Evaluation of the Contaminated Sites On-Reserve (South of the 60th Parallel) Program

Final Report

January 2016

Project Number: 1570-7/14089

PDF Version (782 KB, 82 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings – Design and Delivery

- 5. Evaluation Findings – Performance (Effectiveness / Success)

- 6. Evaluation Findings – Efficiency and Economy

- 7. Other Findings/Observations

- 8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Stages of Assessing and Remediating a Contaminated Site

- Appendix B - National Classification System for Contaminated Sites

- Appendix C - Breakdown of Environmental Liabilities by Custodian Department

- Appendix D – Logic Model

- Appendix E - Lands and Economic Development Expenditures and Liability, 2005-2015

- Appendix F - Literature Review Summary and Sources

- Appendix G - Document Review References

- Appendix H - INAC Contaminated Sites

List of Acronyms

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

|---|---|

| CSOR |

Contaminated Sites On-Reserve (Program) |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| FCSAP |

Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan |

| IEMS |

Integrated Environmental Management System |

| PWGSC |

Public Works and Government Services Canada |

Executive Summary

Introduction

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada’s (INAC) South of 60º Contaminated Sites On-Reserve (CSOR) Program (herein referred to as CSOR) provides assistance to First Nations by supporting the assessment and remediation of contaminated sites on-reserve lands and on any other lands under the Department’s custodial responsibility.

The overall purpose of this evaluation is to provide reliable evidence that can be used to support policy and program improvement related to INAC's environmental management responsibilities. The evaluation provides evidence-based conclusions and recommendations about the relevance and performance of the CSOR as per the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Evaluation, and also identifies best practices and lessons learned that might be applied to improve similar future programming.

The evaluation covers the period from 2009-10 to 2013-14, during which time $220.1M was spent on the program.

Methodology

Evaluation findings are based on information gathered from multiple lines of evidence, including:

- Document review;

- Database review;

- Literature review;

- Interviews with INAC National Headquarters and regional staff;

- Interviews with First Nations representatives;

- Site visits to First Nation communities; and

- Focus groups that included regional and Health Canada staff.

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

The evidence demonstrates a continued need for the CSOR, given the number of contaminated sites and significant environmental site assessment and remediation work yet to be addressed (e.g., assessing and classifying suspected on-reserve contaminated sites). Such work will contribute to a decrease in priority sites and a reduction in risk and liability.Footnote 1 The need for the program will continue as new sites emerge. While the Federal Contaminated Sites Program (FCSAP), as a key source of funding supports the CSOR, the CSOR is well aligned with federal priorities (e.g., the promotion of a cleaner environment, and economic development). Alignment is also demonstrated by the additional Canada Economic Action Plan stimulus funding given to FCSAP, which was to enable expedited work on both the assessment and the remediation of federal contaminated sites. The expected result is to improve the environment while encouraging economic growth. All of these complement other INAC activities, such as community rejuvenation and the broader environmental and economic strategies of the federal government. Finally, the CSOR is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities, which includes legislative obligations related to environmental stewardship. It is also consistent with INAC responsibilities and community priorities such as reducing or eliminating contaminated sites and environmental hazards, as well as contributing to the safety of on-reserve communities.

Design and Delivery

The CSOR's prevention strategies

There is a need to increase and strengthen the CSOR's prevention strategies in order to reduce or eliminate risks to human health and the environment, and reduce legal and financial liabilities associated with contaminated sites. INAC has undertaken work on a compliance plan to assist First Nations in meeting the 2008 Environment Canada Storage Tank Regulations, or help them with training for emergency fuel response and release, and the development of emergency and waste management plans. Yet, funding available for site clean-up is limited and moreover, very little if any remains for regions to offer effective contamination prevention or minor contamination do-it-yourself clean-up programs for reserves interested in preventative options.

Integrated Environmental Management System (IEMS)

The IEMS database facilitates the input of contaminated sites information to the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, which is a requirement of the Treasury Board Policy on the Management of Real Property. This database, together with site-specific Detailed Work Plans and quarterly site reports, informs both planning and reporting processes. However, IEMS users considered it to be a challenging system. For example, the IEMS dataset is incomplete and has a significant amount of inconsistent data or data duplication due to weak record keeping, reporting and data management. If the program is unable to adequately capture information, the quality of reporting suffers and where a system is not in place to easily capture the information, efficiency is lost through workarounds.

Information gathered as part of the evaluation suggests that challenges such as data duplication occur frequently. Given record duplication, the program uses workarounds to address data issues. Workarounds exist either because a system is too hard to use or it does not provide the function as required. Remedying the data in the IEMS database will keep its contents current, ensuring that it performs its vital function of keeping the Department abreast of the environmental situation across on-reserve communities.

Performance – Effectiveness

The CSOR is achieving its expected result that priority sites are remediated and risk managed and/or monitored. However, questions remain as to whether the program will be able to achieve full remediation, including closure of all contaminated sites. While the CSOR is enabling the reduction of liability, the total remediation liability for the CSOR is still prevalent due to the discovery and addition of new contaminated sites, which impact program-level progress on total liability reduction. There is also evidence to indicate that the secondary impacts of the program in the areas of employment and training are being achieved.

On the other hand, there is some evidence to indicate that secondary impacts of the program in the areas of employment and training are being achieved.

The CSOR Program is addressing the highest priority areas

The CSOR is achieving its key priorities of reducing the number of contaminated sites (Class 1 sites)Footnote 2, but restricted funding makes it difficult and limits attention on lower priority (Class 2) sites. Nonetheless, significant progress has been made in achieving priorities. First Nation evaluation participants, while mentioning their own community infrastructure priorities, acknowledged the importance of dealing with these priority areas (i.e., sites that are high risk and require action to address existing concerns for public health and safety).

Performance – Efficiency and Economy

Evaluation evidence indicates that not all risks and financial liabilities associated with contaminated sites will be addressed given challenges, such as budgetary restraints. The constant discovery of new sites suggests a continuous demand for funding. Aside from FCSAP funds, the CSOR faces challenges with respect to leveraging internal INAC funds to address contaminated sites. This is compounded by the uncertainty surrounding whether the CSOR will obtain FCSAP funding beyond its expected end in 2020.

Despite these difficulties, as well as the requirement to demonstrate that the CSOR is spending its (i.e. public funds) in an efficient and economical way, and that it is achieving a positive impact relative to its capacity, the evaluation found that the CSOR has performed well in terms of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress towards its expected outcomes.

Some Key Challenges to Performance

The Polluter Pay Policy/Principle on-reserve

The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, which is applicable on reserve embodies the principle that users and producers of pollutants and wastes should be held responsible for their actions. Similar, for example, to the federal Fisheries Act or the Species at Risk Act, Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, it is enforced on-reserve by the appropriate federal authorities responsible for these acts. In practice, however, enforcement of this principle on-reserve is complicated as it is accompanied by provincial compliance promotion elements (e.g., standards, certification, licensing, inspection), which are lacking on-reserve. Hence the evaluation found that the enforcement of the polluter pay principle on-reserve was a challenge, given the complex jurisdictional and legal context within which First Nations must operate.

A novel approach or solution to this gap can be found under the First Nations Land Management Act, where environmental protection standards are required. These must either meet or exceed provincial standards where there is a potential for pollution to occur. Moreover, in British Columbia, some treaties (e.g., the Maa Nulth Final Agreement) provide that provincial law will apply on First Nation lands.

