Evaluation of Engagement and Capacity Support

Prepared by: Evaluation Branch

December 2021

PDF Version (538 KB, 37 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| BOC: |

Basic Organizational Capacity |

|---|---|

| C&PD: |

Consultation and Policy Development |

| CIRNAC: |

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

| FICP: |

Federal Interlocutor’s Contribution Program |

| IRO: |

Indigenous Representative Organization |

| ISC: |

Indigenous Services Canada |

| MNC: |

Métis National Council |

| NIO: |

National Indigenous Organization |

Executive Summary

The following provides a snapshot of the key elements of the Evaluation of Engagement and Capacity Support. The report examines the following three funding authorities managed by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) with the support of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC):

- Basic Organizational Capacity (BOC):

- Provides funding to eligible Indigenous Representative Organizations (IROs) to support political advocacy, membership liaison and policy development.

- Consultation and Policy Development (C&PD):

- Funds activities that investigate, develop, propose, review, inform or consult on policy matters within the mandate of the Department.

- Federal Interlocutor's Contribution Program (FICP):

- Aims to enhance the capacity, stability, and accountability of both Métis and Non‑Status and other off-reserve IROs to represent their members, and to build partnerships with federal and provincial governments and the private sector.

The evaluation incorporated the following lines of evidence:

- Literature review

- Program document review

- Financial data analysis

- Key informant interviews

This report examines the performance (efficiency and effectiveness) and relevance of each authority, and the relationships between these authorities.

Evaluation Findings

Performance: Impacts on Outcomes

- BOC funding is not fully attaining the intended outcome of IRO contributions to and participation in government policy and program development in a meaningful and equitable manner.

- The Performance Information Profile for the BOC authority does not include relevant indicators for tracking the impact of program expenditures on expected outcomes.

- BOC funding does not take into account the broader mandates of IROs, which contribute to their ability to meaningfully participate in government policy and program development.

- Engagement of IROs increased during the period of evaluation for the development of government policy and programs; however, IROs routinely expressed that engagements were not conducted meaningfully or resourced adequately.

- The Performance Information Profile for the C&PD authority does not include relevant indicators for tracking the impact of program expenditures on expected outcomes.

- There is overlap and a lack of clarity between the three authorities: BOC, C&PD, and FICP. The C&PD authority is regularly viewed and used by departmental officials and recipient IROs as a 'top up' for insufficient core capacity (BOC) funding.

- There is evidence that the FICP Governance Stream is contributing to intended outcomes, including the development and maintenance of an objectively verifiable membership system for Métis in Canada.

- The intended outcomes theory of change for the FICP Projects Stream is unclear and funded projects do not correspond with intended outcomes and lack strategic direction.

- There is lack of clarity from CIRNAC on how to proceed with Métis and Non-Status Indian partners following the Supreme Court of Canada's Daniels decision.

- There is a lack of negotiated, multiyear funding agreements with national organizations representing women and Non-Status Indians.

Performance: Efficiencies

- It is not efficient use of the Department's and IROs resources and time, to require the application, approval, and preparation of several separate funding agreements, and delivery thereof, with the same recipients in a given year.

- Delays in the delivery of committed funds to IROs are detrimental to the effective and efficient use of funds by organizations and undermine the positive achievements made by Canada to renew the relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Relevance: Alignment of Current Approach with Self-Determination and a Renewed Relationship

- Aside from gains (positive support to governing members and their membership systems made under the FICP Governance Program), the Department's approach to IRO support is limited in its contribution to higher level government priorities of advancing Indigenous self-determination and renewing the relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Evaluation Recommendations

It is recommended that CIRNAC:

- Work with its Indigenous and federal partners to:

- define the core operational capacity requirements for recipient organizations to meaningfully and equally contribute to government policy and program development; and

- consider options for a more flexible, multiyear, comprehensive funding formula for core operational support that enables meaningful participation in government policy and program development, as well as the broader aim to support self-determination and advancement of Indigenous governance institutions.

- Improve the coordination and alignment of the three authorities with the goal of reducing the overlap, and to ensure better coordination of funding.

- Work with its Indigenous and federal partners to develop a strategy for the FICP Projects Stream that addresses the Supreme Court of Canada's 2016 Daniels decisions re: Section 91 (24) rights, and supports the self‑determination and advancement of Indigenous governance institutions.

- Work with its Indigenous and federal partners to develop an engagement model that facilitates meaningful Indigenous input and participation in policy and program development as it relates to theses authorities. The model should include a clear directive with guidance tools to ensure a coordinated and uniform approach by departmental officials to reduce engagement fatigue amongst Indigenous partners.

- Work with its Indigenous and federal partners to develop new performance measurement tools for core operational capacity support, departmental engagement efforts, and the new approach to the relationship with Section 91(24) Métis and Non-Status Indian groups that are meaningful and beneficial to both CIRNAC and recipients.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of Engagement and Capacity Support

1. Management Response (Overview)

It is important to recall that this was an unique evaluation of three separate but related contribution authorities (Basic Organizational Capacity, Federal Interlocutor's Contribution Program, and Consultation and Policy Development), the grouping of which came at the request of the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Policy and Strategic Direction (PSD). This was done in order to provide measured guidance on an enhanced coordinated approach to the funding of organizations, including Indigenous Representative Organizations (IROs), and engagement with a goal of broader transformative change. This request also acknowledges the need to address a patchwork of legacy programs created for separate purposes at different points in time that are in need of streamlining/modernizing to ensure they work better together for the best possible outcomes.

The evaluation provides guidance to better situate the three evaluated programs to make informed transformative decisions by focusing on the relationship between the three authorities and the need for greater coordination and alignment amongst them. This need is reflected in Recommendation #2, which calls on PSD to "improve the coordination and alignment of the three authorities with the goal of reducing the overlap, and to ensure better coordination of funding." We agree that clarification/updating of the distinct policy intentions and objectives of core capacity funding, in particular, is needed to ensure that all recipient organizations have an opportunity to provide meaningful contributions to government policy and program development. We also see a need for further consideration of "options for a more flexible, multiyear, comprehensive funding formula for core operational support" (Recommendation #1), and will undertake this action.

We concur with the findings of this report – many of which were shared as existing challenges at the outset of the evaluation period launched in Fall 2018. However, there are significant challenges in the correlation of responsibility for relationship outcomes (and performance measurement thereof) with capacity and/or engagement funding authorities themselves. As departmental stewards of three Treasury Board authorities, we agree that "clear directive and guidance tools to ensure a coordinated and uniform approach by departmental officials to reduce engagement fatigue amongst Indigenous partners" (Recommendation #4) are necessary. The Department is currently taking steps to improve coordination of engagement on and in the Department's policy development activities. For example, the Departmental integrated planning and reporting process includes tracking policy development and engagement activities supported by the Department. Importantly, this work does not coordinate or track Indigenous engagement activities on a whole-of-government level. Whole-of-government coordination and tracking mechanisms would exceed the existing mandates of any one department and require significant resources dedicated to this task. However, the Department, through its Implementation Sector, will be leading work to develop a strategy to improve Crown consultations, engagement and co-development with Indigenous peoples on a whole-of-government basis.

