Report of the Committee on the Science-Based Assessment of Offshore Oil and Gas Exploration and Development in the Eastern and Central Arctic

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Regulatory framework

- Climate change commitments

- Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait

- Hydrocarbon potential and basin prospectivity

- Proposal for scenarios for the Sverdrup and Saglek Basins

- Summary

- Conclusion

- References

- Annex 1: Additional details of the prohibition order

- Annex 2: Sovereignty and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

- Annex 3: Rights disposition in the Central and Eastern Arctic

- Annex 4: Call cycle for oil and gas rights

- Annex 5: Formation of oil and gas deposits

- Annex 6: Hydrocarbon potential

- Annex 7: Nunavut CO2 emission context

- Annex 8: Nunavut energy transition to greener energy

Disclaimer

This report is a summary of the work of the Committee and does not represent the individual views of the Committee representatives. For greater certainty, the content of this report is informational only and nothing in this report should be interpreted as advice or a recommendation that any entity pursue a particular course of action.

1. Introduction

On December 20, 2016, the Prime Minister announced that the Government of Canada would be designating "all Canadian waters as indefinitely off limits to future offshore Arctic oil and gas licensing, to be reviewed every 5 years through a climate and marine science-based life-cycle assessment."Footnote 1 The Government of Canada later committed to "freezing" the terms of the existing licences in the Arctic offshore, remitting the balance of any financial deposits related to licences to affected licence holders and prohibiting all offshore oil and gas activities for the remainder of the first 5-year period (later extended to Dec. 31, 2022).Footnote 2

In order to reflect regional diversity across the Canadian Arctic, 2 committees were established to oversee the assessment. The Western Arctic Committee, comprised of representatives from the Government of Yukon, the Government of the Northwest Territories, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, conducted a science-based assessment focused on the Beaufort Sea, including a study of potential greenhouse gas emissions and a survey of Arctic-capable well control and well containment technology and equipment.

The Eastern and Central Arctic CommitteeFootnote 3, with representatives from the Government of Nunavut, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, focused on matters pertaining to that part of the Nunavut offshore. These included the internal waters and territorial sea, for which oil and gas licensing is administered by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, as well as the adjacent continental shelf.Footnote 4

This report discusses the regulatory framework for oil and gas development, climate change commitments, and the Strategic Environmental Assessment for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. It also provides a detailed analysis of hydrocarbon potential and basin prospectivity in Nunavut, based on recent studies by the Geological Survey of Canada, and proposes development scenarios through which the feasibility of development, including potential impacts and benefits, can be examined in greater depth.

The committee was guided by the commitments made in the Nunavut Lands and Resources Devolution Agreement in Principle, signed August 15, 2019, to cooperate and coordinate with respect to oil and gas management, administration and development.

2. Regulatory framework

The regulatory environment for oil and gas operations in Nunavut is multifaceted, with requirements stemming from government acts and regulations, as well as the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. The scope of federal oversight ranges from the administration of rights to explore for and produce oil and gas to the regulation of operations to general laws related to environmental protection, climate change and the assessment of impacts. There are also territorial acts and regulations that apply to oil and gas activities, many of which are related to wildlife and the environment, and these will be expanded after the eventual devolution transfer.

2.1 The Nunavut Agreement and related federal acts

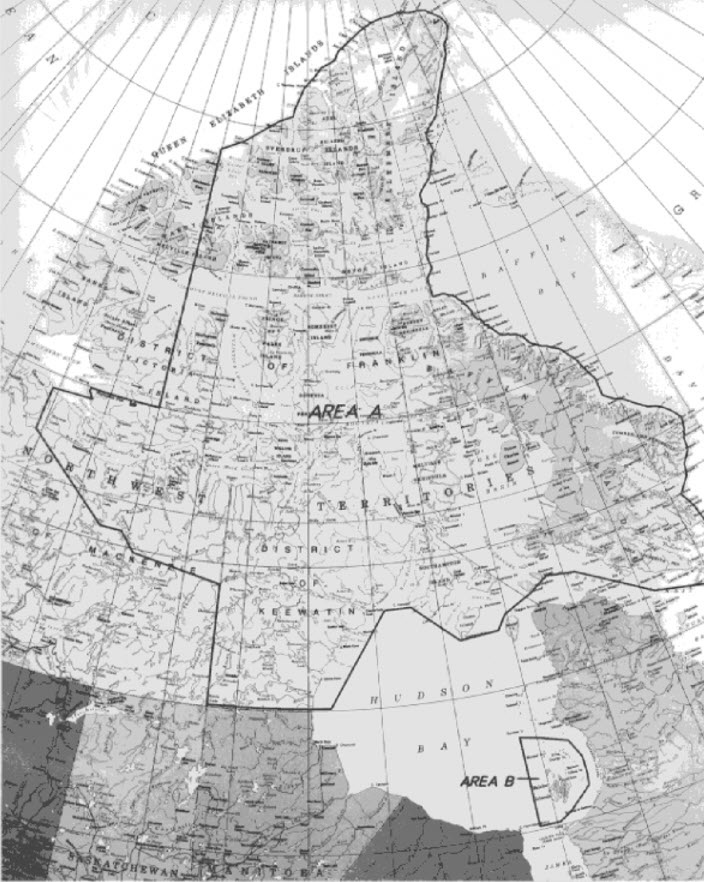

The creation of Nunavut on April 1, 1999 was an outcome of the largest Aboriginal land claims agreement in Canadian history, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, also known as the Nunavut Agreement, between the Government of Canada and the Inuit of the Nunavut Settlement Area (Figure 1).Footnote 5 The Nunavut Agreement was formally adopted on July 9, 1993.

The Nunavut Agreement sets the foundation for Inuit participation in "decision-making concerning the use, management and conservation of land, water and resources, including the offshore."Footnote 6 Provisions with respect to resource development, including the role of co-management boards, apply mostly to projects that take place, in whole or in part, within the Nunavut Settlement Area. However, some provisions also apply to projects within the Outer Land Fast Ice Zone, an area of Baffin Bay and Davis Strait adjacent to the Nunavut Settlement Area, or to 2 distinct zones beyond the Nunavut Settlement Area.Footnote 7

Many of the provisions related to the management of resource development in the Nunavut Settlement Area are enshrined in 2 federal acts: the Nunavut Planning and Project Assessment ActFootnote 8 and the Nunavut Waters and Nunavut Surface Rights Tribunal Act. These acts set out the powers, functions, objectives and duties of the Institutions of Public GovernmentFootnote 9. The Nunavut Planning and Project Assessment Act is particularly relevant to oil and gas development as it formally establishes the regulatory processes through which project proposals requiring authorizationFootnote 10 are reviewed in respect of land use conformity and environmental impact assessment.Footnote 11

Source: Map of the Nunavut Settlement Area, Schedule 3-1, Nunavut Land Claim Agreement.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Nunavut Settlement Area

Figure 1 is a map that depicts the boundaries of the Nunavut Settlement Area established in the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement. As shown on the map, the Nunavut Settlement Area is separated in 2 areas, Area A and Area B. Area A covers a portion of the Arctic Islands and mainland of the Eastern Arctic and adjacent marine areas. Area B covers the Belcher Islands, associated islands and adjacent marine areas in Southeastern Hudson Bay.

Another important feature of the Nunavut Agreement is the granting of title to Inuit of about 356,000 square kilometres of land. These Inuit Owned Lands include 150 parcels for which Inuit hold title to both the surface and subsurface ("Subsurface Inuit Owned Lands") and 944 parcels for which the Crown owns the minerals, oil, and gas ("Surface Inuit Owned Lands"). The only Inuit Owned Lands parcels in which there may be oil and gas potential are in the Norwegian Bay area (onshore) in the southeastern part of the Sverdrup Basin.

2.1.1 Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreements

Article 26 of the Nunavut Agreement states that before an operator can receive an operating permit for a major development project involving development or exploitation, but not exploration, of resources wholly or partly under Inuit Owned Lands it must first negotiateFootnote 12 an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement with the Regional Inuit Association. An Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement is a legally binding contract detailing the operator's commitments in areas such as employment, business opportunities, education and training.Footnote 13

If an Inuit Impact and Benefit Agreement is deemed appropriate, benefits may include (but are not limited to):

- Inuit preferential hiring

- scholarships

- Inuit training

- housing, accommodation, and recreation

- business opportunities (for example seed capital)

- language of workplace

- research and development

2.2 Federal acts and regulations

There are 2 general areas of federal responsibility for oil and gas, regulating operations and administering rights. These are covered, respectively, under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, which applies to all operations that take place in Nunavut, and the Canada Petroleum Resources Act, which applies only to frontier lands.Footnote 14 Several other acts and regulations are also applicable to oil and gas operations.

