation, Crown-Inuit, and government-to-government relationships; and contribute in supporting Indigenous Peoples to advance their governance institutions and manage and control programs and services as they desire. Progress in each of these areas is ultimately expected to contribute in supporting self-determination by Indigenous Peoples and addressing socio-economic inequities. As such, M&I activities strongly align with the Rights and Self-determination core responsibility of CIRNAC's Departmental Results Framework and work towards achieving the Departmental Result: Indigenous Peoples and Northerners determine their political, economic, social, and cultural development (see Appendix A for the program logic model).

1.4 Program Resources

Indigenous Self-Governments are autonomous governments as set out in Modern Treaties and self-government agreements. Through the signing of these Agreements and Treaties, partners have moved out from under the Indian Act and are accountable primarily to their people and work to protect and preserve beneficiaries' rights, advocate for their interests, and implement their respective Treaties and Agreements. A fundamental principle of the Government's intergovernmental relationship with Self-Governing Indigenous Governments is that they are best-placed to deliver programs and services to their citizens. These include the delivery of programs and services to their citizens in relation to lands and resource management, heritage and culture, social services, health, capital and community infrastructure, economic development, and education. As such, they have expenditure responsibilities and obligations that are generally broader than those of First Nations under the Indian Act, or Inuit or Métis groups that are not self-governing.

Grants to Indigenous governments and organizations designated to receive claim settlement payments pursuant to Comprehensive Land Claim Settlement Acts are statutorily protected. As such, these transfer payments are treated similarly to Provincial/Territorial Government transfers, and limited reporting requirements apply.Footnote 9

Between April 2015 and March 2021, M&I transfer expenditures totalled $4.5 billion. Table 1 provides the breakdown of actual expenditures by fiscal year over this period.

| Category | Expenditures ($ Amounts by Fiscal Year, in Millions) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

| Operating Expenditures | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 |

| Grants & ContributionsFootnote 10 | 421.8 | 520.6 | 755.4 | 621.0 | 903.9 | 958.1 |

| Statutory Expenditures | 47.3 | 69.2 | 62.8 | 55.9 | 53.3 | 20.6 |

| Annual Total | 474.1 | 594.9 | 823.4 | 682.8 | 962.7 | 984.7 |

Grants and Contributions accounted for the majority of expenditures (92%), covering several program authorities, as shown in Table 2.

| Grants | Contributions |

|---|---|

|

|

2. Evaluation Description

2.1 Purpose and Scope

In accordance with the CIRNAC's Five-Year Evaluation Plan and in compliance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results, the purpose of this evaluation was to examine the M&I of Treaties and Agreements for the period between April 2015 and March 2021. As the program includes ongoing Grants and Contributions, the evaluation was further subject to Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation covered activities and outcomes specific to the IB's management and implementation of Agreements and Treaties, post 1975, that were negotiated in alignment with the Comprehensive Land Claims and Inherent Rights policies. Issues of relevance, design & delivery, effectiveness, and efficiency were addressed. While important, the activities and outcomes specific to Provincial/Territorial Government and other government departments implementation were out of scope of this evaluation.

This evaluation builds upon several recent reviews including the 2020 Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, 2016 Evaluation of the Impacts of Self-Government Agreements, and predecessors. Findings are intended to inform evidence-based decision-making for policy and program improvements and renewals in support of the program's unique role in advancing Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation relationships.

