Evaluation of the Investment in Economic Opportunities

February 2015

Project Number: 13072

PDF Version (702 KB, 61 Pages)

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- Section One: First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act

- 3. Relevance - FNCIDA

- 4. Effectiveness - FNCIDA

- 5. Efficiency and Economy - FNCIDA

- Section Two: Community Economic Opportunities Program

- 6. Relevance - CEOP

- 7. Effectiveness - CEOP

- 8. Efficiency and Economy - CEOP

- Section Three: Conclusions and Recommendations

- 9. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A – Logic Model - 3.2.2 Investment in Economic Opportunities

- Appendix B – Economic Context

Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| CEOP |

Community Economic Opportunities Program |

| CORP |

Community Opportunity Readiness Program |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation and Performance Measurement Review Branch |

| FNCIDA |

First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act |

Executive Summary

Investment in Economic Opportunities provides critical support for communities to support greater Aboriginal participation in large and complex economic opportunities. Targeted investments through the Community Economic Opportunities Program provide funding for First Nation and Inuit communities for a range of activities to support communities' pursuit of economic opportunities. The First Nation Commercial and Industrial Development Act includes the adoption of regulations for complex commercial and industrial development projects. These activities provide crucial support to First Nation and Inuit communities in their partnership development with the private sector and other levels of government to effectively participate in, and benefit from, such economic opportunities. Program components within Investment in Economic Opportunities are the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA) and Community Economic Opportunities Program (CEOP).Footnote 1

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) conducted an Evaluation of the Investment in Economic Opportunities. The overall purpose of the evaluation is to provide reliable evaluation evidence that will be used to support policy and program improvement and, where required, expenditure management, decision making, and public reporting related to the Strategic Outcome The Land and Economy. The Terms of Reference for the evaluation were approved at AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on November 22, 2013.

The evaluation supports the following conclusions and recommendations:

Relevance

FNCIDA and CEOP align with the federal government priorities as articulated in the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and fall within the jurisdictional scope of the federal government. FNCIDA addresses existing regulatory gaps for large capital investment for First Nations on-reserve, which allows First Nations to pursue large-scale projects with the potential for significant economic benefits. CEOP addresses many barriers faced by First Nation and Inuit communities when pursuing economic development.

Effectiveness

FNCIDA has the potential for creating opportunities for economic development projects, which have the possibility of generating large revenues for First Nations through increased investment, employment and business opportunities on-reserve. While some early success has been demonstrated, complex economic development projects, like those undertaken through FNCIDA, will require a significant amount of time before they can fully demonstrate results.

CEOP has funded a wide range of projects, which have demonstrated positive results, including increase in employment of community members, community business development, and development of lands and resources.

In order to ensure transparency and demonstrate sound stewardship, the Assistant Deputy Minister, Lands and Economic Development Sector, with the support of the Chief Financial Officer, should ensure that a full reconciliation between Main Estimates and actuals is performed on a regular basis and any difference is explained and accounted for properly.

Efficiency and Economy

FNCIDA remains the best approach to address regulatory gaps on-reserve. In order to harmonize laws applicable to commercial and industrial projects on-reserve lands with those applicable on provincial lands, the regulations require a high level of control and accountability. Details regarding enforcement issues and responsibilities of each party need to be negotiated and pre-determined prior to project implementation. FNCIDA, through its system of regulations and tripartite agreements, provides this level of assurance. There was an underestimated level of effort and resources required as preparing the regulation and negotiating the tripartite agreement for some projects is requiring a significantly longer time period than initially anticipated. Although some efficiencies have been implemented to counter this, including the development of templates for standardizing elements of the tripartite agreements, there are areas in which further efficiencies can be realized. For example, the work put in to create a regulatory regime under FNCIDA, while being limited in application to the project lands, can be adapted to apply to similar projects within the same province. In a similar vein, the negotiation of tripartite agreements is expected to become less onerous once a province has previously participated in the process. In addition, the preparation and drafting of regulations can be adapted to facilitate similar First Nations projects in the future.