The steps identified in the Action Plan below to address each recommendation will take time, as transformative change of Basic Organizational Capacity (BOC) funding must be incremental in approach due to the very same mandate commitments of co-development and meaningful engagement of Indigenous partners and recipients outlined in the evaluation report's recommendations. To this end, PSD will undertake a full program review of the funding relationship with organizations, including IROs, to determine how best to:

- coordinate the three programs evaluated (as well as others in other sectors, including Treaties and Aboriginal Governance and Indigenous Services Canada – Regional Operations);

- coordinate capacity support and engagement efforts; and,

- "develop new performance measurement tools for core operational capacity support, departmental engagement efforts, and the new approach to the relationship with Section 91(24) Métis and Non-Status Indian groups that are meaningful and beneficial to both CIRNAC and recipients (Recommendation #5)."

The Federal Interlocutor's Contribution Program (FICP) is a complex construct of governance, policy development, project and more recently Métis Nation housing funding that is intended to improve the relationship between the Government of Canada and Métis and Non-Status Indian representative organizations with the aim of closing socio-economic gaps. The Métis Nation Housing stream was added after the evaluation, so it was not included and its objective is outside the principal objective of the authority. Further, the evaluation initially conflated the Métis Governance Stream and its intent with the overall program authority. While this has been addressed in the evaluation, it creates a situation where the Projects Stream received less focus in the evaluation itself. PSD will work to revise the Terms and Conditions of the program to clearly articulate each of the streams and build stronger links between the Supreme Court of Canada's 2016 Daniels Decision. PSD will ensure that these revisions are informed by complementary work being done to assess current policy approaches to Métis and Non-Status Indians and to establish a Post-Daniels Reconciliation strategy.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

1. CIRNAC should work with Indigenous and federal partners to: a) define the core operational capacity requirements for recipient organizations to meaningfully and equally contribute to government policy and program development; and, |

a) Agree. Officials from CIRNAC and ISC responsibility centres will convene discussions with all concerned parties to clarify the policy intentions (and need for updating thereof) of the BOC program with respect to the core capacity requirements of Indigenous Representative Organizations, and to better align with FICP and C&PD and their implementation within PSD. | Director General of Indigenous and External Relations Branch, Policy and Strategic Direction | Start Date: |

b) consider options for a more flexible, multiyear, comprehensive funding formula for core operational support that enables meaningful participation in government policy and program development, as well as the broader aim to support self-determination and advancement of Indigenous governance institutions. |

b) Multiyear funding agreements are already in place for many recipients of BOC, FICP and C&PD, and are an available option to all eligible recipients. Discussions are currently being led by PSD and Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Office with partner Organizations, including IROs and federal stakeholders, as to the viability of a more flexible and comprehensive approach to organizational funding (core and project). |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy and Strategic Direction/Chief Financial Office |

Completion Date: March 31, 2023 |

| 2. CIRNAC should improve the coordination and alignment of the three authorities with the goal of reducing the overlap, and to ensure better coordination of funding. | Agree. Clarification of policy intentions in the are of core/governance support provided through BOC and FICP (including definition of key terms, formula for funding levels, eligibility, and greater understanding of recipient IRO mandates) is necessary and will be undertaken. Officials from CIRNAC responsibility centres with authority to provide funding through these two authorities will hold exploratory discussions with all concerned parties to determine the viability of streamlining and/or clarifying the policy intentions of capacity support to organizations, including IRO's. Agree. Better coordination of core and project funding would be advantageous to recipients and reduce administrative burden on both parties. Program review discussions to be led by departmental officials from PSD and Chief Finances, Results and Delivery Office (see response to Recommendation #5) with partner organizations, including IROs, as to the viability of a more flexible and comprehensive approach to organizational funding (core and project). |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy and Strategic Direction |

Start Date: |

| Completion Date: March 31, 2023 | |||

| 3. CIRNAC should work with Indigenous and federal partners to develop a strategy for the FICP Projects Stream that addresses the Supreme Court of Canada's 2016 Daniels decisions re: Section 91 (24) rights, and supports the self-determination and advancement of Indigenous governance institutions. | Agree. CIRNAC will work with its established Assessment of Current Policy Approaches to Métis and Non-Status Indians (MNSI) Committee and with key Métis and Non-Status Indian partners to streamline the FICP Projects stream to better address the Daniels decision. This will include necessary approval of revisions to the Terms and Conditions by Central Agencies. CIRNAC will work with Indigenous partners and established whole-of-government Post-Daniels Reconciliation Committees, including an intra-CIRNAC Assessment of Current Policy Approaches Committee, to assess gaps in approaches to working with MNSI communities. This work will contribute toward a new approach to a renewed relationship with MNSI groups. |

Director General of Indigenous and External Relations Branch |

Start Date: |

Completion Date: March 31, 2023 |

|||

| 4. CIRNAC should work with its Indigenous and federal partners to develop an engagement model that facilitates meaningful Indigenous input and participation in policy and program development as it relates to these authorities. The model should include a clear directive with guidance tools to ensure a coordinated and uniform approach by departmental officials to reduce engagement fatigue amongst Indigenous partners. | Agree. This is the third evaluation to make this recommendation for a C&PD/broader engagement approach and coordination. While the Indigenous and External Relations Branch is the departmental steward for C&PD, there is no official/unit responsible for all department engagements, model/approach, or directives. Consultation and Policy Development is one of many contribution authorities used across the Department to support engagement and dialogue with Indigenous peoples on policy and program-related matters. Creative and innovative ideas need to be developed with departmental stakeholders, based on recommendations received to date through engagement, evaluations, and independent reports. Consultation and Policy Development project managers across both CIRNAC and ISC can build on the input from partners by sharing best practices, lessons learned, and the results of funded projects. The result will be a compendium of possible changes to engagement that could be discussed and further refined with partners. Performing this function will require additional human resources within the policy unit of the Funding Arrangement and Management experts directorate to coordinate these efforts. As a result, the expected completion date for this action item must take into account the undertaking of the necessary steps to create these new positions, plan these efforts, and initiate the initial discussions with all concerned partners. |

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy and Strategic Direction working in collaboration with the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy and Strategic Direction at ISC |

Start Date: |

Completion Date: March 31, 2024 |

|||

| 5. CIRNAC should work with its Indigenous and federal partners to develop new performance measurement tools for core operational capacity support, departmental engagement efforts, and the new approach to the relationship with Section 91(24) Métis and Non-Status Indians groups that are meaningful and beneficial to both CIRNAC and recipients. | Agree. Performance monitoring and oversight of the BOC, FICP, and C&PD authorities must be improved. Recipient IRO's and federal stakeholders will be engaged to partner in the development of an improved performance measurement strategy that includes collection of relevant data (e.g., data on impact of core capacity funding on actual operations, as well as tangible policy/capacity/awareness outcomes as a result of engagements) to support results-based management. Policy and Strategic Direction will undertake a full program review of the funding relationship with organizations, including IROs, existing terms and conditions of the three contribution authorities evaluated, and related policies and processes to determine how best to coordinate and align the three programs (as well as considerations of relevant programs in other sectors, including Treaties and Aboriginal Government and ISC Regional Offices). This review will also inform how to better coordinate and align capacity support, engagement efforts, improve performance measurement tools, and the approach to the relationships with Section 91(24) Métis and Non-Status Indian groups. It is anticipated that this program review will result in the need for approval of significant revisions to the terms and conditions of the three contribution authorities by Central Agencies. |

Director General of Indigenous and External Relations Branch |

Start Date: |

Completion Date: March 31, 2023 |

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of Engagement and Capacity Support, which examined three funding authorities managed by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) with the support of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC). The three funding authorities covered by this evaluation are:

- Basic Organizational Capacity (BOC)

- Consultation and Policy Development (C&PD)

- Federal Interlocutor's Contribution Program (FICP)

The evaluation was conducted by CIRNAC's Evaluation Branch pursuant to the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Results, as well as Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act, which requires an evaluation of the relevance and effectiveness of all ongoing programs of grants and contributions to be produced every five years.