2.2 Methodology

The evaluation utilized a mixed-methods approach with multiple lines of inquiry to comprehensively address the identified issues and key evaluation questions. The Evaluation Matrix in Appendix B provides additional information. Lines of evidence included:

| Document Review | Performance Data Review |

Key Informant Interviews |

Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

A comprehensive review of grey literature and program files, including:

|

A review of performance data from sources, such as:

|

Semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted virtually or by written submission with 69 participants interviewed, representing the following groups:

|

Three case studies were undertaken to provide an in-depth investigation of best practices and emerging issues in relation to:

|

2.3 Limitations

| Limitations | Mitigation |

|---|---|

| 1. There were M&I activities that fell beyond the scope of the evaluation that were not fully explored or reflected in the findings and recommendations. | Strategies employed to mitigate limitations included:

|

| 2. The ability to understand structures and activities related to M&I and to distinguish activities of the IB from related activities of the MTIO or TAG were challenges for key informants. This may have limited their ability to share perspectives related to some M&I activities and introduced possible attribution challenges. | |

| 3. There was limited availability of program documents and data. This was likely due at least in part to the newness of both CIRNAC and the IS. For example, there was limited availability of some performance measurement data (e.g., the Modern Treaty Management Environment was not complete and up to date) and limited documentation of M&I roles and responsibilities, plans, and activity records to further extend, confirm, and contextualize findings. Some intended outcomes could also not be fully assessed because the data was held outside of the IB (e.g., by the MTIO or Indigenous governments) and was not available or provided. | |

| 4. There is potential for response bias given that the views and experiences of key informants who elected to voluntarily participate in the evaluation may have differed from those who did not – particularly if the value of participation was not clear for some given the opportunity cost. |

Overall conclusions and recommendations were developed on the collective basis of all findings to further enhance validity, reliability, and credibility, as well as utility.

3. Findings

The following sub-sections present overall findings and supporting evidence for the evaluation issues of relevance, design & delivery, and effectiveness.

3.1 Relevance

Finding 1. M&I activities align with the Government of Canada and Departmental priority of reconciliation. There is a continuing need to ensure full and honourable, whole-of-government implementation of Treaties and Agreements, which mark the beginning of a new relationship between Indigenous signatories and the Crown and support reconciliation.

Federal and departmental priorities include recognizing Indigenous rights, supporting self-determination, and advancing reconciliation, as stated in:

- Speeches from the Throne: Speeches from the Throne in 2020 and 2021 emphasized the federal government's commitment to reconciliation, inclusive of addressing systemic racism and inequities ('gaps') faced by Indigenous communities and implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Calls to Action, among others.

- Ministerial Mandate Letters: Letters state that "No relationship is [or remains] more important to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous Peoples", emphasizing that strengthening this relationship involves working to advance self-determination and reconciliation.Footnote 11

- Departmental Plans and Reports: Departmental materials routinely acknowledge a commitment to advancing self-determination and reconciliation.Footnote 12

In its Final Report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission defined reconciliation as an ongoing process of establishing and maintaining respectful relationships, inclusive of repairing damaged trust by making apologies, providing individual and collective reparations, and following through with concrete actions that demonstrate real societal change. Key informants across groups emphasized the alignment between M&I activities and Canada's stated priorities of reconciliation and improving relationships with Indigenous Peoples, characterizing the transfer of rights and land through Treaties and Agreements as the pinnacle of reconciliation. Similar sentiment was shared at the Canada Modern Treaty and Self-Governing First Nations Forum (2017), during which implementation of Treaties and Agreements was identified as one of the most important ways to define and establish respectful nation-to-nation relationships and advance self-determination.

There is an ongoing need to facilitate and support implementation of Treaties and Agreements to align with federal legislation, particularly Indigenous rights affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982), the Inherent Right Policy (1995), and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,Footnote 13 as well as to fulfill legal obligations and legislative requirements stemming from finalized Treaties and Agreements themselves. Treaties and Agreements create a distinct order of government within Canada's constitutional framework. Treaties and Agreements articulate the terms for new, living relationships between Canada and Indigenous signatories, and in doing so, support progress towards reconciliation to the extent that commitments are subsequently realized and upheld. CLCs (with or without a SGA component) are constitutionally protected, while standalone SGA are legislatively backed. Thus, there will be a continuing need for federal resources, leadership, structures, and processes to support full and honourable implementation of Treaties and Agreements as well as to develop and maintain the intended nation-to-nation, Crown-Inuit, and government-to-government relationships they set forth.