The evaluation found that as a result of the changes to the operating environment in the Lands and Economic Development Sector, including the Economic Development program suite renewal which saw CEOP and other Lands and Economic Development programs consolidated into the Community Opportunity Readiness Program (CORP), many of the issues related to approval processes and overlap and duplication were removed and more efficiency was realized. CORP is providing a more focused approach to project-based funding for a range of activities to support communities' pursuit of economic opportunities.

Recommendations

- As part of the Performance Measurement Strategy, design and implement performance measures and indicators which provide metrics to objectively evaluate and demonstrate both the short term and longer term impact of Investment in Economic Opportunities.

- Ensure that efficiency and economy are being realized as the work to adopt regulations under FNCIDA facilitates the preparation and drafting of regulations for other First Nations projects.

- Ensure that CORP continues to work as part of a continuum of economic development programs within AANDC to support economic opportunities for First Nation and Inuit communities.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Investment in Economic Opportunities

Project #: 13072

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. As part of the Performance Measurement Strategy, design and implement performance measures and indicators which provide metrics to objectively evaluate and demonstrate both the short term and longer term impact of Investment in Economic Opportunities. | LED has completed a Performance Measurement Matrix for the Investment in Economic Opportunities sub-program, as part of the development of the Performance Measurement (PM) Strategy. The PM Strategy was approved by the Evaluation and Performance Measurement Committee on March 20, 2014, and is now being implemented. LED will update the PM Strategy to include a risk assessment as well as refine the performance indicators to better support the monitoring and reporting of FNCIDA and CORP results. |

Director General, |

Implementation Date: PM Strategy 3.2.2 approved March 20, 2014 Completion Date: Risk Assessment – September 2015 Updated PM Strategy 3.2.2 - |

| 2. Ensure that efficiency and economy are being realized as the work to adopt regulations under FNCIDA facilitates the preparation and drafting of regulations for other First Nations projects. | Based on the development of four FNCIDA projects, we are revising our internal procedures and producing guidelines and templates in order to expedite regulatory development in future FNCIDA projects as follows: a) The Project Management Team is streamlining the process by which FNCIDA project proposals are developed, reviewed and approved to reduce the amount of paperwork required, while focusing on analyzing the criteria essential to a successful project. Furthermore, internal processes for regulatory development and approval are also being revised with the objective of benefiting from past lessons learned. New process documents being developed for internal and external use will aim to reduce time taken by bureaucratic processes. b) A model for the tripartite agreement entered into between the province, Canada and the relevant First Nation in order to govern the administration of the FNCIDA regulations has been developed. This model is based on analysis of the provisions of completed agreements and determination of best practices based on discussions with those who participated in the development of completed agreements. For instance, the issue of liability of provincial government officials arises in each project and has been addressed anew; in future projects, analysis of this issue and a suggested provision vetted by legal counsel and senior management is provided. As new FNCIDA projects are commenced, Canada will have a template of provisions to propose to the other parties and rationales based on past experience which should expedite the process of negotiating the agreement. c) A guiding principles document addressing the legal issues that arise in developing drafting instructions for a regulatory regime that relies on incorporation by reference is in development. While the provincial regulations being analyzed for incorporation will be unique in each FNCIDA project, many of the main legal issues will be common. For instance, in each FNCIDA project, a key point of analysis will be to understand which provincial authorities are approving and acting on behalf of the provincial Crown and whether in all instances they can be used for the purpose of the federal FNCIDA regulations, or not. Commentary on what these issues are, where to look for them in the analysis of provincial regulations and how to resolve them will help expedite the drafting of future FNCIDA regulations. We will continue to review our procedures as FNCIDA projects are assessed and developed, with a view to further increasing economies and efficiencies. |

Director General, |

Implementation Date: Underway a) and b) currently in place but being reviewed and revised Completion Date September 2015 |

| 3. Ensure that CORP continues to works as part of a continuum of economic development programs within AANDC to support economic opportunities for First Nation and Inuit communities. | Through Lands and Economic Development Services Program, support First Nations in planning and capacity building so they can effectively respond to economic opportunities. Develop internal and external communications strategies to assist in promoting the continuum of economic development programming available to First Nations. |

Director General, |

Implementation Date: Underway Completion Date April 2015 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed by:

Sheilagh Murphy

Assistant Deputy Minister, Lands and Economic Development

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

As per Treasury Board requirement to evaluate program spending every five years, the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) conducted an Evaluation of the Investment in Economic Opportunities.