2.2.1 The Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act and the Canada Energy Regulator

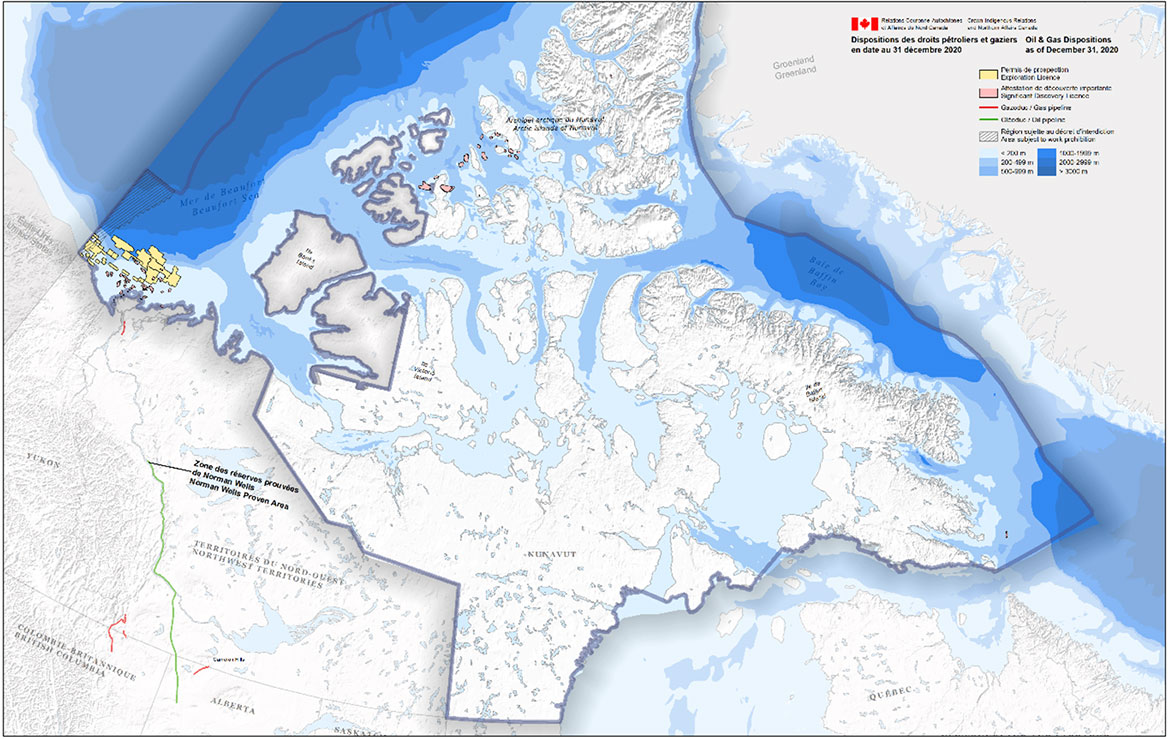

The Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act governs the exploration and drilling for and the production, conservation, processing and transportation of oil and gas in Nunavut, onshore and offshore, and the adjacent continental shelf (and the overlying water). It also applies to the waters adjacent to Yukon and the Northwest Territories as well as Pacific and Atlantic waters not under a federal-provincial joint-management arrangement (Figure 2). The act is intended "to promote safety, protection of the environment, the conservation of oil and gas resources, and joint production agreements."Footnote 15 Under the Frontier and Offshore Regulatory Renewal Initiative, the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act regulationsFootnote 16 pertaining to geophysical operations, exploration and development drilling, and the construction, certification and operation of production facilities are being modernized and will be amalgamated into Framework Regulations. The Canada Energy RegulatorFootnote 17 regulates all oil and gas activities in areas to which the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act applies. For the nearly 6 decades before the Canada Energy Regulator came into existence in August 2019 when the Canadian Energy Regulator Act became law, the National Energy Board oversaw energy companies and projects in Canada.

Notes: The Canada Energy Regulator regulates oil and gas activities in the Nunavut Area, Canada's waters in the Arctic, Pacific and Atlantic offshore areas not subject to a federal-provincial accord, and activities that transect provincial and territorial borders.

Text alternative for Figure 2: Canada Energy Regulator Areas of Jurisdiction

Figure 2 depicts the areas of jurisdiction of the Canada Energy Regulator over oil and gas work or activities. Hudson Bay, Nunavut and offshore areas in the Arctic, and the Pacific offshore are all regulated by the Canada Energy Regulator under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act. The Northwest Territories mainland is regulated by the government of the Northwest Territories' regulator. Onshore areas in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region are regulated by the Canada Energy Regulator under the Oil and Gas Operations Act. The Norman Wells Proven Area in the Northwest Territories is regulated by the Canada Energy Regulator under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act. The Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board regulates all offshore areas off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, The Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board regulates all offshore areas surrounding Nova Scotia. The Canadian Quebec Joint Accord Area, located in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, is under the jurisdiction of the Canada Energy Regulator. Pipelines regulated by the Canada Energy Regulator under the Canada Energy Regulator Act are also depicted on the map and are located in southern parts of Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Most of the Canada Energy Regulator regulated pipelines are located all over Alberta and extend to the Norman Wells Proven Area in the Northwest Territories. There are also Canada Energy Regulator regulated pipelines in British Columbia. The Canada Energy Regulator also regulates the pipeline for the Ikhil gas well under the Oil and Gas Operations Act. The pipeline is located in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, in the northwestern part of the Northwest Territories.

Environmental assessment

Any oil and gas project within the Nunavut Settlement Area that requires authorization under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act is subject to an environmental screening process carried out by the Nunavut Impact Review Board. An assessment under the Impact Assessment Act is required for an oil and gas activity that is authorized under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act and is a designated project outside the Nunavut Settlement Area. Environmental assessments for pipeline projects in the North and offshore crossing a territorial and provincial boundary fall under the Canadian Energy Regulator Act.

Review of offshore drilling

In December 2011, the National Energy BoardFootnote 18 released "The Past is Always Present – Review of Offshore Drilling in the Canadian Arctic – Preparing for the Future."Footnote 19 The National Energy Board consulted extensively with northern stakeholders and industry representatives during this review and examined the best available information on the hazards, risks and safety measures associated with offshore drilling in the Canadian Arctic. As an outcome of the review, the National Energy Board identified key filing requirements that companies applying to drill in Canada's Arctic waters would have to meet, providing greater regulatory clarity. The complete set of filing requirements is contained in the companion document to the review, "Filing Requirements for Offshore Drilling in the Canadian Arctic."Footnote 20 As part of the review, the National Energy Board also re-affirmed Canada's "Same Season Relief Well Policy", which requires that an applicant for an offshore drilling authorization "demonstrate, in its Contingency Plan, the capability to drill a relief well to kill an out-of-control well during the same drilling season."Footnote 21 Alternatively, an applicant could demonstrate that its proposed alternative method(s) to kill a blowout would meet or exceed the intended outcome of the Same Season Relief Well Policy (the Same Season Relief Well Equivalency determination.) The Canada Energy Regulator maintained these requirements.

2.2.2 The Canada Petroleum Resources Act and the administration of rights

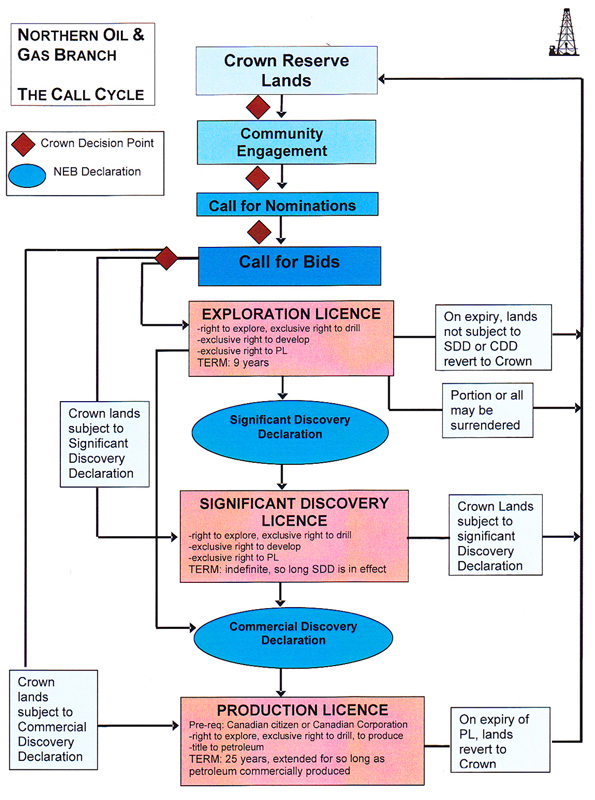

Issuance of licences

Under the Canada Petroleum Resources Act, licences are issued to allow for the exploration, development, and production of petroleum with respect to all frontier lands. The issuance of oil and gas licences under the Canada Petroleum Resources Act follows a transparent, competitive process.Footnote 22 The process for an exploration licence normally commences with a call for nominations by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada that allows the Department to gauge the level of commercial interest to explore on frontier lands. Next, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada may issue a call for bids, which is a formal invitation to companies to participate in an auction of the lands. During this stage, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada assesses the bids on a single bid criterion – the total amount a company commits to invest exploring the licence area. The Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada may issue an oil and gas licence to the company with the highest bid.

The administration of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act is divided between Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Natural Resources Canada. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada is responsible for the administration of the act north of its administrative boundary with Natural Resources Canada shown in Figure 3. The map also shows the existing significant discovery licences in Nunavut. More detailed maps are provided in Annex 3.

Text alternative for Figure 3: Canada Petroleum Resources Act: Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Canada Jurisdiction

Figure 3 is a map showing the position of exploration licences and significant discovery licences issued in the Arctic (Beaufort Sea, Arctic Islands and Eastern Arctic) within Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs' jurisdiction. Exploration licences are all located in the Beaufort Sea. Significant discovery licences are located in majority in the Beaufort Sea, in the same area as the exploration licences, and in the Arctic Islands. One significant discovery licence is located in Eastern Arctic, east of Baffin Island. The map also depicts the location of oil and gas pipelines in Northern British Columbia, Alberta, and in the Northwest Territories.

There are 3 types of oil and gas licence issued under the Canada Petroleum Resources Act:

Exploration licence

The exploration licence grants the exclusive right to the licence holder to explore for and to develop oil and gas resources in the licence area. The exploration licence has a fixed, 9-year term that may not be renewed. The holder of an exploration licence is required to submit a refundable work deposit, which may be forfeited if the licence holder does not meet its obligations to drill an exploration well within the term of the licence.

Significant discovery licence

When exploration results in a significant discovery, that is, if the licence holder drills an exploration well and proves that it has commercial potential, an application can be made for a Significant Discovery Declaration from the Canada Energy Regulator. Upon receiving a Significant Discovery Declaration, the holder of an exploration licence can apply to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada for a significant discovery licence for the area of the discovery. The significant discovery licence, like the exploration licence, grants the licence holder the exclusive right to explore for and develop oil and gas resources within the licence area. However, the term of the significant discovery licence is in perpetuity.