As previously described in Section 1.1, the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation and the Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation together call for a whole-of-government approach to managing the Crown's obligations and establishing long-term, effective intergovernmental relationships with Indigenous partners to support implementation. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) as well as recent CIRNAC materials also specify that reconciliation is supported by promoting new bilateral mechanisms to work more closely with Indigenous leaders, establishing a new fiscal relationship with Indigenous signatories, and ensuring federal capacity "to facilitate and implement new policies and relationships", supported by "specialized expertise" on implementation.

Key informants similarly noted the continuing need for dedicated resources and processes to support implementation across the federal government (inclusive of capacity building, dispute resolution, and oversight) and to develop and maintain corporate knowledge and relationships with Indigenous partners. They also highlighted the need for personnel with specialized implementation knowledge to navigate emerging issues (e.g., major projects with impacts on Treaty partners, passage of legislation such as Bill C-92), evolving contexts (e.g., new obligations being triggered or disputes arising), and the time-limited nature of some Implementation Committees.

M&I activities encompass management of intergovernmental relationships with Indigenous signatories, co-development of fiscal policy with Indigenous partners, administration of Fiscal Financial Agreements/Financial Transfer Agreements, and working bilaterally with other government departments around specific issues. In doing so, M&I activities respond well to the identified needs for federal coordination and expertise with respect to implementation of Agreements and Treaties.

Finding 2. Several M&I activities reflect Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation relationships. However, framing M&I as a 'program’ and funding Indigenous signatories through program authorities (Grants and Contributions) may not reflect a true Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation approach given associated requirements and oversight that constrain Indigenous signatories’ autonomy.

Various M&I activities incorporate Crown-Inuit and/or nation-to-nation approaches in the way that they provide opportunities and support for Indigenous partners to come together with Canada (represented by the IB and involving other government departments as needed) to engage in discussions and negotiations, develop and strengthen relationships, and share in decision-making (e.g., co-development of fiscal policy) and responsibility (e.g., for co-management board appointments). Examples include Implementation Committees, the CFP development process, and the COVID-19 Working Group. Input from key informants across groups also highlighted that mostly utilizing grants to fund Indigenous partners aligned with a Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation approach more so than the alternative program authority – Contribution Agreements – since grants allow comparatively greater flexibility and place fewer requirements and constraints on recipients.

Nonetheless, several key informants across groups expressed confusion or disagreement with the characterization of M&I activities as a 'program' because such framing minimized the breadth and significance of Canada's enduring commitments to Indigenous signatories. Instead, key informants likened the IB's role and associated M&I activities to Intergovernmental Affairs or Global Affairs, which was seen to better reflect the living relationships Treaties and Agreements signify as well as the intended Crown-Inuit and nation-to-nation approach. The Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation similarly emphasizes that establishing and maintaining intergovernmental relationships are vital to implementation.

The CFP development process provides a clear example of the need for alternative fiscal measures and redefined relationships: in addition to all 25 Self-Governing Indigenous Groups (SGIG) entering into parallel Fiscal Financing Agreement/Financial Transfer Agreement negotiations under the new CFP, demand for a similar, more collaborative approach among groups without SGA led to the creation of the M5 table for Treaty holders without self-government and an annex specific to education Sectoral Agreements. Canada's willingness to work with Indigenous partners in this novel manner underscores the evolving context of its relationship with Indigenous signatories, as do developments external to the IB, such as the establishment of tables and passage of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Key informants' responses also called into question the compatibility of using standard program authorities (Grants and Contributions) given the evolving nature of the relationship between Canada and Indigenous signatories, coupled with discrepancies in the treatment of SGIG versus other governments (e.g., Provincial/Territorial Government or foreign governments). In particular, Contribution Agreements were described as being at odds with the intended intergovernmental relationship in the instances they were used. For example, 'gaps'-closing funding for infrastructure development had reporting requirements to substantiate future internal funding requests, which was seen to be inconsistent with the spirit and intent of Treaties and Agreements and infringe on the autonomy of SGIGs. Modern Treaty and Self-Governments are accountable to their citizens, and not beholden to Indian Act program reporting and performance requirements. Data sovereignty needs to be recognized and considered in the context of whole of government M&I activities.

