Evaluation of the Northern Contaminated Sites Program

June 2021

Prepared by: Evaluation Branch

PDF Version (661 KB, 48 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Approach

- 3. Findings—Relevance

- 4. Findings—Efficiency

- 5. Findings—Effectiveness

- 6. Conclusions

- 7. Recommendations

- Appendix A: National Classification System for Contaminated Sites

- Appendix B: Northern Contaminated Sites Program Logic Model

- Appendix C: Evaluation Matrix

List of Acronyms

| AOC |

Aboriginal Opportunity Considerations |

|---|---|

| CIRNAC |

Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada |

| FCSAP |

Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan |

| FMRP |

Faro Mine Remediation Project |

| GBA Plus |

Gender-Based Analysis Plus |

| GMRP |

Giant Mine Remediation Project |

| NCSP |

Northern Contaminated Sites Program |

| NWT |

Northwest Territories |

| PSAB |

Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Businesses |

| PSPC |

Public Services and Procurement Canada |

| QRA |

Quantitative Risk Assessment |

Executive Summary

Canada discharges its responsibility to manage 167 contaminated sites located northFootnote 1 of the 60th parallel through the Northern Contaminated Sites Program (NCSP). NCSP is administered by the Northern Affairs Organization of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) and primarily funded through the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (FCSAP).

The program ensures that northern contaminated sites are managed to protect human health, safety and the environment for all Northerners by assessing and remediating contaminated sites, and supporting employment and training. This involves carrying out assessment, care and maintenance, remediation/risk management and monitoring activities on contaminated sites, while promoting socio-economic benefits to Northerners, particularly Indigenous peoples.

Purpose and Methods

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of the NCSP. The evaluation is required as per CIRNAC's Five-Year Evaluation Plan to ensure compliance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results.

The scope of the evaluation covered the period of 2014-15 through to 2019-2020, examining the issues of relevance, efficiency (program design and delivery) and effectiveness (achievement of expected results). During the planning and conduct of this evaluation, there was considerable transformation in the federal approach to the management of northern contaminated sites. In Budget 2019, the FCSAP was renewed for another 15 years, and a new program was announced, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. The new program was launched in 2020 to exclusively address the eight largest and highest-risk abandoned mines (i.e. Faro and Giant Mines) in the Yukon and NWT, with the remediation of the other contaminated sites in the North remaining under the responsibility NCSP. This evaluation was designed to inform the NCSP's successor program, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program.

Findings and Conclusions

Relevance

The evaluation found that NCSP was, is and will continue to be highly relevant as a means of addressing the needs and priorities related to contaminated site remediation, reconciliation, and socio-economic development in the North.

There is strong evidence of a continued need for NCSP. The program is the primary tool to address outstanding liability and risks to the environment and human health associated with contaminated sites north of the 60th parallel. The Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory lists 161 suspected or active federal contaminated sites in northern Canada under the custodianship of CIRNAC at the beginning of the evaluation period, April 1, 2014. Of these sites, 145 (90%) were active. More recent Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory data indicates that there were 167 suspected or active contaminated sites in northern Canada at the close of the evaluation period, March 31, 2018, of which 151 (90.4%) were active.

There was broad endorsement that reconciliation is the lens through which programs affecting Indigenous peoples and communities should be designed and delivered. Over the evaluation period, NCSP has taken positive and helpful steps to support reconciliation, however, these efforts have been restricted to very local solutions at specific points in time.

Overall, as a priority program to address Canada's policy objectives and expectations of Indigenous peoples and Northerners, the program should explore a way forward to ensure that reconciliation and the need for socio-economic development are fully incorporated into all aspects of the program.

Efficiency

NCSP has demonstrated to be flexible and adaptable, particularly at the project level, over the evaluation period.

There is evidence that the NCSP project management approach is generally viewed as sound, robust and flexible. The Giant Mine Working Group has been cited as an example within project management as a forum to maintain ongoing dialogue with stakeholders. As well, the program's peer review model is considered an international leading practice. It was noted that embracing common industry best practices more fully should be considered.

While meaningful consultation and engagement have the potential to support reconciliation and socio-economic development, and reduce overall project risk, there was little evidence that this had occurred over the evaluation period. Many external respondents expressed general dissatisfaction with consultation and engagement, and the appropriate human and financial resources to design and implement meaningful consultation and engagement were not apparent. The Giant Mine Remediation Project (GMRP) surface design, the Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) and socio-economic development strategy engagement processes were notable exceptions, which present scaling opportunities.

While contaminated site remediation offers billions in potential revenue to remediate contaminated sites and support socio-economic development of the North, there is limited evidence that this promise has been realized by Indigenous and northern communities and businesses. There are a number of barriers to achieving this potential. These are long-standing and well-known issues that require comprehensive response.

While improvements have been made in many areas over the evaluation period, there are opportunities to build on success to address long-standing issues, which will contribute to a more efficient and effective program.

Effectiveness

Evidence from both the performance data and interviewees suggests that during the evaluation period, the risks to human health and the environment from northern contaminated sites were being identified and addressed. For example, between April 2014 and March 31, 2018, sites in active remediation and long-term monitoring consistently increased. Additionally, sites rated very high or high maintained mitigation strategies in place over the same period. Interviewees expressed concern that Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems are not integrated into site environmental monitoring and risk management. It was repeatedly noted that there is a reliance of western science and engineering-based knowledge and skills, which do not necessarily incorporate Indigenous guidance and traditional knowledge.

While the target of 95 percent for expenditures that are liability reducing was exceeded during the evaluation period, the total liability of northern contaminated sites increased by $580 million (including Faro Mine Remediation Project (FMRP) and GMRP) or $110 million when these sites are excluded.

It is evident that NCSP has a strong focus on effectiveness, but the program is challenged to present a complete performance story. While project performance data is regularly collected, reported and shared, there is opportunity to tell a more comprehensive performance story.

Evaluation Recommendations

The following recommendations were derived from the evaluation's findings and conclusions.

- NCSP should be recalibrated using the lens of reconciliation. From the outset, all stakeholders should be jointly involved in the development of "NCSP of the future," from conceptualization and design, through to implementation, ongoing management, and monitoring and evaluation. Recommendations two and three, derive from this overarching recommendation.

- NCSP should strive to better understand the socio-economic needs of Indigenous and northern communities by working directly with communities at the project specification stage, to ensure that the socio-economic opportunities flowing to Indigenous and northern communities and businesses are maximized. This should include understanding the local realities, including what is realistically achievable; and, adapting federal procurement to the local realities of the North to better enable Indigenous and northern communities and businesses to competitively bid on procurement opportunities.

- NCSP should ensure that remediation projects, currently largely driven by western scientific, engineering and technical requirements, emphasize a more people-centered, public participation process driven by reconciliation.

- NCSP should fully embrace common industry project management best practices of front-end loading, stage-gating and earned value project management.

- NCSP should review the program performance measurement framework, to address limitations such as sequencing of outputs and outcomes, adequacy of outcome definitions, indicators and strength of targets.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Northern Contaminated Sites Program

1. Management Response

The Northern Contaminated Sites Program (NCSP) acknowledges the findings of the evaluation report and has provided an action plan to address its recommendations. As per the program's request during the planning phase of the evaluation, the evaluation team delivered a report that specifically investigates NCSP performance through the lens of reconciliation.

In the years following the evaluation's scope (2014-2015 to 2017-2018), NCSP has been extended through two sub-programs: the new Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program and the renewed Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. NCSP participated in engagement sessions with program stakeholders and Indigenous peoples to gather feedback on program performance and ensure the new programs are effective in meeting their objectives.