The overall purpose of the evaluation is to provide reliable evaluation evidence that will be used to support policy and program improvement and, where required, expenditure management, decision making, and public reporting related to the Strategic Outcome The Land and Economy.

The evaluation will provide evidence-based conclusions and recommendations regarding relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) as per the Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation.

The report's findings are divided into three sections: Section One – First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA) component, Section Two – Community Economic Opportunities Program (CEOP) component, and Section Three - Conclusions and Recommendations. The evaluation report begins with a program profile and details the methodology undertaken for this evaluation.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Investment in Economic Opportunities provides critical support for communities to support greater Aboriginal participation in large and complex economic opportunities. Targeted investments through the Community Economic Opportunities Program provide funding for First Nation and Inuit communities for a range of activities to support communities' pursuit of economic opportunities. The First Nation Commercial and Industrial Development Act includes the adoption of regulations for complex commercial and industrial development projects. These activities provide crucial support to First Nation and Inuit communities in their partnership development with the private sector and other levels of government to effectively participate in, and benefit from, such economic opportunities.

Program components within Investment in Economic Opportunities are as follows:

- First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act

- Community Economic Opportunities ProgramNote de bas de page 2

First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act

FNCIDA was introduced in the House of Commons on November 2, 2005, and came into force on April 1, 2006. This legislation was needed to close the regulatory gap on-reserves and allow complex commercial and industrial projects to proceed. FNCIDA allows the federal government to produce regulations for complex commercial and industrial development projects on-reserves. The Act essentially provides for the adoption of regulations on-reserve that are compatible with those off-reserve. This compatibility with existing provincial regulations increases certainty for the public and developers while minimizing costs.

Federal regulations are only made under FNCIDA at the request of participating First Nations. The regulations are project-specific, developed in cooperation with the First Nation and the relevant province, and are limited to the particular lands described in the project. These regulations allow the federal government to delegate monitoring and enforcement of the new regulatory regime to the province via an agreement between the federal government, the First Nation and the province.

In 2010, FNCIDA was amended by Bill C-24, the First Nations Certainty of Land Title Act. The amendments to FNCID allow on-reserve commercial real estate projects to benefit from greater certainty of title. The amendment will allow First Nations to request that their on-reserve commercial real estate projects benefit from a property rights regime, including a land title system and title assurance fund, identical to the provincial regime off the reserve. The certainty of land title granted by such a regime would increase investor confidence, making the value of the property comparable with similar developments off the reserve.

FNCIDA is intended to open up opportunities for economic development projects that will generate prosperity for First Nations and create much needed jobs. Investors will have greater certainty about the regulations involved in developing major commercial or industrial projects on-reserve, improving First Nations' prospects for attracting major capital investment. First Nations will benefit from a greater potential rate of return from their investments and from increased employment and business opportunities on their reserves. Provinces benefit from uniformity of regulations concerning major commercial and industrial development within their borders. Major commercial and industrial projects on-reserve will be appropriately regulated to address health, safety and environmental considerations.

By providing for regulatory certainty, FNCID is intended to help to more effectively balance economic development with environmental protection and social policy goals, promoting the sustainable use of reserve lands and resources for future generations. Also, major commercial and industrial projects contribute to the economy of the surrounding region, increasing employment, generating tax revenue and benefitting all Canadians.

CEOP

CEOP provides project-based, proposal driven support to those First Nation and Inuit communities with identified economic development opportunities, which would have significant economic benefits for their respective communities.