A comparison of funding arrangements and oversight associated with legislated fiscal transfers to SGIG under the M&I 'program' versus transfer payments to provinces under the Equalization Program was undertaken to explore whether (and if so, how) Canada's intergovernmental approach to each level of government differed. The comparison was informed by publicly available information on each program and key informant feedback. As summarized in Table 3, differences were observed in Parliamentary oversight of expenditures between the programs despite both involving federal transfer payments to another level of government on the basis of a federal legislative authority. No provincial reporting requirements were identified in relation to the Equalization Program, although some reporting requirements for SGIG were, as in the example of the CFP 'gaps'-closing initiative. This finding would seem to run contrary to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommendation that accountability requirements for Indigenous governments "not be more onerous" than those imposed upon provincial governments.

| Equalization Program | M&I Program |

|---|---|

|

|

Finally, key informants across groups flagged additional M&I terminology that they saw to be at odds with a respectful approach to improving Crown-Inuit, nation-to-nation, or government-to-government relationships. Concerns were raised over the term 'gaps', which reflects a limiting and deficit-based view and distances inequities from their cause (e.g., past and present structural racism and colonialism), as well as the term 'capacity', which can reflect biased western assessments and value judgments about the sufficiency of individual, group, or organizational knowledge, skills, and/or resources. Scoping the evaluation to M&I activities without fulsome consideration of implementation activities or performance of the federal government as a whole was also seen by some to not reflect the intended intergovernmental relationship.

3.2 Design and Delivery

Finding 3. There is a need for greater clarity around roles and responsibilities related to implementation, both within CIRNAC and across the federal government. The extent to which IB personnel can advocate on behalf of Indigenous partners within the federal system and support a coordinated, whole-of-government approach to implementation is limited as a result.

There were several organizational changes throughout the evaluation period that affected key structures, roles, and responsibilities related to implementation of Treaties and Agreements. These included the creation of CIRNAC, the IS, and the Funding Services Unit, among others. Despite changes, the IB retained responsibility for creating and maintaining ongoing partnerships to support implementation of Treaties and Agreements and for working bilaterally with other government departments on implementation issues. There was also increased attention and emphasis on implementation following the 2015 federal election.

Particularly due to organizational changes, key informants identified several roles and responsibilities that required or would benefit from additional clarity. For instance, it was observed that the relocation of the MTIO to Policy, Planning and Coordination Branch created a continuing need to establish structures and processes within the IB to manage and respond to horizontal implementation issues. Relatedly, key informants identified an opportunity to better clarify and coordinate roles and responsibilities between the IB and the MTIO to ensure that the MTIO is equipped with greater understanding of the current implementation context when engaging with Indigenous partners.

Key informants also saw room to clarify roles and responsibilities for training and implementation of obligations between CIRNAC and other government departments, inclusive of clarifying which department is the lead for shared or whole-of-government obligations. For instance, some key informants raised concerns about other government departments representatives' limited knowledge of departmental roles and responsibilities or tendency to defer to CIRNAC in circumstances of shared obligations. In addition, there were reports that some other government departments are unsure of their departmental requirements or obligations in certain circumstances and would welcome additional guidance and information from the IB through additional documentation, policies, or notifications, such as about annual reporting requirements or when obligations are triggered.

