Evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process FY2013-14 to FY2019-20

Prepared by: Evaluation Branch

November 2022

PDF Version (70 pages, 1,080 KB)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

- 3. Relevance: Continued Need

- 3.1 Relevance: Alignment with Federal Priorities

- 3.2 Relevance: Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 3.3 Relevance: Alignment with CIRNAC Mandate and Priorities

- 3.4 Relevance: Alignment with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Calls to Action

- 3.5 Design and Delivery: Impartiality and Fairness

- 3.6 Design and Delivery: Accountability and Transparency

- 3.7 Design and Delivery: Rapid Processing

- 3.8 Design and Delivery: Access to Mediation

- 3.9 Design and Delivery: Program Delivery and Governance

- 3.10 Design and Delivery: Capacity and Resources

- 3.11 Design and Delivery: Audit and Evaluation Recommendations

- 3.12 Design and Delivery: Gender-based Analysis Plus

- 3.13 Design and Delivery: Performance Measurement

- 3.14 Performance: Achievement of Outcomes

- 4. Efficiency and Economy

- 5. Conclusions and Recommendations

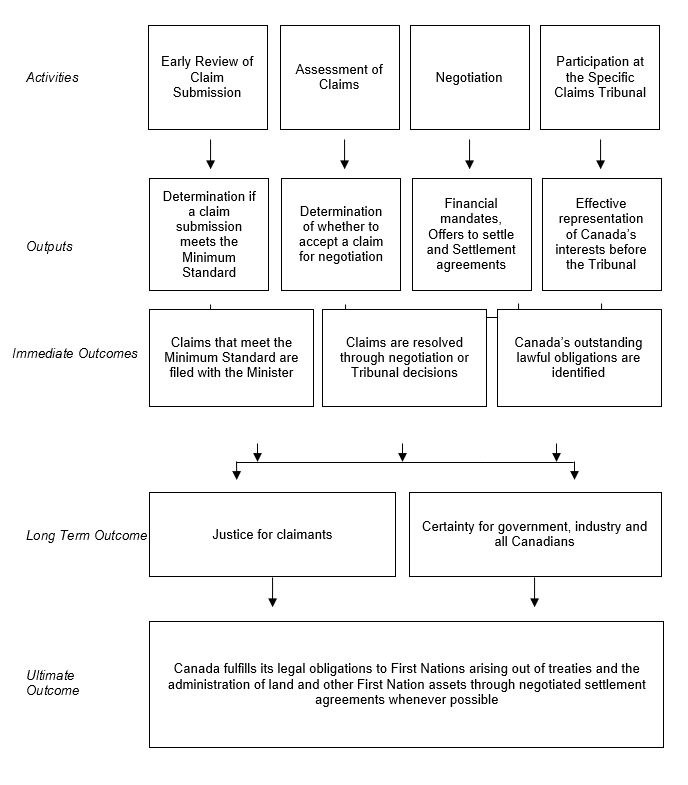

- Appendix A - Logic Model

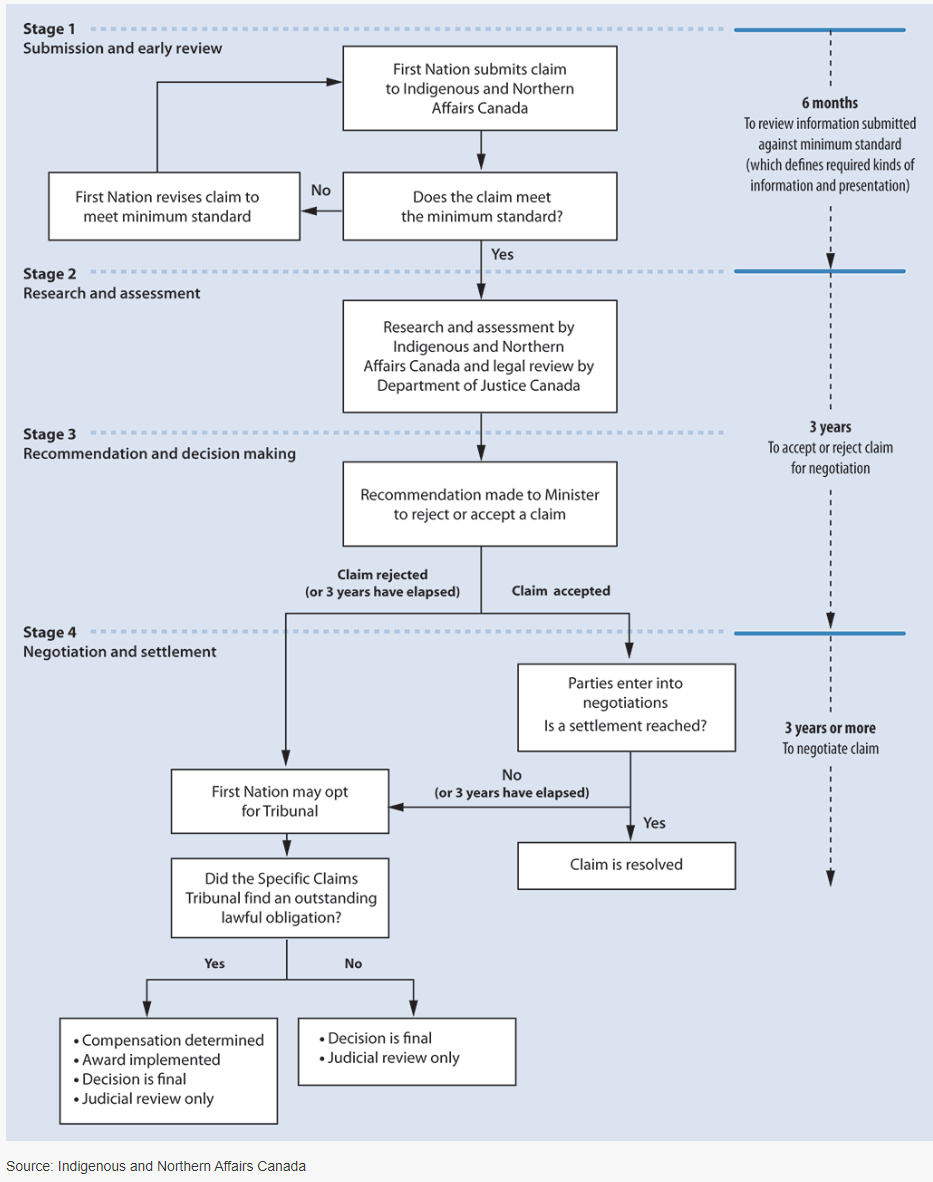

- Appendix B - The Specific Claims Process

Acronyms

- AFN

- Assembly of First Nations

- CIRNAC

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- DOJ

- Department of Justice

- GBA Plus

- Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- INAC

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- JTWG

- Joint Technical Working Group on Specific Claims

- OAG

- Office of the Auditor General

- SCB

- Specific Claims Branch

- SCP

- Specific Claims Process

- TRC

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

- UNDRIP

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Executive Summary

Overview

The Evaluation Branch of the Audit and Evaluation Sector of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) conducted an evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process (SCP). The evaluation was undertaken as outlined in CIRNAC’s Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2019-2020 to 2023-2024 and in compliance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation focuses on relevance, design and delivery and effectiveness. The evaluation covered the period of April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2020.

The program is delivered by the Specific Claims Branch (SCB), Resolution and Partnership Sector, of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC).

Specific claims are grievances that First Nations have against the Government of Canada for failing to discharge its lawful obligations with respect to historic pre-1975 treaties and the management of First Nation lands, monies and other assets. The resolution of specific claims advances reconciliation and supports nation building and self-governance, where settlement funds can be used by First Nations to advance their priorities and community development. Specific claims are separate and distinct from comprehensive land claims or modern treaties.

In 2016, the Office of the Auditor General conducted a performance audit, which reported on whether the department adequately managed the resolution of First Nations specific claims. The audit noted the lengthy assessment and negotiation processes are impediments to achieving restitution for past wrongs.