Thus, the regulatory issue and the need for enforcement have led to challenges in ensuring environmental protection on-reserve. The polluter pays principle is meant to be one of the levers through which funding for remediation can be received, especially in cases where a polluter of a contaminated site is known.

Legislative GapFootnote 3

As the evaluation has found, there are some risks that need to be addressed, one of them being the lack of control, which is also related to Third Party risk. For example, by allowing activities which continue to cause small scale pollution on-reserve, there is a risk that INAC may be held responsible for contamination as a result of activities which INAC does not perform and/or manage. Another key observation is that if the particular on-reserve community does not show diligence in prevention and monitoring, INAC may be liable for the contamination that may result. Thus, with INAC as a whole there are difficulties in monitoring all activities on-reserve, yet INAC could be responsible, or for health and safety reasons assume responsibility, for its remediation.

In fiscal 2015-16, Lands and Economic Development created a User’s Guide on Determining INAC and Third Party Contaminated Site Responsibility. This document is intended to address the challenges associated with the polluter pay principle by detailing information related to each step to be taken to identify a polluter. The document covers orphaned or abandoned sites, polluters who do or do not accept the responsibility for pollution and other topics. Building on this guide, the CSOR may benefit from a strengthened liability regime.

Impact, both intended and unintended

There is general agreement among interviewees that the CSOR has had a significant positive impact in several areas, including a beneficial impact on First Nations overall. High priority (Class 1) sites are being remediated, pollution sources are being documented, and to the extent possible, awareness of the need for appropriate fuel handling and tank management procedures is being raised within on-reserve First Nation communities. It is expected that an increase in the community’s awareness will contribute to the program’s prevention efforts.

Recommendations

It is recommended that the CSOR Program:

- Review the integrity of the IEMS data to ensure that they are accurate, reliable and usable; and

- Coordinate its activities with other complementary programs within the Department in order to improve First Nation communities' awareness and response to fuel and waste management issues.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Management of Contaminated Sites On-Reserve, South of the 60th Parallel

Project #: 1570-7/13071

The Contaminated Sites On-Reserve (CSOR) Program, Lands and Environmental Management Branch and Lands and Economic Development Sector agree with the recommendations produced in this evaluation. There is recognition at all levels of the importance of addressing contaminated sites related to First Nations, for a multitude of reasons, and in making the Contaminates Sites On Reserve Program as effective and successful as possible.

The CSOR program has been very successful in its primary mission to remediate contaminated sites, protect human health and safety and improve environmental integrity on-reserve. These successes were achieved despite having limited financial resources and limited personnel. Sound financial and program management have allowed the CSOR program to be successful in making the case for and securing additional funding for contaminated sites both from within the Department and from custodians of other government departments who are participants in the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan.

The evaluation recommendations are in line with work already underway to improve the CSOR program and findings will inform future policy and process improvements.

The CSOR program has made significant recent improvements to the Integrated Environmental Management System (IEMS) data and strives to have the best system possible given available resources. Changes are continually being made to improve the data currently in the system and to respond to any new reporting requirements from central agencies.

The CSOR program coordinates its activities with many stakeholders. It collaborates fully within INAC with the Northern Contaminated Sites Program, Regional Operations and other preventative programs in the Department and will strive to continually improve horizontal collaboration.

The CSOR program will continue to be effectively managed, receive continued departmental support and strive to achieve its objectives. These include protecting human health and safety and improving environmental integrity on-reserve; developing a more accurate picture of contaminated sites on-reserve, reducing total contaminated sites liability for known sites; and, making land available to First Nations for community or economic development.

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Review the integrity of the IEMS data to ensure that they are accurate, reliable and usable; | We do concur. | Susan Waters Director General, Land and Environmental Management Branch | Start Date: February 2016 |

|

Completion: There will be ongoing continual improvement for IEMS system and data. Completed |

||

| 2. Coordinate its activities with other complimentary programs within the department in order to improve First Nation communities' awareness and response to fuel and waste management issues. | We do concur. | Susan Waters Director General, Land and Environmental Management Branch | Start Date February 2016 |

|

Completion: March 2017 Completed |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original Signed by:

Michel J. Burrowes

Senior Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original Signed by:

Sheilagh Murphy

Assistant Deputy Minister, Lands and Economic Development

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This report presents the results of an evaluation of the ContaminatedSites South of 60º (CSOR) Program. The overall purpose of the evaluation was to provide evidence able to support policy and program improvement related to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) environmental management responsibilities. As required by the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Evaluation, the evaluation provides evidence-based conclusions and recommendations with regard to the relevance and performance of the program and identifies best practices and lessons learned that could improve similar future programming.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

The CSOR is an environmental management program delivered by INAC and that funds First Nations to undertake environmental site assessment and remediation or to risk manage contaminated sites on-reserve and other lands under INAC (Lands and Economic Development) jurisdiction. These activities are supported to reduce or eliminate risks to human health and the environment, and to reduce legal and financial liabilities associated with contaminated sites. The CSOR is administered in accordance with INAC's Contaminated Sites Management Policy (2002) and the Federal Approach to Contaminated Sites developed by the interdepartmental Contaminated Sites Management Working GroupFootnote 4.

Implementation of the CSOR Program by INAC is supported by Environment Canada's Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan Program (FCSAP) which provides funding for the CSOR on a cost-share basis. The FCSAP provides the majority of funding while INAC's Regional Operations'Footnote 5 Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program provides the balance. The Department's Lands and Economic Development Sector coordinates and flows funding to First Nations, liaises with the FCSAP Secretariat and Treasury Board Secretariat, and works with First Nations to develop and secure contracts for work to be undertaken on-reserve.

1.2.2 Overview of Contaminated Sites and Site Remediation Policy

Contaminated Sites

A contaminated site is defined by the Treasury Board as "a site at which substances occur at concentrations that: (1) are above background levels and pose, or are likely to pose, an immediate or long-term hazard to human health or the environment; or (2) exceed the levels specified in policies and regulations". A site can be redefined as no longer contaminated once remediation and any necessary long-term monitoring activities have been completed or because it was determined through an established assessment process that no action is required.

As identified under the National Classification System for Contaminated Sites, a contaminated site could also be Class 1 (i.e. sites where action is required to address existing concerns for public health and safety) or Class 2 (i.e. sites that have a high potential for adverse off-site impacts, although threats to human health and the environment are not imminent).

In 1992, INAC initiated the Environmental Issues Inventory and Remediation Plan. The Plan represented a multi-phase effort to identify and document environmental problems that pose dangers to the environment and to the health and safety of First Nations communities as well as to assist the Department in meeting its legal obligations under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, the Fisheries Act and other applicable legislation. The inventory represented the first step taken by the Department to manage contaminated sites on-reserve land and included all environmental issues that dealt with subsurface contamination and those where INAC had spent funds or intended to spend funds on environmental site assessments or remediation/risk management.

Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan (FCSAP)

In October 2002, the Report of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Footnote 6 criticized the federal government's lack of progress in the management of contaminated sites across Canada. In response, the FCSAP was developed as the successor program to the two-year, $175 million Federal Contaminated Sites Accelerated Action Plan created in 2003. The FCSAP is a cost-shared program for eligible legacy contaminated sites that were contaminated before April 1, 1998.Footnote 7

In 2003, the Environmental Issues Inventory and Remediation Plan initiative was moved into the Contaminated Sites Management Program. This broadened the focus from assessments under the Environmental Issues Inventory and Remediation Plan to include remediation and risk management. The following year, the FCSAP was announced and had a $3.5 billion budget over 10 years to remediate and manage high-risk federal contaminated sites. In 2005, the duration of the FCSAP was extended to 15 years with the same level of funding.