On April 1, 2020, NCSP launched the new Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation program to address the unique needs of the eight largest and highest risk mine reclamation projects in the North. Additionally, the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (FCSAP) program was renewed for Phase IV, which also began on April 1, 2020. FCSAP Phase IV includes commitments related to socio-economic performance, Indigenous engagement and increased prioritization of contaminated sites that impact Indigenous communities and Northerners.

These two programs have already begun addressing the recommendations identified in the evaluation. Several of these interventions have been implemented and are being monitored, whereas other actions remain under development. The evaluation's recommendations reinforce the importance of these actions and ongoing work to monitor their outcomes. These new programs also build upon the strengths of the program noted in the evaluation, including the program's sound, flexible and robust project management practices, to ensure that NCSP continues to be an effective and highly relevant means of addressing the needs and priorities related to contaminated site remediation, reconciliation and socio-economic development in the North.

The responses below are realistic, actionable responses to the recommendations. While NCSP is involved in various work projects that address the gaps identified by the evaluation, the selected list of actions were deemed to be the most pertinent and measurable.

Many of the responses are planned for completion by March 31, 2025. This date marks the end of Phase IV of the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan. It is possible that Phase IV could be extended, although an extension would likely be accompanied by additional policy commitments. For this reason, NCSP has decided to limit the maximum duration of the action's plan scope to March 31, 2025.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NCSP should be recalibrated using the lens of reconciliation. From the outset, all stakeholders should be jointly involved in the development of "NCSP of the future," from conceptualization and design, through to implementation, ongoing management, and monitoring and evaluation. Recommendations two and three, derive from this overarching recommendation. | With the launch of the new Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program and the renewal of FCSAP Phase IV, several aspects of the program have been recalibrated using the lens of reconciliation. Additionally, NCSP projects have co-developed governance agreements and socio-economic strategies with Indigenous and territorial partners that promote the full project lifecycle involvement of Indigenous communities and Northerners. The Giant Mine Remediation Project has co-developed a socio-economic strategy and associated socio-economic implementation plan. Under this strategy, the project established a socio-economic working group and advisory body and funded staff, training, and a Business Preparedness conference for Indigenous partners and northern stakeholders in 2020-21. Similarly, the Faro Mine Remediation Project is co-developing a Socio-Economic Framework in 2021-22 to guide the delivery of socio-economic benefits, and has already made funding available to several Indigenous partners to participate in its development. To build on these successes, the program is finalizing a NCSP Socio-economic Strategy, with plans for implementation in 2021-22. This evergreen strategy establishes a program-wide approach to delivering socio-economic benefits to Indigenous peoples and other Northern stakeholders. The implementation of the socio-economic strategy will support NCSP's commitment to engagement with Indigenous peoples and Northerners throughout the project lifecycle, as project specific socio-economic objectives are co-developed or based on local priorities. The inclusion of project stakeholders and rights-holders in the development of these strategies helps to ensure that socio-economic benefits are maximized. NCSP is also developing updated Northern Procurement Guidance in partnership with Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), that will emphasize the importance of early and ongoing engagement throughout the procurement process. This new guidance will be developed in close collaboration with PSPC. The program has committed to completing this guidance by March 31, 2022. Much like the socio-economic strategy, this guidance will be evergreen, and require regular updates. NCSP will also continue to support the FCSAP secretariat's commitment to develop new federal Indigenous engagement guidance during FCSAP Phase IV. |

Senior Director, Northern Contaminated Sites Branch, Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: April 2020 Completion: March 2023, with ongoing updates |

| 2. NCSP should strive to better understand the socio-economic needs of Indigenous and northern communities by working directly with communities at the project specification stage, to ensure that the socio-economic opportunities flowing to Indigenous and northern communities and businesses are maximized. This should include understanding the local realities, including what is realistically achievable; and, adapting federal procurement to the local realities of the North to better enable Indigenous and northern communities and businesses to competitively bid on procurement opportunities. | Since the evaluation period, NCSP has co-developed a Socio-economic Strategy and Implementation Plan with Indigenous partners for the Giant Mine Remediation Project and a Project Governance Agreement with the Délı̨nę Got'ı̨nę Government for the Great Bear Lake Remediation Project. The Giant and Faro Mine Remediation Projects have also conducted Labour Resource Studies to maximize local resource participation in the projects. As noted above, work is also underway on an overarching NCSP Socio-economic Strategy in 2021-22. While the program strategy will bring consistency to the socio-economic approaches across projects and regions, project specific strategies will be adapted to regional and community distinctions. One of the goals of this strategy is to support expanded use of procurement approaches that support Indigenous and Northern involvement in projects. Additionally, NCSP is working with PSPC to update the program's Northern Procurement Guidance in 2021-22, linked to the program's socio-economic strategy. New procurement guidance will support program staff and PSPC service delivery partners in ensuring that procurement approaches for NCSP projects are flexible and relevant to the local realities of the North, and provide guidance on Indigenous an Northern procurement tools. This work is a commitment under FCSAP Phase IV, and will be used by other federal partners as the basis of procurement guidance for other FCSAP custodians managing federal contaminated sites in the North. |

Senior Director, Northern Contaminated Sites Branch, Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: April 2020 Completion: March 2025 |

3. NCSP should ensure that remediation projects, currently largely driven by western scientific, engineering and technical requirements, emphasize a more people-centered, public participation process driven by reconciliation. |

With the renewal of the FCSAP program on April 1, 2020, new guidance prioritizes all contaminated sites located in Indigenous communities and in the North. As a result, many sites in the NCSP portfolio are now eligible for funding in Phase IV and can be elevated as priorities in the work plan to support Indigenous reconciliation. In addition, NCSP projects increasingly include Traditional Knowledge studies as part of the assessment stage. NCSP will continue to support greater inclusion of traditional knowledge into project planning and implementation as a best practice. For example, the Giant Mine Remediation project has completed a Traditional Knowledge study and many project decisions have been influenced by the valuable Traditional Knowledge that community members have shared in project engagement sessions, technical meetings and workshops. The project utilized this Traditional Knowledge from community members and elders to inform the design and development of the water license package, including the Closure and Reclamation Plan, Surface Design Engagement, Quantitative Risk Assessment, and Archaeological Impact Assessment. The team will continue to incorporate Indigenous Knowledge into various facets of the project in the future. |

Senior Director, Northern Contaminated Sites Branch, Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: April 2021 Completion: March 2023 |

| 4. NCSP should fully embrace common industry project management best practices of front-end loading, stage-gating and earned value project management. | Since the evaluation period, NCSP has developed detailed regional and project-specific dashboards to highlight scope, schedule and budget changes and elevate developing problems, non-compliances and non-performance to senior management. These reporting tools will allow the program to better adopt the principle of "earned value project management." NCSP will continue to support the FCSAP secretariat in refining the federal work planning process to promote front-end loading of contaminated sites projects. The FCSAP program is also finalizing FCSAP Phase IV operational guidance for contaminated sites project managers, including project management best practices such as project readiness assessments. The NCSP has also developed and implemented Requirements for the Management of Northern Contaminated Sites, whereby project requirements must be fulfilled in order to access budget allocations and to progress from one project stage to the next. This process aligns with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Guide to Project Gating by providing formal opportunities throughout the project life cycle to take stock of the accomplishments to date, and to ensure that there is a clear and viable path to achieving the desired project outcomes. The new NCSP Quality Assurance Office in the Policy and Program Management Directorate, will be responsible for routine checks and readiness assessments on NCSP projects. Large projects are also to follow the NCSP Major Projects Delivery Model. |

Senior Director, Northern Contaminated Sites Branch, Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: April 2021 Completion: March 2025 |

| 5. NCSP should review the program performance measurement framework, to address limitations such as sequencing of outputs and outcomes, adequacy of outcome definitions, indicators and strength of targets. | Through the renewal of the FCSAP program and the start of Northern Abandoned Mine Remediation Program on April 1, 2020, NCSP has committed to a new set of performance indicators and targets that will better represent the program's performance story. There are now indicators that capture socio-economic factors such as employment and training for Indigenous peoples, northerners and women, and sub-contracts going to Indigenous and Northern firms. The NCSP Performance Information Profile has been updated to reflect these changes, and will be reviewed by Northern Affairs Organization's Senior Result Advisor to ensure the quality of information presented. |

Senior Director, Northern Contaminated Sites Branch, Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: April 2020 Completion: March 2021, with ongoing updates |

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Northern contaminated sites originated primarily from mining, petroleum and government military activity that occurred more than 50 years ago, when the environmental impacts of these activities were not fully understood. In addition to posing risks to human health and safety, and to the fragile northern environment, the sites represent a significant financial liability to the Crown.