An Evaluation Working Group provided guidance on the evaluation process and to ensure diverse perspectives were reflected in the evaluation. This included representatives from the evaluation team, SCB program representatives, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), and the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and others.

The evaluation methods included a review of program documents, a review of performance and financial data from the specific claims database, 51 key Informant interviews (with federal government representatives, Indigenous governments, Indigenous Representative Organizations and Claims Research Units, and other Indigenous representatives); and eight case studies of specific claims in various stages of the process, which included a review of core claim documents and 20 key informant interviews as part of case studies.

The case studies considered the experiences of First Nations at various key stages in the process, examined the role of the SCB and identified key challenges at various stages of the process.

Recommendations to support improvements in CIRNAC’s approach to working with Indigenous partners and managing and implementing Treaties and Agreements follow.

Relevance

The evaluation found that the need to resolve specific claims is a priority for First Nations and necessary for Canada to honour its obligations to right these past wrongs. As the Government of Canada is accountable for fulfilling statutory and fiduciary obligations to First Nations as well as upholding the honour of the CrownFootnote 1, it is expected that the need to resolve specific claims will continue on a long-term basis.

This continued need will drive the requirement for an impartial, fair, transparent and efficient policy and process for resolving specific claims through negotiated settlements and other alternatives to the courts.

In the absence of the specific claims policy and process, claims litigation would be the primary pathway to resolution, which is not the preferred approach as it is more costly and time consuming, eroding relationships with First Nations, and ultimately reconciliation between Canada and First Nations.

There are continued expectations that the specific claims policy and process will be consistent with, aligned to, and supportive of the priorities and plans of First Nations, Canada's obligations to right past wrongs, and the federal government's priorities for renewed, nation-to-nation, government-to-government relationships with First Nations, reconciliation, commitments to implement the TRC Calls to Action, and to be in compliance with United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Despite incremental federal reforms, FNs, their representatives, oversight bodies and other observers have made the same criticisms that the SCP is not meeting needs and expectations and that transformational change is required to address these longstanding issues.

Design and Delivery

In terms of impartiality and fairness, and accountability and transparency, respondents pointed to UNDRIP Article 27 calling for a "fair, independent, impartial, open and transparent process" to be implemented in conjunction with the concerned Indigenous peopleFootnote 2. Introduction of the Tribunal and incremental federal reforms has improved impartiality and fairness of the existing process, however it remains out of compliance with Article 27.

The resourcing of the SCP appears to have hindered the ability of First Nations to develop and submit claims, and participate in negotiations, and the SCB’s ability to meet expectations, such as legislated timeline targets. For First Nations, adequacy of resourcing (including research funding outside the purview of the SCB) is the primary driver for prospective claims entering the claims resolution process.

An increase in the volume of claims combined with targets for initial review, and assessment and negotiation, have been beyond the current resources and staffing allocations, resulting in lengthy periods to resolve claims and failure to meet legislated timelines. For the SCB, according to interviews with program representatives, staff have been faced with excessive workloads, resulting in high rates of absenteeism and attrition.

Greater collaboration, communication and information sharing has led to improvements in accountability and transparency, though a continued focus on improving these areas is still needed.

Effectiveness

There are challenges with the program framework, including misalignment of indicators with outcomes and the reliance on contextual indicators. Both internal and external respondents recognized many of these and other issues (i.e., unrealistic targets) are deficiencies with the program performance framework. SCB officials indicated that some of these were already being addressed through an internal review process.

With respect to monitoring, the program uses a simple output volume calculation to monitor performance. This output volume approach looks at all claims in the SCB portfolio in a particular year, and describes how many are at various stages in their life cycle, regardless of when they were submitted to the Minister. Given that the federal government plans and budgets on a fiscal year basis, that claims are managed through different lifecycle stages (with important, including legislated, performance standards), and many of the program indicators are qualified "by year and trend," the evaluation team expected that the program would use cohort analysis to help provide insight into the performance of the claims process. Instead, the program relies on simple volume calculations, which does not fully account for the lifecycle of claim.

From a narrow operational sense (activities and immediate outcomes), program performance has been good, largely attributable to the expertise and deep dedication of staff. Performance on meeting the legislated three-year timeframe for determining whether claims will be accepted for negotiation fell slightly short of expectations. However, the last three years demonstrated a trending significant improvement and the target was met.

From a broader perspective (intermediate and ultimate outcomes), the program has not performed well. With respect to advancing reconciliation with First Nations, respondents generally agreed that the SCP has the potential to advance reconciliation however, its current design particularly as it relates to impartiality, fairness and transparency are major impediments.

Efficiency and Economy

The program has continually explored different ways to increase efficiencies (e.g., joint research, bundling claims, global settlements and scaling of these best practices) and strived to ensure a positive experience for First Nations during the claims process, and there have been pockets of success.

First Nation respondents agreed that negotiated resolutions are the most cost-effective as well as their preferred means to resolve specific claims within the Specific Claims Policy, and suggested that greater efficiencies could be realized through more collaboration (e.g., joint research) and consistency in the approach to different classes of claims.

Capacity and resource constraints have impacted the SCB's ability to meet expectations and First Nation calls for accelerated resolution, and hindered the ability of First Nations to participate in the specific claims process on an equal footing with Canada.

Recommendations

The findings and conclusions from this evaluation have led to the following recommendations:

It is recommended that CIRNAC:

- Co-develop with First Nations partners a modern and transformative specific claims policy and process, that:

- Better aligns to Government of Canada and Departmental mandates and priorities and reflects UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action, including principles of and upholding the honour of the Crown.

- Establishes options for implementation, and a realistic and sufficiently resourced implementation plan, that can lead to more fairness, impartiality, transparency, independence and collaboration in the claims process.

- Ensures that Indigenous customs, rules, and legal systems are systemically incorporated into the specific claims policy and process.

- In cooperation with First Nations partners, continue its current improvement initiatives related to delivery, effectiveness and efficiency of the program, including:

- Communications - improving the clarity and opportunities for transfer of communication from SCB to First Nations; and, within the department between the directorates with the SCB and other areas that interface with the SCB (Pre-research Negotiations support branch in Treaties and Aboriginal Government and regions (ISC)).

- Performance Measurement – improving the data collection approach with more accurate and meaningful indicators and articulation of longer term outcomes, in consultation with First Nations.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process

1. Management Response

The Specific Claims Branch (SCB), Resolutions and Partnership Sector, acknowledges the findings of the report on the "Evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process FY2013-14 to FY2019-20".

The evaluation comes at an important time for the Specific Claims Program. Following the 2016 release of the statutorily mandated review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act and the Report of the Auditor General of Canada, the Specific Claims Program has made notable progress in working collaboratively with First Nations to accelerate the resolution of claims, while also working with First Nation partners to identify policy reform options for further improvement of the Program.

Since 2016, the Specific Claims Program has adopted approaches involving more collaboration and innovation with First Nation partners that are consistent with the Government’s overall commitment to improving the relationship with Indigenous peoples. By working more closely and collaboratively with First Nation partners, and seeking opportunities to bundle claims or mandates and to accelerate the resolution of claims, the Program settled more claims over the last three years than ever before. 117 claims were resolved during that period, or an average of 39 per year, compared to averages per year below 20, sometimes well below this number, in previous years. Furthermore, the average rate of acceptance of claims for negotiation has been about 90% in the last three years compared to about 60% or less in previous years, reflecting efforts to make the process less adversarial and to avoid unnecessary litigation of claims.

In addition to adopting on-going operational improvements to streamline the process and improve relationships with First Nation partners in negotiations, in 2016 a Joint Technical Working Group (JTWG) was established with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and other First Nation partners to identify practical measures to improve the specific claims process. The AFN led a national policy reform engagement exercise with First Nations during the fall of 2019. This engagement resulted in updated direction from AFN Chiefs in Assembly to contemplate an independent reformed resolution process for the settlement of specific claims.