Eligible projects address the following:

- employment of community members;

- community and entrepreneur business development;

- development of land and resources under community control;

- access to opportunities originating with land and resources beyond community control;

- promotion of the community as a place to invest; and

- research and advocacy.

CEOP is expected to lead to community economic benefits, including more community employment and related incomes, greater utilization and increased value of land and resources under community control, more community government revenue from economic development, enhanced community economic and other infrastructure, more and better arrangements to access off-reserve resources, more investment in the community, a better climate and environment for community economic development, more and larger community businesses, more contracts and sales for community businesses, and enhanced capacity within the community government to address future economic opportunities.

Program renewal and consolidation in 2014 led to CEOP becoming the Community Opportunity Readiness Program (CORP).

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

Investment in Economic Opportunities is sub-program 3.2.2 situated under the Lands and Economy Pillar / Community Development Program of the 2014-2015 Program Alignment Architecture.

Expected Result

Private sector partnerships and investments occurring within First Nation and Inuit communities.

Performance Indicators

- Projected leveraging investments within First Nation and Inuit communities

- Length of time needed to prepare the federal regulatory proposal allowing partnerships and investments (which includes the regulations as well as the tripartite agreement)

A Performance Measurement Strategy is in place for 3.2.2 Investment in Economic Opportunities, dated March 20, 2014. The logic model for this sub program area is found in Appendix A of this report.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

FNCIDA

Program Management: A First Nation brings forward a regulatory proposal, often with an industry proponent, and participates as an active member in both the development and delivery of the project regulations and associated Tripartite Agreement.

AANDC Headquarters and regional staff work cooperatively regarding policy research, decisions regarding FNCIDA project specific prospective, and senior level briefings. AANDC Headquarters staff within the FNCIDA Project Management Office provides program management services, including reviewing proposals, delivery oversight, including the development and tracking of annual plans, resource planning, management and reporting services, policy, and governance as well as participates in the negotiation of the Tripartite Agreement. AANDC regional staff provides day-to-day project delivery by working closely with the First Nation, the proponent (i.e. private sector business investor), the province, industry, the Department of Justice, as well as with AANDC Headquarters. Regional staff also participates in the negotiation of the Tripartite Agreement.

The Regulatory Drafting Section of the Department of Justice and departmental legal counsel are involved in drafting the Tripartite Agreement, the regulations, and any necessary changes in the regulations to mirror relevant changes made in the provincial statutes.

Provincial government representatives are involved in the negotiation of a Tripartite Agreement with the federal government and the First Nation, as well as in providing their input to the draft regulations.

Key Stakeholders: The proponent First Nation(s) are the key stakeholders in each FNCIDA project. Other stakeholders include provincial governments, project proponents (i.e. private sector business investor), industry, First Nation organizations, and municipalities.

Intended Beneficiaries: The primary beneficiaries of FNCIDA projects are the proponent First Nation(s) and their members who are expected to gain from economic development, increased capacity building, and employment opportunities on their reserves. Industry proponents and investors benefit from the revenues of the projects and increased certainty due to the establishment of a seamless regulatory regime on- and off-reserve, with respect to human and environmental health and safety as they pertain to the project.

CEOP

Program Management: AANDC Headquarters staff are responsible for the design and development of CEOP, including developing program guidelines, tools and other resources to assist AANDC regional offices and communities in delivering the programs and reporting on results. AANDC regional staff is responsible for the delivery of CEOP. They support communities in the delivery of their core services and capacity building efforts. They also manage the proposal based programs and jointly review and assess, with AANDC Headquarters, large scale projects where the amount of funding requires Headquarters approval.

Key Stakeholders: The individual First Nations and Inuit communities involved with CEOP project are the key stakeholders. Other stakeholders include representative organizations of Inuit communities, and other organizations that have designation and mandates to carry out economic development activates in First Nation and Inuit communities.

Intended Beneficiaries: First Nation and Inuit communities receiving the benefits from CEOP project funding.