The federal approach to contaminated sites, employs a 10-step process,Footnote 2 used by custodians such as Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) to address contaminated sites. Sites suspected of contamination are initially assessed to determine if risks to human health and the environment exceed guidelines. On the basis of the assessment results, sites are then classified and prioritized according to the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment's National Classification System for Contaminated Sites (Appendix A).

There are 2,644 northern contaminated sites in the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, with CIRNAC as the custodian of 167 sites (Table 1).

| Site Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory | Suspected | Active | Closed | Total |

| Yukon | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Northwest Territories | 6 | 76 | 0 | 82 |

| Nunavut | 10 | 68 | 0 | 78 |

| Total | 16 | 151 | 0 | 167 |

1.2 Expected Results

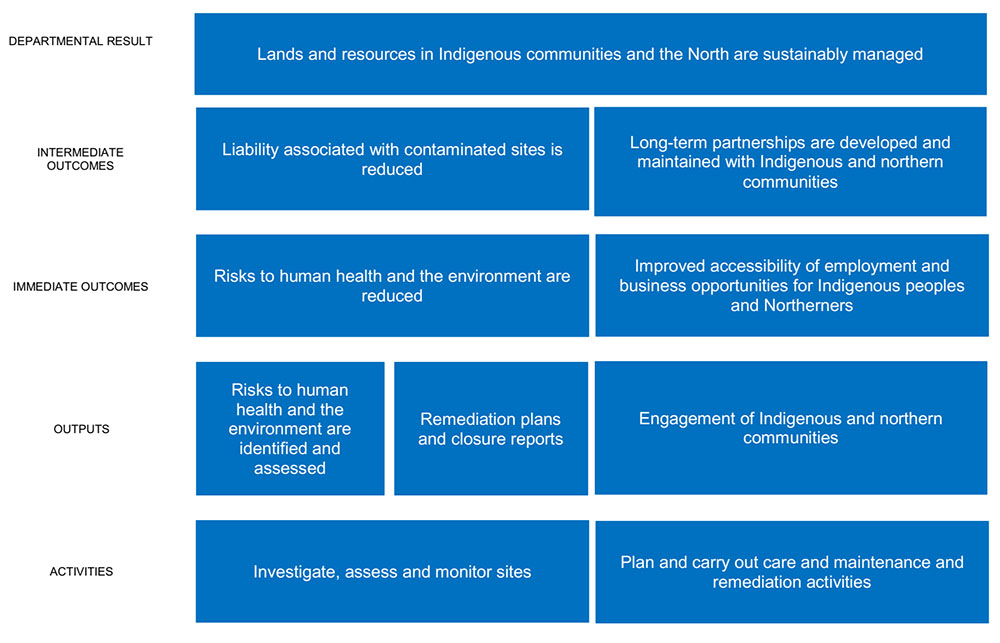

The Northern Contaminated Sites Program (NCSP) contributes to CIRNAC's core responsibility Community and Regional Development ensuring that northern contaminated sites are managed to protect human health, safety and the environment for all Northerners by assessing and remediating contaminated sites, and supporting employment and training. This involves carrying out assessment, care and maintenance, remediation/risk management and monitoring activities on contaminated sites, while promoting socio-economic benefits to Northerners, particularly Indigenous peoples.

The complete logic model for the program can be found in Appendix B.

1.3 Governance

| Key Positions | Roles and Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Assistant Deputy Minister |

|

| NCSP Executive Director |

|

| Regional Director General |

|

| CommitteeFootnote 4 | Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Northern Management Committee |

|

| NCSP Executive General/ Regional Director General Committee |

|

| NCSP Directors Committee |

|

| Project Advisory Committee |

|

| Environment, Health and Safety Working Group |

|

At the project level (individual contaminated sites) there can be several additional governance bodies with a variety of mandates, roles and responsibilities and membership. This can include strategic/oversight bodies with senior federal, Indigenous and sometimes territorial representation, committees and working groups are more operational in nature, with mid-level management and working-level federal, Indigenous and sometimes territorial representation.

1.4 Funding and Resources

NCSP is primarily funded through Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (FCSAP), which was established in 2005 as a 15-year program. In Budget 2019, FCSAP was renewed for another 15 years (2020 to 2034) with $1.16 billion announced for the first five years. FCSAP is administered jointly by Environment and Climate Change Canada and Treasury Board Secretariat.

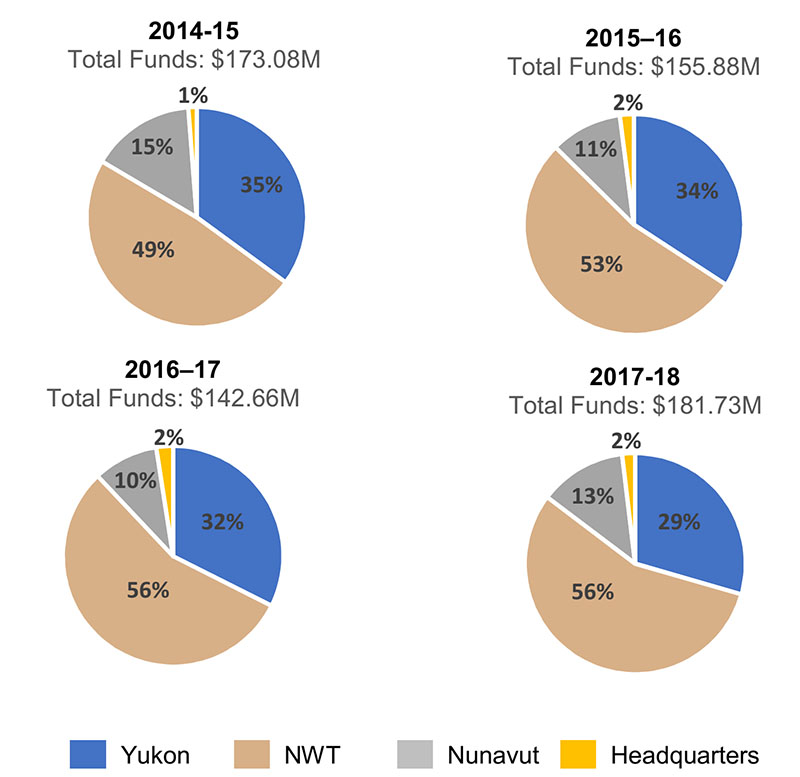

Figure 1: NCSP Budget Distribution, by Year

Text alternative for Figure 1: NCSP Budget Distribution, by Year

Figure 1 shows four pie charts corresponding to NCSP’s budget distributions for four consecutive years.

The first pie chart shows that a total budget of $173.08M was allocated for the 2014-15 period. Of these, 1% was allocated to Headquarters, 35% was allocated to Yukon, 49% was allocated to NWT, and 15% was allocated to Nunavut.