Table 4 identifies implementation roles and responsibilities across departments, across CIRNAC (particularly TAG and the IS), and within the IS that may benefit from clarification.

| Across departments | Across CIRNAC | Within IS and IB |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

As illustrated by these examples, existing processes and structures do not make implementation roles and responsibilities sufficiently clear across the federal government. For example, there is little documentation of IB roles and responsibilities (e.g., no CIRNAC intranet page, Funding Services Unit inherited little documentation alongside new responsibilities, such as performance reporting), nor are there requirements for other government departments to consult the IB or partners while conducting an Assessment of Modern Treaty Implications, despite concerns flagged in the 2020 Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation. Instead, public servants rely on existing knowledge, relationships with IB personnel, and 'learning on the job' to develop their understanding of the IB's function. Not only does this present a risk of lost institutional knowledge when there is turnover in key roles, it also limits other government departments'ability to identify opportunities for coordination and for the IB to provide (or other government departments to access) "Treaty expertise" or support.

Some key informants reported that their ability to fulfill departmental obligations is hindered by resource constraints resulting from limited clarity of their department's roles and responsibilities in relation to implementation. While some attributed the lack of clarity to having an incomplete understanding of what the Crown committed to during the negotiation phase for Treaties and Agreements, others stressed ongoing challenges due to implementation roles and responsibilities not being clearly stated in foundational material such as Ministerial mandate letters. IB documentation also identifies a need for the IS to engage other government departments, supported by TAG's Fiscal Policy Branch, to strengthen forecasting for other government departments funding requirements to implement obligations, further highlighting the need to enhance clarity of roles and responsibilities to enable fulsome implementation.

Several key informants expressed that there was a limited extent to which Indigenous partners experienced a whole-of-government response to implementation, inclusive of difficulty gaining traction with some other government departments. As a result, a need was identified for processes and structures to support greater coordination and awareness of implementation roles and responsibilities across the federal government. Several key informants across groups also called for mechanisms to enhance accountability given the challenges faced by Indigenous partners when attempting to engage other government departments on implementation matters. Previous evaluations similarly identified a need to clarify implementation-related roles and responsibilities within the Department and across the federal government as well as to document processes and formalize coordination across departments, especially around cross-cutting issues. These included the 2020 Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation and the 2009 Impact Evaluation of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements.

There is some recent evidence of attempts to enhance clarity in program documentation. For example, the Funding Services Unit developed a Directive on annual adjustors and an overview of the respective roles and responsibilities of TAG versus the IB in relation to resource management. Nonetheless, many of the challenges or limitations regarding clarity of implementation roles and responsibilities had not yet been addressed as of the writing of this report, suggesting a need for continued efforts in this area.

Finding 4. Stemming from an evolving understanding of what implementation requires and the relatively recent creation of CIRNAC and the IS, comprehensive mechanisms to fully and accurately assess IB resource requirements against defined roles and strategies and a fluctuating workload (e.g., as new Agreements are finalized and obligations are triggered) have not yet been established.

In line with the Statement of Principles on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation's recognition that "Modern Treaty implementation is an ongoing process", key informants across groups described how there has been an evolving understanding of the requirements and activities needed to implement Treaties and Agreements. For example, experiences over the evaluation period underscored to key informants that:

- Treaties and Agreements represent much more than the end of negotiations between the Crown and Indigenous Peoples; they articulate the rights and benefits of each party and mark the beginning of a new relationship;

- Developing and maintaining relationships requires sufficient, ongoing, and coordinated structures and processes that can respond to implementation issues and Indigenous partners' needs and priorities as they arise; and,

- Other government departments may not have the understanding or the structures and processes required to readily adapt to the new context and relationship that a Treaty or Agreement presents. For example, in the absence of established alternatives, other government departments may be reliant on Contribution Agreements to fund Indigenous partners.

The evolving Treaty and Agreement landscape has affected the volume and predictability of the IB's workload, as has organizational change. Key informants across groups acknowledged that the IB's resources are constrained given the extent of new, continuing, and upcoming demands related to M&I activities, which has direct implications for the IB's ability to develop and maintain relationships with Indigenous partners and support implementation in a timely, coordinated manner. The scope of activities that partners undertake to implement their Treaties and Agreements have grown significantly, as intergovernmental relations, management and stewardship of lands and resources, consultation processes, and co-developing policy with Canada all involve significant effort by partners.