1.2.4 Program Resources

| Actual Fiscal Year 2013-14 | Main Estimates 2014-15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CEOP / CORPFootnote 3 | Grants and Contributions (Vote 10) | 28.260 | 41.325 |

| Operating (Vote 1) | .747 | 2.224 | |

| Statutory Operating Capital | - | 1.500 | |

| Total | 29.007 | 45.049 | |

| FNCIDAFootnote 4 | Operating (Vote 1) | .298 | 1.921 |

| Total | .298 | 1.921 | |

| Total 3.2.2 Investment in Economic Opportunity | Grants and Contributions (Vote 10) | 28.260 | 41.325 |

| Operating (Vote 1) | 1.045 | 4.145 | |

| Statutory Operating Capital | - | 1.500 | |

| Total | 29.305 | 46.970Footnote 5 |

| 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | Main Estimate | Actual | |

| CEOP | 55.725 | 13.046 | 54.830 | 17.599 | 48.980 | 22.558 | 49.002 | 25.686 | 49.354 | 23.807 | 45.191 | 29.007 | 303.082 | 131.704 |

| FNCIDAFootnote 6 | 3.921 | .515 | 2.708 | .317 | 1.948 | .458 | .134Footnote 7 | .550 | 2.439 | .407 | 2.103 | .298 | 13.253 | 2.545 |

| Total | 59.646 | 13.561 | 57.538 | 17.916 | 50.928 | 23.016 | 49.136 | 26.236 | 51.793 | 24.214 | 47.294 | 29.305 | 316.335 | 134.249 |

| Difference (Main Estimates greater than Actual expenses for fiscal year 2008/09 to 2013/14) | $182.086M | |||||||||||||

The financial authority associated with Investment in Economic Opportunities is Contributions to Support Land Management and Economic Development.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined the issues of relevance and performance for all the components within sub program 3.2.2 of the 2014-15 Program Alignment Architecture during the period 2008-09 to 2013-14.

The evaluation was conducted by EPMRB with the assistance of the consulting firms Alderson-Gill, which conducted the case studies for CEOP and PRA Inc., which conducted the literature review and case studies for FNCIDA.

The Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on November 22, 2013. Field work was conducted between January and August 2014.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference, the evaluation is focused on the following issues and questions.

2.2.1 Relevance

1. Is there an ongoing need for activities within the sub program 3.2.2 of the 2014-15 Program Alignment Architecture, Investment in Economic Opportunities?

2. Does Investment in Economic Opportunities align with current federal government and AANDC strategic outcomes?

3. Does Investment in Economic Opportunities align with federal roles and responsibilities?

2.2.2 Performance - Effectiveness

4. To what extent has Investment in Economic Opportunities achieved its intended results?

5. Have there been any unexpected impacts (positive or negative)?

2.2.3 Performance – Efficiency and Economy

6. What factors have facilitated or detracted from achieving efficiency and economy?

7. Is there any overlap or duplication with other federal programs and/or other jurisdictions?

8. Are there other more cost-effective ways of supporting Aboriginal economic development?

9. What best practices and lessons learned have emerged?

10. What recommendations can be made towards future performance measurement activities, within what timelines, and will they require tabling with the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee?

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The results of the evaluation are supported by findings that were collected using the following research methods

2.3.1 Literature Review

The evaluation team reviewed 70 academic research and government reports that explored approaches to economic development in Aboriginal communities.

2.3.2 Document and File Review

The evaluation conducted an analysis of program data to gain a better understanding of who are the major recipients and types of projects funded. This analysis identified how the funding was spent, and contributed to the selection of key informant interviews and case studies.