Production licence

The final type of licence is the production licence. A production licence grants an exclusive right to the licence holder to develop and produce oil and gas resources in the licence area. The term of a production licence is 25 years but may be extended as long as there is ongoing production. A full process map for rights issuance is provided in Annex 4.

Canada Petroleum Resources Act Review

On May 30, 2016, the Minister's Special Representative, Mr. Rowland Harrison, Q.C., finalized the Review of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act. The purpose of the Review was:

"to conduct a comprehensive review of the operations of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act, to engage with aboriginal groups, stakeholders and other interested parties as appropriate, and to provide recommendations as to whether potential amendments should be made to the Act as it applies to the Arctic offshore."

The Review concluded that while the scheme of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act is robust and should be maintained, the role of the act should be clarified. Harrison proposed 10 recommendations to the act to better reflect today's understanding of the technical and regulatory challenges in Canada's Arctic waters.

Benefits plans

A benefits plan is a statutory requirement under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act and the Canada Petroleum Resources Act. An operator engaged in the exploration and drilling for, and (or) the production and transportation of, oil and gas in Nunavut and the adjacent continental shelves is required to submit a benefits plan to the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada for approval.Footnote 23

Section 5.2(1) of the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act defines a benefits plan as a

"plan for the employment of Canadians and for providing Canadian manufacturers, consultants, contractors and service companies with a full and fair opportunity to participate on a competitive basis in the supply of goods and services used in any proposed work or activity referred to in the benefits plan."

While the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act does not provide any detail on what constitutes a benefits plan, guidelinesFootnote 24 prepared by the federal government specify that a benefits plan should include a project description as well as the operator's strategies for training and employment, procurement and contracting, and monitoring and reporting. The guidelines also outline the main principles, along with corresponding objectives, that an operator engaged in an oil and gas work or activity on frontier lands is expected to follow.

A benefits plan should ensure that Inuit and other Northern residents and businesses are provided an opportunity to participate in and benefit directly from oil and gas work or activities on Northern frontier lands. An operator is encouraged to develop and implement training and employment strategies as well as business and procurement processes that maximize Northern benefits.

Royalties

Federal frontier lands are subject to a generic royalty regime authorized under the Canada Petroleum Resources Act and prescribed through the Frontier Lands Petroleum Royalty Regulations.Footnote 25 While the federal government collects royalties, Inuit are entitledFootnote 26, under Article 25 of the Nunavut Agreement, to a percentage of revenue from all projects in which the resource is within the Nunavut Settlement Area or the Outer Land Fast Ice Zone. Inuit would be the sole beneficiary of resource revenue from production on Subsurface Inuit Owned Lands.Footnote 27

2.3 Devolution

Nunavut's regulatory environment will be further developed as the Government of Canada transfers responsibility for administration and control of public (Crown) land and resource management to the Government of Nunavut. This process, known as devolution, will allow Nunavummiut to make decisions on how public lands and resources are used and developed. On August 15, 2019, the parties signed an agreement-in-principle which will now serve as a guide for the negotiation of a final devolution agreement in Nunavut. These negotiations were still ongoing when this report was prepared.

The agreement-in-principle's chapter on administration of oil and gas resources sets out the framework for the transfer of responsibility for oil and gas management in the onshore, which will be detailed in the final Devolution Agreement. This will include a coordination and cooperation agreement between the Parties with respect to onshore and offshore oil and gas resources, particularly in areas where oil and gas resources straddle or potentially straddle the onshore and offshore. The signing of a Devolution Agreement will also allow, upon the written request of the Government of Nunavut, for the start of negotiations for an offshore agreement with respect to management, decision making, and resource revenue sharing.

3. Climate change commitments

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, to which about 197 countries are participants, is an international environmental treaty that came into force in 1994. It established as its ultimate objective "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system."Footnote 28 In December 2015 at a conference of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change held in Paris, 196 countries entered into the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty to strengthen the global response to climate change. It established a collective goal to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit that increase to below 1.5 degrees.

Since 2016, the Government of Canada has been working with provinces, territories, and Indigenous Peoples, to implement the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change.Footnote 29 This plan outlines over 50 concrete measures to reduce carbon pollution, help adapt and become more resilient to the impacts of a changing climate, spur clean technology solutions, and create good jobs that contribute to a stronger economy.

Building on the progress under the Pan-Canadian Framework, in December 2020, the Government of Canada announced A Healthy Environment and a Healthy EconomyFootnote 30, Canada's strengthened climate plan to accelerate the fight against climate change. Since the publication of the strengthened climate plan, the Government of Canada has announced significant new commitments and $17.6 billion in new, green recovery measures via Budget 2021.Footnote 31

The Prime Minister also announced, on April 22, 2021, that Canada's emissions reduction target under the Paris Agreement, known as its Nationally Determined Contribution, is 40 to 45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.Footnote 32 On June 30, 2021, the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act became law.Footnote 33 It formalizes Canada's target of net-zero emissions by the year 2050 and establishes a clear process to achieve this goal.

The Government of Canada has since made further announcements to its commitments in respect of climate change, including, among others:

- achieving a net zero electricity grid by 2035

- capping oil and gas sector emissions at current levels and reducing them at a pace and scale needed to achieve net-zero by 2050

- joining the Global Methane PledgeFootnote 34 on November 2, 2021 and committing to reducing total methane emissions by at least 30 percent below 2020 levels by 2030, including reducing oil and gas sector methane emissions by at least 75 percent below 2012 levels by 2030

4. Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait

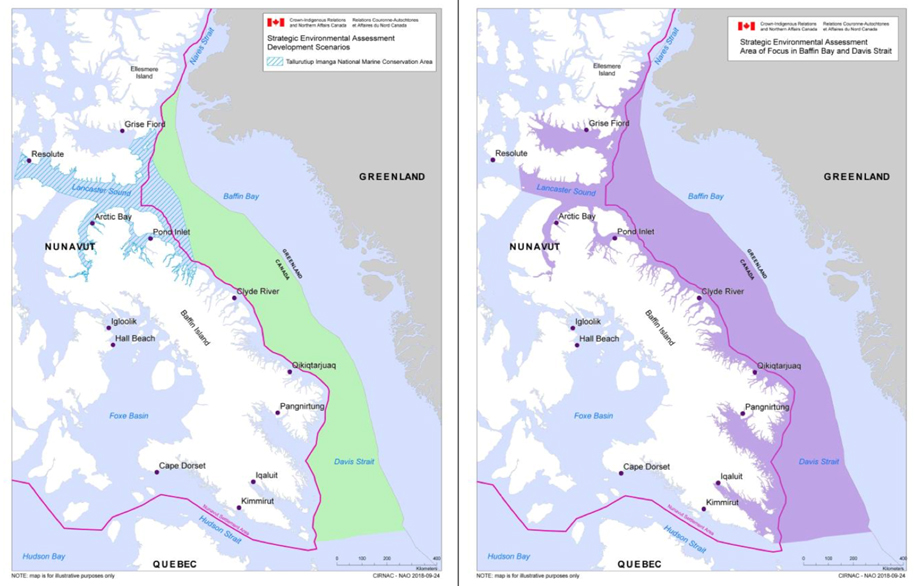

The Nunavut Impact Review Board coordinated the Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait, referred by the Minister of Northern Affairs in 2017. The Final Strategic Environmental Assessment Report was issued in July 2019.

The purpose of the Strategic Environmental Assessment was to better understand the possible types of oil and gas related activities that could be proposed in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait and the potential risks, benefits, and management strategies related to these activities. The Final Report described the hypothetical development scenarios that were examined to better understand what these activities could entail, identify gaps in available information, address questions and gauge public concern, and develop recommendations for further actions.Footnote 35 See Figure 4 for a map of the Strategic Environmental Assessment area.

The Final Report included 79 recommendations with respect to oil and gas development in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. It concluded that:

Given the importance of the marine environment to the well-being of Nunavummiut, significant gaps in knowledge of the environment necessary to support impact assessment, and an overall lack of regulatory, industry and infrastructure readiness in Nunavut, the 2016 moratorium on oil and gas development in the Canadian Arctic should remain in place for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait until such time as the key issues set out in this Report can be addressed. The Board expects that it will take at least a decade to complete the research, planning, and consultation identified as necessary prior to undertaking a reassessment by the Minister to determine if the moratorium should be lifted.

Text alternative for Figure 4: Area of the Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait

Figure 4 contains 2 maps. The map on the left depicts an area in Baffin Bay which is under the jurisdiction of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada where possible oil and gas development scenarios were considered. The area is outside the Nunavut Settlement Area and the Tallurutiup Imanga (Lancaster Sound) National Marine Conservation Area. In the map on the right, an area identified on the map, which is located in Baffin Bay, shows the greater area for which scientific information, Inuit Traditional Knowledge (Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit) and Inuit Traditional Knowledge as well as Inuit epistemology (Inuit Qaujimaningit) were gathered on the existing physical, biological, and human environments and the potential positive and negative impacts of the oil and gas development scenarios that were assessed. The line depicted on both figures illustrates the boundary of the Nunavut Settlement Area.

4.1 Addressing the Nunavut Impact Review Board's recommendations: Government of Nunavut Action Plan Discussion Paper

The Government of Nunavut has actively participated in the various stages of the Strategic Environmental Assessment and has substantial interest in respecting sustainable development in and around Nunavut, from environmental, socio-economic, cultural, and other vantage points. In the Government of Nunavut Action Plan Discussion Paper, an analysis of the Strategic Environmental Assessment and an Action Plan to address Nunavut Impact Review Board's recommendations are presented to set out priorities as guided by the results of the Strategic Environmental Assessment.