There were notable changes over the evaluation period in the way that Canada, represented by the IB, works with Indigenous partners to implement Treaties and Agreements. New developments included establishment of the CFP development process and COVID-19 Working Group, both of which provide greater opportunity, support, and structure for collaboration and co-development between Canada and Indigenous partners in priority areas, such as redefining fiscal relationships and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Each of these emerging mechanisms will require ongoing resources and leadership from the IB.

Further, program documents indicate that the IB holds several significant implementation responsibilities that were not initially anticipated and should be a consideration given the relative risk to sound departmental financial management. These include responsibilities for Section 35 forecasting, providing high-demand support to other government departments, supporting and leading central agency submissions, and undertaking the Modern Treaty Management Environment data validation and collection. Key informants as well as program documents and data also indicate that the IB's workload has been increasing as additional Agreements are finalized and new obligations are triggered. As an example, Table 5 shows the number of agreements, amendments, and funding requests processed by the Funding Services Unit over the evaluation period to illustrate the increasing amount of work undertaken by the IB.

| No of Grants and Contributions Transactions | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreements | 106 | 112 | 101 | 140 | 459 |

| Amendments | 37 | 24 | 88 | 133 | 282 |

| Notice of Budget Adjustment | 13 | 7 | 87 | 46 | 153 |

| Funding Requests | 0 | 0 | 8 | 32 | 40 |

| Total | 156 | 143 | 284 | 351 | 934 |

As identified, the IB is currently responsible for the implementation of 32 concluded Treaties and Agreements under which CIRNAC has obligations. As of October 2020, 151 Indigenous groups were engaged in 155 discussions, negotiations, and consultations with objectives to reach Agreements with the Crown.

While the exact impact of upcoming Treaties and Agreements on IB workload remains unclear, it is likely that the IB will be responsible for supporting implementation of upcoming Agreements in the same manner as those previously concluded. For instance, it is anticipated that the IB will maintain overall responsibility for managing relationships with Indigenous signatories as well as coordinating and implementing obligations, including agreements signed at Recognition of Rights and Self-Determination tables. Not only could new Agreements therefore increase the IB's workload significantly in coming years, but they may also introduce new and more complex implementation considerations with unknown impacts on IB activities. For example, the IB has found that the 12 agreements signed at Recognition of Rights and Self-Determination tables have had more complex implementation requirements, further stretching the IB's resources and ability to strategically plan.

Some key informants reported recent attempts to clarify the IB's resource needs given current workload and constraints faced – for example, one unit assessed time allocated to documented responsibilities versus other activities required to support implementation. Nonetheless, feedback suggests that the IB resource requirements have not yet been comprehensively nor systematically assessed against defined roles, plans, and strategies for implementation of Treaties and Agreements (concluded or upcoming). There also appears to be limited performance data on core program activities (e.g., liaising, building relationships) that could support an assessment of resourcing sufficiency if available. Taken together, these data suggest a clear, imminent, and unmet need for mechanisms to fully and accurately assess workload and resource requirements so that the IB is adequately equipped to fulfill its roles and responsibilities for implementation.

Finding 5. Indigenous signatories are insufficiently resourced to implement their obligations and respond to emerging implementation issues and opportunities. Recent efforts such as the CFP development process have provided enhanced funding for governance to support Indigenous partners to address underlying inequities but are not sufficient on their own.

Key informants across groups agreed that there is an ongoing need to fund Indigenous partners to implement Treaties and Agreements and be meaningfully involved in fiscal policy development and decision-making. Sufficient funding is also needed for SGIG to self-govern (e.g., for ongoing management of lands, programs, and services, etc.) and address underlying socioeconomic inequities that fall beyond the scope of the Treaties and Agreements signed. However, key informants recognized that past and current resourcing have been insufficient for undertaking all of the above.