2.3.3 Key Informant Interviews

A total of 66 individuals were interviewed as part of this evaluation from the following groups:

- AANDC Headquarters (n=9)

- AANDC regional offices (n=23)

- Other federal government departments (n=2)

- First Nation and Inuit Program Participants (n=23)

- Provincial governments (n=5)

- Industry (n=2)

- First Nations - Non Participants – FNCIDA (n=2)

2.3.4 Case Studies

FNCIDA (n=5)

- Fort William First Nation – Ontario - Wood Fibre Optimization Plant

- Muskowekwan First Nation - Saskatchewan – Potash Mining Development

- Fort McKay First Nation – Alberta - Oil Sand Mining Project

- Hailsa First Nations – British Columbia Liquefied Natural Gas Facility

- Squamish First Nation – British Columbia – Commercial Real Estate Development

CEOP – Best Practice (n=7)

- Membertou First Nation – Atlantic-– CEOP funds supported commercial and business development

- Conseil Des Montagnais Du Lac St-Jean - Quebec – CEOP funds supported industrial and manufacturing projects

- Nipissing First Nation - Ontario – CEOP funds supported commercial housing and small business projects

- Opaskwayak Cree Nation - Manitoba – CEOP funds supported mining, training, hospitality and website projects

- Flying Dust First Nation - Saskatchewan – CEOP funds supported commercial and corporate development projects

- Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation - Alberta – CEOP funds supported development of reserve lands though land use plan implementation

- Stz'uminus First Nation - British Columbia – CEOP funds supported infrastructure and land use planning projects

CEOP – Stratified Random Selection (n=26 communities encompassing 53 CEOP projects)

- Economic Development Plan Projects (n=20)

- Technical Studies and Engagement Projects (n=11)

- Capacity Development Projects (n=21)

- Economic Infrastructure Project (n=1)

2.4 Quality Assurance

The evaluation was directed and managed by EPMRB in line with the EPMRB 's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process. Quality assurances have been provided through the activities of an advisory group comprising representatives from EPMRB and Lands and Economic Development Sector.

2.5 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Considerations:

- FNCIDA encompasses provincial / federal relationships, which add to its complexity. Moreover, FNCIDA is an Act with no program component.

- CEOP has been restructured and is now the CORP.

- CEOP and FNCIDA are very different program areas. The evaluation dealt with this with distinct component sections, with an overarching conclusion section.

Strengths:

- The evaluation is supporting the departmental Performance Measurement Framework by evaluating within its structure.

Limitations:

- By their nature, results of economic development activities are complex with impacts being evident in the long term, not in the short term.

- Lack of performance data in place to measure program results.

- Lower than anticipated input from First Nation and Inuit communities, who have participated in FNCIDA and CEOP projects, as part of the case study analysis.

Section One: First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act

3. Relevance - FNCIDA

The evaluation looked for evidence that FNCIDA addresses an actual need, is aligned with government priorities, and is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities. Findings from the evaluation point to the evaluation issue of relevance being positively demonstrated as FNCIDA addresses existing regulatory gaps for large capital investment for First Nations on-reserve, which allows First Nations to pursue large-scale projects with the potential for significant economic benefits. FNCIDA aligns with the federal government priorities as articulated in the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and falls within the jurisdictional scope of the federal government.

3.1 Ongoing Need

There is a demonstrated need for economic development on-reserve through key indicators of economic development

Along many dimensions of economic development, such as employment rate, labour force participation and income, Aboriginal communities, and in particular, First Nations individuals living on-reserve, lag behind the rest of Canadians. Access to wealth creation for First Nations is viewed as an essential condition for effectively dealing with the current social challenges that are triggered by poverty and unemployment. See Appendix B for a detailed analysis of economic development indicators for Aboriginal people.

Addresses existing regulatory gap for complex commercial and industrial projects being pursued by First Nations on reserves that creates the condition to attract major capital investment

Prior to FNCIDA, the federal legislative framework in place could not provide parameters that would allow for large capital investments to be done on-reserve. For example, in 2010, the First Nations Industrial Development Act was amended to enable Squamish First Nation to develop land for leasehold condominiums and develop a regulatory regime that replicates British Colombia's land titles system. Without land title certainty, investors faced a potential discount on the value of on-reserve residential properties when compared to equivalent properties off-reserve. The development of a property rights regime, seamless with that off reserve, would increase certainty of land title and ensure a level playing field between on- and off-reserve properties.

Need is limited to those First Nations who are pursing complex commercial opportunities available to them or with significant regulatory gaps preventing major economic development.