The second pie chart shows that a total budget of $155.88M was allocated for the 2015-16 period. Of these, 2% was allocated to Headquarters, 34% was allocated to Yukon, 53% was allocated to NWT, and 11% was allocated to Nunavut.

The third pie chart shows that a total budget of $142.66M was allocated for the 2016-17 period. Of these, 2% was allocated to Headquarters, 32% was allocated to Yukon, 56% was allocated to NWT, and 10% was allocated to Nunavut.

The fourth pie chart shows that a total budget of $181.73M was allocated for the 2017-18 period. Of these, 2% was allocated to Headquarters, 29% was allocated to Yukon, 56% was allocated to NWT, and 13% was allocated to Nunavut.

Over the evaluation period, FCSAP was responsible for the total expenditures for both the Giant Mine Remediation Project (GMRP) and the Faro Mine Remediation Program (FMRP) totalling $364.16 million and for all other contaminated sites in the North, FCSAP invested $231.28 million. CIRNAC invested $32.71 million to support the activities of contaminated sites remediation for all other projects.

| Directorate | Fiscal Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | |

| Faro Directorate | 5.6 | 7.5 | 10.2 | 12.5 |

| Giant Directorate | 16.6 | 19.8 | 19.7 | 19.6 |

| Program Management Directorate | 14.9 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 16.2 |

| Project Technical Office | 2.7 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 8.1 |

| Total | 39.8 | 50.4 | 54.6 | 56.4 |

2. Evaluation Approach

2.1 Objectives and Scope

The Evaluation of NCSP is required as per CIRNAC's Five-Year Evaluation Plan to ensure compliance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results. Since NCSP includes ongoing programs of grants and contributions, the evaluation is also subject to Section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The scope of the evaluation covered the period of 2014-15 through to 2019-2020, examining the issues of relevance, efficiency (program design and delivery) and effectiveness (achievement of expected results). During the planning and conduct of this evaluation, considerable transformation was underway to the federal approach to the management of northern contaminated sites, including major reforms to the NCSP program. The reforms that were underway to the NCSP included modifications to performance indicators and targets. As a result of the transformation of the NCSP, this evaluation focussed on data that was available up until 2018 to ensure consistency in analysis. The evaluation was designed to inform the NCSP's successor program, the Northern Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program. The new program was announced in 2019 and launched in 2020 to exclusively address the eight largest and highest-risk abandoned mines (i.e. Faro and Giant Mines) in the Yukon and NWT, with the remediation of the other contaminated sites in the North remaining under the responsibility NCSP.

The evaluation assessed the value of the combined investments of CIRNAC and FCSAP through the lens of relevance, efficiency (program design and delivery) and effectiveness (achievement of expected results). Specifically, FCSAP annual resources to the NCSP to assist in the delivery of the Contaminated Sites program as remediation costs for most sites are cost-shared by FCSAP. Contributions are made from CIRNAC's resource base to satisfy the shared funding requirements associated with the FCSAP program (85% FCSAP and 15% CIRNAC) and to address departmental obligations for sites not funded under the FCSAP.

The need for the evaluation was further influenced by drivers, including the programs high to very high program risks related to:

- Challenges with procurement, which lead to project delays, legal challenges and an inability to achieve program objectives;

- Challenges in achieving targets for the delivery of social and economic benefits to Indigenous peoples and Northerners through NCSP activities;

- Expanding program scope as new contaminated sites are identified contaminated sites.

2.2 Methods

The evaluation examined questions presented in the Evaluation Matrix (Appendix C). It used multiple lines of inquiry, both qualitative and quantitative methods, to triangulate and mitigate limitations.

| Document Review | Key Informant Interviews (n=21) | Case Studies Interviews (n=45) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Limitation | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Findings—Relevance

3.1 Continued Need for the Program

Key Findings: There is a continued need for the immediate outcome to address the outstanding liability and risks to the environment and human health associated with contaminated sites north of the 60th parallel.

NCSP is an important contributor to reconcilliation.

NCSP is an important contributor to support the socio-economic development of northern communities to address longstanding inequalities.

Continued Need to Address NCSP Outcomes

Continued Need for Site Remediation

There is strong evidence of a continued need for NCSP to address outstanding liability and risks to the environment and human health associated with contaminated sites north of the 60th parallel.

The Federal Contaminated Sites InventoryFootnote 5 lists 161 suspected or active federal contaminated sites in northern Canada under the custodianship of CIRNAC at the beginning of the evaluation period, April 1, 2014. Of these sites, 145 (90%) were active. More recent, the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory data indicates that there were 167 suspected or active contaminated sites in northern Canada at the close of the evaluation period, March 31, 2018, of which 151 (90.4%) were active.

The 2018 FCSAP evaluation concluded, "There is a clear ongoing need for FCSAP or a similar program to address outstanding liability and risks to the environment and human health associated with federal contaminated sites. Furthermore, the need for long-term monitoring at some sites, along with growing recognition of the need to address emerging contaminants, attest to the program's ongoing relevance"Footnote 6. The evaluation also noted the mobility and toxicity of many contaminants and the resulting increasing risk over time to human health and the environment. It also noted emerging contaminants that may generate unexpected increases in federal liabilities.

In three of the four years within the scope of the evaluation, the program received funding enhancements. Budget 2019 announced several efforts to strengthen Canada's commitment to remediating contaminated sites, including:

- FCSAP renewal for another 15 years (2020 to 2034) with an investment of $1.16 billion for the first five years; and

- Creation of the Northern Abandon Mine Reclamation Program, investing $2.2 billion over 15 years starting in 2020–21, to exclusively address the eight largest and highest-risk abandoned mines in the Yukon and NWT, with the remediation of the other contaminated sites in the North remaining under the responsibility of CIRNAC through NCSP.

Looking ahead, while new sites are being identified, which are the result of historical contamination and there are new contaminants that are of concern, the 2018 FCSAP Evaluation observed that modern federal legislation and policies, and increased environmental awareness, prevent or greatly reduce the likelihood of creating new contaminated sites. Higher standards for financial and environmental procedures at new mines and other industrial developments are now the industry norm, and the current regulatory framework also mitigates the costs of decommissioning and reclamation in the event of insolvency.

Contribution to Reconciliation

There is strong evidence that NCSP is an important contributor to reconciliation, which remains a priority of the federal government.

From the federal perspective, reconciliation has been a priority over the evaluation period, and remains so. In 2016, Canada officially removed its objector status to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, widely viewed as an important step towards reconciliation.Footnote 7 The "Principles Respecting the Government of Canada's Relationship with Indigenous Peoples" is intended to guide the federal government's relationship with Indigenous peoples. Since 2015, successive speeches from the Throne, budget plans and mandate letters have signalled the continued need for reconciliation. Budget 2019 devoted an entire chapter to the topic through several measures, including "Redressing Past Wrongs and Advancing Self‑Determination" and "Healthy, Safe and Resilient Indigenous Communities," both pertinent to the remediation of contaminated sites in the North. A priority of Canada's new Arctic and Northern Policy Framework 2019 is to "advance reconciliation and improve relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples."

The 2018 FCSAP Evaluation found that the program "is widely seen by internal and external stakeholders as an important contributor to the reconciliation agenda, since it helps to satisfy the federal government's obligation to address contamination in Indigenous communities, and generates socio-economic benefits for Indigenous peoples." While key informant interviews and case study interviewees generally agreed with this statement, there was a higher level of success ascribed to the operationalization of reconciliation by internal respondents than external respondents.

Canada's reconciliation intentions were described by some respondents as opaque and not institutionalized. They cited the lack of a reconciliation strategy and operational guidelines to advance reconciliation through NCSP, and that responsibility for implementing reconciliation was delegated to the program manager level without vehicles for the input of Indigenous parties.