The purpose of the evaluation is to provide a neutral and evidence-based assessment of the performance and relevance of the authorities, and to inform decision-making and future directions.

1.2 Evaluation Scope and Methodology

Evaluation Scope

This evaluation examined the performance and relevance of the BOC, C&PD, and FICP funding authorities and considered activities carried out between April 1st, 2014 and March 31st, 2019. The evaluation covered the entire scope of the BOC funding authority, as well as the Governance and Project streams of FICP. Under C&PD, the evaluation primarily focused on the $10 million annual allocation, that is provided to Indigenous Representative Organization (IROs), except Métis recipients, as these organizations are also recipients of BOC, and FICP (as eligible).

In past evaluations, BOC, C&PD, and FICP funding authorities were evaluated separately. The purpose of combining the three authorities into one evaluation is to enable an overall assessment of the two key outcome areas that are shared by the three authorities, which are engagement with Indigenous partners and capacity support to IROs. As a practical result of covering three funding authorities, the evaluation's approach has been designed to provide a high-level perspective on CIRNAC's approach to Canada's relationship with and capacity support of IROs. While the evaluation does consider the experiences of non-IRO funding recipients (in particular with respect to C&PD), the main focus is on the approach to relationships with and impacts of funding provided to IROs.

Evaluation Methodology

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis of evidence collected through key informant interviews with representatives from funding recipient organizations as well as departmental stakeholders. Key informant interviews were semi-structured and held in-person within the National Capital Region, during site visits in Atlantic provinces and northern territories, or by phone. A total of 36 interviews were held with funding recipientsFootnote 1, including:

- twenty-six BOC recipients, comprised of four National Indigenous Organizations (NIOs) and 22 regional IROs;

- twenty-three C&PD recipients, including 17 IROs, four development organizations and two First Nations; and

- seven FICP recipients, including five IROs, one research institute and one non‑Indigenous organization.

Ten interviews were held with CIRNAC managers of the respective funding authorities and relationship holders with IROs, as well as with representatives from seven ISC regional offices. In September 2019, members of the evaluation team participated in an engagement session in the Atlantic region to gather perspectives from IROs and officials of ISC regarding BOC and C&PD. In summer 2019, evaluation team members traveled to Yukon and the Northwest Territories to conduct in-person interviews.

Qualitative data from interviews were transcribed, shared with participants for validation, and final transcripts were coded and analyzed. Key themes were identified by the evaluation team on the basis of the coded data through a group exercise.

Findings and conclusions for this evaluation are also supplemented by a literature review, review of key program documents and program financial data.

Limitations

A limitation of the evaluation is that two of the five NIOs chose not to be interviewed for the evaluation. However, both NIOs not interviewed have representative bodies at the regional level that did participate in this evaluation.

A second limitation of the evaluation is the targeted focus on engagement and capacity support for IROs. As the majority of recipients of the C&PD authority are not IROs, the evaluation is unable to speak to the relevance and effectiveness of this authority outside of its applicability to the Department's support of IROs and the experiences thereof. However, engagement with IROs supported through C&PD is within the scope of this evaluation.

2. Program Background and Description

IROs are present at the national, territorial, and regional level and represent or advocate on behalf of memberships of First Nations, Inuit, Métis and Non-Status Indian communities and organizations. The Government of Canada has provided funding for Indigenous advocacy organizations since the 1960's. Today these organizations are considered to be important intergovernmental partners to both federal and provincial governments.Footnote 2 BOC funding is one of the ways the Government supports these organizations in their work, providing a minimum level of capacity to advise the Government of Canada of their members' needs and interests when developing policies and programs. To support the work of IROs across Canada, CIRNAC provides both basic funding, through the BOC authority, as well as project funding, through the C&PD or FICP funding authorities, based on specified eligibility criteria.

2.1 Basic Organizational Capacity

According to the 2010 departmental policy, BOC is intended to support IROs in their political advocacy, membership liaison, policy development, and project implementation activities. BOC contributes to these activities by providing funding to cover some core capacity costs, including the salaries of one or two executives, rent, utilities, an annual general assembly of members and associated travel costs. Eligible organizations are those thatFootnote 3:

- are a recognized IRO at the national, territorial, or regional level; or an autonomous, national Indigenous women's organization representing the interests of its respective First Nations, Inuit, Métis and Non-Status Indian constituents;

- are incorporated under Part II of the Canada Corporations Act;

- have memberships restricted to a defined or identifiable group of Indigenous communities and/or organizations;

- have a mandate from members to represent or advocate on behalf of those members; and

- are not in receipt of any other core funding from the federal government for the purposes of maintaining basic organizational capacity to represent or advocate for the interest of their membersFootnote 4.

During the period of the evaluation, there were 50 IROs receiving BOC funding, of which five are NIOs and 44 are regional IROs. The 50 IROs include 24 First Nations organizations, nine Métis organizations, eight Inuit organizations, seven Non-Status Indian organizations, and two women's organizations.

The BOC authority falls under the core departmental responsibility of Rights and Self‑Determination, and contributes to the following departmental results:

- Indigenous peoples and Northerners determine their political, economic, social and cultural development; and

- Indigenous peoples and Northerners advance their governance institutions.

BOC funding is provided to build core organizational capacity to help IROs to contribute to and participate in government policy and program development (immediate outcome); and to achieve better informed IROs, their members, and elected officials (intermediate outcome); that is in turn expected to contribute to Indigenous peoples and Northerners advancing their governance institutions (ultimate outcome).Footnote 5

BOC funding is managed by the Policy and Strategic Direction Sector (specifically the Funding Arrangement Management Experts Directorate), which also distributes funds directly to NIOs, as well as to Métis and Non-Status Indian IROs. Funding for all other regional IROs flows to ISC regional offices for distribution to recipients. BOC expenditures during the evaluation period are presented in Table 1.

| Year | National* IROs (Six Organizations) | Regional IROs (44 Organizations) |

Total Actuals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013/14 | $9,623,276 | $18,820,083 | $28,443,359 |

| 2014/15 | $8,640,398 | $12,468,402 | $21,108,800 |

| 2015/16 | $8,607,775 | $12,556,886 | $21,164,661 |

| 2016/17 | $10,634,946 | $15,811,893 | $26,446,839 |

| 2017/18 | $11,642,447 | $18,768,554 | $30,411,001 |

| 2018/19 | $11,642,447 | $20,066,751 | $31,709,198 |

| Total | $60,791,289 | $98,492,569 | $159,283,858 |

*National IROs includes: Assembly of First Nations, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, Women of the Métis Nation, Native Women's Association of Canada, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. |

|||

2.2 Consultation and Policy Development

This authority funds activities that investigate, develop, propose, review, inform or consult on policy matters within the mandate of the Department, and include activities such as workshops, studies, meetings and policy development. The funding supports the Department to engage with Status Indians and Inuit on key policy issues. Eligible recipients include Indian, Inuit and Innu peoples (e.g. Tribal Councils; Indian Education Authorities). As the C&PD authority exists to support engagements not otherwise covered by a specific program authority, it is not specific to any single issue or program and it may be used by any program/region in the Department. Consultations triggered by the Crown's legal duty to consult are not part of the C&PD authority.