Provides economic climate to appeal to potential investors

Implementing economic development projects requires external partners that can contribute to capital investment. FNCIDA enhances the possibility of doing business on-reserve by providing regulatory certainty and thus, removing the disincentive to economic development on-reserve. FNCIDA is intended to move at the speed of business in order to meet commercial timelines. Investors are more willing to undertake projects on-reserve if applicable regulations for their projects mirror those of the provinces in which reserves are located. Investors do not want to take a market discount for doing business on-reserve.Footnote 8Moreover, regulatory uncertainty can prevent the investment communities from even considering undertaking large-scale projects on-reserve.

Allows First Nations to pursue large-scale projects with the potential for significant economic benefits while protecting against potential negative environmental and heath related impacts

The need for FNCIDA is anticipated to grow as the reserve land base grows through additions to reserve. The Additions to Reserve processes and land designations are opening up new economic opportunities. Since 2006, nearly 350,000 hectares of land were added to reserves under the federal Additions to Reserves / New Reserves Policy, a 12 percent increase to the First Nations land base. Whether there is existing industrial and commercial activity on these lands being added to reserve, or the potential for economic opportunities, FNCIDA can be used to bridge the regulatory gaps between on- and off-reserve regimes.

The regulatory framework is critical for protecting First Nation communities against potential negative environmental and health related impacts of economic development opportunities as the nature and scale of large-scale projects First Nations are pursuing on-reserve land is increasing. FNCIDA provides First Nations with appropriate management of potential environmental, health and safety, and other risks associated with large scale, complex commercial and industrial projects.

Enables the federal Crown to balance its responsibilities and potential liabilities as fiduciary with regard to reserve land management along with its desire to promote and support First Nation economic development

While the need to provide an appropriate regulatory framework is often viewed as a critical step for attracting investment, it is also critical for First Nation communities to be protected against potential environmental or health related impacts. FNCIDA reduces risk among First Nations who enter into these types of large-scale industrial projects, but also limits the liability to the Crown from such industrial projects on-reserve.

3.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities

Collaboration with Aboriginal communities in order to facilitate economic development is central priority of the federal government

Various Government of Canada commitments have supported Aboriginal economic development as a government priority. The 2012 Crown-First Nations Gathering committed to unlocking the economic potential of First Nations as a priority. Budgets brought forward by the federal government in 2012, 2013, and 2014 have noted a commitment to Aboriginal economic development. The 2014 Budget noted that there is significant employment and profit opportunities for Aboriginal peoples associated with natural resource development and that the federal government will continue to consult with Aboriginal partners on maximizing opportunities related to resource projects.

FNCIDA aligns with federal government priorities as articulated in the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and Advantage Canada: Building a Strong Economy for Canadians

The Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development succinctly lays out the federal government's priorities and approach in the area of Aboriginal economic development. As noted in the document, the framework is meant to align with Advantage Canada: Building a Strong Economy for Canadians. Advantage Canada is the federal government's long-term national economic policy document developed in 2006.

As the Framework suggests, one of the elements of Advantage Canada is recognition that the government has a role in creating the right conditions for Canadians to thrive in economic prosperity today and in the future. It further acknowledges that building opportunities for Aboriginal people to participate in the economy is the most effective way to bridge the socio-economic gap with other Canadians.

The Framework points to four specific ways in which it aligns with Advantage Canada and the federal government's broader economic development approach. They include:

- Focusing government so that roles and responsibilities are aligned to maximize economic outcomes for Aboriginal people;

- Supporting skills and training that will create new opportunities and choices for Aboriginal peoples;

- Leveraging investment and promoting partnerships with the private sector to produce sustainable growth for Aboriginal peoples; and

- Acting to free businesses to grow and succeed by removing barriers to Aboriginal entrepreneurship and leveraging access to commercial capital.

The Framework also highlights an emerging consensus around the idea that the Indian Act places barriers on economic development and investment on reserves. Further, the Framework identifies four strategic priorities, one of which involves strengthening Aboriginal entrepreneurship. Under this strategic priority, addressing the legislative barriers imposed by the Indian Act is one among these four key government activities.