In this context, the Specific Claims Program brought forward in 2022 a first stage of policy reform. A co-development process with the AFN and other First Nation partners was launched in November 2022 to reform the specific claims process, including the establishment of a Center for the resolution of specific claims as an independent body to administer and oversee key aspects of the process. Following the 2007 Justice at Last policy framework, we believe this policy reform process, which will be co-developed with First Nation partners, will likely determine the program’s strategic direction for the next decade or more. We therefore see the Evaluation Report’s importance not only in critically assessing how the Program evolved between 2013-14 and 2019-20, but also providing insight into how stakeholders might weigh our policy reform options going forward. In this context, we will consider the reference information and analysis that grounded the Evaluation’s recommendations to consider how its recommendations can be factored into policy and program reforms.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

1. Co-develop with First Nations partners a modern and transformative specific claims policy and process, that:

|

First Nations have called for changes to the way specific claims are handled by the federal government. CIRNAC is working closely with the AFN and other First Nations partners to find fair and practical ways to improve the specific claims process through an ambitious specific claims reform plan CIRNAC and the AFN formally launched a co-development exercise to develop a proposal for an independent centre for the resolution of specific claims in November 2022. CIRNAC is expected to bring forward a reform proposal based on this co-development exercise in 2024. The specific claims reform initiative will be looking to set up a reformed resolution process and further operational improvements. Key milestones range from the repeal of the Order in Council limiting the Minister’s authority to sign settlement agreements and an increase in the Minister’s mandate approval authority (completed in October 2022) to the approval of a proposal for the implementation of a centre for the resolution of specific claims targeted to be brought forward in 2024. The principles of UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action guide the design of this reform, which is based on a co-development approach to policy development. With respect to the integration of Indigenous legal systems into the specific claims resolution process, the Department does not currently have the expertise required to fully evaluate the potential implications of this proposal. It is anticipated that an Advisory Committee on Indigenous Laws would be established as part of the reform initiative to assist the federal government and First Nations partners by advising on the role Indigenous legal traditions could have in the process. |

Director General, Specific Claims Branch | Start Date: Ongoing |

| Completion Date: 2025-2026 | |||

2. In cooperation with First Nations partners, continue its current improvement initiatives related to delivery, effectiveness and efficiency of the program, including:

|

SCB has introduced measures to improve the intake and processing of claims submitted by First Nations. This includes the assessing of re-submitted claims and undertaking joint research initiatives to support the parties in coming to a common understanding of a claim. SCB is now more proactive throughout the assessment process to communicate with First Nations in order to ensure that any gaps in information do not prevent the assessment of a claim in a timely fashion. SCB has continued to improve clarity and opportunities for communication with First Nations by developing guidance for negotiators for explaining Canada’s positions clearly during the resolution process. In addition, the use of mediation where warranted is improving communication and information sharing. SCB directorates work closely together during the assessment and negotiation processes and SCB collaborates with other sectors such as Treaties and Aboriginal Government in addressing cross-cutting issues. SCB maintains ongoing communications with the Department of Justice which works closely with SCB at every stage of the assessment and resolution process and with other government departments such as Indigenous Services Canada as needed. In 2021-2022, SCB changed the main departmental result indicator for the program to better reflect the number of past injustices resolved by the program. Working with the Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Officer, as well as the Central Agencies, SCB will update its approach to performance measurement in the context of the reforms to the specific claims process that are being co-developed with the Assembly of First Nations and other First Nation partners. While the focus over the coming years will be on the reform of the process through the establishment of a specific claims resolution centre, SCB will also continue to implement operational improvements to the current process, and to work with the CIRNAC-AFN Joint Technical Working Group to identify issues requiring attention. It is anticipated that through these on-going improvements SCB will be able to increase its target for claims settled per year from the current 33 to 50 by 2025-26. |

Director General, Specific Claims Branch | Start Date: Ongoing |

| Completion Date: Within 3 years |

1. Introduction

1.1 Evaluation Purpose

In the Government of Canada, evaluation is the systematic and neutral collection and analysis of evidence to judge merit, worth or value. Evaluation informs decision making, improvements, innovation and accountability. Evaluations typically focus on programs, policies and generally employ social science research methods.

An evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process was required in accordance with Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act which stipulates that departments conduct a review every five years of the relevance and effectiveness of each ongoing program for which they are responsible. The Treasury Board of Canada’s Policy on Results (2016) defines such a review as an evaluation, and requires each department to develop and publish an annual five-year departmental evaluation plan. The evaluation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process (also referred to herein as "the program" or the SCP) was conducted as outlined in CIRNAC’s Five-Year Evaluation Plan 2019–2020 to 2023–2024.

An evaluation of the Specific Claims Process (SCP) was previously completed in 2013–2014 following an audit of department support to the SCP undertaken by the department’s Audit and Assurance Services Branch in 2012. In 2016, the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) conducted a performance audit, which reported on whether the department adequately managed the resolution of First Nations specific claims. The Office of the Auditor General Report, results of the evaluation (2014) and concerns of First Nations consistently noted that lengthy assessment and negotiation processes are impediments to achieving restitution for past wrongsFootnote 3.

The Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement Process was evaluated in FY2020-21 to assess the relevance, design and delivery, performance and efficiency of the program for the period of April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2020. This program is delivered by the Specific Claims Branch (SCB), Resolution and Partnership Sector, of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). The evaluation was initiated and conducted by the Evaluation Branch of CIRNAC.

1.2 Program Context

Specific claims are grievances that First Nations have against the Government of Canada for failing to discharge its lawful obligations with respect to historic pre-1975 treaties and the management of First Nation lands, monies and other assets. For example, a specific claim could involve the failure to provide enough reserve land as promised in a treaty or the improper handling of First Nation money by the federal government in the pastFootnote 4.

Specific claims are separate and distinct from comprehensive land claims or modern treaties.

The Government of Canada works with First Nations to resolve outstanding specific claims through negotiated settlements. The specific claims process is voluntary for First Nations and provides a way to resolve disputes outside of the court system. The negotiated settlements honour treaty and other legal obligationsFootnote 5.

The resolution of specific claims advances reconciliation and supports nation building and self-governance, where settlement funds can be used by First Nations to advance their priorities and community development.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, some First Nations sought redress from Canada; however, from 1927 to 1951, the Indian Act prohibited the use of band trust funds to sue the federal government. Claims that Canada had not fulfilled its lawful obligations to First Nations were largely ignored until 1946, when the United States established an Indian Specific Claims Commission, intensifying calls for a similar body in Canada. Over the next 15 years, parliamentary commissions examined First Nations grievances against Canada, and recommended the creation of an independent administrative tribunal to adjudicate First Nation claims, but successive government bills seeking to establish such a body were unsuccessful. In 1973, the Supreme Court of Canada issued its decision in Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney General) recognizing Aboriginal title to land as a legal right in Canada, putting pressure on the federal government to establish a process for resolving First Nation grievance related to the fulfillment of historic treaties and Canada’s management of First Nation lands, monies and other assets. Since 1973, the Specific Claims Policy has provided a voluntary alternative dispute resolution process allowing Canada to discharge its outstanding legal obligations through negotiated settlements rather than through the courts.

The Specific Claims Policy underwent its last major reform in 2007 (Justice at Last), with the addition of the Specific Claims Tribunal and legislative framework adding discipline and binding judicial decisions to the process, and remains the current model in place today. The Justice at Last: Specific Claims Action Plan, introduced in 2007, was intended by Canada to improve the existing specific claims process and to address the backlog of claims in the system. Justice at Last proposed reforms to the specific claims process that would follow four pillars of implementation: "ensure impartiality and fairness, greater transparency, faster processing and better access to mediation"Footnote 6.

Released in November 2016, the OAG report 6—First Nations Specific Claims—Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, concluded that the Department did not adequately manage the resolution of First Nations specific claims and that funding cuts and lack of information sharing between the Department and First Nations posed barriers to First Nations’ access to the process for resolving specific claims. The OAG made ten recommendations for improving fairness and transparency and the Department agreed with all of them. In 2016, the legislated five-year review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, Re-Engaging: Five-Year Review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, also made a number of recommendations, including a renewed and more positive process involving conciliation and engagement between the Government of Canada and First Nation.