It is important to note that priorities could vary depending on several factors such as the priorities of partners, stakeholders and the communities. The Government of Nunavut is sharing the Action Plan for the purpose of discussions, hoping that some high priority action items could be delivered by the relevant partners and stakeholders. Initial comments are provided on the quality of the completed Strategic Environmental Assessment and the overall success in achieving its objectives. The Action Plan also sets out the priority of each of the recommendations, as well as the likely timeline and potential partners that would be involved. The actions are separated into the key topic areas below:

- spill prevention and response

- benefits regime and compensation

- scenario development

- sensitive areas, species at risk, and areas of importance for Inuit

- building a strong knowledge base

- regional planning, policy, and community engagement

- project mitigation, impact assessment, and monitoring

The implementation of this action plan is subject to the approval of the partners, engagement and consultation with the affected communities, availability of federal funding and collaboration between stakeholders.

5. Hydrocarbon potential and basin prospectivity

5.1 History of exploration and production

Hydrocarbon (oil and gas) exploration in the Eastern and Central Arctic began with seismic surveying in the early 1960sFootnote 36 and the drilling of the first well at Resolute Bay in 1963. Altogether, 150 exploration boreholes were drilled:

- 146 in the Arctic Islands

- 3 in Davis Strait

- 1 in Foxe BasinFootnote 37

One hundred and twenty-five of the holes in the Arctic Islands were in the Sverdrup BasinFootnote 38, resulting in 19 hydrocarbon discoveries:

- 9 of gas

- 7 of oil and gas

- 3 of oilFootnote 39

Two of the 3 holes drilled in Davis Strait in 1980 were in the Saglek BasinFootnote 40, Hekja O–71 and the nearby Ralegh N–18. The Hekja O–71 well, 80 kilometres east of Loks Land, an island at the mouth of Frobisher Bay, discovered the Hekja field, with 2.3 TcfFootnote 41 of gas. The Ralegh N–18 well, drilled to the north of Hekja, and Gjoa G–37, drilled just outside the Saglek Basin, were unsuccessful. All of the discoveries are subject to significant discovery licences.Footnote 42

The only production to date has been from the Bent Horn oil field on Cameron Island. Between 1985 and 1996, 1 to 3 tankers of oil were shipped to a refinery in Montreal or Europe every summer, for total production of 2.8 million barrels.Footnote 43

5.2 Reports prepared for the Five-Year Review

At the request of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, the Geological Survey of Canada prepared 2 reports on the oil and gas resources in the Eastern and Central Arctic. The first report "Resource Assessments of Northern Offshore Canadian Sedimentary Basins, 1973 to 2020"Footnote 44 (the Resource Assessment) covers all of the Canadian Arctic offshore, including the waters adjacent to Yukon and the Northwest Territories and areas of the Eastern and Central ArcticFootnote 45 subject to the moratorium. It presents brief descriptions of the geology of 8 sedimentary basinsFootnote 46,Footnote 47, the seismic surveys and drilling carried out, and the results of resource assessments of oil and gas in each basin.

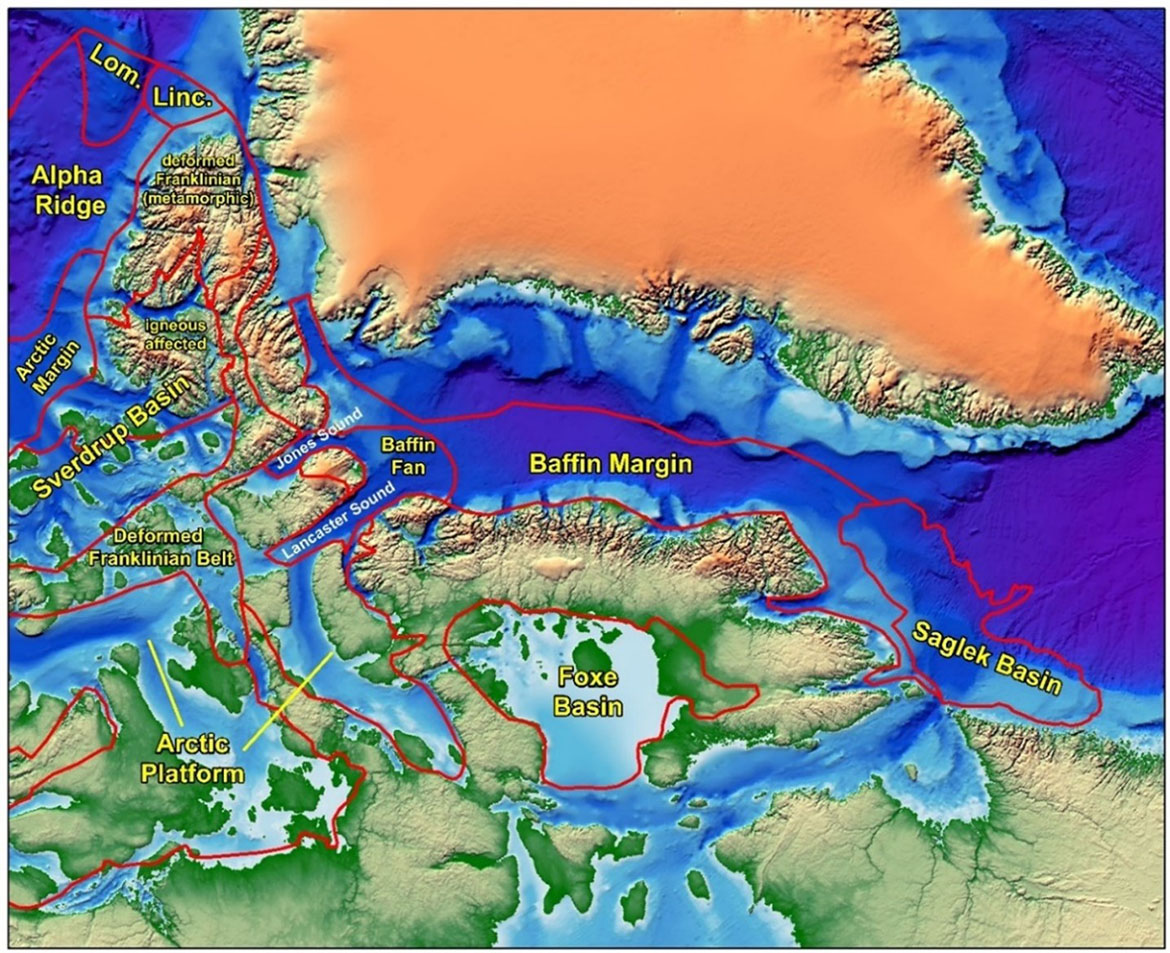

The second report, "Northern Nunavut Hydrocarbon Prospectivity Study"Footnote 48 (the Prospectivity Report), builds on the Resource Assessment to provide an overview of the prospectivityFootnote 49 of hydrocarbon resources in the offshoreFootnote 50 areas of the Eastern and Central ArcticFootnote 51, including 3 sedimentary basins not described in the first report. For each of the 10 basins that have at least some probability of containing hydrocarbons (Figure 5), the report describes several aspects related to the prospectivity, including the geology and petroleum systemsFootnote 52, past exploration, previous studies, previous resource estimates, the level of confidence in previous estimates, and future work that might be done with respect to the basins and the level of effort that would be required to do that work. The basins described in the report can be grouped into 3 areas:

Baffin Bay and Davis Strait

- Saglek Basin lies offshore Baffin Island, south of Cumberland Sound and extending along the coast of Labrador as far south as about 56°N.

- Baffin MarginFootnote 53 is present along the coast of Baffin Island extending south as far as Cumberland Sound. It includes a number of sub-basins.

- Lancaster Sound, Baffin FanFootnote 54 occupies Lancaster Sound and the adjacent area of Baffin Bay.

Source: Prospectivity Study; dashed lines and stars have been added – note that the locations of these are approximate.

Text alternative for Figure 5: Sedimentary Basins in Nunavut

Figure 5 is a depiction of sedimentary basins in Nunavut. A portion of the boundary (approximate) between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories is shown by the dashed line (the north-south portion follows the 110⁰W line of longitude.). The Drake and Hecla gas fields are shown by stars near the left margin, near the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, (Hecla is on the left) and the Hekja field is shown by the star below the "S" of Saglek Basin. The various areas depicted on the map are the following: the Deformed Franklinian Belt, which extends from Ellesmere Island to Melville Island between the Arctic Platform to the south and the Sverdrup Basin to the north; the Sverdrup Basin, which underlies the northern and central parts of the Arctic Islands, north of the Deformed Franklinian Belt; the Arctic Margin, north of the Sverdrup Basin, extending from Banks Island to Ellesmere Island; the Baffin Fan occupies Lancaster Sound and the adjacent area of Baffin Bay; the Alpha Ridge, located north of the Arctic Margin; the Lincoln Sea Basin, located north of Greenland and the Arctic Islands; the Lomonosov Ridge located west of the Lincoln Sea Basin and north of the eastern portion of the Alpha Ridge; the Baffin Margin, located in between Baffin Island, Ellesmere Island, Devon Island and Greenland; the Foxe Basin, located between Baffin Island and Melville Peninsula; the Saglek Basin lies offshore Baffin Island, south of Cumberland Sound and extending along the coast of Labrador as far south as about 56°N, and the Arctic Platform that covers the southern Arctic Islands, parts of northern Baffin Island and extends onto the northern mainland.

Central Arctic and Arctic Islands

- Foxe Basin lies between Melville Peninsula and Baffin Island.

- Arctic Platform covers the southern Arctic Islands and parts of northern Baffin Island and extends onto the northern mainland.

- Deformed Franklinian Belt extends from Ellesmere Island to Melville Island between the Arctic Platform to the south and the Sverdrup Basin to the north.

- Sverdrup Basin underlies the northern and central parts of the Arctic Islands.

Basins underlying the Arctic Ocean

- Lincoln Sea lies offshore north of Greenland and Ellesmere Island.

- Arctic Margin faces the Arctic Ocean along the northwest side of the Arctic Islands.

- Lomonosov Ridge extends north of Ellesmere Island towards the North Pole.