Although the Canada School of Public Service offers reconciliation training to public servants, interviewees suggested that there be opportunities to interact with Indigenous people "in their communities" to "hear individual stories" and "build empathy." It is notable that none of the interviewees cited the federal government's "Principles Respecting the Government of Canada's Relationship with Indigenous Peoples", intended to help achieve reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, or CIRNAC's "Guidance on Engagement Activities and Costing Throughout a Contaminated Site Project Lifecycle"Footnote 8, which references these principles.

The 2018 FCSAP Evaluation recommended, "increasing alignment with the reconciliation agenda through measures such as increased engagement with Indigenous communities; improved guidance and training for custodians on collaborating and engaging with Indigenous communities; procurement practices that promote greater participation by Indigenous peoples; and explicit consideration of factors of importance to Indigenous peoples." The findings of the NCSP Evaluation support this recommendation.

Continued Need for Socio-economic Benefits in the North

There is strong evidence that NCSP is an important contributor to the efforts surrounding the federal government's priority of socio-economic development of the North.

The North has experienced "long-standing inequalities in transportation, energy, communications, employment, community infrastructure, health and education" and lack of "access to the same services, opportunities, and standards of living as those enjoyed by other Canadians." Across most socio-economic indicators (e.g., education, employment, income), territorial performance is lower than the Canadian average. The Conference Board of Canada identifies geography, demography and substantial Indigenous populations facing distinct historical, cultural and socio‑economic challenges as some of the factors contributing to these disparities.Footnote 9

Successive federal strategies (e.g., Northern Strategy 2009, Statement on Canada's Arctic Foreign Policy 2010 and Canada's Arctic and Northern Policy Framework 2019) and successive budgets since 2013 have supported socio-economic development in northern communities. The Arctic and Northern Policy Framework outlines "a shared vision of the future where northern and Arctic people are thriving, strong and safe", with priorities related to people and communities, science and environment, economic development and infrastructure.

3.2 Alignment With Government Priorities

Key Findings: NCSP is well-aligned with Government of Canada priorities. The program is a major partner in implementing FCSAP, thereby contributing to "Canada’s overall goals with respect to contaminated sites."

Alignment with Government Priorities and CIRNAC Mandate

Alignment with Government Priorities

NCSP is well aligned with federal government priorities, and contaminated sites remain the responsibility of the Government of Canada.

NCSP aligns with the following federal strategies for the North:

- Canada's Arctic and Northern Policy Framework;

- Canada's Economic Action Plan; and

- Initiatives and programs of the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency.

NCSP aligns with commitments outlined in existing and new Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements and devolution of land and resources in the Yukon, NWT and Nunavut.

Policy documents for FCSAP Phases II and III establish links to government policy areas, which are strongly represented by NCSP, including health, science and technology, Indigenous employment and training, economic development, and the Northern Strategy. The policy document for Phase III emphasizes that a high proportion of FCSAP funding directed to northern sites demonstrates Canada's commitment to the Northern Strategy and devolution of land management. In its assessment of FCSAP alignment with government priorities, and federal roles and responsibilities for contaminated sites in Canada, the 2018 FCSAP Evaluation found clear alignment. It also established alignment with and supports, "for existing federal legislation such as the Fisheries Act, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, the Species at Risk Act…[and] Section 64(2) of the Financial Administration Act [that] stipulates that the Public Accounts of Canada should include environmental liabilities."

Alignment with CIRNAC Mandate

NCSP is strongly aligned with the mandate of CIRNAC as observed in the Ministers' Mandate Letters, the CIRNAC Departmental Plan and earlier reports on plans and priorities.

The activities of NCSP are aligned to CIRNAC's core responsibility for community and regional development and the departmental result land and resources in Indigenous communities and the North are sustainably managed. The expected results aligned to the program in 2014-15 through to 2016-17 were "Contaminated sites are managed to ensure the protection of human health and the safety of the environment while bringing economic benefits to the North," and since 2017–18, it has been "Environmental stewardship of contaminated sites is responsible and sustainable."

4. Findings—Efficiency

4.1 Governance

Key Findings: NCSP has displayed flexibility and adaptability introducing different solutions to improve governance, reflecting regional and local contexts. In this regard, the program has met with considerable success applying the lessons learned, particularly at the project level. However, the overall governance structure is generally viewed as being overly complex.

Extent the Governance Structure Contributes to the Achievement of NCSP Outcomes

Clarity, Appropriateness and Efficiency of the Governance Structure

NCSP governance has evolved over the evaluation period, demonstrating it to be flexible and adaptable, particularly at the project level, by being responsive to local context and building on lessons learned.

Flexibility and Adaptability of Governance

There have been ongoing efforts to improve NCSP governance, including the 2014 establishment of the Northern Contaminated Sites Branch. At the regional and project level, governance is structured in accordance with local contexts and individual sites, and is reportedly effective, displaying flexibility and adaptability. This was found to be particularly so at the project level, which was described as pragmatic. There was a high level of agreement amongst internal interviewees that NCSP governance had improved since the creation of the Branch.

There has been some experimentation with the governance of northern contaminated site remediation projects. For example, Elsa Reclamation and Development Company Ltd., a unit of Alexco Resource Corp., owns the former assets of United Keno Hill Mine. It is responsible, under a funding agreement with Canada and the Yukon Government, for the care and maintenance of the properties and the eventual reclamation and closure of the sites. A separate subsidiary of Alexco Resource Corp, Alexco Keno Hill Mining Corp., is incorporated for the purpose of mineral extraction on other areas of the site, with revenue from the production mine offsetting the costs of the remediation. Broad satisfaction was expressed by key informants and case study interviewees with these governance arrangements.

Data analysis suggests that the governance approach and structure can be overly complex. It was found that external interviewees do not have a clear understanding of NCSP governance and individual remediation projects. There was also consensus by external respondents that the various committees, working groups and consultative bodies for the FMRP and GMRP were too numerous, overly bureaucratic and over-regulated.

Clarity of Roles and Responsibilities

NCSP is supported by multiple stakeholders, each playing an important role in the remediation of contaminated sites. Roles and responsibilities within the program (headquarters, regional offices and project level), were found to be well-defined. It was suggested, however, that the technical, procurement and contracting authorities between CIRNAC and PSPC were unclear, and roles and responsibilities imprecisely defined.

| Technical Authorities | Procurement Authorities | Contracting Authorities |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

For major projects, such as the GMRP, CIRNAC is designated as the technical and procurement authority, with PSPC designated as the contracting authority, however, it was identified by key informants that there are instances when PSPC acted as the technical authority. For example, PSPC drafted the Terms of Reference for the GMRP Construction Manager, a role normally fulfilled by the technical authority, which was then deemed inadequate by CIRNAC. At the regional office level and with other contaminated site remediation projects, it has been reported by PSPC and CIRNAC that the authorities are well-defined.

Evidence also suggests that there is differing views of contaminated site remediation in the Yukon between the Yukon Government, CIRNAC's Yukon Regional Office and NCSP Headquarters. Interviewees cited poor direction and confusion about roles related to the development of remediation plans, which has apparently led to substantial project delays, resulting in high project costs and an increase in liability.

Effectiveness of Decision-making

Given the complexity of NCSP governance, involving multiple stakeholders from national, regional and local levels, and complex operating conditions, relatively few decision-making issues were identified. The Directors Committee reportedly experiences difficulty separating the needs and priorities of the program as a whole over those of individual regions and projects. While the effectiveness of the Project Advisory Committee was questioned, with decisions made by the Project Advisory Committee "often reversed [within weeks] by the Program Technical Office officer responsible for projects", overriding the region, with reasons for decisions rarely shared.