Sparked by the legislated five-year review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act and the 2016 report of the OAG, Canada committed to work jointly with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and First Nations to substantively reform the SCP and policy. In 2017, in response to recommendations made by the OAG’s 2016 report, Canada and the AFN launched the Joint Technical Working Group (JTWG), "with a mandate to review the specific claims policy and process and to make recommendations for change"Footnote 7.

Following the AFN’s adoption of Resolution 67-2017, "Rejection of the Recognition and Implementation of Indigenous Rights Framework and Associated Processes", the AFN convened the "Four Policies and Nation Building Policy Forum" to facilitate discussion and establish First Nations principles to form the basis of any approach with the federal government. Specific Claims was one of the four policies chosen for focus and reform.

In 2017, following two national discussions with First Nations, Chiefs-in-Assembly passed AFN Resolution 91-2017, "Support for a Fully Independent Specific Claims Process", calling on Canada to work in equal partnership with the AFN and First Nations to develop a 'fully’ independent process with "the goal of achieving the just resolution of Canada’s outstanding lawful obligations through good faith negotiations"Footnote 8. Most recently, AFN Resolution 07-2020 "Jointly develop a fully independent specific claims process" demonstrates the continued First Nations’ support for a fully independent specific claims process. Additionally, this resolution lists the principles identified by First Nations during the 2019 AFN dialogue process that, according to the AFN, must underpin a new, fully independent process, which include: the honor of the Crown; independence of all aspects of claims resolution; recognition of Indigenous laws; and no arbitrary limits on financial compensation.

In Budget 2019, the Government of Canada re-emphasized its commitment and cited the settling of specific claims as a key step in the advancement of reconciliation and redressing past wrongsFootnote 9. Moreover, CIRNAC’s 2019-2020 Departmental Plan emphasized that the government would "continue to work with First Nations, in collaboration with the JTWG, on process, policy and legislative reforms to the specific claims process. This work will include exploring options on enhancing the independence of the processFootnote 10."

Canada’s Bill C-15Footnote 11 affirms the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides a framework to advance the Government of Canada’s implementation of the Declaration. In a January 2020 paper, the Union of British Columbian Indian Chiefs called for an independent specific claims process that includes the recognition and integration of Indigenous laws, in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)Footnote 12.

Canada is working with the Assembly of First Nations, other First Nation organizations and First Nations in a spirit of co-operation and renewal to find fair and practical ways to improve the specific claims process. These discussions began in June 2016. This ongoing work is looking at recent court and tribunal decisions and previous reviews of the process.

The Assembly of First Nations led a policy reform engagement exercise with First Nations in Fall 2019, and shared the report of policy reform options with CIRNAC in fall 2020.

Reform measures are expected concerning the existing Specific Claims Policy, process and the Specific Claims Tribunal Act.

1.3 Program Profile

Canada is responsible for the administration and operation of the specific claims policies and process. CIRNAC supports the Government of Canada’s accountability for legally-binding treaties and agreements made with First Nations, and the government’s duty to honour these past commitments, through policy, processes, and guidelines for assessing and settling specific claims through negotiationFootnote 13.

Key activities of the SCB, with support from the Department of Justice (DOJ), include the assessment of the historical and legal facts of a claim, the negotiation of settlement agreements, supporting the presentation of Canada’s interests before the Specific Claims Tribunal (also referred to as the "Tribunal"), and payment of monetary compensation to First Nations pursuant to the terms of a settlement agreement or an award from the Tribunal.

Before a claim is filed, historical claims research is done by individual First Nations, some tribal councils or by Claims Research Units (CRUs). The first step in filing a claim is generally when a First Nation applies for fundingFootnote 14 to do preliminary research, which is then followed by the claim development by the FNs legal counsel, and historical researcher. The historical research could be executed by a Claims Research Unit (UBCIC, for example), or by an independent contractor. First Nations undertake claims research and development independentlyFootnote 15.

Consistent with the Specific Claims Tribunal Act (SCTA), which defines "specific claims", describes the mandate of the Specific Claims Tribunal, establishes timelines within which certain phases of the process need to be completed, and defines certain elements of the policy and process, the program relies on the following process for resolving specific claims (see Appendix B for a pictorial description of the process as described in the OAG report, 2016)Footnote 16:

- Submission - The First Nation submits the claim to the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations.

- Initial review of claim - The government reviews the claim and after a period of up to six monthsFootnote 17 determines if the claim meets the minimum standard for claim submissions. If the claim meets the minimum standard, it is filed with the Minister and moves to the assessment phase. If the claim does not meet the minimum standard, the claim is returned to the First Nation who has the option to resubmit the claim with revisions, and restart the process.

- Assessment phase - SCB and DOJ assess the claim submission, within three years, to confirm the validity of the research and if the claim discloses a lawful obligation to the federal government, culminating in a decision whether to enter into negotiations. The First Nation is informed of the basis for the negotiation and is asked to indicate whether it is willing to engage in negotiations. Various steps occur within the 3 years: (1) Claims Research - The Research and Assessment Directorate performs additional research as needed to supplement evidence submitted by the First Nation; (2) DOJ Review and Assessment of Claim - DOJ Reviews and Assess Claim: DOJ assesses whether the claim discloses outstanding lawful obligation on the part of Canada based on a review of the First Nation submission and SCB documents; and (3) the Claims Advisory Committee stage: Research and Assessment Directorate reviews the legal opinion and prepares the Claims Advisory Committee recommendation document (which is a summary of the legal opinion) and letter to First Nations stating Canada’s position on the claim. The Claims Advisory Committee reviews the documents, a Claims Advisory Committee meeting is set up, the claim moves up for approval, and Canada’s position letter is sent to the First Nation. If the claim is not accepted for negotiation, the First Nation may choose to resubmit the claim with new evidence or to file the claim with the Specific Claims Tribunal. If the First Nation chooses to resubmit the claim with new evidence, the assessment of the claim resumes and further decisions are taken as to whether the claim can be negotiated

- If the assessment of a claim is not completed within the legislated three-year timeframe, or if it is not accepted for negotiation by the Minister, the First Nation can file the claim with the Specific Claims Tribunal; for adjudication. The Tribunal, made up of judges, can make binding decisions on validity and compensation. Under the SCTA, specific claims are not subject to limitations periods that could otherwise be used to defend against them given they often arose more than a century ago.

- Negotiation and Settlement - Successful negotiation of a claim results in an agreement between the First Nation and the federal government. The final agreement is ratified and signed, final releases and compensation are provided, and the claim is settled. If after three years, a negotiated settlement has not been reached or if the First Nation is not satisfied with the progress of negotiations, they have the right, under the SCTA, to refer the claim to the Specific Claims Tribunal. However, negotiations may continue beyond three years if the First Nation chooses. If a settlement is reached, it moves forward to implementationFootnote 18.