The FCSAP has two key goals: (1) to reduce the risks to human health and the environment caused by contaminated sites; and (2) to reduce the financial liability for known federal contaminated sites by 2020. The FCSAP pays a percentage of costs (85 percent for remediation/risk management and 80 percent for assessment) with INAC covering the remainder (15 percent for remediation/risk management and 20 percent for assessment).

The FCSAP has 16 custodians (federal departments and consolidated Crown corporations or agencies), responsible for federal contaminated sites and which develop proposals and lead remediation efforts for sites. INAC is one of the custodians that have entered into funding agreements with FCSAPFootnote 8. In order for a custodian to receive FCSAP funding, contaminated sites must:

- meet the Treasury Board definition of a contaminated site;

- have been contaminated due to activities that occurred prior to April 1, 1998;

- be on lands owned or leased by the federal government;

- be either Class 1 or Class 2;Footnote 9 and

- represent a financial liability-associated site as reported in the Federal Contaminated Sites InventoryFootnote 10.

FCSAP has evolved and continues to evolve through three five-year phases:

- Phase I 2005–2011;

- Phase II 2011–2016; and

- Phase III 2016–2020.

Phase I resulted in custodians conducting remediation activities at 1,400 sites and completing remediation at 650. In addition, Phase I resulted in assessment activities conducted on over 9,400 sites with 6,400 completedFootnote 11. Under Phase II (approved in June, 2011), only Class 2 sites with remediation expenditures prior to April 1, 2011, are eligible for remediation funding and approximately $1 billion be invested over the first three years for Phase II. In Phase III of FCSAP, it is expected that federal custodians will continue to focus their assessment activities on identifying the highest priority sites. In addition, remediation activities will target the highest priority sites in order to reduce liability over the Phase III period.

Overview of the Contaminated Sites On Reserve Program

The Contaminated Sites On-Reserve Program is guided by a number of key departmental and federal environmental policies such as:

- Contaminated Sites Management PolicyFootnote 12 (2002): intended to provide guidance for the management of contaminated sites located on-reserve lands, on federal lands north of the 60th parallel, and on any other lands under INAC's custodial responsibility;

- Contaminated Sites Management Directive: which aims to provide an integrated, consistent, cost-effective and coherent approach for all sectors and regions in implementing the Contaminated Sites Management Program;

- INAC's Environment Policy (2003): provides direction and guidance to INAC sectors and regions in meeting federal environmental obligations;

- INAC Environmental Management Directive (2005): provides direction to INAC sectors and regions in implementing the INAC Environment Policy and supporting departmental compliance with all applicable federal environmental legislation, regulations, policies and guidelines; and

- INAC Policy on Accounting for Environmental Liabilities (2013): sets out the roles and responsibilities in the accounting and reporting of environmental liabilities.

As of March 2012, almost 22,000 federal contaminated sites had been identified, including those on-reserveFootnote 13. By March 2013, the CSOR managed 2,392 active contaminated sites on reserves south of latitude 60˚N; 293 of those sites are Class 1 — high risk to human health and safety. In 2014, 67 percent of contaminated sites south of 60º were related to fuel storage and handling, 20 percent were related to solid waste/landfills, and 13 percent were related to other contaminatesFootnote 14. The leading causes of contamination include leaking fuel storage tanks, inadequately managed waste sites, and orphan industrial sites. On March 31, 2013, the reported liability of these sites was estimated at $246.6 million.

1.2.3 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The CSOR is expected to contribute to the expected result of community development by supporting the assessment and remediation of contaminated sites on-reserve lands and on any other lands under INAC's custodial responsibility. It supports the assessment and remediation of known contamination from the National Classification System for Contaminated Sites Class 1 and Class 2, for which a liability to the Crown has been established and documented. The expected outcomes for the Contaminated Sites On-Reserve are:

Immediate Outcomes

- Priority sites are remediated, risk managed and/or monitored.

Intermediate Outcomes

- Federal liabilities related to the existence of contaminated sites are reduced; and

- Decreased risk to public health and safety.

Final Outcomes

This sub-program is one of four, which supports the Community Development (3.2) program with the expected results of:

- Enhanced conditions for First Nation and Inuit communities to pursue greater independence / self-sufficiency and sustainable economic development; and

- First Nation land is available for economic development.

The Community Development program supports the Land and Economy Strategic Outcome:

- Full participation of First Nations, Métis, Non-Status Indians and Inuit individuals and communities in the economy.

1.2.4 What classifies as an on-reserve contaminated site

Contaminated sites on-reserve land south of 60º are mostly related to abandoned dump sites and fuel spillsFootnote 15. These are sites that pose, or are likely to pose, an immediate or long-term hazard to human health and/or the environment and are often a legacy of past practices. If not managed properly, these sites, particularly those identified as having a higher risk to human health and safety, may have a significant impact on the ability for First Nations communities to capitalize on land-based economic development opportunities.

1.2.5 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

INAC is the federal department responsible for the delivery of Contaminated Sites On-Reserve.

INAC Headquarters

The Lands and Economic Development and Regional Operations Assistant Deputy Ministers have overall responsibility for ensuring the consistent implementation and application of the Policy. Responsibilities include: coordinating regional and national Contaminated Sites Management Plans; and working with regions to implement them.

The Contaminated Sites On-Reserve Program is administered at INAC Headquarters by the Environment Directorate of the Lands and Environmental Management Branch. The Director is responsible for the financial administration of the program and national policy development as well as the authorized official for the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory CertificationFootnote 16. Additional responsibilities of the Environment Directorate include:

- Preparing, coordinating and reviewing responses to audits and evaluations (INAC and Office of the Auditor General);

- Overseeing data management of the Integrated Environmental Management System (includes development, enhancements, maintenance, guidance and advice);

- Providing advice and guidance to regional officers on industry standards and methodologies;

- Preparing Future-Oriented Financial Statements and year-end estimated environmental liabilities in consultation with the regions as required and the preparation of the Public Accounts Plate TA5aFootnote 17; and

- Developing and implementing the national work plan for priority sites with regional input and approval.

The Environment Directorate also liaises with the Regional Operations Sector at Headquarters regarding the Department's planned cost-shared funding required by the FCSAP program.

INAC Regions

Regional directors general are responsible for implementing Regional Contaminated Sites Management Plans and ensuring they are supported by, and well integrated with, other regional programs and activities. Directors general oversee the development and approval of annual project work plans and long term regional strategic plans for the program. Ultimately, they are accountable for the FCSAP and the departmental resources the region manages in support of the program. Regional responsibilities include:

- Liaising with and providing functional direction and advice to First Nation communities in relation to contaminated sites;

- Funding Management - preparing documentation for funding amendments, proposals and reporting management;

- Site Inspections;

- Completing modified Phase I Environmental Site Assessments;

- Maintaining the Integrated Environmental Management System (IEMS) database, which reports to the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory;

- Program reporting for the FCSAP and Contaminated Sites (On-Reserve);

- Liaising with the FCSAP Expert Support Departments; and

- Preparing site closures for every completed remediation project.