C&PD project funding is allocated on a case-by-case basis and is subject to funding availability. Project funding is accessed through proposals for specific projects or initiatives with fixed timeframes.

There are two dimensions to the C&PD funding authority. Budget 2016 allocated $10 million annually over five years to provide project funding specifically to BOC recipients. C&PD is also a departmental financial code used to flow program funds for engagements. C&PD expenditures are managed by the Funding Arrangement Management Experts Directorate of Policy and Strategic Direction, which has the ultimate authority to sign off on funding under this financial code (both the $10 million envelope for IRO project funding and program engagement funding).

| Year | Total Actuals |

|---|---|

| 2013/14 | $ 23,531,425 |

| 2014/15 | $ 15,468,246 |

| 2015/16 | $ 16,074,751 |

| 2016/17 | $ 24,029,251 |

| 2017/18 | $ 62,540,219 |

| 2018/19 | $ 46,146,528 |

| Total | $ 187,790,420 |

2.3 Federal Interlocutors Contribution Program

The FICP aims to enhance the capacity, stability, and accountability of both Métis and Non‑Status and other off-reserve IROs to represent their members, and enable these groups to build partnerships with federal and provincial governments and the private sector. It works specifically to:

- support the Métis National Council (MNC) and its governing members in their transition to self‑government and self-determination by enhancing their governance capacity;

- develop and standardize "objectively verifiable membership systems" for Section 35 rights‑holding Métis collectives in accordance with the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Powley (2003); and

- provide capacity and support for engagement on the development of key policy positions by Métis, Non-Status Indigenous organizations.

The FICP Projects Stream funds annual and multi-year projects for eligible recipients. The stream has funded numerous projects consistent with the objectives pursued by the Office of the Federal Interlocutor at the national, provincial, regional or urban level for the benefit of Métis, Non-Status Indian people or off-reserve Indigenous people. Some examples include:

- the development and distribution of Métis-specific classroom materials for K-12;

- funding to universities working on Métis Nation specific research; and

- governance and capacity related initiatives for eligible organizations.

For organizations to qualify for FICP, they must be a non-profit Métis, Non-Status Indian, or other off-reserve Indigenous organization or institution; or other non-Indigenous organization or institution, including professional research organizations.

In addition to providing project funding, the FICP funding authority includes a second stream of funding, devoted to Métis Governance (formerly Powley), which is available to the MNC and its governing members as ongoing flexible governance and capacity funding.

The primary external partners involved in the FICP include the MNC and its governing members, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and its affiliates as well as IROs that represent Métis outside of the MNC and Non-Status Indian representative organizations. All Indigenous peoples in Canada represented by one or more of the aforementioned organizations/governing bodies are notable stakeholders.

The FICP Governance Stream is managed by the Reconciliation Secretariat, while the FICP Projects Stream is managed by the Indigenous Relations and Policy Directorate – formerly the Métis and Non-Status Indian Relations Directorate. Both units fall under the authority of the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy and Strategic Direction within CIRNAC.

| Year | Total Actuals |

|---|---|

| 2013/14 | $ 10,917,591 |

| 2014/15 | $ 7,441,474 |

| 2015/16 | $ 14,901,192 |

| 2016/17 | $ 21,614,187 |

| 2017/18 | $ 29,416,595 |

| 2018/19 | $ 81,523,946 |

| Total | $ 165,814,985 |

For Performance Measurement information for all three authorities, see Annex A.

2.4 Previous Evaluations

The 2014 Evaluation of Engagement and Policy Development

The evaluation recommended that the Department:

- review and revise, as appropriate, the BOC and C&PD's expected results in order to provide greater clarity and distinction between the two authorities; and

- track the engagements supported by the C&PD authority. The tracking tool should include the type of activity, the purpose, the location, and participants involved in the engagement activity.

The 2014 Evaluation of the Federal Interlocutor's Contribution Program and Powley Initiative

The evaluation recommended that the Department:

- work with Métis and Non-Status Indian organizations and federal and provincial partners to establish a clear set of objectives for the FICP moving forward that clearly delineates roles and responsibilities and expectations of stakeholders.

3. Evaluation Findings

This section presents findings as they relate to Performance: Impacts on Outcomes; Performance: Efficiencies; and Relevance: Alignment of Current Approach with Self‑Determination and a Renewed Relationship. Since the findings build on each other, the recommendations are provided together in the Conclusion and Recommendations section.

Relevant Departmental Intended Outcomes for BOC, C&PD, and FICP

- Indigenous peoples and Northerners determine their political, economic and social development (CIRNAC Departmental Results articulated in the 2018-19 Departmental Plan);

- Indigenous peoples and Northerners advance their governance institutions (C&PD and FICP Performance Information Profiles, April 2018); and

- Support the rebuilding of Indigenous nations and governments and advance Indigenous self-determination and inherent right of self-government (Recognition of Rights Framework).

3.1 Performance: Impacts on Outcomes

Basic Organizational Capacity

Impacts on Outcomes

Finding 1. BOC funding is not fully attaining the intended outcome of IRO contributions to and in participation with government policy and program development in a meaningful and equitable manner.

Finding 2. The Performance Information Profile for the BOC authority does not include relevant indicators for tracking the impact of program expenditures on expected outcomes.

The theory of change for the BOC authority is that contributions made to recipients will establish core organizational capacity to make IROs capable of contributing to and participating in government policy and program development (immediate outcome). This core organizational capacity is expected to contribute to better informed representative Indigenous organizations, their members, and elected officials (intermediate outcome), that is in turn expected to contribute to Indigenous peoples and Northerners advancing their governance institutions (ultimate outcome). Performance metrics for the BOC authority are:

- the percentage of BOC funding committed to IROs; and

- the percentage of IROs scoring "very low" risk in terms of financial management and governance capacity (as measured by the Department's General Assessment process).

At the immediate outcome level, there are no performance indicators in place to track changes in the level of core capacity of IROs or changes in the ability of IROs to contribute to and participate in government policy and program development. The evaluation team sought to understand the perspectives of IROs regarding changes to their core capacity and in their ability to contribute to and participate in government policy and program development during the period of the evaluation.

BOC's Contribution to IROs

According to recipient IROs, BOC is an important and appreciated source of funds supporting some of their core operating costs. However, the extent to which interviewees indicated that BOC positions their organizations to effectively and meaningfully advocate on behalf of their membership was highly variable. BOC funding provides organizations with some core organizational support to be able to advocate on behalf of their members with various levels of government. Virtually every IRO that spoke with evaluators voiced their need and gratitude for the dependability of BOC funding. However, IROs also noted – with equal unanimity – that basic costs such as rent, utilities, one or two executive salaries, and an annual gathering of membership were not the full extent of their actual core capacity costs. Recipient IRO participants in this evaluation said that a fair list of the core expenses required to perform their day-to-day business would include:

- a functioning workspace;

- a full contingent of staff (recruited and retained through stable and competitive compensation and benefits packages);

- a travel budget reflective of geographic location and regular involvement in engagement on federal (not just CIRNAC) policy and programs; and

- a small set aside of contingency funds for unanticipated emergencies.