The cohort methodology used in this evaluation for analytical purposes in order to demonstrate how claims have moved through their life cycle stages does not give a full picture of the SCP’s output. To give the reader a better sense of volume, the following table includes what the program considers to be key outputs for the evaluation period.

| Fiscal Year | Claims Received | Claims Filed | Accepted for Negotiations | Not Accepted for Negotiations | File Closed | Settled Through Negotiations | SCT Awards Implemented | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | $ Value | # | $ Value | ||||||

| 2013-14 | 44 | 34 | 23 | 23 | 17 | 15 | $369,287,076.60 | $0.00 | |

| 2014-15 | 94 | 41 | 15 | 21 | 18 | 15 | $35,972,152.64 | $0.00 | |

| 2015-16 | 34 | 66 | 13 | 11 | 22 | 11 | $27,431,213.46 | $0.00 | |

| 2016-17 | 60 | 40 | 22 | 16 | 5 | 17 | $252,580,124.00 | 1 | $6,900,187.35 |

| 2017-18 | 39 | 47 | 41 | 3 | 9 | 31 | $1,279,145,551.00 | 1 | $16,263,719.76 |

| 2018-19 | 54 | 55 | 57 | 4 | 4 | 48 | $627,047,325.73 | 0 | $0.00 |

| 2019-20 | 50 | 49 | 70 | 8 | 2 | 33 | $798,773,022.73 | 0 | $0.00 |

| TOTAL | 375 | 332 | 241 | 86 | 77 | 170 | $3,390,236,466.16 | 2 | $23,163,907.11 |

| Source: Program time series statistics, Excel spreadsheet (CIRNAC, 2022). | |||||||||

Specific claims may be filed with the Specific Claims Tribunal if they have been previously filed with the Minister and any of the following four conditions have been met: (1) the Minister has not accepted the claim for negotiation (in whole or in part); (2) three years have elapsed since the claim was filed and the First Nation has not been notified of Canada’s position on the claim; (3) during the first three years of negotiations, if the Minister gives written consent to the filing of the claim with the Tribunal; and (4) three years have elapsed since the claim was accepted by Canada for negotiation (in whole or in part) and Canada and the First Nation have not reached a negotiated settlement agreement. The criteria for filing a claim with the Tribunal are set out in the Specific Claims Tribunal Act.

The federal government’s approval process for financial mandates varies depending on the size of the mandate and whether it relates to land. For example, the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs can approve financial mandates and finalize settlement agreements valued at up to $50 million; and Negotiated specific claim settlements valued at between $50 million and $150 million must be approved by the Treasury Board of Canada before they can be signed by the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs. Specific claim financial mandates of more than $150 million must go through the Cabinet approval process. Once a settlement is reached based on such a mandate, Treasury Board approval is required as part of the federal government process to ratify the settlement and obtain authority to issue settlement funds to the First Nation.

All specific claim settlements involving the regularization of interests in land, regardless of size, (usually this arises in claims where a historic surrender needs to be reconfirmed under the Indian Act in order to resolve the claim with certainty for third parties) must be approved by the Governor-in-Council before they can be finalized. This includes seeking an Order-in-Council. After all the approvals have been obtained, the minister signs the settlement on behalf of the Government of Canada. Following this, there is a 45 day requirement for Canada to pay the compensation monies to the First Nation.

Program delivery and governance of the SCP is the primary responsibility of the Specific Claims Branch, through the Negotiations and Operations Directorate, the Research and Assessment Directorate and the Policy and Litigation Management Directorate. There is also a BC Specific Claims Resolution Directorate.

The Negotiations Support Directorate, outside of the SCB and situated in the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector is responsible for the administration of contribution and loan funding requests to support First Nations’ participation in the specific claims process (research and development of claims, Tribunal litigation and negotiations).

The Claims Advisory Committee (with CIRNAC, ISC and DOJ membership and other departments participation as required) reviews recommendation packages prepared by SCB (with DOJ support), and makes a recommendation to the Minister of CIRNAC on whether to negotiate a claim or not. This depends on whether the SCB and DOJ assessment results in a view that there is a breach of a lawful obligation. The Claims Advisory Committee also makes recommendations to the Minister on proposed financial mandates to seek to settle a claim.

ISC regions are responsible for implementation of settlement provisions if there is a land component (i.e., additions to reserves).

The Joint Technical Working Group (JTWG), which plays an advisory role only, rather than having any governance or decision-making role, was established to examine the specific claims process and to develop recommendations for improvements.

Key beneficiariesFootnote 19 from the resolution of specific claims include:

- First Nations – greater certainty over lands; cash/land settlement that can support community development; resolution of historical grievances; and, contributions to reconciliation;

- The Government of Canada – resolution of outstanding lawful obligations and historical grievances of First Nations, certainty over lands, settlements to First Nations to support community development, contributions to reconciliation;

- Provincial and territorial governments – greater certainty over lands; contributions to reconciliation;

- Local governments adjoining First Nation communities – improved relationships and enhanced ability to make plans respecting land management, natural resources and provisions of services; and

- Private Sector – improved confidence in their business and investment decisions respecting First Nation interests in lands and opportunities to partner with First Nations.

1.4 Program Narrative

The Specific Claims Branch, within Resolution and Partnerships Sector at CIRNAC, is responsible for the assessment and settlement of Specific Claims.

The Specific Claims Branch is organized in four Directorates:

- Research and Assessment Directorate;

- Negotiations and Operations Directorate;

- British Columbia Specific Claims Resolution Directorate; andFootnote 20

- Policy and Litigation Management Directorate.

The following activities are undertaken to support resolution of specific claimsFootnote 21 :

- an assessment of the historical and legal facts of the claim;

- the negotiation of a settlement agreement, if it has been determined that there is an outstanding lawful obligation;

- management of litigation that relates to specific claims, which includes participating in proceedings before the Specific Claims Tribunal, as well as managing civil litigation files from across Canada;

- payment of monetary compensation to First Nations, pursuant to the terms of a settlement agreement or award of the Specific Claim Tribunal;

- consideration of trends and relevant legal and policy developments and their impacts on specific claims, and identification of opportunities for claims resolution through bundling of claims or mandates;

- administration of the database on specific claims; and

- engaging with First Nations to gather feedback on how to improve the specific claims policy and process;

- policy and process administration;

- policy application, development and reform.

As indicated by the 2018 Performance Information ProfileFootnote 22, the SCP logic model (Appendix A), as carried out by the Specific Claims Branch, identifies that the program’s activities and outputs are expected to contribute to three immediate outcomes:

- Claims that meet the minimum standard are filed with the Minister;

- Canada’s outstanding lawful obligations are identified; and

- Claims are resolved through negotiation or Tribunal decisions.

The immediate outcomes contribute to the attainment of the program’s long-term outcomes:

- Justice for Claimants: The timely processing of claims identifying Canada’s outstanding lawful obligation and resolution of claims through negotiation or a binding Tribunal decision all contribute toward justice for claimants, which is the key long-term outcome. Through these transparent mechanisms, First Nations have an opportunity to pursue their claims against Canada and obtain resolution.

- Certainty for Government, Industry and all Canadians: Timely processing of claims contributes to certainty by ensuring that First Nations have mechanisms through which to pursue their claims. Identification of Canada’s outstanding lawful obligation contributes to certainty by providing knowledge of these obligations. Finally, resolution of claims through negotiation or binding Tribunal decisions contributes to certainty by determining and respecting, with finality, the rights of First Nations.

Together, these two long-term outcomes are expected to contribute to the SCP’s ultimate outcome that "Canada fulfills its long-standing obligations to First Nations arising out of treaties, and the administration of lands, band funds and other assets".

This in turn contributes to the Departmental Result and Core Responsibility, "Rights and Self-Determination", in which "past injustices are recognized and resolved"Footnote 23.