Eligible First Nations

"Eligible First Nations." These include: First Nations living on lands of known and suspected Class 1 or 2 contaminated sites; Band/Settlements and Communities; District Councils/Chief Councils; Tribal Councils; First Nation Organizations, Associations and Institutions.

INAC and First Nations manage and implement contaminated site projects in partnership, thereby allowing for project ownership and potential economic benefit for the communities concerned. Sound environmental management and protection ensures lands are available for the pursuit of opportunities in business development, residential expansion and cultural/traditional activities.

First Nations report to INAC through Data Collection Instrument reporting requirements on a quarterly basis (or at six month intervals) and at the end of the fiscal year. They also provide consultant or other reports pursuant to Funding Agreements under the approved scope of work.

FCSAP Secretariat/Other Federal Departments

The FCSAP Secretariat, based in Environment Canada, is responsible for the administration of the FCSAP, which is a cost-shared program that assists federal custodian departments, agencies and consolidated Crown corporations to address contaminated sites for which they are responsible. It is one source of funding for the CSOR and its function includes leading and coordinating its delivery, coordinating the review of proposals and managing the project selection process. The Secretariat tracks funding requests and project expenditures and also develops funding allocation proposals for approval by the Federal Contaminated Sites Steering Committee.The Secretariat also develops the procedures required to ensure interdepartmental consistency in program implementation, while providing clerical and administrative services to the Federal Contaminated Sites Steering Committee and the Contaminated Sites Management Working Group. Reporting on the effectiveness of the program is a key role of the FCSAP Secretariat.

Treasury Board Secretariat

The FCSAP Secretariat co-administers the program with the Treasury Board Secretariat, whose Real Property and Materiel Policy Division is responsible for ensuring consistency with Treasury Board policies on the management of federal real property, including federal contaminated sites. The division also administers and maintains the Federal Contaminated Sites InventoryFootnote 18, assisting the FCSAP Secretariat with the monitoring of and reporting on government-wide progress in addressing federal contaminated sites funded under the FCSAP.

Through FCSAP funding, three federal departments (Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Health Canada) partner or collaborate with INAC to manage federal contaminated sites. They provide expert support to INAC and ensure compliance with legislation under their jurisdiction that affects Crown lands. They also support the FCSAP Secretariat with the development and promotion of best practices. Custodians are thereby able to adopt a consistent national approach to human health and ecological risk assessment. More specifically, the roles and responsibilities of the three departments are as follows:

Environment Canada

The Department houses the FCSAP Secretariat, administers FCSAP and provides program guidance and leadership to custodians, including expert support with regard to contaminated sites, ecological risks and environmental matters. It also assesses and remediates its own sitesFootnote 19 and administers and coordinates the FCSAP program across the federal government.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Fisheries and Oceans Canada deals with aquatic sites to ensure a sustainable aquatic ecosystem and where applicable, provides expert support to custodians regarding early planning, ecological risk assessments, remediation, risk management and long-term monitoring of FCSAP sitesFootnote 20.

Health Canada

Health Canada's responsibilities include: "Reviewing human health risk assessment and related reports from contractors, custodial departments and provincial regulatory authorities; collaborating with Health Canada's Environmental Health Assessment Services, an authority on integration of health issues in environmental assessments conducted under theCanadian Environmental Assessment Act; and providing custodial departments with expert advice, guidance, training and tools on best practices and innovative methods for human health risk assessment and incorporating stakeholders into contaminated site management"Footnote 21.

FCSAP - Other Departments

Public Works and Government Services Canada and Industry Canada

Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC) provides support and advice to custodians on project management and innovative technologies through the development of project management tools, the diffusion of information on technologies as well as liaison with industry. Others with interests in the FCSAP support the program within their existing mandates, for example, Industry Canada, like PWGSC, provides support to custodians by facilitating familiarization and collaboration between custodians and remediation technology vendors offering advanced innovative technologies.

Provinces - legislation

Provincial governments are stakeholders because "they are responsible for preventing pollution and contamination within their jurisdictions and on federal Crown lands, which includes reserves and lands adjacent to reserve lands"Footnote 22. For the same reason, municipalities are also program stakeholders.

The provinces have a number of pieces of legislation that address contaminated sites in their respective jurisdictions (not including reserve lands, which are the responsibility of the federal government). Only Ontario, however, offers a financial incentive in the form of a tax incentive for the remediation of brownfield sites.Footnote 23 All other provinces put the financial burden on the polluter. Since reserves are federal lands, the role of provinces as key stakeholders with respect to contaminated sites on-reserve differs from others and, for example, provincial legislation that affects land does not apply on-reserve.

1.2.6 Program Resources

Table 1 shows the operating expenditures and contributions of the CSOR from 2009-10 to 2013-14.

| 2009–10 | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary | $1,269,453 | $1,685,593 | $1,354,138 | $1,399,209 | $1,197,904 | $7,783,397 |

| Operations and Maintenance | $543,933 | $2,088,008 | $385,246 | $794,265 | $1,533,271 | $5,753,494 |

| Statutor – EBP* | $223,220 | $294,202 | $210,189 | $226,841 | $192,970 | $1,284,907 |

| Contributions | $46,287,894 | $56,864,798 | $16,521,848 | $29,014,199 | $30,321,868 | $205,303,119 |

| Total | $48,324,500 | $60,932,600 | $18,471,421 | $31,434,515 | $33,246,013 | $220,124,917 |

*EBP stands for Employee Benefit Plans. |

||||||

Note: While operating expenditures have been generally consistent between 2009–10 and 2013–14, contribution levels have varied year to year, with a large decrease in 2011–12.

Levels vary from year to year since they depend upon the program's ability to source funds within INAC and other departments, mainly FCSAP, Capital Facilities and Maintenance, Northern Contaminated Sites, and First Nations Land Management.

A contaminated site project is eligible for $10 million in funding annually. Where a project goes beyond this amount, approval (as in the case of a Capital project) is required from INAC's national headquarters. Projects are funded through contribution agreements between individual First Nations and INAC. The allocation and amount of funding are based upon an environmental assessment of the work required and depend upon various factors, including site classification score, human and/or ecological health receptors, type of land use (e.g., residential), the amount of available funds, legal obligations, economic development opportunities and cost-sharing opportunities. Depending on the region, payments are made monthly based on the recipient's cash flow forecastFootnote 24. For example, in Manitoba, payments are made on the progress of the particular project and also on actual work done.

Table 2 shows the 2013–14 planned and actual program budget.

| $/Full-Time Equivalents | |

|---|---|

| Budgetary Financial Resources ($) | |

| Planned spending | $17,909,251 |

| Actual spending | $33,246,013 |

| Difference (actual minus planned) | $15,336,762 |

| Human resources (Full-Time Equivalents) | |

|---|---|

| Planned | 16.1 |

| Actual | 11.5 |

| Difference (actual minus planned) | (4.6) |

Source: INAC, 2014c) |

|

Note: The table is consistent with Table 1 and shows that the program spent over $15 million more than expected in 2013–14 due to the sub-program's ability to access additional resources from FCSAP and other sourcesFootnote 25. Table 2 also shows that the program was able to operate in 2013–14 with about 4.6 less full-time equivalents than originally expected.