Factors contributing to insufficient resourcing levels for Indigenous partners include:

- Fiscal Financing Agreements/Financial Transfer Agreements providing insufficient funding for implementation, such as no core governance funding for Treaties with no SGA component and not accounting for added expenses in remote locations;

- Underlying inequities or 'deficits' due to past policy and underinvestment, resulting in persistent challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, among others; and

- Continued funding limitations in areas of priority for Indigenous partners, such as special education and post-secondary education, language revitalization, and housing.

The CFP development process was initiated in recognition of the need to develop a new fiscal relationship between Canada and SGIG to address unmet needs and persistent inequities such as those described above and to redefine the fiscal relationship between Canada and Indigenous partners moving forward. As articulated in the CFP Steering Committee meeting notes, "The whole fiscal policy is about reconciliation and supporting [Indigenous governments]. Reconciliation is about putting things right and dealing with the real impacts of legacy policy choices over the years". Additional documentation and input from CIRNAC's officials and Indigenous partners similarly emphasize that initial goals of the CFP development process included providing viable funding for SGIG to self-govern as well as to address persistent socio-economic inequities.

The co-developed CFP outlines processes for collaboratively identifying and defining areas in need of increased investment (commonly referred to as 'gaps'-closing funding) and developing funding methodologies. Key informants across groups also identified a need for fiscal policy and associated processes to recognize and respond to different considerations and contexts for different Indigenous partners to ensure that clauses in specific Agreements are followed and that funding methodologies take into consideration unique circumstances (e.g., First Nations that have non-members living on their lands). Similar goals to define and address unmet resource needs for signatories without SGA underpinned the subsequent establishment of the M5 table and education annex.

The CFP development process and related offshoots reflect a shared understanding that Indigenous partners require additional resources and provide a new mechanism for iteratively and collaboratively addressing unmet needs. While these emerging processes have so far increased funding in some areas, such as advancing governance structures and capabilities (see Finding 10 for more), there is agreement that additional resources are needed. For instance, insufficient human and financial resources continue to present implementation challenges for some Indigenous governments. As a result, staff may be too few and stretched too thin to participate in all the implementation activities they may like to, with some relying on continued support from external consultants as a result. Hiring was also flagged as a key challenge for some Indigenous governments due to factors such as limited availability of personnel or ability to offer competitive salaries given available resources.

Several phases of the CFP development process are ongoing or upcoming, with plans to shape policy development and address SGIG funding needs in additional areas. Internal program documents indicate that these areas include: treaty, land, and resource management (in a coordinated effort with five Treaty signatories from the Northwest Territories and Quebec); culture, language, and heritage; infrastructure and housing; and annual funding adjusters. Key informant feedback indicates that continued work to address resource needs through the M5 table and education annex is also planned.

Finding 6. There is a need to enhance the relevance and reliability of performance data to support decision-making. For instance, some performance data was unavailable, incomplete, and/or untested. The M&I logic model and corresponding performance measurement data do not reflect the nature of outcomes for intergovernmental relationships.

There was a general perception among key informants that the performance measurement system has not been generating valid and reliable performance data, although there have been recent actions undertaken to address challenges, including development of a new Performance Information Profile in 2021. The review of performance data also revealed that some planned metrics were not available or up to date. For example, education data was not provided by the program and, as shown in Figure 3, most obligations had not yet been accepted and updated in the Modern Treaty Management Environment by the respective federal government department (of 8,612 total obligations).

Figure 3: Status of Canada's Obligations in the Modern Treaty Management Environment, October 2021

Text alternative for Figure 3: Status of Canada's Obligations in the Modern Treaty Management Environment, October 2021

Figure 3 shows a pie graph comparing the status of Canada’s obligations in the Modern Treaty Management Environment in October 2021.

84% of obligations are pending.

12% of obligations are accepted.