The vast majority of IROs participating in this evaluation indicated that the level of BOC funding over the period of evaluation was significantly less than required to staff and operate their robust organizations. Therefore, in and of itself, BOC does not position organizations to contribute to and participate in policy and program development. Rather, BOC funding provides support for covering some basic operating costs and the Government may then make available additional dollars based on its identified priorities.

Prior to drastic budget cuts as a result of the Deficit Reduction Action Plan in 2012, organizations were funded according to a funding formula that considered factors such as region and population represented by the organization. Since 2012, funding levels have not been restored to those prior to 2012; this has resulted in IROs having to seek alternative sources of funding for their needs.

Organizational existence and financial stability, while necessary for an IRO to function on the most basic level, do not necessarily enable the level of capacity required to provide meaningful contributions and input into federal endeavours – and to support the departmental goals of advancing Indigenous self-determination and a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples. Meaningful engagement involves stakeholders having an opportunity to influence outcomes before they are decided, and provides an opportunity to influence future decisions/policy.Footnote 6 Under the current approach, IROs are working tirelessly to contribute and participate in government policy and program development, when provided with additional support to do so. If core capacity funding to IROs was more reflective of real core capacity costs, these contributions would likely increase in both scale and depth.

At the intermediate and ultimate outcome levels, there are no performance indicators in place to track changes in the degree to which representative Indigenous organizations, their members, and elected officials are increasingly informed as a result of BOC, or BOC's contribution to Indigenous peoples. As described above, the evaluation team found little evidence that BOC funding on its own has contributed to these outcomes beyond supporting minimal basic operating costs.

Clarity For Funding Levels

No funding formula currently exists for the BOC authority to guide the equitable basis of funding between IROs. The most recent policy document, written in 2010, is no longer in effect as a result of government-wide budget cuts in 2012. These cuts impacted BOC's funding levels significantly, as amounts provided to each recipient IRO post-2012 were based on pre‑determined levels. The pre-2012 funding formula took into account the number of regional offices, the number of IROs in each region, and the populations of each IRO's membership (based on on-reserve First Nations census data), and divided the total amount available based on these considerations. The cuts in 2012 removed the use of a funding formula and allocations have not returned to pre-2012 levels for the majority of recipients.

Many recipients stated that it is unclear to them how their BOC funding levels are calculated; many do not understand why they receive the amounts that they do, and there was sentiment expressed that the principal recipients of funding are NIOs, which risks constraining access to funds for smaller and/or regional IROs.

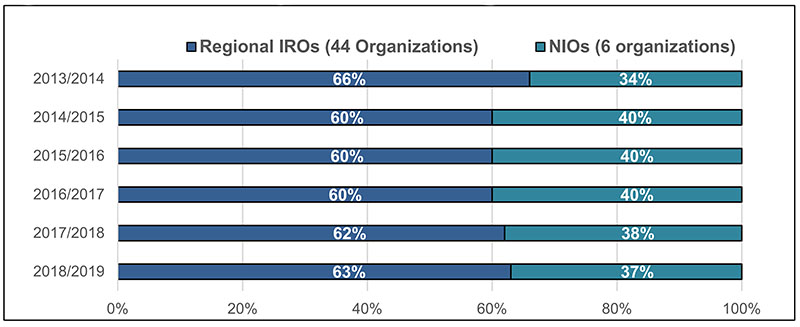

Figure 1: Distribution of funding between NIOs and Regional IROs

Text alternative for Figure 1: Distribution of funding between NIOs and Regional IROs

Figure 1 is a stacked bar chart showing funding percentage distributions over a six year period spanning from 2013 to 2019. Funding recipients included 44 IROs and 6 NIOs.

In 2013-2014, Regional IROs received 66% and NIOs received 34% of the total funding.

In 2014-2015, Regional IROs received 60% and NIOs received 40% of the total funding.

In 2015-2016, Regional IROs received 60% and NIOs received 40% of the total funding.

In 2016-2017, Regional IROs received 60% and NIOs received 40% of the total funding.

In 2017-2018, Regional IROs received 62% and NIOs received 38% of the total funding.

In 2018-2019, Regional IROs received 63% and NIOs received 37% of the total funding.

Recipients in northern and rural areas have indicated that the funding they receive does not seem to take into consideration the costs associated with doing business in these areas. For example, the travel costs for an organization in the North to participate in engagements held in the South, are higher based on the price of flights and the amount of time required to travel. Other organizations have expressed that they do not feel that BOC funding provides adequate support to reflect the number of members the organizations serves.

This evaluation found a difference in approach to relationship-building and the level of core capacity funding between national and regional IROs. Between 2014/15 and 2018/19, each year, between 35 percent and 39 percent of the total BOC envelope intended for 50 recipients was allocated to five NIOs. For at least two (the Assembly of First Nations and the MNC, as well as Inuit Tapariit Kanatami to a lesser extent) of the five NIOs, BOC funding was said to not only better support core capacity needs, but was also achieved through negotiation between the NIOs and the Department. These negotiated agreements at the national level often also take into consideration program and project-specific funding agreements under the umbrella of a broader comprehensive funding agreement, seemingly in recognition of the benefits for both parties in having the total amount of funded activities (and funds to carry out these activities) be stable and predictable. The three IROs representing Indigenous women do not have funding agreements of this nature; however, new partnership agreements were signed with the Native Women's Association of Canada (2019) and Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada (2017) during the evaluation period. Neither of these agreements included guaranteed capacity or project funding.

The Reality of IROs: Who they are and What they do

Finding 3. BOC funding does not take into account the broader mandates of IROs, which enhance their ability to meaningfully contribute to and participate in government policy and program development.

BOC recipient IROs across Canada often listed offerings of wide-ranging programs (from job training initiatives to elder support to childrearing training classes for recent or expecting mothers, among many others), housing developments (most often subsidized rental units), and other business ventures (from natural resource harvesting to leasing of commercial spaces) as activities performed by their organizations in addition to political advocacy. As non-profit corporations, each revenue-generating activity is used to provide such programs and the staff required to do so on a temporary basis as additional funding streams that are project‑based are by nature less stable, predictable, and sufficient to meet existing need. IROs also frequently represent their member nations in self-government negotiations and treaty claims/litigation with the federal government.

As currently designed, BOC is not intended to support IROs in delivering on the full extent of their mandates – it is a support for input on CIRNAC policy and programs. The actual operating capacity of IROs to fulfill the mandates for which they were established by their members is primarily funded through additional authorities and programs (most often from CIRNAC, as well as other government departments) on a proposal and project‑specific basis. However, these additional aspects of their mandate beyond advocacy were routinely identified by recipient IRO participants in this evaluation as providing organizations with a more holistic understanding of the needs of their members, which was seen as essential to provide meaningful and effective advocacy.

BOC funding is therefore focused on the subsistence of IROs, as opposed to funding the full extent of their mandates. Without the ability to fulfill its mandate, an organization may not be able to fully contribute to government policy and program development.

When examining the full suite of funding used by IROs and the relative contribution of the predictable funding (BOC), there is a disconnect between the objective of BOC as supporting an organization's basic capacity and its primary outcome – Indigenous contributions to policy development – particularly when a wider view of the role of IROs is taken into consideration as a valuable element of desired inputs. According to many interviewees, BOC's intended outcomes would be much more effectively supported if BOC was considered more of a support for actual 'core' (i.e. costs IROs consider to be necessary to fulfill their mandates) as opposed to 'basic' (i.e. the costs associated with simply existing as an IRO) operational capacity, and with an acknowledgement of the full mandates of recipient IROs.