Funding for CSOR on-reserve comes from various sources: externally, from FCSAP and other federal departments (i.e. other FCSAP custodians); internally (i.e. INAC), from Lands and Economic Development, Regional Operations, the Northern Affairs Organization, and INAC Financial Management Committee requests.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

In 2008, INAC evaluated the Department's Contaminated Sites Management Policy and Programming (CSOR), including the North of 60º and South of 60º programs. In June 2012, an internal audit of the CSOR was completed, together with follow-up reports on the program's response to the audit recommendations. Also in 2012, the Office of the Auditor General included an examination of the FCSAP as part of its audit activities. In 2014, Environment Canada completed an evaluation of the FCSAP, which funds the majority (i.e. the assessment and remediation) of INAC-related contaminated sites program.

The current evaluation, the first of the CSOR, also looks at contaminated sites on-reserve as reserves fall within INAC's responsibilities. This evaluation has relied upon the extensive research and analysis undertaken in the course of the above audits and evaluations, to build on the existing literature while easing the reporting burden on the program. Due diligence was exercised in gathering up-to-date information while avoiding duplicating information gathered during the earlier audits and evaluations.

The evaluation examined CSOR program activities between 2009-10 and 2013-14. Terms of Reference were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 20, 2014. Field work was conducted between June and October 2015.

2.2 Evaluation Methodology

The evaluation's findings, conclusions and recommendations are based on information gathered from these lines of evidence: literature, document and database reviews; site visits with focus group sessions; and key informant interviews.

Literature Review

The purpose of the literature review was to acquire a greater understanding of contaminated sites and approaches to determining, classifying and dealing with contaminated sites on-reserve land across various Canadian jurisdictions; and, examine the impact of contaminated sites on-reserve south of the 60th parallel. The literature was selected and reviewed on the basis of its relevance to the evaluation and it included peer-reviewed journal articles, magazine and newspaper articles. A three-part annex of supplementary information was reviewed together with four topical papers: The "First Nation Involvement in Remediation Efforts"; "Contamination Due to Insufficient Resources"; "Dangers to Food, Water, and Air Both on and off Reserve Lands"; and "Risk-Ranking," (which compares national and provincial classification methods for contaminated sites and the follow-up actions to be taken regarding remediation). The findings helped to inform the choice of which on-reserve sites to visit, the questions posed in key informant interviews, as well as the data and document review.

Document Review

A document review of the program was conducted, structured around identified evaluation issues and questions (see Appendix G, Documents Sources), that included the review of approximately 60 documents including, but not limited to:

- Reports produced by the Office of the Auditor General;

- INAC audits, evaluations, and special studies;

- FCSAP-related governmental documentation sites;

- INAC website and other related web pages;

- INAC Departmental Performance Reports and Reports on Plans and Priorities;

- Governmental Policy documents; and

- Provincial legislation and other related contaminated sites documents.

The document review helped to inform the evaluators' understanding of the governance structure of the CSOR, the broader FCSAP initiative and the roles and responsibilities of various parties involved in the program's delivery.

Database Review

The database review included the IEMS database (together with data on liability provided directly by the program), and a review of the publicly available Federal Contaminated Sites InventoryFootnote 26, housed by the Treasury Board Secretariat. The database review was undertaken for several reasons, including viewing the CSOR Program's records of site investigations and cleanups, verifying the robust information collection and reporting nature of the IEMS, accessing information on reported sites, obtaining information on classified sites with confirmed (known) contamination, gathering information on where instances of site contamination mainly occur (e.g. on-reserve areas affected by site contamination issues that are the direct result of past practices such as fuel storage and associated spills and leaks), etc.

As a way of examining the program's relative progress across provinces in assessing and remediating contaminated sites, the database review included, among others, an analysis of level of classification of site by region. The IEMS database also yielded financial information that informed the effectiveness of the program's use of funding.

Site Visits

There were four site visits, which were primarily visual inspection of the sites and interviews with people involved in or linked to the sites (e.g., community representatives and project managers). Sites broadly illustrative of the CSOR were chosen among Manitoba and Ontario First Nation communities assessed as having high priority contaminated sites or were representative of various stages of assessment and remediation. The site visits also included walk-throughs, to identify areas of potential environmental concern to on-reserve communities. These were used to verify the information gathered during the literature review. Planned visits to communities in British Columbia could not be undertaken as the communities were unavailable. It was hoped that the opportunity provided by the evaluation would result in input from British Columbia reserve communities.

Key Informant Interviews/Focus Group

To increase understanding of the CSOR program and its delivery, 17 interviews were conducted in person or by telephone with individuals with direct experience and knowledge of the management of contaminated sites on-reserve. Those interviewed included INAC Headquarters (four CSOR) and regional staff. Interviews during site visits included First Nation community members and contractors. Focus group sessions were held (included eight regional and Health Canada staff).

2.2.1 Strengths and Limitations

The evaluation did not benefit from the presence of a working group since the program was short-staffed, managing competing priorities.

Barriers to effective implementation of the evaluation included: the absence of subject-matter experts with whom evaluators could have worked to achieve the evaluation's goals and objectives; staff turnover and lack of key member input into the evaluation plan; dependence on a variety of individuals during both the planning phase and the course of the evaluation. Nonetheless, the evaluation did benefit from recent audits and evaluations and, with FCSAP Phase III beginning in 2016, from current work on Phase III, including supplementary information from the research being undertaken for Phase III purposes.

Limitations

Fieldwork Delays

The evaluation methodology necessitated undertaking site visits in tandem with already scheduled and ongoing activities of numerous partners in order to capture information that may not be available at other times. The challenges associated with the scheduling of these visits (e.g., partner coordination and travel, weather, accessibility, community readiness, etc.), affected the fieldwork timing, resulting either in delays in data collection and analysis or cancellation of key site visits. As a consequence, the original number of site visits was reduced from seven to four.

Mitigation: Despite the elimination of the three site visits from the study design, the similar nature of the projects, coupled with documents that were reviewed provided information needed. Further, the evaluation design and implementation were appropriate for the objectives of the study, a key strength of the evaluation design being that it took into consideration the broader program theory, which was supported by contaminated site conceptual/analytical framework.

Data Analysis Limitations (Integrated Environmental Management System)

The content of the IEMS database changed daily, resulting in a different number of projects in the database depending on the date the data was provided. For example, a data set provided on April 24 (dates of steps completed - see "8. Appendix A. Stages of Assessing and Remediating a Contaminated Site") included 3,446 unique projects, while a data set provided on April 29 (current step and classification of projects) included 3,440 unique projects leading to inconsistent data sets.

While this was a live database hence the inconsistency, the complication is attributed to the fact that the dataset was found to include data on sites being managed by other federal departments, that fell under provincial/territorial responsibility or that were a third party responsibility. Thus, all these had to be excluded from the CSOR data analysis. Given the need to clean the data, some frequencies had to be recalculated multiple times using different data extractions provided by the program.

For example, in determining the amount of time taken to complete certain tasks for a project (i.e., steps), a number of the values came back as a negative number of days. The explanation given was that this may be because a project that had a long period of inactivity may have had to go back and repeat steps; therefore, providing completion dates for these earlier steps that are at a later date than the later steps. Moreover, it was noted that information for a number of steps may simply be missing from the database; in one case, it was discovered that not all future funding had been entered into the database. The above challenges highlighted the fact that some of the data in the IEMS database appeared to be incomplete or inaccurate.