5.3 Previous resource assessments

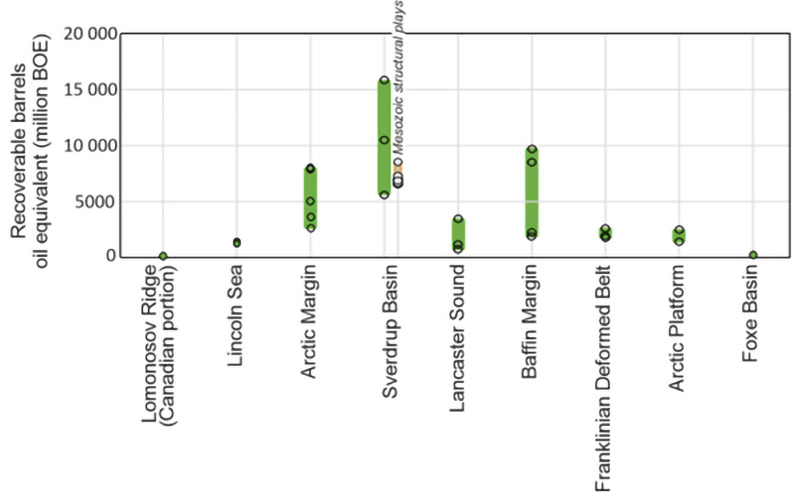

The previous resource assessments vary in quality and detail. According to the Prospectivity Report: "Older assessments predicted the size of the resource in a sedimentary basin, but did not predict where those resources might be found. Newer assessments from the Geological Survey of Canada make qualitative predictions on the location of resources but not their size." Figure 6 shows that on the basis of the previous assessments, most of the potential oil and gas resources are in the Sverdrup Basin, Baffin Margin and Arctic Margin.

Notes: Assessments for some basins include areas that are west of 110°W, thus are in the Northwest Territories. Assessments for Sverdrup Basin, Deformed Franklinian Belt and Arctic Platform include significant onshore resources. Baffin Margin excludes the Saglek Basin and the Baffin Fan. There are no separate previous assessments for Saglek Basin and Baffin Fan. "Barrels oil equivalent" (BOE) includes oil and gas; one barrel of oil is deemed to have the same amount of energy content as 6,000 cubic feet of gas.

Text alternative for Figure 6. Range of mean estimates of recoverable BOE from existing resource assessments of sedimentary basins of the Eastern and Central Arctic.

Figure 6 is a bar graph illustrating the range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent from existing resource assessments of the 9 sedimentary basins located in Central and Eastern Arctic that have at least some probability of containing hydrocarbons. The bar graph shows that the Canadian portion of the Lomonosov ridge contains none or few recoverable barrels of oil equivalent. The Lincoln Sea Basin as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of 1,000 to 2,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The Arctic Margin as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 3,000 to 8,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The Sverdrup Basin as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 5,000 to 16,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. Lancaster Sound as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 1,000 to 4,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The Baffin Margin as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 3,000 to 10,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The Franklinian Deformed Belt as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 2,000 to 3,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The Arctic Platform as approximately a range of mean estimates of recoverable barrels of oil equivalent of 2,000 to 3,000 million barrels of oil equivalent. The bar graph shows that Foxe Basin contains none or few recoverable barrels oil equivalent.

5.4 Hydrocarbon potential

The Prospectivity Report identifies 6 areas considered to have the highest potential for large oil or gas resources. All are "underlain by relatively young sediments and either have discoveries or geological conditions that are considered favourable for hydrocarbon accumulations." The 2 basins with at least 1 discovery are the Sverdrup Basin in the central Arctic Islands between Melville and Ellef Ringnes islands and the Saglek Basin off southeastern Baffin Island.

Other areas with high potential include:

- the Baffin Margin between Cumberland Sound and Lancaster Sound

- Lancaster Sound and the Baffin Fan at the mouth of Lancaster Sound

- the rifted Arctic Margin along the northwest side of the Arctic Islands

- the Lincoln Sea north of Ellesmere Island

All these areas are discussed in the following sections; the descriptions are based closely on the Prospectivity Study.Footnote 55

Four areas are considered to have lower hydrocarbon potential. The Foxe Basin was not buried deeply and lacks prolific source rocks needed to generate oil and gas.Footnote 56 Hydrocarbon generation in the Arctic Platform and Deformed Franklinian Belt would have occurred a long time ago and subsequent tectonic events have likely reduced the potential for preserved hydrocarbon pools. Because the Lomonosov Ridge has also seen major tectonic events, uplift and erosion, there is a reduced chance that significant hydrocarbon pools remain. These areas are not discussed further. Annex 6 shows the areas with high, medium and low hydrocarbon potential.

5.5 The Sverdrup Basin

Measuring about 1,300 kilometres along a northeast-southwest axis by up to 400 kilometres wide, the Sverdrup Basin is one of Canada's largest petroliferous basins. It encompasses a sequence of sedimentary rocks up to 13 kilometres thick. Although most of the basin lies within Nunavut, a small part at the western end, which holds 20 percent of the resourcesFootnote 57, is in the Northwest Territories. Most of the basin is well explored, however, undiscovered potential remains deeper in the basin.Footnote 58 Twenty-nine percent of the total resources of the basin are onshore and not subject to the moratorium.

Most of the 19 oil and gas discoveries are in a belt stretching from southwestern Ellef Ringnes Island to the Sabine Peninsula on Melville Island (see Figure 3 and the top figure of Annex 3). The discoveries include 2 of the largest undeveloped conventional gas fields in Canada, the Drake field on the east side of the Sabine Peninsula (with half of the resources onshore) and the Hecla field on the west side within the Northwest Territories. These fields hold approximately half of the discovered gas in the Sverdrup Basin, with an estimated 6 to 10 Tcf of recoverable gas.Footnote 59 There are also smaller gas fields to the north and northeast.

The Cisco oil field, just west of Lougheed Island, is the largest oil field discovered in the Arctic Islands, with an estimated 584 million barrels of oil.

5.5.1 Proposal to develop the Drake Gas Field

Panarctic Oils Ltd., the discoverer of the field, conducted a trial gas flow test during the 1970s with a subsea pipeline connecting a production well to shore where the gas was flared. In the mid-1970s, Panarctic proposed the Arctic Pilot Project including a gathering system at the field connecting all the production wells, a pipeline to Bridport Inlet on the south shore of Melville Island and processing facilities there to produce liquefied natural gas to be sent by ship to southern Canada. During the planning and regulatory review phases in the 1980s, cost estimates soared and gas prices fell, resulting in the cancellation of the project. Any new proposal to develop the Drake gas field would likely include production from Hecla and 1 or more of the smaller fields. The Arctic Pilot Project estimated that the Hecla and Drake fields together could produce gas quantities capable of heating 75,000 homes for 25 years.

5.6 The Saglek Basin

Previous resource assessments did not include a stand-alone assessment of the Saglek Basin. However, work done by the Geological Survey of Canada in the last decade provides insights into the resource potential of the basin. Jauer et al. (2014) interpreted a high potential fairwayFootnote 60 in the area in which the Hekja and Ralegh wells were drilled. They estimated that the Gudrid structureFootnote 61 to the east of the Ralegh N-18 well "could potentially contain ten times as much petroleum as found in the Hekja O-71 discovery based on the estimated size of the closure."Footnote 62 If so, this would be a world class deposit containing up to 23 Tcf of gas.

In the Prospectivity Report, Dewing et al. had a different interpretation. They stated that the "estimate of a field ten times the size of Hekja seems overly optimistic" and "would be at the very upper end of what might be expected" in that geologic setting. They further noted that "untested targets are likely to be in the size range of other discoveries along the eastern Canadian margin" which range from 2.2 to 2.7 Tcf of gas. One or more such fields in the Gudrid structure combined with the 2.3 Tcf of gas at Hekja would be a substantial resource that may be large enough to warrant development.

Further work is required to resolve the uncertainty and clarify the potential gas resources in the Gudrid structure as well as other settings in the Saglek Basin. The Prospectivity Report described work that could be done, including reprocessing the older vintage seismic from the original field tapes and carrying out new high quality seismic surveys using longer streamers and with sound sources tuned for better penetration.Footnote 63 Other work could include:

- new age dating of cuttings samples from drill holes

- more detailed seafloor imaging

- sampling seeps, either from the surface or at the seafloor

- low temperature thermochronology studies

Follow-up drilling would ultimately be necessary to determine whether significant quantities of gas are present.

5.7 Areas with high potential but which are untested by drilling

5.7.1 Baffin Margin

Baffin Margin occupies that part of Baffin Bay and Davis Strait between Baffin Fan and Saglek Basin. A narrow strip adjacent to the coast of Baffin Island, the Baffin Shelf, is the most prospective part of the Baffin Margin. Although the best potential appears to be in the north, where the Scott Inlet oil seeps demonstrate an active petroleum system, the recent discovery of new basins and sub-basins to the south coupled with new geological interpretations suggests that new assessments of the geological potential of the entire Baffin Margin are needed.

5.7.2 Lancaster Sound: Baffin Fan

Lancaster Basin and that part of Baffin Fan immediately adjacent to it and extending to the north past Coburg Island and to the south nearly to Scott Inlet are assessed as having moderately high to very high hydrocarbon potential (Atkinson et al.).Footnote 64 This assessment is based in part on an earlier report by Harrison et al. that identified 40 structural targets in a "belt of prospects" within the same area, 12 of which "may contain hydrocarbons in significant quantity". Much of the high potential area is within the proposed Tallurutiup Imanga, Lancaster Sound National Marine Conservation AreaFootnote 65, where oil and gas activities would not be permitted. However, a significant part of the belt adjacent to Coburg Island that lies outside the Conservation Area may include some of the high-quality targets.