With respect to the major projects, the FMRP governance structure was described as a "light" version of that for the GMRP, smaller and nimbler. With this structure, the project includes broad representation from federal, territorial and Indigenous governments at the working-level, meeting regularly to discuss operational issues or more formalized as the Technical Review Committee. Given the flatter governance structure, communication is reportedly to be effective across levels, and decision-making is perceived to be efficient.

4.2 Project Management

Key Findings: The NCSP project management approach is viewed as sound, robust and flexible. However, the program has not fully embraced common industry project management best practices, such as: front-end loading; stage gating; and earned value project management.

The peer review model is regarded as an international leading practice.

Contaminated site remediation remains primarily a technical exercise, without including sufficient consultation, engagement and socio-economic expertise and Indigenous representation. The notable exceptions to this are the GMRP surface design and QRA, which were successful in all aspects.

Extent Project Management Contributes to the Achievement of NCSP Outcomes

Utility of the Project Management Approach

There is good evidence that the NCSP project management approach is sound, robust and flexible and contributes to the success of NCSP. Project management is supported by appropriate project management policies, procedures, software and systems, and communities of experts. There are a few notable exceptions to this. There has been some reticence to fully embrace common industry project management best practices. Remediation also remains a primarily technical exercise, and project teams do not have adequate consultation, engagement and socio-economic expertise and Indigenous background.

Maintaining an Ongoing Presence in the Field

The NCSP project team maintains an ongoing presence and involvement in the regions. Interviewees cited this as a means to gain first-hand understanding of regional and local nuances and challenges, build relationships and trust with Indigenous governments and partners, and address risks as they arise.

Maintaining Ongoing Dialogue With Stakeholders

Ongoing dialogue with stakeholders is an important project management tool. For example, the Giant Mine Working Group, formed in 2013, was identified by interviewees as a helpful forum for interested parties to discuss and make recommendations on technical, operational and project activities regarding the remediation. The working group, co-chaired by the Government of Northwest Territories and CIRNAC meets monthly with a membership of federal government departments, Indigenous and municipal governments and a local social justice coalition.

The Giant Mine Oversight Board independently monitors, promotes, advises and broadly advocates the responsible management of the GMRP. Interviewees identified the Board as a second useful mechanism to encourage dialogue among stakeholders.

Recognizing the Value of Partnering and Collaboration

Working with the territorial governments, partnering with Indigenous parties, and being transparent and accountable in these relationships are valuable practices supporting effective project management. For example, the collaborative United Keno Hill Mine design and development process involving and seeking support from the First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun throughout the process. Adequate and early stakeholder consultation and engagement were identified as a key success factor, with consultation and engagement viewed as key inputs in the process of project definition.

Visioning to Agree on the Path Forward

External interviewees observed that visioning is a common practice on other files, but has rarely been used in contaminated site remediation projects. The external interviewees reported having a perception that CIRNAC was reluctant to integrate the visioning in the FMRP environmental assessment process.

Contaminated Site Remediation is Primarily Viewed as a Technical Exercise

Contaminated site remediation is undertaken primarily as a technical exercise, focussing on engineering and environmental matters to the exclusion of the affected people and communities and socio-economic aspects. Identifying and incorporating reconciliation considerations into contaminated site remediation projects are not widespread practices. Project teams are reportedly largely staffed by scientific, engineering and other technical experts. External interviewees were critical about the knowledge and skills related to socio-economic, consultation and engagement provided by project teams, and noted the lack of Indigenous representation on project teams. Interviewees recommended moving projects away from a technical orientation to a more people-centred orientation.

The Peer Review Model

The peer review practices use international external experts to review the technical merit of the remediation conceptual design and solutions (e.g., environmental and engineering solutions). The model is considered an international leading practice. Caution was noted that unless other traditional project checks and balances are used, the peer review process serves as the primary gate to sanction project progress. It was also noted that the peer review process should be extended to other points of remediation projects, such as the environmental, consultation and engagement aspects.

Limited Adoption of Industry Project Management Best Practices

Industry project management best practices, such as front-end loading, stage-gating and earned value project management, have not been fully applied to contaminated site remediation projects.

It was suggested that the program should adopt three key industry best practicesFootnote 10.

- Front-end loading: "energy, efforts, people, and resources" are focussed in the early days of the project.

- During the project definition and planning stage, when it is still inexpensive to make changes, compared to the later implementation and construction stages, where any change can be high impact in terms of cost and schedule delays.

- This approach, while included in the Major Project Standards and Guidance Manual, would require enhanced training within the program to support successful implementation.

- Stage-gate process: included in the Corporate Procedures Manual and Major Project Standards and Guidance Manual is only partially implemented by NCSP.

- Checks and readiness assessments should be increased as those in place tended to address developing problems.

- Earned value project management: integrates project scope, time and costs as a single system has the advantage of detecting, early on, indicators of non-compliance and non‑performance, making it very valuable especially in complex projects.

- Earned value would address the widely cited practice within NCSP of re-base lining project work schedules combined with an institutional culture that avoids reporting negative project performance.

- The concept is well-established internationally. For example, the federal United States infrastructure budget is built around the concept of earned value, and project award and execution will not advance unless the team has proven expertise in earned value managementFootnote 11.

Impact of Annual Planning and Budgeting on Multiyear Project and Program Management

The fundamental scope, scale and contextual differences of contaminated site remediation in the North compared to the South renders the five-year funding cycle of FCSAP a substantial challenge for NCSP. Needs of remediation projects in the North are more consistent with an envelope-based approach to funding as opposed to annual allocation.

The unpredictable and constrained operating environment of the North was cited by interviewees as particular challenges. For example, it was noted that it is difficult to adhere to rigid project planning in the North noting that flexibility is more required (e.g., expenses associated with logistics are a much more important factor than in the South) reflecting the unique context of site remediation not experienced south of the 60th parallel. Moreover, interviewees explained that contaminated site remediation projects face a wide range of risks (e.g., regulatory, engagement, climate change and northern context), and while these risks are well documented, and project managers are aware of, manage and adapt to them, neither project plans nor budgets comprehensively reflect risks. Consequently, at the portfolio level, risks cannot be proactively managed. This is exacerbated by the annual budget approval process, which poses a challenge for project management across multiple years.

The 2018 FCSAP Evaluation identified climate and geography as important drivers of project costs, which can be higher than average due to the shorter field season, the effect of the extreme cold on equipment and the remoteness of contaminated sites without road access. These operating conditions were identified by NCSP evaluation interviewees as factors requiring budget flexibility. The lack of multi-year funding was identified by the 2018 FCSAP Evaluation as a challenge, particularly affecting the pace and progress of work at larger sites. However, the evaluation did not find evidence of how widespread or consequential this challenge was for overall FCSAP efficiency.

Limited Project Resourcing

It was suggested that moving the funding decision-making process to NCSP Headquarters in 2014 is the reason for budgeting decisions being made without full appreciation of the implications for smaller regional projects. It was noted by interviews that the change has broader implications in the North because budgets require more flexibility due to the unpredictable weather. It was further noted that while NCSP wide budget cuts initially started with discussion of a 15% holdback, an additional 5% cut was also required with regional offices struggling to manage these budget reductions internally.

Staffing and available expertise were identified as issues by respondents. It was expressed that the larger (i.e., FMRP and GMRP) remediation may not be inadequately resourced and the scope of available expertise, limiting the front-end loading needs of these projects. The capacity of the Program Technical Office was also identified as an issue. It was suggested that project officers are responsible for too many sites to offer sound advice with only crisis situation receiving full consideration. Additionally, it was expressed that there's a need to build more environmental, health and safety capacity within NCSP.