Mitigation: The statistics provided from the IEMS database were reviewed with a level of caution, including their validity, and, to the extent possible, the data were cleaned. As well, by using multiple and complementary sources of data, including qualitative information, the evaluation team was able to confirm through its analysis the accuracy of key findings.

2.3 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of INAC's Audit and Evaluation Sector managed and completed the evaluation according to EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process, which is aligned with the Treasury Board Secretariat's Policy on Evaluation.

3. Evaluation Findings – Relevance

The key findings regarding the relevance of the program focus on continued need and alignment with the priorities, roles and responsibilities of the federal government as a whole.

3.1 Continued Need

Finding 1: Central arguments for the continuation of INAC's Contaminated Sites On-Reserve Program include the number of contaminated sites on-reserve, the need to address the challenges to environmental, health, and social development in on-reserve communities, a shortage of funding, the need for further capacity development, and the importance of economic development in on-reserve communities.

In 2002, the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development released a report identifying a need for the federal government to move forward with work on contaminated sites in order to ensure their proper management. In response, the Government emphasized the importance of creating a Contaminated Sites On-Reserve Program and in 2005, established the FCSAPFootnote 27 program.

Since 2005, the federal government, through FCSAP, has been engaged in the management of federal contaminated sites acting both to protect human and environmental health. As the literature shows, remediation of contaminated sites and the eventual redevelopment of the land accomplishes a number of important goals such as reducing environmental contamination and site hazards, thereby improving public health and safety while enhancing community members' quality of life through neighbourhood revitalization and conservation of green space.

According to documents reviewed, there were an estimated 6,200 suspected or known contaminated sites in 2005. The Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory, a standardized national database for all contaminated sites under federal jurisdiction, stated that there are presently 2,604 suspected sites and 5,786 active sites under federal jurisdiction. Of these, INAC's CSOR is responsible for 844 suspected and 1,109 active sites. In comparison, INAC's North of 60º program is responsible for 40 suspected sites and 252 active sites, although the northern sites are, in general, more technically complex and generally represent a much higher liability. It is noteworthy that FCSAP does not cover sites that were contaminated post-1998 nor most sites classified as Class 2 or 3Footnote 28. As of March 2013, Contaminated Sites On-Reserve manages 2,392 active contaminated sites on-reserves south of latitude 60˚N. Of the 2,392 sites, 293 are high risk to human health and safety.Footnote 29

Evaluators ascertained as well from key informants across all respondent groups the continued need for the CSOR with INAC interviewees noting that funds obtained from FCSAP has continually been a primary source of funding to either initiate or enable work on contaminated sites to continue.

Further to the preceding information, documents reviewed show that a total of 1,008 sites have been added to the IEMS between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2014 (i.e., the evaluation period); that is, omitting sites that are being managed by other federal departments, which are provincial/territorial responsibility, or are third party responsibility. The most sites have been added in Manitoba (35 percent), Saskatchewan (34 percent) and British Columbia (26 percent) in that time period.

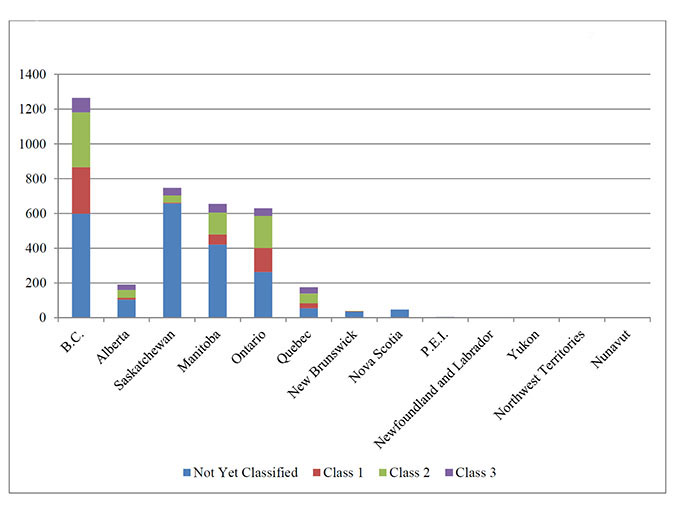

Graph 1, below, reinforces the need for the CSOR.

Graph 1: Contaminated Sites by Province, 2015-2016

*Data based on site classification in the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory.

Text alternative for Graph 1: Contaminated Sites by Province, 2015-2016

This graph shows contaminated sites by province. The number of contaminated sites is indicated along the vertical y axis for the provinces indicated on the horizontal x axis. The provinces with the most sites not yet classified are British Columbia (850), Saskatchewan (around 650), Manitoba (500), Ontario (around 300), Alberta and Quebec (just below 200). New Brunswick and Nova Scotia are both around 50 while PEI, Newfoundland and Labrador and the territories do not have any sites identified on the graph.

The provinces with the most Class 1 sites are British Columbia (600), Saskatchewan (around 650), Manitoba (just above 400), Ontario (around 400), Alberta (100), Quebec (50). New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. PEI, Newfoundland and Labrador and the territories do not have any sites identified on the graph.

The provinces with the most Class 2 sites are British Columbia (1200), Saskatchewan (around 700), Manitoba and Ontario (600), Alberta (100), Quebec (50). New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. PEI, Newfoundland and Labrador and the territories do not have any sites identified on the graph.

The most Class 3 sites are in British Columbia (above 1200), followed by Saskatchewan (just above 700), both Manitoba and Ontario (just above 600), and Alberta and Quebec (just below 200). New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, PEI, Newfoundland and Labrador and the territories do not have any sites identified on the graph.

Graph 1 above offers evidence of a continued need for the program. With funding for assessment decreasing, the number of "Not-yet classified" sites represents a large proportion of the number of sites for which the Department is responsible and although there are more Class 2 sites than Class 1 sites, certain regions still have a number of high-risk sites to deal with. On-reserve contaminated sites, which are typically caused by fuel-related practices (63 percent) or landfill / waste sites (34 percent), continue to be added to the inventory. With constant additions of suspected sites and decreased funding for assessment overall, on top of the ongoing need to remediate the number of high-risk and medium-risk sites left, the data suggest that there is a strong need for the program.

According to environmental liability data extracted from the 2014-15 Public Accounts of Canada, INAC's liabilities of approximately $2.6 billion as of March 31, 2014, represent 56 percent of federal environmental liabilities (see Appendix C: Table 1 for a breakdown of environmental liabilities by custodian department). However, this amount represents the liability for INAC as a whole, a combination of both CSOR and the North of 60- programs. On its own, CSOR liabilities amounted to approximately$211.8 million. This represents 8.1 percent of the Department's total environmental liabilities and 4.6 percent of the total federal environmental liabilities, placing CSOR fourth highest in terms of federal environmental liabilities.

The literature review, site visits and key informant interviews identified numerous examples of contaminated sites on-reserve and an emerging pattern of sites originating after the 1998 FCSAP eligibility date. Given the large number of newer sites not currently funded under FCSAP, dedicated resources to deal with them will be required. In addition, site visit and key informants also suggested there is a need not only for funding assessment and remediation of contaminated sites but also a need to identify a process for promoting environmental stewardship.

3.2 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding 2: There is strong alignment between INAC's Contaminated Sites On-Reserve Program's objectives and federal roles and responsibilities including contaminated sites. This is evidenced in the consistency with federal legislation as well as roles and responsibilities that pertains to environmental matters.