5.7.3 Arctic Margin and Lincoln Sea

The rifted Arctic Margin and Lincoln Sea along the northwest side of the Arctic Islands are in an area in which very little is known of the geology of the sedimentary basins and the resource potential can currently be estimated only by comparison with areas of similar geology elsewhere in the world. While evidence suggests there is potential for considerable hydrocarbon resources, exploration to discover these resources would be extremely difficult due to the remote location and extensive ice cover. Furthermore, all of the areas under the Arctic Ocean adjacent to the Arctic Islands are within the interim boundaries of Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area in which development activities are currently prohibited and could be permanently prohibited if a conservation area is established in the region.

5.8 Summary

The Prospectivity Report summarizes the potential of several sedimentary basins and the need for further work and new resource assessments. These basins have the potential to host significant hydrocarbon resources, with estimates of discovered and undiscovered resources ranging up to 15,869 million barrels of oil equivalent for the Sverdrup Basin. The development of these resources could yield important revenue for Nunavut once a co-management regime is in place for the region and a revenue sharing agreement is established between the territory and the Government of Canada.

Although the Sverdrup Basin has the highest potential to host significant hydrocarbon resources, "there have been major advances in geological knowledge in the eastern Arctic (Saglek Basin, Baffin Margin, Baffin Fan) since the last hydrocarbon resource assessments were done in those areas. New hydrocarbon resource assessments in the Eastern Arctic would incorporate new knowledge about the Baffin Fan and Saglek Basin, and would revise the estimates of resource potential in these areas."

On the basis of information in the Prospectivity Report, it is the opinion of the committee that new studies and resource assessments in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait should be done as soon as possible. Priority should be given to further work to resolve questions related to the potential gas resources in the part of the Saglek Basin east of the Hekja field. The demonstration of the potential for significant resources could lead to the preparation of detailed development scenarios. The committee also views the Drake gas field as a priority for future work.

6. Proposal for scenarios for the Sverdrup and Saglek Basins

This section presents an outline for 2 high-level hypothetical scenarios for natural gas projects for consideration as part of potential further work to be done. Future scenarios could also be carried out for the development of offshore oil fields such as the Cisco field in the Sverdrup Basin. The committee will decide on exactly which scenarios are to be developed through a collaborative workplan.

Scenarios should be developed for:

- the exploration for and production of gas from the Saglek Basin and Baffin shelf

- the exploration for and production of gas in the Sverdrup Basin

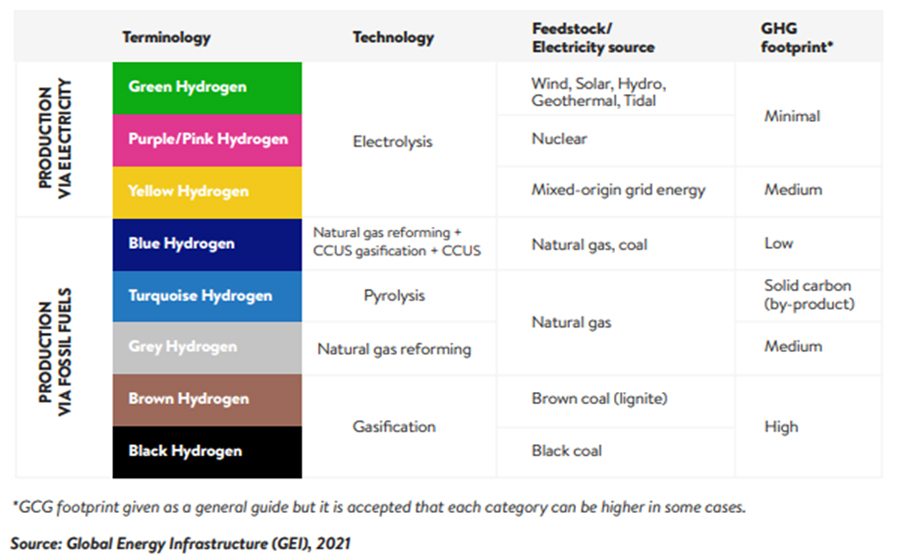

- the processing of gas from those areas into liquefied natural gas or hydrogen and (or) hydrogen products

6.1 Sverdrup/Drake

Based on prior studies, the combined fields of Drake and Hecla (in the Northwest Territories) and a few other nearby fields in the Sverdrup Basin have significant resources of gas that may warrant production. Proposals were made in previous decades to transmit the gas from these fields, which include both onshore and offshore portions, by pipeline to Bridport Inlet on the south shore of Melville Island where it would be processed into liquefied natural gas and sent to markets in specialized ships.

6.2 Saglek/Hekja

There is a gas resource subject to a significant discovery licence at the Hekja field in southern Davis Strait off Frobisher Bay. The Geological Survey of Canada has indicated that a structure to the east of Hekja may host much larger gas resources, but data on this is inconclusive. New seismic surveys and drilling would be required to determine whether resources exist. If resources are present in economic amounts, gas could be produced from Hekja and the nearby area and transmitted by subsea pipeline to a plant on Loks Land (Island) or the nearby Baffin Island mainland for processing into liquefied natural gas. The liquefied natural gas would be sent to markets in specialized ships.

6.3 Low-carbon methods to produce liquefied natural gas or hydrogen

Producing gas and converting it to liquefied natural gas could involve the use of electricity from renewable energy sources or small modular nuclear reactors, the capture and storage of the carbon emissions or a combination of these approaches. An integrated approach of this type may be necessary to meet government climate policy requirements at the time of development.Footnote 66

Another option not previously proposed for production in these basins would be to convert the gas into hydrogen through a process called reforming or by a different chemical process. The hydrogen gas would be liquefied or converted into a solid compound (for example a hydride) or other product such as ammonia and shipped to markets. The advantage of producing hydrogen is that the product of its combustion is water, little or no greenhouse gases would be emitted. Both the production of hydrogen using the techniques described above and the ultimate use of the hydrogen may be consistent with Canada's net-zero emissions requirement.

6.4 Potential timeline for development

When considering the possibility of future development, it is necessary to understand when this development might occur and the economic and climate conditions that might prevail at that time.

In a report prepared for the Strategic Environmental Assessment, Nunami StantecFootnote 67 estimated that the "full life cycle of a hypothetical oil and gas project in Davis Strait or Baffin Bay could be in the range of 45 to 80 years from the start of seismic exploration, through exploration drilling to production and eventual decommissioning." That part of the process beginning with the first call for nominations up to the point the first gas is produced could take 30 to 35 years.

6.5 Potential benefits from natural gas

The Government of Nunavut is the largest public sector employer in the territory. The mineral exploration and mining sector, which employs over 900 Nunavummiut yearly, is the largest industry. Fishing, sealing, and tourism are growing sectors of the economy that also bring important sources of income for Nunavummiut.Footnote 68

The energy industry, if managed properly, can bring revenue and spark local economic development. Natural gas development creates the potential for new funding and investment in the region, contributing to overall increases in institutional capacity. The industry could also bring training and employment opportunities for Nunavut communities, local infrastructure investments, and the development of emergency response capacity. Energy projects that use natural gas are also better for the environment than those using coal or oil.

Another benefit of natural gas development could be energy security, reducing dependence on imported diesel while lowering energy costs. This is important for communities that are isolated and have very few options for affordable heat and power. While no natural gas project has occurred in Nunavut, ongoing initiatives in other jurisdictions show advancement in domestic energy security in addition to generating permanent jobs for residents and cost savings in fuel and heating. For example, the experiences in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region have highlighted the social and economic benefits of producing energy within the region. The Inuvialuit Petroleum Corporation has plans to develop a previously discovered natural gas well on the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula and process it into liquefied natural gas for distribution to Inuvialuit communities in a project known as the Inuvialuit Energy Security Project.Footnote 69 This ongoing initiative could advance domestic energy security in addition to generating revenues from global market exports.

6.6 Information required

Work to determine if production from Saglek Basin, Baffin Shelf and the Sverdrup Basin might be viable would include, but not be limited to, the following:

- The studies and other work described in the Prospectivity Study to show whether there is good potential for additional gas resources:

- in the Saglek Basin, especially in the vicinity of the Hekja field

- on the Baffin Shelf to the north of Hekja

- Updating of resource assessments for all of Nunavut.

- An analysis to show whether the technology that could be used to produce and process gas in accordance with the scenarios and the Government of Canada climate change policy requirements. Such technology could potentially include:

- renewable energy sources to produce electricity for operations

- small modular nuclear reactors to produce electricity for operations

- carbon capture and storage to capture any greenhouse gas(es) (GHG) emitted (if gas is used to provide the power for production and processing)

- An analysis of the potential demand for the liquefied natural gas, hydrogen or other products described in the scenarios and an analysis of economic factors of potential projects.

- An analysis of the potential benefits of the project to Nunavummiut and other Canadians, including royalties, benefit plans and (or) socio-economic agreements, fees and rents for use of Inuit Owned Lands (for onshore operations), and employment and business opportunities.

- Reports from consultations and other sources that show that such a project is socially and culturally acceptable.

- An overview of socio-economic impacts and benefits from other northern producing regions:

- Northwest Territories

- Newfoundland

- Norway

- Alaska

- Russia

In addition to the requirements in this list, consultations with officials from the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and the Government of the Northwest Territories would need to be held with respect to the possibility of developing the Hecla gas field in conjunction with the Drake operation.

7. Summary

Regulatory framework

All oil and gas activities in Canada's offshore are subject to a rigorous environmental and regulatory regime. Canada has recently modernized its regime to ensure that local and indigenous participation are fully part of the impact assessment process. Other modernization aspects included strengthening safety requirements for the oil and gas industry and mandating the evaluation of impacts projects could have on climate policy requirements.

The Nunavut Agreement sets the foundation for Inuit participation in "decision-making concerning the use, management and conservation of land, water and resources, including the offshore". Many of the provisions that relate to the management of resource development in the Nunavut Settlement Area are enshrined in 2 federal acts which set out the powers, functions, objectives, and duties of the Institutions of Public Government. The Nunavut Planning and Project Assessment Act is particularly relevant to oil and gas development as it formally establishes the regulatory processes through which project proposals requiring authorization are reviewed in respect of land use conformity and environmental impact assessment.