4.3 Performance Data

Key Findings: The quality of performance data is limited by challenges, such as quality of contractor data; the accessibility of project status updates; and absence of performance targets.

Extent Performance Data are Collected and Reported

Collection and Reporting of Performance Data

While there is evidence that NCSP performance data is regularly collected, reported and shared with stakeholders internal and external to NCSP, there are issues with its comprehensiveness.

Since 2014, performance measurement for NCSP has been guided by two frameworks — the Performance Measurement Strategy and the Program Information Profile. Many of the indicators are the same or similar in nature, however, those in the Performance Measurement Strategy are raw counts, while those in the Performance Information Profile are expressed in terms of progress against targets.

Challenges with liability and reporting were commonly raised by interviewees. For example, the practice of "zeroing out" liability when sites move into monitoring was flagged. Respondents for the 2018 FCSAP Evaluation identified challenges around the measurement and estimation of remediation liabilities, including shifts in the guidance provided by the Treasury Board Secretariat and inconsistency among custodians in carrying out these activities. NCSP evaluation interviewees also indicated that risk reporting was conducted only to meet the minimum due diligence requirements, whereas a more fulsome approach would be required to reflect risk as a driver of project cost. It was noted that the recent simplification of quarterly reports eliminated reporting the most important project risks, which this respondent recommended reintroducing. The 2018 FCSAP Evaluation recommended improving the program's ability to "report on its contribution to reducing risk to the environment and human health, which is arguably its most important outcome, in a way that resonates with Canadians."

Interviewees made several suggestions for improved performance data, including earned value, project staffing (numbers, gender and Indigenous), community and Indigenous involvement, training, environment, health, and safety. Some interviewees suggested more comprehensive collection of cost information at a detailed level (e.g., cost per cubic meter to move tailings one kilometre). A detailed database of this nature, with assumptions and site locations, would be of particular assistance at the conceptual phases of remediation projects. It was suggested that the Program Technical Office would be the appropriate organization to develop and maintain such a database. Reviewing the quality of contractors' data on suppliers and employees was also recommended, as was the tracking of Aboriginal Opportunity Considerations (AOC) commitments.

Sharing of Performance Data with Partners and Other Stakeholders

Based upon the document review, there is limited sharing of program performance data with external stakeholders, in particular Indigenous partners.

| Information shared with Indigenous partner (project level) |

Information shared with general public (departmental website) |

|---|---|

|

|

External interviewees identified that how information is shared could be improved by offering project status updates that are:

- Translated into Indigenous languages;

- Written using straightforward terms;

- Providing opportunity for community dialogue; and

- Providing paper and video copies because there is a lack of access to computers and/or the Internet.

It was further emphasized the importance of ensuring that Elders understand project updates. Elders are critical to successful engagement activities since they advise their communities. If the Elders are unable to participate meaningfully in engagement activities, the support and advancement of a project could be impacted. The GMRP was identified as a project that was more accommodating in this respect, with videos in Indigenous languages (in CD format) and delivery of presentations in English with simultaneous translation.

4.4 Partnerships

Key Findings: Partnerships between the federal, territorial and Indigenous governments, and others are recognized as integral to the success of NCSP. With the partnerships between the federal and territorial governments generally productive, those with Indigenous governments and partners have been strained and trust has been eroded.

Implementation of a partnership model for some remediation projects has resulted in marked improvement in relationships with some Indigenous groups in the last few years.

Extent Partnerships Contribute to the Achievement of NCSP Outcomes

Utility of Existing Partnerships

There is clear evidence that partnerships between federal, territorial and Indigenous governments, and others, are integral to the success of NCSP. While partnerships among federal and territorial parties have generally been productive, those with Indigenous governments and partners have been strained. There is evidence of improvement in these relationships for some remediation projects in recent years.

Breadmore & Lafferty (2015) concluded that the engagement processes used in the Discovery, Colomac and Great Slave Lake projects have led to effective long-term partnerships with communities:

"Through NCSP, positive relationships and partnerships have been forged with many Aboriginal governments and communities. Contaminants and Remediation Division's relationship with the Yellowknives Dene First Nation on the Discovery Mine Project continues today through long-term monitoring involvement and third-party activities at the site. The partnership formed between Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and the Tlicho in the early stages of the Colomac Project remain strong this day, as evident by a letter of support received from the Tlicho for the aquatic-terrestrial sampling permit requested by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada in 2013 and through data sharing under the Marian Lake Watershed Stewardship program. The Great Slave Lake Remediation Project has benefitted from these past relationships and partnerships and has strong project support within the Akaitcho Dene and Métis communities. It is anticipated that these relationships will strengthen as the project progresses"Footnote 12.

Internal interviewees stated that partnerships have been a critical element of reconciliation discussions, and have adjusted how NCSP manages projects.

A partnership model is increasingly being used for larger projects, such as FMRP and GMRP. Developing long-term partnerships has been a priority for the GMRP and it was suggested as a reason why CIRNAC has maintained a local senior presence. CIRNAC and Government of NWT are co-project proponents of the GMRP. Governed by a cooperation agreement and supported by a joint management structure, the partnership was felt to be very effective from working level through to senior management. Federally, Department of Fisheries and Oceans and Environment and Climate Change Canada are partners involved in the project's regulatory aspects. Indigenous governments, specifically the Yellowknife Dene First Nation and the North Slave Métis Alliance, are also important partners. The relationship with these groups has improved markedly in the last few years. They have been involved in developing the final closure and reclamation plan for water licensing (under consideration by the Mackenzie Valley Land and Water Board). Part of the development of the closure plan was extensive surface design, which involved a collaboration of First Nations, federal partners and the public. The City of Yellowknife and Alternatives North (a social advocacy group) also served as partners. This was also the experience with the FMRP environmental assessment process where input from partners occurred prior to submission to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board. These collaborative approaches are considered to lead to higher quality projects, as there is broad support from all stakeholders.

The relationship with Indigenous partners was described in mixed terms. Internal interviewees characterized relationships as being sometimes challenging, but professional and open with the aim to get the best results on both sides. External interviewees, however, were critical of the program's partnership efforts with Indigenous parties. External interviewees indicated that there were difficulties with: consultation and engagement; access to economic development opportunities; and, limited involvement in project decision-making.

Some of the same interviewees observed that with a mandate from the Prime Minister for nation-to-nation negotiations, it is expected that partnerships with Indigenous peoples will improve.

4.5 Consultation and Engagement

Key Findings: There is some evidence that NCSP has met its statutory obligations to consult with Indigenous parties. Although there was broad agreement that meaningful consultation and engagement have the potential to support reconciliation and socio-economic development, there was little evidence that this had occurred over the evaluation period. The widely supported GMRP surface design engagement process and the QRA engagement process are notable examples, which have yielded promising approaches.

Extent Consultation and Engagement has Produced Results

Design and Delivery of Consultation and Engagement

While there is some evidence that NCSP has met its statutory obligations to consult with Indigenous parties, there is limited evidence that meaningful consultation and engagement to support reconciliation and socio-economic development occurred over the evaluation period. The program has, however, actively sought to improve the quality of consultation and engagement and efforts have yielded promising approaches, such as the GMRP surface design, QRA and socio-economic development strategy engagement processes.

Definitional Issues

It was found that there was widespread inconsistency in the use of the terms "consultation" and "engagement", and terms describing stakeholder groups involved in contaminated sites projects amongst interviewees. These definitional challenges are important because they have shaped the expectations of all stakeholders involved in contaminated site remediation projects.

Among interviewees, some defined "consultation" as the legal duty to consult where there is a right or an asserted right, and "engagement" as a less formal process of ongoing two-way dialogue, from the time an environmental assessment decision is rendered, and working with a broader group of stakeholders with vested interest, rather than asserted right, in the project. Other interviewees held the opposite view.