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 provides that "Indians and Lands Reserved for Indians" are a federal responsibility subsequently given effect in the Indian Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. I-5. This creates a unique series of obligations for the Government (and thereby INAC) with regard to the environmental management of on-reserve lands. INAC is the administering department for the Indian Act and herein lie the origin and foundation of the CSOR's alignment with federal roles and responsibilities.

The federal government is responsible for all environmental protection-related legislation and regulation on-reserves managed under the Indian Act. In addition, its powers with regard to the environment are set out in the Fisheries Act, administered by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, and the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, both of which fall under Environment Canada's jurisdiction.

A further legal consideration that aligns the CSOR with federal roles and responsibilities is the requirement for INAC to ensure that its land and environmental management activities are carried out in a sound environmental manner in accordance with the federal government's environmental legislation. Sections 273 and 280 of Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, for example, state that any officer, director or agent of a government department found to be in contravention of the Act or its Regulations may be fined up to one million dollars or given up to three years in prison. The primary purpose of Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 is stated as "to contribute to sustainable development through pollution prevention" and under it the federal government may enact regulations to control risks from substances that have been officially classified as toxic. Moreover, some Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 provisions apply only to First Nations, including, for example, those dealing with environmental management on Aboriginal lands.Footnote 30

The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012) also affects the contaminated sites program. Prior to the new Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012Footnote 31, the remediation of contaminated sites on federal lands required a federal environmental assessment. Thus, on-reserve projects that involved the expenditure of federal funds or that needed federal authorization had to have an environmental assessment in order to obtain such an authorization. Under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, there is no longer a mandatory requirement for a federal environmental assessment. However, the Minister of the Environment may designate specific federal remediation activities and require a federal environmental assessment based on the potential for adverse environmental effects or public concern about those effects. Moreover, all projects are expected to be subject to the appropriate level of environmental assessment as required under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 or its equivalent. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 introduces a streamlined approach that ensures necessary environmental assessments are completed in a timely manner.

As seen earlier under Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries, FCSAP, which is led by Environment Canada, is a federal contaminated site program and is cost-shared, assisting federal custodian departments, agencies and consolidated Crown corporations to address contaminated sites for which they are responsible. It is also a source of funding for the CSOR, which points out the federal government's role and responsibility. Most (two thirds) of FCSAP sites are either situated near or located on federal real property. Of these sites, a quarter is located on designated Canada Lands such as reserves. Less than 10 percent of sites are located on non-federal lands where there is federal responsibility for contamination due to federal activities or those of a lessee, policy decision or contractual obligation.Footnote 32

As a further linkage, the Government of Canada's contaminated sites management policy is overseen by the Treasury Board Secretariat and one aspect of the FCSAP involves Treasury Board Secretariat maintenance of the Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory. The information stored in the inventory includes site location, contaminants, quantity of contamination, proximity to human population and the current status of each site. Moreover, each federal department or agency with responsibility for federal lands is also responsible for identifying, assessing, managing and remediating contaminated sites on their lands in accordance with policies they are required to develop.

Alignment of the program with federal roles and responsibilities is evidenced by INAC's responsibility for 82 percent of classified sites that are on-reserve. While 17 percent of all on-reserve contaminated sites are the responsibility of third parties, implying that the polluter was neither INAC nor the band, one percent of all on-reserve contaminated sites can be attributed to, and are the responsibility of, another federal department or a provincial/territorial government.

Currently, INAC has three key federal partners, which provide expert support: Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Health Canada. Although the roles and responsibilities of each department vary, all act to ensure compliance with legislation on those crown lands that fall under their jurisdiction.

While the CSOR aligns with federal roles and responsibilities, it also aligns with the role of other stakeholders. Thus, First Nations communities are responsible for implementing contaminated sites remediation/risk management projects and developing potential economic benefits for their communities.

In reviewing First Nations and provinces' roles and responsibilities, the issue of the "regulatory gap" arises in that both the federal and provincial governments possess the authority to manage various aspects of the environment, including land use planning and commercial activities. Thus, provincial governments manage provincial lands while the federal government manages federal lands (including Aboriginal lands). Provincial governments, through their responsibility for local matters, have developed environment-related legislation and regulation to manage environmental issues. However, as noted above, provincial legislation and regulations do not apply on Aboriginal lands.

The 2009 Fall Report of the Auditor General observed that the environmental regulatory gap was particularly significant for First Nations that entered into the First Nations Land Management Act regime. The report also noted thatwhere a First Nation enters into this regime, it was responsible for closing any identified environmental regulatory gap that existed on its territory. Thus, with the lack of federally enacted legislation on-reserve with respect to environmental protection, a "regulatory gap" exists when compared to other Canadian communities. In the case of remediation and recovery of remediation costs of contaminated sites, an example of a regulatory gap on-reserve is the lack of appropriate laws, which should govern industrial, commercial or other such activities. While federal environmental statutes and policies do not appear to provide the same degree of protection on-reserve as do provincial environmental laws for off-reserve lands, under Part 9 of Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 there are regulations on registration of storage tank systems for petroleum products and allied petroleum products which may touch on contaminated sites on-reserve.

3.3 Alignment with Federal, Departmental and Community Priorities

Finding 3: The CSOR Program is aligned with Federal, Departmental and Community Priorities, as evidenced in announcements and commitments made by the federal government and INAC, which confirm Community priorities (the use and management of reserve lands) and that CSOR's objectives remain key priorities.

The CSOR Program's Alignment with Federal Priorities

As shown above (e.g., FCSAP), the CSOR is explicitly linked to the federal government's roles and responsibilities with respect to environmental management such as contaminated sites. In addition to FCSAP's original funding of $3.5 billion over 15 years announced in Budget 2004, the federal government has renewed support for the action plan through two additional funding endowments: the 2009-2010 Canada Economic Action Plan; and Budget 2011. In the case of Budget 2011, the federal government outlined its long-standing support of contaminated sites remediation stating that "The Government has developed a long-term Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan to systematically assess, remediate and monitor sites for which the Government is responsible." The 2013 Speech from the Throne also addressed the third expected result of the CSOR, stating:

- "Canadian families expect safe and healthy communities […] and enjoy a clean and healthy environment"

- "our Government will continue to work in partnership with Aboriginal peoples to create healthy, prosperous, self-sufficient communities" (Government of Canada, 2013b).

FCSAP Phase III is set to begin in 2016, a further indication that federal contaminated sites constitute a serious priority for the federal government. This is, moreover, reinforced by the fact that the CSOR represents a significant portion of total liabilities, works closely with the FCSAP partner departments and is clearly aligned with federal priorities.

Graph 2 below highlights the significance of FCSAP in terms of alignment with federal priorities. As depicted by the graph, the CSOR, in most years, and especially in recent years, receives a higher proportion of FCSAP expenditures than its relative proportion of liabilities. This suggests that the CSOR's liabilities are a high priority for the federal government and are consequently well supported by FCSAP funds. It should be noted that, based on the literature review and key informant interviews, as well as the nature of the assessment, remediation and monitoring services procurement on-reserve, on-reserve contaminated sites may be socially more complex and in harder to remediate areas, thus justifying a need for more funding than sites that fall under other departments' jurisdiction. NOTE: the higher proportion does not mean that the CSOR receives sufficient funds.