Consultation and Policy Development

Impacts on Outcomes

Finding 4. Engagement of IROs increased during the period of evaluation for the development of government policy and programs; however, IROs routinely expressed that engagements were not always conducted meaningfully or resourced adequately.

Finding 5. The Performance Information Profile for the C&PD authority does not include relevant indicators for tracking the impact of program expenditures on expected outcomes.

The theory of change for the C&PD authority is that contributions made to recipients will allow for their participation in engagements, which will lead to improved awareness by Indigenous and government stakeholders of each others' positions on policies and programs (immediate outcome). Engagement with stakeholders is expected to influence the development of policies and programs (intermediate outcome), and the ultimate outcome for the authority is: consideration of Indigenous engagement in CIRNAC policies and programs. The sole performance metric for the C&PD authority is:

- number of engagements held with stakeholders, which sought to influence the development of CIRNAC's policies and programs.

At the immediate outcome level, there are no performance indicators in place to track changes in the level of awareness of priorities on the part of IROs and departmental staff. The evaluation team did not measure changes in levels of awareness as it relates to specific engagement topics, which could be better done in the context of and immediately following an engagement session or process. Rather, the evaluation team gathered the perspectives of IROs regarding the extent to which they were involved in engagements over the period of the evaluation as well as the quality of those engagements. The information gathered by the evaluation is considered to relate closely to the intended immediate outcome, as it is expected that quality engagement would result in improved awareness by all parties of each other's respective positions.

Engagement is Increasing in Quantity, but not Necessarily in Quality

Many recipients of C&PD funding noted an increase in departmental requests for engagement on a wide spectrum of federal policy and program reform over the period of evaluation. The evaluation team considers that this increase is largely attributed to the Government's commitment to a renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government, and Inuit-Crown relationship with Indigenous peoples — one based on recognition of rights, respect, and partnership. Seen by most Indigenous organizations interviewed as a positive development, the increase in engagement activities was not seen to include the provision of sufficient resources (time as well as money) to contribute and participate meaningfully in engagements.

For those IROs engaged on a policy or program during the evaluation period, the evaluation found a general sentiment that organizations are more involved in reform discussions, but it's not clear the extent to which they're being heard due to:

- limited time allotted for discussion and consideration of the policy or program area by IROs and their members;

- a sense that decisions were already made within government;

- perception that there is a heavy reliance on NIOs, particularly the Assembly of First Nations, and not necessarily on IROs and First Nations; and

- a lack of mechanism by which to determine how their perspectives were incorporated into policy.

If not approached in a way that provides both adequate time and resources, engagement efforts can be detrimental to relationships with external partners. Increased engagement intersects with increasing research fatigue on the part of the under-resourced. This approach to engagement leads to further stretching these organizations' time, human and financial resources.

At the intermediate outcome level, there are no performance indicators in place to track changes in the degree and/or way in which engagement with stakeholders influences the development of policies and programs. The evaluation team sought to understand contributions to this outcome through interviews with IROs and departmental staff. IROs expressed that they had no clear sense of the way in which their feedback had been taken into consideration in policies and programs. The Department's unit responsible for managing C&PD were not aware of existing and uniform feedback mechanisms in place across the Department or its various sectors.

Finally, the evaluation team considers that the ultimate outcome for this authority does not follow logically from the earlier outcome statements, in that the authority is intended to influence policy and programs (intermediate outcome) – presumably with a view to improving their quality and sensitivity to the needs of Indigenous stakeholders – which does not then follow to a consideration of Indigenous inputs at the ultimate outcome level.

C&PD's Connection to BOC, FICP & IROs

Finding 6. There is overlap and a lack of clarity between the three authorities: BOC, C&PD, and FICP. The C&PD authority is regularly viewed and used by departmental officials and recipient IROs as a 'top up’ to core capacity (BOC) funding.

The additional $10 million of dedicated C&PD funds for IROs that is managed by Funding Arrangement Management Experts is mainly (70 percent) funded by CIRNAC to IROs via the regional offices of ISC for distribution to IROs. A smaller percentage is distributed to NIOs directly by Funding Arrangement Management Experts, with an even smaller percentage kept in reserve for unforeseen contingencies. While C&PD funds are meant to support the collection of Indigenous input on policy and program development, the evaluation finds that this dedicated $10 million is in practice additional capacity support for recognized IROs and therefore supplementing BOC funding.

Many recipient IROs and departmental officials that participated in this evaluation referred to C&PD expenditures as ‘topping up' insufficient BOC funding, particularly in a post-Deficit Reduction Action Plan context. The interconnectedness of the BOC and C&PD authorities is further demonstrated when their outputs are viewed together as being necessary to achieve their shared intended outcomes – or in other words, BOC and C&PD combined, provide recipients with the core operational capacity to contribute and participate in government policy and program development, when provided with sufficient engagement funding.

Previous evaluations of C&PD and BOC noted that there was an overlap and lack of clarity between the BOC and C&PD authorities. The C&PD authority is intended to be a vehicle for a wide range of engagements between CIRNAC and Indigenous peoples for the development and implementation of departmental policy and programming. According to the C&PD Terms and Conditions, eligible activities are "those that investigate, develop, propose, review inform or consult on policy matters within the mandate of Department of Indian and Northern Development (DIAND)". The specific types of eligible activities are workshops, studies, meetings, and policy development, all for subject matter related to CIRNAC policy and programming. Through the interview process and reviews of literature and documentation, the current evaluation, as well as the two previous evaluations found that such flexibility is desirable given that C&PD funding is used across the range of CIRNAC activities and Indigenous organizations in Canada. If engagement processes and objectives are to reflect collaboration and partnership, then the Department should be positioned to respond to emerging issues and priorities that impact its mandate.

This flexibility, an obvious strength of the C&PD authority, can also be seen as a weakness. While it is clear that flexibility is required, the C&PD authority can be interpreted very loosely because of a lack of clarity around what can be funded or, perhaps more importantly, what cannot be funded. Such loose interpretations means that the C&PD authority often gets used to flow monies that may be justified, but fit better under the BOC authority because the funded activities are not always directly related to engagement initiatives. When monies are allocated in this way, the expected results that derive from consultations and the associated reporting will not occur.

It should be noted that C&PD funding is intended to support specific engagement initiatives linked with defined deliverables and outcomes that are related to policy and program development and implementation. As noted above, supporting an ongoing function using the C&PD authority suggests a mismatch and that the C&PD funding is sometimes used as "top-up" money to complement existing BOC resources. Such cases could indicate issues around the level and use of funding as well as a lack of clarity concerning which authority should be used.

The intended purpose of the C&PD authority can be understood in the context of two important types of funding provided to CIRNAC recipients: core funding; and, project funding. Core funding is designed to support the basic existence of a recipient organization and includes categories such as staff salaries and costs for basic maintenance and utilities. Project funding extends beyond these categories to include specific initiatives that, conceptually, have beginnings and ends. Projects (i.e., engagement activities) may be multi-year, but they are not ongoing because they have a foreseeable end with clearly defined expected results. It is apparent in program documentation, that the intent of the C&PD is for clearly defined engagement initiatives. However, as noted in this evaluation, C&PD is often used to ‘top-up' core operations.