A benefits plan, including provisions for local training and employment, is required for any offshore oil and gas project proposal. Further, under the Canada Petroleum Resources Act, any royalties from an oil and gas offshore development project would flow to the Government of Canada, with a percentage paid to Inuit for a project in the Nunavut Settlement Area or the Outer Land Fast Ice Zone. However, after a Devolution Agreement has been signed, Nunavut would be the beneficiary of royalties from onshore projects. An offshore agreement would have the potential to add royalties for Nunavut that could be invested in territorial needs such as housing, health, education and infrastructure development.

Climate change commitments

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement, the Government of Canada has made significant commitments in its fight against climate change. The initial measures were set out in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, followed by a strengthened climate plan in 2020. The Prime Minister announced on April 22, 2021, that Canada's greenhouse gas emissions target under the Paris Agreement is 40 to 45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Subsequently, the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, which formalizes Canada's target of net-zero emissions by 2050, became law. Since that time, the Government of Canada has made further commitments, including some relating specifically to the oil and gas sector. These include capping greenhouse gas emissions from the sector at current levels and reducing them at a pace and scale needed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. As well as joining the Global Methane Pledge and committing to reduce oil and gas sector methane emissions by at least 75 percent below 2012 levels by 2030.

Strategic environmental assessment for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait

From 2017 to 2019, the Nunavut Impact Review Board carried out a Strategic Environmental Assessment for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait looking at potential impacts and benefits that offshore oil and gas development could have on the region. This work included the participation of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, and the Government of Nunavut as well as 3 rounds of consultations with the communities of the Qikiqtani Region that could be impacted by development. The Nunavut Impact Review Board's final report highlights knowledge gaps and work required to ensure the appropriate balance between environmental stewardship and economic development for Nunavut.

In its final Strategic Environmental Assessment report, the Nunavut Impact Review Board shared 79 recommendations and concluded that the moratorium should remain in place for Baffin Bay and Davis Strait until the key issues set out in the report can be addressed, a process expected to take at least 10 years. The Government of Nunavut developed a draft "Action Plan Discussion Paper" to address the Nunavut Impact Review Board's report and recommendations and to categorize and prioritize action items. Although the Strategic Environmental Assessment dealt only with the effects of oil and gas development in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait, some of the findings and recommendations may be applicable to other parts of the Eastern and Central Arctic.

Hydrocarbon potential and basin prospectivity

At the request of the committee, the Geological Survey of Canada wrote 2 reports on potential oil and gas resources in the Eastern and Central Arctic. The report on the "Northern Nunavut Hydrocarbon Prospectivity Study" assessed the potential of ten sedimentary basins. It concluded that:

- 4 of the basins were unlikely to have significant resources

- 4 have good potential on the basis of what is known of their geology but have not been tested by drilling

- 2 basins, the Sverdrup and the Saglek Basins, have good potential as indicated by discovered resources

There are 19 discovered oil and (or) gas fields in the Sverdrup Basin and 1 gas field in the Saglek Basin. The report described work that could be useful in further assessing the potential in the Saglek Basin near the area of the Hekja gas field and in the Baffin Margin to the north. Drilling would ultimately be required to confirm whether more resources are present.

Proposal for scenarios for the Sverdrup and Saglek Basins

Detailed scenarios should be developed for:

- the exploration for and production of gas from the Saglek Basin and Baffin shelf

- the exploration for and production of oil and gas in the Sverdrup Basin

- the processing of gas from those areas into liquefied natural gas or hydrogen (including products made from hydrogen)

Producing gas and converting it to liquefied natural gas could involve the use of electricity from renewable energy sources or small modular nuclear reactors, the capture and storage of the carbon emissions or a combination of these approaches. The conversion of the gas into hydrogen, an option not previously proposed for production from these basins, would be done through a process called reforming or by a different chemical process. An integrated approach of this type may be necessary to meet government climate policy requirements at the time of development. The exact scenarios to be developed are subject to future discussion and decisions amongst partners and stakeholders.

Future projects could generate institutional capacity, infrastructure, and employment in the territory in the coming years. Local energy projects have the potential to create new investment opportunities in the region and to meet local energy demands.

8. Conclusion

In this report, the committee has outlined the regulatory framework for oil and gas development in the Eastern and Central Arctic, including the various ways in which Nunavummiut can benefit from exploration and production, particularly within the Nunavut Settlement Area. The committee also identified the areas with the highest resource potential, namely the Sverdrup Basin and Saglek Basin, and proposed follow-up studies, including the development of detailed scenarios, to determine how development could be beneficial to Nunavut communities and whether operations could be done safely and in accordance with Canada's climate change commitments.

The committee recognizes the key findings of the Nunavut Impact Review Board's Strategic Environmental Assessment and that significant work remains to be done in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait and other areas throughout Nunavut to fill existing knowledge gaps. The committee acknowledges that more collaborative work is desirable, and recommends the development of a joint workplan for future work regardless of the final decision on the moratorium.

The importance of community engagement cannot be overstated. Governments, Inuit, and industry are encouraged to continue to work together to address knowledge gaps with respect to offshore oil and gas development in Nunavut.

References

Bailey, 1983. The Arctic Pilot Project, Petro-Canada Energy Exploration & Exploitation; Graham & Trotman Ltd., Vol. 2 No.1.

Dewing, K.E., and Kung, L.E., 2020. Resource Assessments of Northern Offshore Canadian Sedimentary Basins, 1973-2020; Geological Survey of Canada, Internal Report, 76p.

Dewing, K.E., C.J. Lister, L.E. Kung, H.M. King and E.A. Atkinson., 2021. Offshore Nunavut Hydrocarbon Prospectivity Study; Geological Survey of Canada, Internal Report, 46 p.

Harrison, C., Brent, T.A. and Oakey, G.N., 2010. Baffin Fan and its inverted rift system of Arctic eastern Canada; is this another Beaufort-Mackenzie Basin?; GeoCanada 2010.

Harrison, R.J., 2016. Review of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act submitted by the Minister's Special Representative.

Intecsea and Vysus Group, 2021. Survey of Arctic Well Control and Containment Equipment, Best Available Technologies, and Practices.

Jauer, C.D., Oakey, G.N., Avery, M., Williams, G. and Wielens, J.B.W.H., 2014. The Saglek Basin in the Labrador Sea: Past Exploration History, Current Estimates, and Future Opportunities; Search and Discovery Article #10587.

Jauer, C.D., Oakey, G.N., Williams, G. and Wielens, J.B.W.H., 2014. Saglek Basin in the Labrador Sea, east coast Canada; stratigraphy, structure and petroleum systems; Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology 62(4): 232-260.

Jauer, C.D., Oakey, G.N. and Qingmou Li, 2019. Western Davis Strait, a volcanic transform with petroliferous features; Marine and Petroleum Geology 107, 59-80.

Nunami Stantec, 2018a. Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait: Environmental Setting and Review of Potential Effects of Oil and Gas Activities. Nunami Stantec Limited.

Nunami Stantec, 2018b. Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait: Oil and Gas Life Cycle Activities and Hypothetical Scenarios. Nunami Stantec Limited.

Nunavut Impact Review Board, 2019. Final Report for the Strategic Environmental Assessment in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait; Nunavut Impact Review Board File No. 17SN034.

Stantec Consulting Ltd., 2021. Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Oil and Gas Development in the Arctic; Canada's Climate Change Commitments and Global Impact; Prepared for Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

Annex 1: Additional details of the prohibition orderFootnote 70

On December 20, 2016, the Government of Canada announced, as part of the Joint Arctic Leaders Statement, an indefinite suspension on new oil and gas licences in Canada's Arctic waters (the Arctic offshore moratorium), to be reviewed every 5 years through a climate and science-based assessment. The moratorium acknowledges the important balance between the historic value of the Arctic waters for Northern Indigenous peoples and the value of establishing a strong, sustainable Arctic economy and ecosystem supported by science-based management. While the moratorium suspends the issuance of new oil and gas licences, it does not suspend oil and gas activities nor does it suspend the terms of the 11 affected active licence holders, exposing a gap in the regime and requiring a solution.

In 2017, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada officials consulted extensively with:

- territorial and Northern Indigenous stakeholders:

- governments of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

- Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated

- Regional Inuit Associations

- the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers

- the active oil and gas licence holders on their future interests in the Arctic offshore

In October 2018, Canada announced, in its Next Steps on Future Arctic Oil and Gas Development, that it would freeze the terms of the existing licences and to protect them from expiring for the duration of the moratorium. Next steps also included the co-development, with territorial and Northern Indigenous governments, of a framework for a science-based assessment every five years that accounts for marine and climate change science, and the negotiation of a Western Arctic offshore oil and gas co-management agreement with the governments of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation.

On July 30, 2019, the Governor in Council made the Order Prohibiting Certain Activities in Arctic Offshore Waters, pursuant to section 12(1) of the Canada Petroleum Resources Act, R.S.C. 1985. The order prohibited all oil and gas activities in the Arctic offshore and suspended the terms of all active oil and gas licences in the western and eastern Arctic offshore areas. This order was set to expire on December 31, 2021, in conjunction with Canada's consideration of the 5-year science-based review report and next steps for the moratorium. The reports were delayed due to federal and Nunavut election processes.

An exploration licence has a 9-year, fixed term in which a licence holder is required to complete the drilling of an exploration well. The extension of this order prevents the active licences from expiring while Canada considers the climate and marine-based assessment reports prepared in collaboration with the territories, Inuvialuit and Inuit organizations to inform next steps on the Arctic offshore moratorium.

The order will also allow Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada officials to continue to collaborate with Northern partners and to advance new climate and marine-based research in respect of meeting Canada's 2016 commitment to review the moratorium every 5 years.