5% of obligations are rejected.

Some new performance measures (e.g., the number of times advice was provided to federal officials regarding the Assessment of Modern Treaty Implications) were also untested as of the writing of this report, so their utility is not yet known.

Challenges measuring the performance of M&I activities and their contribution to intended outcomes have been long acknowledged. For instance, the Inuvialuit Final Agreement of the October 2007 Report of the Auditor General of Canada noted that Indian and Northern Affairs Canada had not developed performance indicators or other means to "ensure measurement of progress toward achievement of the principles that the Agreement embodies". Recent evaluations including the 2009 Impact Evaluation of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements, 2016 Evaluation of the Impact of Self-Government Agreements, and 2020 Evaluation of the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation also identified collaborative development of performance measures as a priority, underscoring that adequate performance measures had yet to be developed.

Based on the input received from key informants, a central tension appears to be at the heart of the IB's performance measurement challenge. On one hand, there is demand to assess both the performance of M&I activities and the federal government's overall implementation of Treaties and Agreements and fulfillment of obligations as a whole. On the other, there is also a need for the IB and IS leadership to systematically analyze the delivery and performance of the M&I activities over which they have direct influence and control. This is challenging to do in practice because of the interconnectedness of M&I activities undertaken by the IB and related activities undertaken by other branches/sectors within CIRNAC and other government departments to support implementation. Training on Treaties and Agreements provides a good example: IB, MTIO, other government departments, and the Canada School of Public Service each undertake and contribute to training on Treaties and Agreements, and the action of one or more parties can affect actual or perceived performance or effectiveness of the other(s). Shared responsibilities may also present data access challenges depending on who collects, stores, and has access to data. The same applies to intended outcomes, which may depend on multiple inputs and actors – including Indigenous partners.

Assessing performance of M&I activities is further complicated by the incomplete, evolving, and largely undocumented understanding of implementation roles and responsibilities across the federal government, including within the IB (as discussed in findings 3 and 4). This presents a practical challenge for performance measurement: it is difficult to measure the performance and contribution of select activities to intended outcomes if those activities are not clearly and consistently defined.

The logic model for M&I activities (see Appendix A: M&I Logic Model) is a practical tool to support 'program' planning, implementation, and assessment by providing a visual outline of the linkages between inputs, M&I activities, and intended outcomes. The logic model is not intended to depict the theory of change for whole-of-government implementation of Treaties and Agreements. Nonetheless, documents and key informant feedback indicate that the M&I logic model and corresponding performance data reflect that the IB can only influence some of the outcomes, and a whole-of-government approach, is required to achieve all of the outcomes. These include training (as described above) and providing advice on Assessment of Modern Treaty Implications, which is now a responsibility of the MTIO. The IB also has shared or indirect influence on some expected outcomes, such as those related to Indigenous Peoples advancing their governance institutions and determining their political, economic, social, and cultural development. These observations about inconsistencies between the M&I logic model and the IB's locus of control appear consistent with challenges raised by key informants.

To enhance performance measurement, key informants across groups identified several measures that would be appropriate, useful indicators of progress and/or success for M&I activities but that are not currently measured. Preferred measures largely centered on the effectiveness of – and Indigenous partners' satisfaction with – relationships with the IB, CIRNAC, other government departments, and the federal government as a whole, as well as overall progress on implementation of obligations. Additional indicators identified by some key informants included Indigenous partners' perceptions of the sufficiency of support they receive from Canada to undertake implementation and the extent of progress made by the federal government in priority areas identified by individual Treaty and Agreement signatories, such as annual goals or priorities shared at Implementation Committee meetings. Some public servants added that avoidance of litigation would also be a useful indicator of whether implementation activities were reducing disputes or providing effective mechanisms to resolve disputes out of court. Continued interest in measuring socioeconomic well-being and progress were also expressed, echoing a recommendation from the 2016 Evaluation of the Impact of Self-Government Agreements.