The confusion between core funding and project funding can be seen in the idea of "core-like" activities. Core-like activities are those that do not seem to fit neatly under either the core or project categories: they usually seem closely related to the raison d'être of the organization, and extend beyond basics such as buildings, utilities and salaries. A comparison of the BOC authority and the C&PD authority reveals a potential source of confusion. The BOC authority, is intended to be for core operations, while the C&PD authority is to be dedicated to project funding for consultations on policy and program development and implementation, however, their stated objectives are very similar. In addition, the FICP authority also shares similar objectives to BOC and C&PD. Table 4 shows a comparison of the main expected results of the three authorities.

| BOC | C&PD | FICP |

|---|---|---|

Core organizational capacity to make Indigenous Representative Organizations capable of contributing and participating in government policy and program development |

Engagement with stakeholders influences the development of CIRNAC and ISC policies and programs |

Increased organizational and governance capacity in Métis organizations Crown-Métis Nation Government-to-Government relationship is strengthened Provide capacity and support for engagement on the development of key policy positions by Métis, Non-Status Indigenous organizations. |

From this comparison it can be seen that the three authorities have similar objectives. BOC and C&PD authorities both pertain to participating in program and policy development. The FICP authority also has commonalities with BOC and C&PD. FICP's Governance Stream shares similar objectives with BOC, while FICP's Project Stream is similar to C&PD. There are also commonalities between the authorities in terms of recipients. BOC and C&PD provide funding to IROs and Indigenous peoples, and the FICP and BOC support Métis and Non-Status Indian Representative Organizations.

The two previous evaluations made recommendations that were intended to resolve the overlap issues between the BOC and C&PD authorities. The 2009 Evaluation of Consultation and Policy Development and Basic Organizational Capacity Funding recommended that the BOC and C&PD authorities should be combined because of their similarity. The 2014 Evaluation of Engagement and Policy Development, which only covered the C&PD authority, but made reference to the BOC authority because it's similarity with C&PD, recommended that their differences be clarified to ensure that C&PD funding is allocated for engagement activities to inform policy and program development, rather than for core and core-like activities.

The current evaluation is broader than the two previous evaluations because it also includes the FICP authority, however, it makes similar observations around the overlap of the authorities. Because there are now three authorities that have similar objectives and recipients, this evaluation finds that work should be undertaken to improve coordination and alignment between the authorities.

There are a variety of ways to improve coordination and alignment between authorities, such as putting in place multiple funding streams (e.g., core funding, project funding, and capacity building funding) to Regional Operations from the authorities. Regardless of the specific approach that is taken, the authorities should enable the strategic coordination of funding and should reduce the overlap to improve efficiencies in program delivery and reporting on the funding.

Federal Interlocutors Contribution Program

Impact on Outcomes

Finding 7. There is evidence that the FICP Governance Stream is contributing to intended outcomes, including the development and maintenance of an objectively verifiable membership system for Métis in Canada.

Finding 8. The intended outcomes theory of change for the FICP Projects Stream is unclear and funded projects do not necessarily correspond with intended outcomes or strategic direction.

Finding 9. There is a lack of clarity on how to proceed with Métis and Non-Status Indian partners following the Supreme Court of Canada’s Daniels decision.

Finding 10. There is a lack of negotiated, multi‑year funding agreements with national organizations representing women and Non‑Status Indians.

The theory of change for the FICP authority is that contributions made to recipients will allow for the establishment and maintenance of objectively verifiable registries of Section 35 Métis rights‑holders (immediate outcome), which will contribute to increasing organizational and governance capacity in Métis organizations (intermediate outcome), which will in turn contribute to strengthening the Crown-Métis Nation Government-to-Government relationship (ultimate outcome). This theory of change seems to apply only to the FICP Governance Stream of the FICP funding authority which targets Section 35 Métis rights-holders (MNC and Governing Members), and not to the FICP Project Stream, which is available to any non-profit Métis, Non-Status Indian, other off-reserve Indigenous organizations or institutions; or other non-Indigenous organizations or institutions. The intended outcome for the FICP Projects Stream is less clear.

There are many performance indicators for the FICP authority, including:

- percentage of Governing Members participating in CIRNAC's exploratory tables;

- shared CIRNAC-led priorities identified in the Canada-Métis Nation Accord are advanced through the Permanent Bilateral Mechanism;

- number of Métis organizations that have transitioned from non-profit organizations to representative Métis governments;

- percentage of Métis and non-status Indian organizations scoring "very low" risk in terms of financial management and governance capacity;

- percentage of Governing Members that have implemented Canada Standards Association Registry Standards; and

- number of registries with confirmed and certain membership lists.

It is not clear whether these indicators are systematically tracked and used to inform program planning, accountability and learning.

FICP Governance - A Strong Support for Métis Governments

In the Governance Stream of FICP funding, the evaluation found a robust, intentional, and effective vehicle for Canada's support to the MNC Governing Members on their respective paths to self-government. In particular, the evaluation found an intentional approach on the part of the FICP Governance Stream to anticipate and systematically support MNC Governing Members in addressing each element of the traditional negotiation process toward self-government, as typically conducted by the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector of CIRNAC. This approach demonstrated the clear benefits and increased efficiencies for all parties in providing such intentional support to Indigenous partners in achieving the goals and end-destinations determined by Indigenous peoples themselves, and thus is directly aligned with departmental objectives.

For example, as it relates to the immediate outcome of establishing and maintaining registries, MNC Governing Members interviewed through this evaluation spoke to continued progress in the development and maintenance of their registries as a result of dedicated FICP funding. While funding for Métis registries has been ongoing since the Supreme Court of Canada's Powley decision in 2004, there has been an increase in requests for Métis citizenship subsequent to the Supreme Court of Canada's Daniels Decision in 2016. There has also been an increased recognition of Métis governments by the Crown and associated funding for Métis governments to offer services to their citizens in the period of the evaluation. Aside from managing this increased demand on the registration process, the following additional activities have been undertaken by some MNC Governing Members to develop and strengthen registries: improvement of the security of files and recordkeeping; transfer of a registry from a paper based registry to an automated database; initiation of a joint process between MNC Governing Members, the Reconciliation Secretariat and the Canada Standards Association to establish a standard on operations of Powley-compliant Métis registries jointly between MNC Governing Members, the Reconciliation Secretariat and the Canada Standards Association.

Funding recipients also noted the foundational nature of this aspect of FICP funding to all other operations of their governments on behalf of their citizens.

As it relates to the intermediate outcome of increasing organizational and governance capacity, MNC Governing Members worked on various areas according to their priorities as per the design of the FICP Governance Funding Stream. For example, one MNC Governing Member mentioned their focus on registering citizens and building a governance structure, or "the infrastructure of what the government will be and how we deliver programs and services", including a strategic plan, as well as moving forward on self-government negotiations.

As it relates to the ultimate outcome of strengthening the Crown-Métis relationships, Métis Government Recognition and Self-Government Agreements were signed in June 2019 with the Métis Nation of Alberta, the Métis Nation of Ontario, and the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan. Respondents in the evaluation consider that support provided by the FICP authority to members of the Métis Nation, with the intention of achieving self-government, contributed to this historic achievement; in particular, by allowing for the establishment of objectively verifiable membership registries by MNC Governing Members. This follows on the equally historic announcement in 2017 that, as part of the National Housing Strategy, $500 million will be provided over 10 years to support a Métis Nation housing strategy. The evaluation found that Métis governments consider these significant achievements as indicators of the advancement of Canada's relationship with the Métis Nation and ongoing efforts at reconciliation.