1.5 Program Alignment and Resources

The program consists of two streams :

- Grants to First Nations to settle specific claims negotiated by Canada and/or awarded by the Specific Claims Tribunal, and

- Contributions for the negotiation and implementation of treaties, claims and self-government agreements or initiatives

Table 2 provides actual spending for fiscal years 2013–14 through 2019–20 for the Specific Claims Process.

| Vote | Expenditure Type | 2013–14 ($) | 2014–15 ($) | 2015–16 ($) | 2016–17 ($) | 2017–18 ($) | 2018–19 ($) | 2019–20 ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote 1 | Salaries | 7,434,364 | 6,804,507 | 6,601,391 | 7,224,225 | 8,539,116 | 8,451,267 | 6,149,834 |

| Operations and Maintenance | 821,745 | 734,422 | 1,045,247 | 1,766,993 | 1,802,755 | 4,550,717 | 15,116,768 | |

| Employee Benefit Plan | 1,197,603 | 1,044,063 | 1,003,896 | 1,047,391 | 1,132,098 | 1,288,709 | n/a | |

| Vote 1 Total | 9,453,712 | 8,582,992 | 8,650,534 | 10,038,609 | 11,473,969 | 14,290,693 | 21,266,602 | |

| Vote 10 | Grants | 369,287,077 | 35,972,153 | 28,996,054 | 383,092,933 | 1,297,169,216 | 630,282,403 | 799,569,194 |

| Contributions (Negotiations) | 1,300,000 | 8,801,778 | 8,891,551 | 10,739,618 | 11,149,684 | 10,519,290 | 13,160,091 | |

| Contributions (Policy) | 9,634,489 | |||||||

| Vote 10 Total | 380,221,566 | 44,773,931 | 37,887,605 | 393,832,551 | 1,308,318,900 | 640,801,773 | 812,729,285 | |

| Total | 389,675,278 | 53,356,923 | 46,538,139 | 403,871,160 | 1,319,792,869 | 655,092,386 | 833,995,887 | |

| Source: Program financial information (Transfer Payments for Specific Claims) | ||||||||

It should be noted that additional funding, is available to support First Nations in participating in the various stages of the broader specific claims resolution process. This funding is administered by the Negotiation Support Directorate in the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector, and consists of the following funding amounts and mechanisms:

- $12.1 million per year in contribution funding to support First Nations in developing their claims ($8 million of this amount was provided through Budget 2019 for a five-year period ending in 2023-24);

- $2 million per year in contribution funding to support First Nations in litigating their claims before the Specific Claims Tribunal; and

- Loan funding to support First Nations in negotiating the resolution of their claims. Up to $25.9 million in loan authority is available for these loans each year. (Note: Settlements managed by SCB include an additional amount to cover the cost of such loans taken out by First Nations during the course of negotiations (i.e., loans are not a deduction from settlements; rather they are paid from an addition to settlements)).

These grants and contributions funding programs are governed by Treasury Board terms and conditions and loan funding by Order in Council, as well as the Financial Administration Act. The Negotiation Support Directorate administers the Negotiation loans in accordance with published Negotiation Loan Funding Guidelines as well as the Research funding which is administered through a call for proposals process. Tribunal support funding is administered through an application process also managed by Negotiation Support Directorate.

SCB administers the program through "Grants to settle specific claims", which is the authority for the payment of specific claims settlements up to $150 million in value and for compensation awards by the Specific Claims Tribunal. The payment of specific claims settlements above $150 million requires Cabinet approval and a separate source of funds from the fiscal framework.

2. Evaluation Scope, Approach and Design

An Evaluation Working Group was convened to guide the evaluation process and to ensure diverse perspectives were reflected in the evaluation, with members from the evaluation team, SCB program representatives, including regional representatives, the AFN (and additional members suggested by the AFN, including the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs). The Evaluation Working Group provided feedback on the evaluation issues and methods and were included at key stages in the evaluation.

The evaluation focused on the implementation of the Specific Claims Assessment and Settlement process (also referred to herein as "the program" or the "SCP") from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2020. In scoping the evaluation it became clear that the overall Specific Claims Process (SCP) involves two important interfacing departmental activities/program areas that, while outside the "mainstream" specific claims assessment and settlement process which is the subject of the evaluation, they contribute nonetheless to the overall Specific Claims Process picture. These include the upstream (pre-) activities related to the funding for First Nations to undertake independent research to develop their claim in the first place and the downstream post-program activities (implementation). While the funding was specifically not examined and thus not part of the scope of the evaluation per se, because these activities interface with the SCP, decision was taken, on the guidance of the Evaluation Working Group, to ensure that information and views about these important aspects (funding to research claims) and implementation was collected by key informant interviews and case studies to ensure that the evaluation portrayed a complete picture of the overall Specific Claims Process beyond the focus of the evaluation at the program level.

Finally, while the effectiveness and efficiency of the claims assessment and settlement process, impacts the rate at which First Nations file claims with the Tribunal, the Tribunal process is considered to be outside the scope of this evaluation.

The evaluation’s design and data collection methods were guided by Treasury Board’s Policy on Results (2016).

This evaluation focuses on relevance, design and delivery and effectiveness as they relate to the SCB’s implementation of the Specific Claims program and in the context of the overall SCP. With regards to issues of relevance, less emphasis was placed on the question of whether or not there is continued need for the program, as the Government of Canada is accountable for fulfilling statutory and fiduciary obligations to First Nations as well as upholding the honour of the CrownFootnote 24. In answering this question, the evaluation emphasized a greater focus on whether or not the program is relevant in its current form and analysed to what extent the program addresses the needs of First Nations communities. The evaluation questions and issues about design and delivery and the performance of the program were organized to correspond to the program’s existing logic model.

The evaluation methods included:

- Document review;

- Review of SCP performance and financial data (from the specific claims database);

- 51 key Informant interviews (with federal government representatives, Indigenous governments, Indigenous Representative Organizations and Claims Research Units, and other Indigenous representatives); and

- Eight case studies of specific claims in various stages of the process, including a review of core claim documents and 20 key informant interviewsFootnote 25. The case studies considered the experiences of First Nations involved at various key stages in the SCP, examined the role of the SCB and identified key challenges at various stages of the process.

The use of multiple lines of evidence and triangulation in analysis increased the reliability and validity of the evaluation findings and conclusions.

2.1 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Most evaluations face constraints that may affect the reliability of findings.

Table 3 outlines the limitations encountered during this evaluation as well as the mitigation strategies put in place to increase the reliability of the evaluation findings.

| Limitation | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| The evaluation scope focusses on the SCB claims assessment and settlement process. The effectiveness and efficiency of the claims assessment and settlement process is dependent on upstream research conducted by First Nations to prepare claims for submission, which is outside the scope of the program. | The research conducted by First Nations is one variable that contributes to volume of claims submitted, which in turn impacts the SCB’s part in claims assessment and settlement (e.g., meeting timelines, backlogs, resource adequacy). Excluding the preparatory work conducted by First Nations from the evaluation would not provide a complete picture of the SCP. | Key informant interviews were held with those knowledgeable about this early claims research and development, including department representatives, First Nations and Claims Research Units. Case studies examined this part of the SCP. The Evaluation Working Group includes members familiar with claims research and development. |

| The evaluation scope focusses on the SCB claims assessment and settlement process. The effectiveness and efficiency of the claims assessment and settlement process impacts the implementation of settlement provisions, particularly those with land components, involving ISC regional offices (i.e., Additions to Reserve). Settlement implementation is outside the scope of this evaluation | The efficiency and effectiveness of settlement implementation impacts ISC regional offices, and the relationship between Canada and First Nations. Excluding settlement implementation from the evaluation would not provide a complete picture of the SCP. | Key informant interviews were held with those knowledgeable about settlement implementation, including ISC regions and First Nations. Case studies examined this part of the specific claims process. The Evaluation Working Group includes members familiar with this part of the specific claims process. |

| The evaluation scope focusses on the SCB claims assessment and settlement process. The effectiveness and efficiency of the claims assessment and settlement process, impacts the rate at which First Nations file claims with the Tribunal. The Tribunal process is outside the scope of this evaluation. | The efficiency and effectiveness of the specific claims process is one variable that contributes to the volume of claims filed with the Tribunal, and which in turn impacts the SCB (e.g., required to be involved in Tribunal process, claims returned to the mainstream specific claims process). Excluding the Tribunal process from the evaluation would not provide a complete picture of the SCP. | Key informant interviews were held with those knowledgeable about the Tribunal process, including First Nations and the SCB. Case studies examined the Tribunal process. |

| The evaluation could not comprehensively assess performance against expectations for five of the nine indicators because program performance targets were not set (for four indicators), or the method to calculate performance was unclear (for one indicator). There was also apparent misalignment between indicators and outcomes for two outcomes. | The evaluation does not provide an exhaustive assessment of performance against five of the six SCP outcomes. | Key informant interviews were used to supplement performance data. |

| Detailed data about human resources (e.g., number of Full Time Equivalent (FTE)’s, average number of files per FTE, rates of attrition) was not available for the evaluation. | The evaluation was not able to provide more insight into some of the human resource issues raised by respondents internal to the SCB. | Findings related to human resource issues were made only when a high proportion of respondents held similar views. |

3. Relevance: Continued Need

Resolution of specific claims remains a clear priority for First Nations and Canada has a continued obligation to right past wrongs.