Graph 2: INAC's South of 60º Contaminated Sites On-Reserve in Relation to Total Liabilities and Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan Spending

Source of "Percent of Total FCSAP Spending" – Federal Contaminated Sites Inventory

Source of "Percent of Total Liabilities" – Appendix C, Table 1: Breakdown of Environmental Liabilities by Custodian Department

Text alternative for Graph 2: INAC's South of 60º Contaminated Sites On-Reserve in Relation to Total Liabilities and Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan Spending

Line Graph 2 highlights the significance of FCSAP in terms of alignment with federal priorities. It shows INAC's CSOR in relation to total liabilities and FCSAP spending. The proportion of FCSAP expenditures is indicated along the vertical y axis for the years indicated on the horizontal x axis. The years are from 2007-08 to 2012-13 and the 2 lines indicate the percent of total FCSAP spending (line with intermittent small squares) and the percentage of total liabilities (line with intermittent large squares). In 2007-08 to 2008-09, liabilities rose from 0.04 to 0.1, then started dropping, down to just above 0.04 in 2012-13. In 2007-08 to 2008-09, expenditure rose from 0.06 and peaked 0.15 in 2010-11, then started dropping, down to 0.1 in 2011-12, then rose again to 0.12 in 2012-13.

In addition to FCSAP, one example of how the CSOR aligns with the federal government's priority regarding contaminated sites can be found in Chapter 3 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development's 2012 Spring Report. The report reviewed the status of federal contaminated sites, including sites on First Nations reserves. According to the report, contaminated sites do not only affect soil, water, and air integrity, but also have the potential to and may jeopardize the health of people who live or work near these sites. Furthermore, the report indicated that contaminated sites may harm natural flora and fauna. Thus, without remediation, the sites' negative effects could continue indefinitely since some of the contaminants, ranging from toxic and hazardous substances such as petroleum products to heavy metals and radioactive materials, are considered to be extremely persistent. Key informants and site visits to reserves confirmed these concerns.

The CSOR Program's Alignment with Departmental Priorities

It is important to note in relation to Aboriginal community priorities that there are 615 First Nations and over 80 percent have fewer than 1,000 people living on-reserve. Moreover, First Nations, particularly those living on-reserve, have higher unemployment rates and lower average incomes in comparison to other Canadians. Thus, with various First Nations viewing the development of reserve lands as either one of, if not the most viable means of generating wealth for their communities (e.g., developing natural resources or leasing parcels of land to others, activities that spur economic development), contaminated sites do not augur well for such development. Furthermore, as reserve site visits showed, First Nation communities include homes, schools, churches, administration buildings, all of which are built on-reserve land and foster social development. The presence of contaminated sites, therefore, adversely affects communities.

Sustainable development (economic or otherwise) of reserve lands depends on First Nations' access to and control over their land and natural resources, including a clean and healthy environment. Thus, contaminated sites impact reserves' interests and remain a major barrier to economic and community development. In some areas, for example where development is expected and when the "shovel hits the ground," sites have to be abandoned because of the discovery of contamination. This, in turn, results in years of delay in developing the resource. Responsible development and use of natural resources has the potential to promote job creation and attract skilled resources and also to succeed, not only in the Canadian but also in the global economy. Contaminated sites deter progress, as case studies undertaken for this evaluation have shown and even economic development is adversely impacted if on-reserve land must be taken out of productive use.

Addressing contaminated sites on-reserve lands is expected to help in the attainment of development goals while also supporting government priorities related to Aboriginal training and employment. Reserve site visits showed that contaminated site management projects offer Aboriginals benefits in terms of work opportunities, skill development and knowledge-based career potential.

Where the reserve community lacks the capacity, the opportunity and the help, as well as the wherewithal, to develop and use its lands and resources sustainably for the community's benefit, then that particular First Nation reserve's community is deprived of an improved quality of life. In turn, the community is unlikely to approach the standard of health and wellbeing that other Canadian communities enjoy.

Departmental Priorities: Northern Contaminants Program - the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut

While this evaluation excluded the Northern Contaminants Program (which includes the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut), a brief comparison of the North and South of 60º programs may be useful in the context of the departmental priorities.

First, the nature or source of contamination sites in the South of 60º is mainly fuel storage and handling (67 percent), solid waste/landfills (20 percent) and other (13 percent) whereas in the North of 60º, past private sector resource extraction and military activity account for the contamination problem.

Second, in the South of 60º, contaminated sites are on-reserve, numerous, much smaller in size, tend to be within or in the close vicinity of communities, represent smaller financial liabilities, and new sites are expected to discovered anytime. Contaminated sites under Northern Contaminants Program management are fewer, large-sized, have a tendency to be far removed or are not in close proximity (i.e. in remote locations, away from any settlements), do not expect a significant increase in the number of new sites, and costly in terms of remediation efforts (Northern Contaminants Program sites are usually abandoned northern mine sites that will extend beyond FCSAP (2020).

The relative success of the North of 60º Northern Contaminants Program compared to the CSOR was identified as an issue by previous audits and program evaluations. A specific issue arose from the 2008 evaluation of both the North and South components of INAC's contaminated sites program, namely, a lack of dedicated funding on an annual basis made it difficult for both halves of the program to plan and prepare their site assessments and remediation processes accordingly. This was especially challenging with respect to the CSOR because funding is passed along to communities, adding an additional step between the funding source and the final contracting of services. In response to a recommendation made by the 2008 evaluation, the program has allocated some dedicated A-base funding for the program.

The evaluation also found that the placement of both the North and South contaminated site programs within the Department highlights how these two sub-programs are prioritized. For example, the fact that the CSOR is situated with the Lands and Economic Development Sector provides some indication about the role that the CSOR plays in ensuring that reserve land, aside from being healthy to live on or near, is effectively available for any economic development opportunities the community may want to pursue with it. Economic development for First Nations is a fundamental departmental priority, thus, the placement of the CSOR with the Lands and Economic Development Sector indicates the importance of assessing and remediating contaminated sites in order to create a healthy economic development environment.

Based on interviews conducted, however, some challenges regarding support (number of staff and funds) for the program exist. The evaluation found significant staff support for the CSOR, but the variability of program staff and resource availability for program delivery differ considerably across regions. Interviews with regional staff revealed that a number of environmental officers are handling both their CSOR responsibilities and other program duties as well. Accordingly, staff dedicated to CSOR in some instances could be as few as one individual. Regional staff also noted that since FCSAP funding is unavailable for new sites or sites that are not high-risk, resources were often under pressure in attempting to deal with non-FCSAP sites. As shown in Graph 1 (number of sites by classification across provinces), most regions are dealing with a number of class 2 and 3 and unclassified sites. There was some expectation among interviewees that possible changes in Phase III of the FCSAP program might address some of these resource needs. Despite a lack of financial resources, the regions noted, almost unanimously, that they felt well supported by Headquarters when funding was needed, identifying the national CSOR coordinator as particularly strong in helping to secure resources.

In summary, although distinctions exist between the contaminated sites that are North and South of 60º, with most (93 percent) of INAC's liabilities for contaminated sites found North of 60º, lessons learned from the latter can be applied to the South of 60º program. For instance, by adapting or using the contribution to scientific knowledge and expertise developed as part of the northern remediation efforts. See Section 6, "Other Findings/Observations" for more on this topic.

The CSOR Program's Alignment with Community Priorities

As noted, communities prioritize contaminated site clean-up differently, depending on other pressing issues they may be dealing with. The sheer numbers of suspected contaminated sites communities have identified and that are yet to be addressed points to the concern that on-reserve communities have regarding contamination.