FICP Governance funding is negotiated, multi-year, substantial, and flexible, and therefore allows the MNC and Governing Members to determine their own priorities and manage funds as they best see fit (including the means to reallocate and rollover funding), with minimal reporting requirements. Thus, the Governance Stream's design and implementation demonstrated a positive example of how a government-to-government relationship operates in practice based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation and partnership and how the design of the funding model contributes to the achievement of outcomes.

FICP Projects

As mentioned above, there is no clear theory of change for the FICP Projects Stream. The intended outcomes for the FICP authority refer only to Métis Nation organizations, not non-MNC-affiliated organizations or Non-Status Indian groups, both of which are eligible for FICP funding. In addition, the projects funded under this authority are not strongly connected to an intended outcome, and ultimately program staff indicated a lack of clarity as to what projects ought to be funded and why. As such, the evaluation found that the FICP Projects Stream is in need of further consideration and strategic planning to be more intentional in its approach, and therefore increase its effectiveness.

The Supreme Court of Canada's 2016 decision in Daniels v Canada in recognition of the "Indian" status of Métis and Non-Status Indians, as defined in Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, and resulting federal fiduciary responsibility towards Métis and Non-Status Indians, sparked a significant increase in demand for FICP project funding. However, no strategy or policy direction has yet been developed by CIRNAC in response to this landmark ruling. As a result, interested potential applicants are told to apply, however, the existing $3.7 million is already oversubscribed. The evaluation found that there is not a clear strategy and policy approach for the authority.

Gender Equity

The recently established Reconciliation Secretariat within CIRNAC's Policy and Strategic Direction Sector has undergone considerable restructuring over the period of evaluation, and now includes (but is not limited to) three separate directorates for Crown-First Nations, Crown-Métis, and Crown-Inuit relations. With responsibility for the Permanent Bilateral Mechanisms, of which the Assembly of First Nations, MNC and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami are participants, the inclusion of responsibility for relationships with these national Indigenous partner organizations makes sense within the Secretariat. The responsibility for relationships with Métis and Non-Status Indians and women's IROs are not a part of the Secretariat. These two distinctions-based categories are managed by the Indigenous Relations and Policy Directorate under the Director General of Aboriginal and External Relations, the branch which manages the three authorities examined through this evaluation.

Accords were signed in 2018-2019 with the Native Women's Association of Canada and the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. The accord with the Native's Women's Association of Canada came with related (albeit not guaranteed as part of the accord) funding, while the accord with Congress of Aboriginal People did not include funding or a strategy to address the bourgeoning community of Section 91(24) claimants/applicants.

3.2 Performance: Efficiencies

Finding 11. It is not an efficient use of the Department’s and IROs’ resources and time to require the application, approval, and preparation of several separate funding agreements, and delivery thereof, with the same recipients in a given year.

The majority of recipient IRO participants in this evaluation devote considerable resources to extensive proposal writing towards the end of each fiscal year. However, these efforts are made not only to ensure the receipt of project funding to run programs, but also to keep the organization functioning through the levying of administrative fees on each contribution agreement. These administrative fees, sometimes aggregated across dozens of contribution agreements, often cover the salaries of contractors and permanent staff within an IRO through complicated and time-consuming financial calculations. Relying on project funding for many successive years yields significant challenges in budgeting and financial management, leaving the organization at risk of unexpected deficits.Footnote 7 Moran et al (2016) notes that fiscal and administrative fragmentation (e.g. short-term loans with very specific instructions and a lot of reporting) can be overwhelming and inefficient for Indigenous organizations.Footnote 8

A more efficient model would integrate all costs associated with developing the necessary core capacity of an IRO into one single funding agreement and thereby reduce the number of individual funding agreements between organizations and the Department. This would result in fewer requests for proposals, financial transfers and reports. The evaluation heard of a directive within the Policy and Strategic Direction Sector to begin talks on Comprehensive Funding AgreementsFootnote 9 with all BOC recipients as of April 1, 2020. The evaluation supports this direction with the recommendation that discussions include the full mandate of recipient IROs, determined through engagement with IROs, and that implementation be phased in over a reasonable period of time.

Finding 12. Delays in the delivery of committed funds to IROs are detrimental to the effective and efficient use of funds by organizations, and undermine positive achievements made by Canada to renew the relationship with Indigenous peoples.

BOC funding was provided in a timely and predictable manner to recipients for the majority of the evaluation period, with the exception of the final year under review due to complications in processing transactions related to the introduction of a new departmental financial software.

According to the previous evaluation of the C&PD authority, the authority experienced significant challenges in delivering funding in a timely manner and these challenges have continued. Most recently, the transformation of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada into CIRNAC and ISC contributed to delays in transferring payments. In addition, payments are sometimes delayed because organisations do not always submit the proper documentation in a timely manner. Delays in obtaining project funding have led to delays in staffing and project implementation, particularly for smaller organizations that are not in a position to cash manage. Some recipients shared that delays in funding were accompanied with uncertainty as to whether initial budgets and proposed activities were still expected within the initially proposed time frame; others had better clarity regarding any required changes in time frame or budget, but needed to dedicate additional staff time to re-work initial proposals to fit within new budgets and timelines.

FICP Governance recipients voiced increasing frustration throughout 2019 with delays in the delivery of funds and the financial burdens being borne as a result of having to cash‑manage significant levels of expenditure. Métis governments also expressed concern that while they were experiencing an ever-expanding relationship with the Crown, involving an increasing number of federal departments and at least partially as a result of emerging priorities through the Permanent Bilateral Mechanisms established in 2017, the Crown-Métis team within CIRNAC had not grown in step to accommodate the increasing volume of policy and program areas. This increased volume of responsibility without increased staffing was seen by Métis governments as the cause of funding delays which threatened the achievements made over the same period.

In addition to the operational concerns on the part of recipients as a result of delays in the delivery of funds (on the part of C&PD often related to delays in decision making on proposals) across all three authorities is the risk of impacts on the relationship as a whole with Indigenous partners. As noted above, several historic milestone agreements have been reached with Métis governments and IROs during the evaluation period that have resulted in much improved goodwill that could be eroded should funding delays persist.

3.3 Performance: Alignment of Current Approach with Self-Determination, and a Renewed Relationship

Finding 13. Aside from gains (positive support to governing members and their membership systems made under the FICP Governance Program), the Department’s approach to IRO support is limited in its contribution to higher level government priorities of advancing Indigenous self-determination and renewing the relationship with Indigenous peoples.

Self-Determination

During the period covered by the evaluation, the Government of Canada committed to supporting the advancement of the self-determination of Indigenous peoples. The Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations was tasked in her mandate letter (October 2017 and renewed and re-affirmed in August 2018), to both "modernize our institutional structure and governance so that First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples can build capacity that supports implementation of their vision of self-determination" and "engage constructively and thoughtfully and add priorities to your agenda when appropriate." The evaluation team considers that the funding authorities could be said to contribute to Indigenous self-determination to the extent that they support IRO priorities and mandates.

The discretion of the Department to approve and reject C&PD funded proposals from BOC recipients is not adequately conducive to the principle of self-determination. According to interviews with CIRNAC staff, the projects that are most likely to be approved are the ones that best align with the Government of Canada's stated priorities. True self-determination would suggest that these organizations be able to articulate their own priorities, and that the Government would negotiate funding based on those articulated priorities.