The Specific Claims Policy recognizes that the Crown has sometimes failed to uphold its lawful obligations under historic treaties or has mismanaged First Nation lands, monies and other assets for which it is responsible under the Indian ActFootnote 26. This includes both historic and contemporary breaches. Specific claims are made by a First Nation against the federal government for its failure to discharge lawful obligations related to these past grievances.

Settlement funding can provide First Nations with a solid foundation to invest in their people and economies, support community development and self-sufficiency, and restore their capacity to participate in regional economiesFootnote 27. Claims and related litigation are among the federal government’s largest outstanding acknowledged contingent legal and financial liabilitiesFootnote 28. Canada has a legal obligation to resolve these claims, and the Specific Claims Policy provides a mechanism to do so through negotiation. This obligation did not change during the time period being evaluated, and remains pertinent today. Addressing these past wrongs is a cornerstone of the Government of Canada’s reconciliation agenda (for more information, see Section 3.2 Alignment with Federal Priorities).

First Nations bear a substantial cost to research and negotiate claims to enable them to prepare their claim prior to participating in the SCP. Respondents reported that scarce resources are often diverted from other important priorities (see Section 3.10: Capacity and Resources). First Nations assess the receiving environment (i.e., within CIRNAC and in many cases a provincial or territorial government) for a claim before its development and submission, and as reported in the case studies (e.g., Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation Treaty 22 and Treaty 23, and Smith’s Landing First Nation Annuity Claim), how the claim fits into their strategic plans and priorities (e.g., towards self-government) to ensure the highest return for their investment of scarce resources.

Changing jurisprudence has resulted in more favourable conditions for First Nations to research, develop and submit claims.

Changes to case law during the time period being evaluated have resulted in more favourable conditions for First Nations to research, develop, and submit claims. Tribunal or court decisions over the years have set precedents that impacted the way that Canada assesses claims, which in turn have been more favourable to some First Nations. Williams Lake is an example of a major one (additional examples are included in the report).

The impact of changing jurisprudence is illustrated by the Tribunal’s 2014 Driftpile First Nation Claim with respect to determining the strength of evidence and the 2016 Huu-ay-aht First Nation Claim decisions with respect to determining present-value, gleaned as part of case studies:

- In its examination of the evidence brought forward by Canada and the Driftpile First Nation, the Tribunal concluded that since neither party could prove their perspective, the fiduciary onus was to be borne by Canada. In light of the Tribunal’s decision, the SCB and DOJ reconsidered the strength of Canada’s defence in the Beecher Bay First Nation Rocky Point Village Site Claim, and concluded it was weak.

- Until the December 2016 Huu-ay-aht and Beardy’s Tribunal decisions there was limited judicial guidance on how the legal principle of equitable compensation should be applied to update historic values in Indigenous claims and the parties typically settled on the basis of 80% CPI and 20% compounded Band Trust Fund rates, which reflects savings rates in Canada over the last 100 years. These judicial decisions provided guidance indicating that the application of 100% band trust fund rates is appropriate for updating known values. Subsequent judicial decisions at the Tribunal and Supreme Court of Canada indicated that for more speculative historic values a more nuanced approach is needed, which takes into account whether the nominal values being updated are realistic. SCB has developed guidance regarding the implementation of these concepts in a negotiation environment. This decision was a turning point for many First Nations contemplating, developing or in active negotiation of claims. At the time of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation decision, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation was actively negotiating its Global Settlement Project, and had received a compensation offer from Canada in 2014. Given the Tribunal’s decision, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg proposed reviewing the offer, and following a joint study of the spending and saving habits of Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, agreement was reached on an alternative to the 80/20 approach to update historical loss. This led to a 50% increase in Canada’s settlement offer.

First Nations feel more willing to engage in the claims resolution process.

Despite longstanding and widespread criticisms of the Specific Claims Process, including in the 2016 OAG report where it was concluded that Canada was failing in its duty to manage specific claims resolution, and some serious constraints to participation (including capacity to undertake the initial research required), First Nation respondents reported an increased willingness to engage in the claims resolution process with Canada, particularly since 2015. The main reasons given were Canada’s adoption of a more collaborative, flexible and creative approach to claims processing, many First Nations preference for negotiation rather than litigation, and a more trusting and constructive working relationship.

Federal officials cited the government’s 2015 commitments to achieve reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and to implement the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC)Footnote 29.

The Principles Respecting the Government of Canada's Relationship with Indigenous Peoples, released in 2017, were specifically mentioned by First Nations and federal respondents in considering the evaluation issue of relevanceFootnote 30. Federal respondents agreed that they served as a backdrop, enabling negotiation teams to think differently, and be more innovative and flexible, as gleaned by case studies:

- The Principles were raised by the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg negotiation team as the catalyst to review Canada’s 2014 compensation offer in light of the Tribunal’s decision on the Huu-ay-aht First Nation claim regarding Canada’s 80/20 method, to reconcile Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg’s language preferences and protect third party interests within the limits of the Specific Claims Policy to resolve negotiation impasse over the "absolute surrender" language typically required in a settlement agreement, and to adjust the threshold for ratification from a majority of electors to a "double majority" of electors.

- The Principles also served to encourage federal officials to reconsider the strength of Canada’s defence in the Beecher Bay First Nation Rocky Point Village Site Claim in light of the 2014 Tribunal decision on the Driftpile First Nation Claim, and research evidence that led the Claim Advisory Committee to recommend the claim for negotiation.

The volume of claims submitted by First Nations is not expected to diminish in the foreseeable future.

During the evaluation period, and based on the data from the Specific Claims Database that was made available for the evaluation, there were 375 claim submissions received by CIRNAC. The number of claims submitted has fluctuated year-to-year, without any evident annual pattern, the lowest being 39 in 2017–18 and the highest 94 in 2014–15. In 2018–19 and 2019–20 there were 54 and 50 claims submitted respectively. Of the 375 submissions over the evaluation period, 93% (n=350) met the minimum standard and were filed with the Minister. Table 4 in the report provides an illustration.

According to recent data from the program, as of March 31, 2020, there were 1916 claims in the Specific Claims Inventory: 150 in assessment, 332 in negotiations and 62 under the purview of the Specific Claims Tribunal (Table 10)Footnote 31 .

In terms of settlements, Budget 2019 noted that as of March 2019, the federal government had settled 68 specific claims since November 2015, which was a 40% increase over the number of specific claims settled from 2012 to 2015.

Given the more favourable conditions for First Nations to submit claims, and a greater willingness on their part to participate in the process, the volume of claims is not expected to diminish in the long-term, particularly as First Nations and their legal counsel reported inventories of claims not submitted, and new research is revealing additional historic and contemporary breaches.

3.1 Relevance: Alignment with Federal Priorities

The intent of the SCP strongly aligns with the federal priorities to achieve reconciliation with Indigenous peoples through a renewed, nation-to-nation, government-to-government relationship based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership. However, opinions varied in regards to the extent of alignment possible for the current SCP.

The SCP aligns strongly with federal priorities, particularly reconciliation and supporting nation-to-nation relationships. Settling claims improves the lives of First Nations and contributes to the advancement of reconciliation. Often, where specific claims have been settled, it has resulted in an improvement in the lives of First Nations people, and has also strengthened relations between Canada and First Nations, and between First Nations and the communities that surround them.

The government is committed to renewing its relationship with Indigenous peoples based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnershipFootnote 32. Treaties between First Nations and the Crown are of the utmost value in ensuring a strong and collaborative relationship between the federal government and First NationsFootnote 33. Budget 2019 drew a connection that settling specific claims is one means to advance reconciliationFootnote 34. The SCP is viewed as a mechanism to help right past wrongs and address longstanding grievances of First Nations through a voluntary process to seek resolution of claims through negotiations, rather than through the court system. This is intended to renew relationships and advance reconciliation in a way that respects the rights of First Nations and all CanadiansFootnote 35. Most First Nations agree with this perspectiveFootnote 36.