Without extending the order, existing licences would have begun to expire after December 31, 2021. Canada would not have been able to meet the commitment to freeze the terms of existing licences to preserve existing rights, or to meet Canada's moratorium review commitment.

Objective

- To provide protection to active Arctic offshore licence holders for the duration of the moratorium, pending a decision by the Government of Canada on next steps.

- To complement the policy intent of the moratorium and to suspend further capital investment while providing protection to active licence holders and to preserve their rights.

- To respond to the interests of territorial governments and to respect the rights of Northern Indigenous peoples regarding future oil and gas and economic development potential in the offshore.

- To establish a path forward for the strategic management of Arctic offshore oil and gas in collaboration with partners.

Annex 2: Sovereignty and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

Defining Canada's extended continental shelf

Fisheries and Oceans Canadian Hydrographic Service, Natural Resources Canada's Geological Survey of Canada and Global Affairs Canada, with the support of the Canadian Coast Guard and other international partners, have worked for several years on a project to determine the outer limits of Canada's extended continental shelf, under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is an international treaty that sets out the legal framework for ocean activities. It defines the maritime zones along a country's coastline, and the rights and duties of a country regarding these zones. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea also recognizes that coastal states have sovereign rights over the natural resources of the seabed and subsoil of the continental shelf, as well as jurisdiction over certain activities like marine scientific research. It states that countries can extend their territory beyond 200 nautical miles if they can show that their continental shelf is a natural prolongation, or continuation, of its land territory. The continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles is known as "the extended continental shelf." An estimated 85 countries, including Canada, are thought to have an extended continental shelf.

In 2003, Canada embarked on a history-making project to define the outer limits of its continental shelf in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. In 2013, Canada filed a submission to the United Nations regarding its continental shelf in the Atlantic Ocean and preliminary information concerning the outer limits of its continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean. Canada is continuing to collect and analyze continental shelf data in the Arctic Ocean and is collaborating with neighbouring states in the scientific, technical and legal.

Annex 3: Rights disposition in the Central and Eastern Arctic

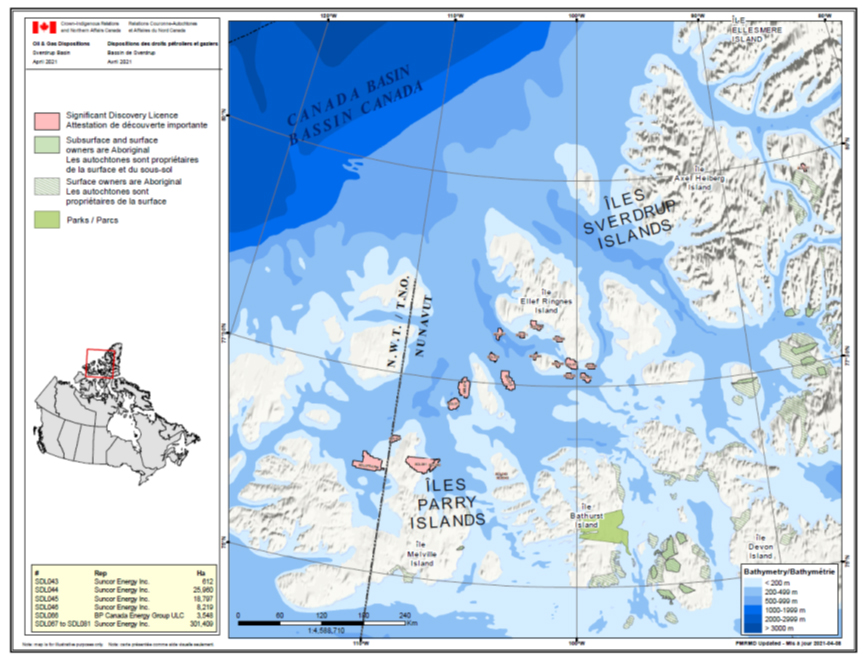

Note: The Drake gas field is covered by two significant discovery licences immediately north of the word "ILES". The Hecla field lies to the west of Drake.

Text alternative for this figure

The following figure is a map depicting oil and gas rights disposition in the Arctic Archipelago. Significant discovery licences are mainly located around and between the Parry Islands and Ellef Ringnes Island. There are 20 in total, all of them held by Suncor Energy Inc. except for SDL 066 which is held by BP Canada Energy Group ULC. The map also shows where Indigenous owned surface and subsurface lands are located in the Arctic Archipelago. The map also points to the location of the Polar Bear Pass (Nanuit Itillinga) National Wildlife Area located in the southern part of Bathurst Island. Part of the Canada Basin is also illustrated on the map. The boundary between the Northwest Territories and Nunavut is show on the map.

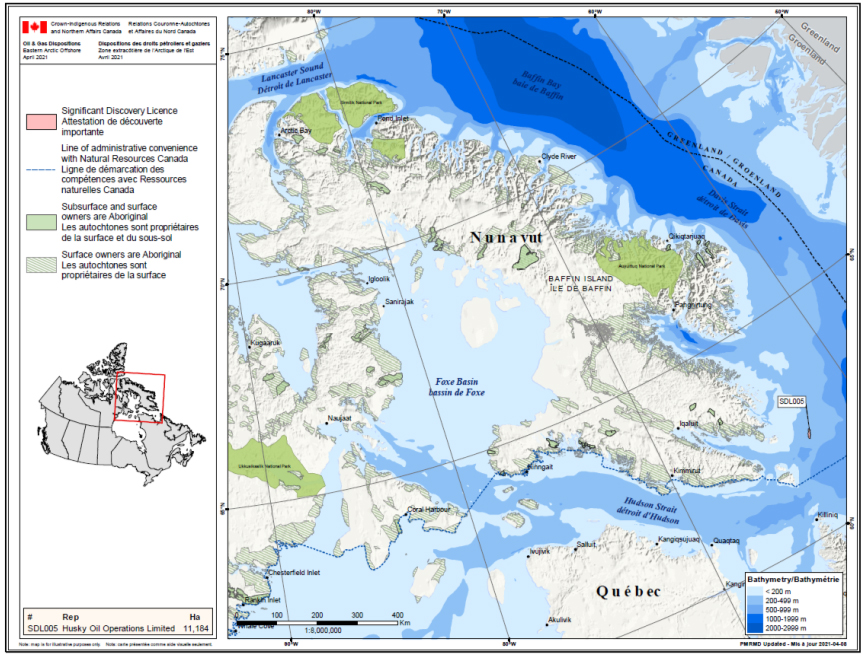

Note: The significant discovery licence in Davis Strait near the right margin of the figure covers the Hekja gas field.

Text alternative for this figure

The following figure is a map depicting oil and gas rights disposition in Eastern Arctic. The only significant discovery licence in this region is located east of Baffin Island and is owned by Husky Oil Operations Limited. The map also shows the line of administrative convenience with Natural Resources Canada which is located south of Baffin Island and extends from the Hudson Strait to Chesterfield Inlet. The map indicates where Indigenous owned surface and subsurface lands are located in the Eastern Arctic. National parks located in this region are also illustrated on the map, namely Auyuittuq National Park and Sirmilik National Park on Baffin Island, and Ukkusiksalik National Park located between Chesterfield Inlet and Naujaat. The map also shows the boundary between Canada and Greenland located in Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait.

Annex 4: Call cycle for oil and gas rightsFootnote 71

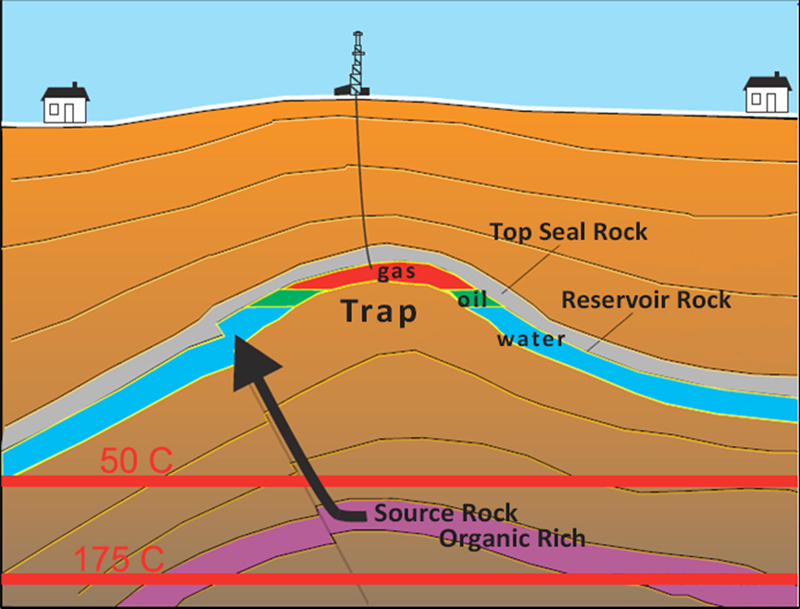

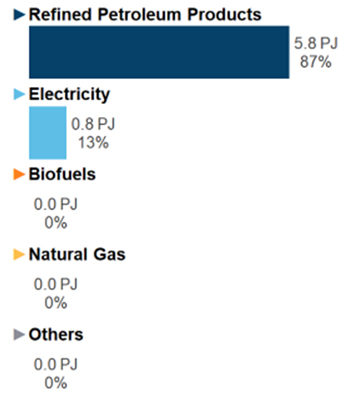

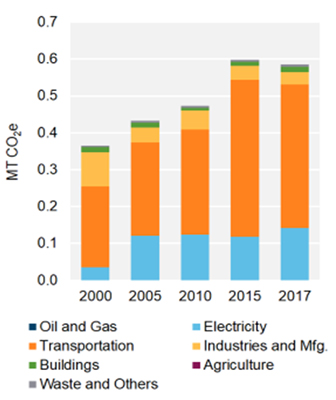

Text alternative for this figure