It was further found the inconsistent use of terms describing groups involved in contaminated sites projects. For example, "partner" and "stakeholder" are regularly conflated, an important issue since the former conveys a level of ownership, including joint decision‑making and other associated expectations that the latter does not. Terms such as "rights holders," "intergovernmental participants," "signatories", and "parties" were viewed as acceptable.

The documentation review found similar definitional challenges. For example, the NCSP Management Policy and the more recent Major Projects Manual establish the requirements for consultation and engagement with Indigenous peoples and Northerners. The Corporate Procedures Manual notes that the requirement to consult is based on both the legal duty to consult as well as non-legal duties stemming from reconciliation and the promotion of Indigenous partnership and participation in projects. The non-legal duty "arises from a guiding principle of the CIRNAC Contaminated Sites Management Policy, which is to promote Indigenous and northern participation and partnership in the identification, assessment, decision‑making, and remediation/risk management processes related to contaminated sites."Whereas, the Major Project Standards and Guidance Manual distinguishes between consultation and engagement activities, in which consultation refers to various formal obligations, while engagement refers to meaningful and effective relationship‑building.

Indigenous interviewees were generally of the view that consultation has only been undertaken because legal requirements compelled the Crown to do so, and that the Crown followed the "letter of the law only, not respecting the spirit of reconciliation." Other external interviewees recommended that federal engagement processes occur from the project start, and be driven by reconciliation considerations and government-to-government relationships, rather than scientific and engineering needs. It was suggested that "social licence" be treated like a regulatory permit, a mandatory step prior to the start of a remediation project to obtain "a community's acceptance of an undertaking that they believe has the potential to have an effect on their well-being"Footnote 13.

Meaningful Consultation and Engagement

The documentation review found that the standards for consultation and engagement for major projects are established in the Major Project Standards and Guidance Manual. Major projects are required to develop and execute a consultation and engagement management plan, containing an Indigenous and stakeholder map, a consultation and engagement framework and process and "variations to Aboriginal and other stakeholder engagement activities across the project life cycle."Major projects are also required to employ a consultation and engagement manager "responsible for consulting with and engaging Aboriginal groups and other affected stakeholders to meet project planning, regulatory assessment (e.g., environment assessment) and ongoing project execution objectives."NCSP project documentation confirmed that consultation and engagement management plans have been developed, and consultation and engagement managers retained, where required.

External interviewees defined meaningful consultation and engagement as a process that begins with informed consent, combines Indigenous traditional knowledge and Western technical and scientific knowledge (building "a bridge between those two worlds and put it into these processes"), where the federal government actively listens to the input provided and clearly explains how this input will be used to make future decisions about site remediation. The 2018 FCSAP Evaluation noted that meaningful engagement contributes to the creation of social licence, buy-in and confidence among stakeholders, and, furthermore, establishes a greater imperative for government to follow through on promises.

The consultation and engagement processes were described by Indigenous interviewees as haphazard and inconsistent, with limited learning across remediation projects. These respondents expressed that decisions are still being made without their involvement and that NCSP did not recognize the value of broadly participatory processes where all parties have legitimate input into the development of options and objectives. Many internal interviewees identified similar shortcomings, acknowledging that while consultation and engagement had improved considerably over the evaluation period, "older thinking" still persisted in pockets. Several respondents stressed the need to build relationships based on trust with Indigenous parties. It was also suggested that the NCSP staff responsible for engagement be involved and embedded in the affected communities on a daily basis, to participate in community events and ensure NCSP clearly understands how to interact with communities.

An example of a meaningful engagement process offered by interviewees was the one supporting the plans for the remediation of the surface of the Giant Mine Site. Issues with the GMRP's attempt to obtain a "social licence to operate" through meaningful consultation and engagement triggered an environmental assessment under the Mackenzie Valley Resources Management Act. The approval of the environmental assessment in 2014 included 26 measures to be addressed before the water licence process, including improvements to the consultation and engagement process. This led to the widely respected surface design engagement process.

NCSP Capacity for Meaningful Consultation and Engagement

External interviewees were generally of the opinion that CIRNAC views remediation primarily as a technical exercise, and does not make enough effort to include affected people and communities. These interviewees also generally expressed concern that there was an absence of culturally sensitive interpersonal skills to meaningfully execute consultation and engagement.

External interviewees further suggested that remediation project teams be given a clear reconciliation and recognition mandate to lead remediation processes, with federal and contracted technical and scientific staff brought in to address technical matters only on an as-required basis. Others suggested retaining an independent outside firm to manage the consultations, as had occurred for the GMRP surface design and QRA processes.

The remoteness of affected communities amplifies costs of consultation and engagement in the North. With an engagement budget of $25,000 annually, the regional Great Slave Lake project team could only travel to the affected community once. In the case of the Port Radium remediation project, a four-hour charter flight is required to travel to Déline and another 1.5-hour charter flight to the mine site.

Capacity of Indigenous Stakeholders to Engage Meaningfully in Consultation and Engagement

Capacity issues directly impact the success of site remediation projects. Indigenous stakeholders have been overwhelmed with requests to participate in consultation and engagement processes flowing from a wide variety of federal, territorial and private sector initiatives. Challenges to meaningfully contribute is a product of limited financial and human resources.

Amongst all interviewees it is recognized that capacity issues among Indigenous stakeholders directly impact the success of site remediation projects. It was suggested that Indigenous stakeholders do not have the expertise required to be fully involved in the decisions related to remediation projects, which are very technical in nature. As a result, they are required to contract external expertise, which is viewed as contributing to delays in the remediation projects.

Federal funding is provided to Indigenous parties (and others) to participate on remediation working groups, and retain technical and engagement expertise. However, external interviewees generally viewed the support to be inadequate, and in some cases, external support simply could not be maintained.

4.6 Socio-economic Benefits

Key Findings: There has been some improvement in the accessibility of employment and business opportunities for Indigenous peoples and Northerners. However, communities have not been adequately consulted on their specific economic development needs.

The ability of Indigenous and northern communities and businesses to build the required capacity to be ready as opportunities arise has been negatively impacted by the lengthy procurement lead time, contract uncertainty and limited financing options.

Bonding and insurance have been unnecessarily onerous, and federal procurement policies, procedures and processes inflexible. Penalties for firms failing to meet Indigenous employment and contracting commitments have been too small to be an effective deterrent.

Extent NCSP has Contributed to Socio-economic Benefits

Contribution to the Socio-economic Benefits of Remediation

There is evidence that Indigenous and northern communities are benefitting from the socio‑economic benefits of contaminated site remediation, but despite some recent improvements, there is room for improvement.

Accessibility of the Socio-economic Benefits of Remediation

Indigenous and northern communities experience many barriers to accessing socio-economic benefits of contaminated site remediation, including uneven distribution of opportunities, challenging procurement processes, and lack of policy coverage to specifically target northern firms and job seekers.

Training, employment and contracting were identified by most interviewees as the primary socio‑economic benefits flowing from contaminated site remediation projects to Indigenous and northern communities. A recent study noted that training and capacity building was generally built into NCSP projects either through contribution agreements or through mandatory or point-rated procurement criteria, such as environmental sampling, environmental monitoring, water treatment and heavy equipment.Footnote 14

It was observed that "as long as there is mining, there will be remediation needs", and that, by building and maintaining a population that is skilled and trained, mining firms will have access to and use much more local content, and thus money will flow into local communities and remain in the North. It was further suggested that the long duration and the expected potential revenues associated with remediation offer the perfect conditions to build a viable and sophisticated Indigenous and northern supplier base that could execute at scale in the North and elsewhere.