Many of those interviewed from different interview categories, were of the view, that in the negotiation process, there are attempts made by Canada to minimize liability and mitigate risk and that this is inconsistent with the pursuit of reconciliationFootnote 37. As noted above, to improve specific claims, and so advance reconciliation, the federal government is working with the AFN (supporting a nation-to-nation relationship) and other parties in a spirit of co-operation and renewal to find fair and practical ways to improve the specific claims policy and process through the AFN-led engagement sessions and the JTWG on Specific ClaimsFootnote 38.

3.2 Relevance: Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

While the objectives of the SCP align with federal roles and responsibilities, the manner in which the SCP has been implemented is regarded as lacking transparency, fairness and independence.

Specific claims arise from Canada’s failure to discharge lawful obligations with respect to pre-1975 treaties and the management of First Nation lands, monies and other assets. The federal government has legal obligations to First Nations in accordance with the Royal Proclamation and the Indian Act and other legal instrumentsFootnote 39, is accountable for legally-binding treaties and agreements made with First Nations, has a duty to honour these past commitments and has a treaty obligation to resolve and settle these claims in a timely mannerFootnote 40.

The honour of the Crown requires the Crown and its departments, agencies and officials to act with honour, integrity and fairness in all its dealing with Indigenous peoples. While the objectives of the SCP strongly align with federal roles and responsibilities, the manner in which the program has been implemented, including its very design, is widely regarded as lacking transparency, fairness and independence, as reported by interviewees and documents reviewed. Additionally, respondents reported that the existing SCP is slow, inflexible, and burdened by authority limits on financial mandates. However, First Nation respondents reported an increased willingness to engage in the claims resolution process with Canada, particularly since 2015. The main reasons given were Canada’s adoption of a more collaborative, flexible and creative approach.

3.3 Relevance: Alignment with CIRNAC Mandate and Priorities

The intent of the SCP aligns with CIRNAC'S mandate to renew nation-to-nation and government-to-government relationships between Canada and First Nations, to build capacity and support First Nations vision of self-determination. In practice, opinions varied on the extent of alignment possible for the current SCP.

Consistent with its overall mandateFootnote 41, CIRNAC has taken a more interest-based, collaborative and participatory approach to SCP, by working with First Nations to promote shared interests. According to interviews with the program, this includes providing forums for the parties to amicably, constructively and creatively work together to resolve old disputes and find common interests moving forward and where parties cannot agree, having impartial, credible and efficient forums for dispute resolution.

For example, CIRNAC has prioritized modernizing institutional structures and governance to support the SCPFootnote 42. As a member of the JTWG on Specific Claims, CIRNAC has been exploring innovative methods and negotiation processes to settle land claims, specifically to address priorities of funding to support the research and development of claims, an improved process to resolve claims with a value greater than $150 million, the use of mediation in negotiation processes, improving the clarity of public reporting, and enhancing the independence of the processFootnote 43.

While respondents agreed that the SCP supports First Nations to "build capacity and support their vision of self-determination" through claim settlements of financial compensation and/or land, the transactional, lengthy and litigious nature of the specific claims process was widely regarded as not advancing "a nation-to-nation and government-to-government relationship between Canada and First Nations". Even in those cases where the Principles Respecting the Government of Canada's Relationship with Indigenous Peoples were employed, such as in the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Global Settlement Project and Beecher Bay First Nation Rocky Point Village Site Claim, opinions about the impact on the relationship between Canada and First Nations differed sharply, with federal officials viewing the relationship to be more positive than First Nation respondents.

The intent of the SCP aligns with CIRNAC's strategic outcome to support good governance, rights and interests of First Nations. In practice, opinions varied on the extent of alignment.

Settling claims acknowledges historical wrongs, such as a failure to acknowledge treaty rights and promised lands and the process of settling claims intends to improve the lives of First Nations. The resolution of these longstanding injustices can restore some of the economic and social strength of communities and promote their self-sufficiency. This includes improving the quality of life for members of First Nation communities, promoting their economic prosperity and those of neighbouring communities, and enhancing the ability of the next generation of First Nations citizens to contribute to both their own communities and to Canada as a whole. The intent of the SCP aligns well to CIRNAC’s strategic outcome to support good governance, rights and interests of First Nations. However, in practice, opinions vary about the extent of the alignment due to factors in the process for bringing claims forward and the time periods to settle claims (to be discussed in later sections).

The SCP aligns with the Minister's 2019 mandate letter requiring ongoing work with First Nations to redesign federal policies on Additions to Reserve and on the SCP.

The mandate letters of the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) (2015)Footnote 44 and Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations (2017)Footnote 45 do not directly refer to the SCP, although there is reference to clarifying obligations and ensuring the implementation of pre-Confederation, historic, and modern treaties and agreements. The mandate letter of the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations (2019) states "Continue ongoing work with First Nations to redesign federal policies on additions to reserves, and on the Specific Claims processFootnote 46".

The SCP is consistent with the Minister’s mandate letters. For example, the AFN–Canada JTWG is a collaborative mechanism to improve the SCP. This is an example of current collaborative mechanisms that are in place, which respond to efforts being made to improve the program as per the Mandate letter and thus demonstrates alignment.

3.4 Relevance: Alignment with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Calls to Action

The Specific Claims Policy and process are aligned with the UNDRIP and the TRC but not fully in compliance with some Articles and Calls to Action. Of note, the team found no evidence that Indigenous customs, traditions, rules and legal systems have been systemically incorporated in the Specific Claims Policy and process.

As noted above, in 2015, the Government of Canada committed to achieve reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and to implement the Truth and Reconciliation of Canada Calls to Action. In 2016, the government endorsed the UNDRIP without qualification and committed to its full and effective implementationFootnote 47, and in December 2020, Bill C-15: The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, was introduced, described as a key step in renewing the government’s relationship with Indigenous peoplesFootnote 48.

Redress for past wrongs, such as dispossession of lands, territories and resources, is viewed as a fundamental human right by UNDRIP, and Call to Action 45 (iii) of the TRC, and in this, the overall objective of the SCP is aligned.

Interviewees were asked for their views on how well the assessment and settlement of Specific Claims complies with the UNDRIP and the TRC Calls to Action. While the Specific Claims process exists as a mechanism to address issues outside of the courts, and to do so in ways that are advantageous to First Nations parties, First Nations respondents were in broad agreement that the specific claims policy and process, did not fully adhere to, and meet the minimum standards (as prescribed by law), of the UNDRIP articles 8(2b), 27, 31 and 40Footnote 49, or the TRC Calls to Action 45(iii) and 45(iv)Footnote 50.

Specifically, these articles which related specifically to foundational issues around the transparency, fairness, independence, and integration of Indigenous laws and legal traditions in the Specific Claims Process have been raised repeatedly since concerted federal efforts to address specific claims began in 1974 with the establishment of the Office of Native Claims.

The government has made incremental efforts to address these through, for example, Outstanding Business: A Native Claims Policy (1982) and Justice at Last (2007), which established an independent Tribunal with the power to make binding decisions. For decades, First Nations have also been involved in policy reform.

Most recently, for example, the AFN–Canada JTWG was launched in 2017 to improve the specific claims policy and process.

3.5 Design and Delivery: Impartiality and Fairness

While the Tribunal has improved impartiality and fairness, First Nations perceive Canada to remain in an inherent conflict of interest by being both the object of the complaint and the one that has to resolve it - and have called for a fully independent SCP.

Justice at Last introduced an independent Tribunal to make binding decisions where claims are rejected for negotiation or when negotiations failFootnote 51. This was one of the main recommendations in the report of the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, and intended to address the widespread concern with "the apparent conflict of interest wherein the Government of Canada is both the causer and the 'resolver’" and "wherein a department that is the object of the complaint is also the one that has to resolve itFootnote 52."