The regulatory reforms supported through FNCIDA align closely with many of the priorities identified in both Advantage Canada and the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development.

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

FNCIDA falls within the jurisdictional scope of the federal government

The structure created by the Indian Act limits the ability of First Nations to pursue large-scale commercial industrial projects. It is therefore within the scope of the federal government to address this gap. These gaps arise due to the limitations in the Indian Act, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, and other legislation to develop an appropriate federal land and environmental regulatory regime on-reserve.

No overlap between FNCIDA and provincial legislation of general application

Regulations made under FNCIDA are developed in collaboration with the provincial government and includes an analysis of provincial regulations, which may already apply of general application. Only regulations that do not already apply will be included under FNCIDA.

It is important to note that FNCIDA is project specific and is initiated by First Nations who show interest in undertaking a particular large-scale commercial or industrial development on-reserve. As such, it may not be used for the incorporation of regulations by reference in the absence of a planned complex project. Specific parcels of reserve lands must be identified as part of the FNCIDA process, meaning that the Act may not be used for blanket incorporation by reference of provincial regulations onto reserve.

FNCIDA does not create uncertainty as to the status of the land

No legal uncertainty remains as a result of the application of FNCIDA regulations. Under FNCIDA, lands continue to be reserve lands.

FNCIDA provides options outside of the modern treaty process that promotes economic development and self-sufficiency

FNCIDA is a complementary tool to the modern treaty process by allowing First Nations to obtain more immediate and tangible benefits from economic development rather than waiting until the modern treaty is concluded.

A recent evaluation of the process for negotiating modern treatiesFootnote 9 found that modern treaties are arguably not capable of achieving the same certainty and finality that government initially anticipated as there is now a very complex and shifting legal and constitutional framework. Canada acknowledges that not all First Nations in Canada wish to pursue modern treaty negotiations and has developed other tools to assist First Nations to better manage their lands and resources and pursue economic and community development. Increasing options for development of reserve lands, such as the First Nations Land Management Act and the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act provide additional economic opportunities for some First Nations.

This suite of legislation options are complementary in that a First Nation under the First Nations Land Management Act could also make use of FNCIDA to pursue large scale commercial or industrial operations, without affecting a First Nation's ability to pursue modern treaty negotiations.

4. Effectiveness - FNCIDA

The evaluation looked for evidence that FNCIDA is meeting its intended results of creating opportunities for economic development projects that will generate prosperity for First Nations and create certainty about the regulatory environment for developing major commercial or industrial projects on-reserve. FNCIDA also provides the regulatory certainty for complex activities that have the potential for major impacts on the environment or health or safety. Findings from the evaluation conclude that FNCIDA has the potential for creating opportunities for economic development projects, which have the possibility of generating large revenues for First Nations through increased investment, employment and business opportunities on-reserve. While some early success has been demonstrated, complex economic development projects, like those undertaken through FNCIDA, will require a significant amount of time before they can fully demonstrate results.

4.1 Achievement of Intended Result

4.1.1 FNCIDA Process

The FNCIDA process involves a number of distinct steps. These include:

Step One – Project Identification and Proposal – During this stage the proposed development is explored to determine the conditions and necessary requirements, contractual arrangements and early identification that a regulatory gap is present. A written proposal containing project information is submitted to AANDC for consideration. This stage will normally involve initial discussions with regional AANDC staff and other stakeholders. The proposal requires a Band Council Resolution supporting the initiative.

Step Two – Project Review and Selection – During this stage, AANDC reviews the proposal. This review process takes place at two levels. At the regional level, there is a legal and cost-benefit assessment. At the national level, there is an assessment of regulatory need, an assessment of the feasibility of FNCIDA in the context of the project, its potential for economic impact, an assessment of the level of community support for the proposed project, and indication that the province has expressed interest to participate.

Step Three – Negotiation and Drafting – During this stage, a work plan is prepared outlining the necessary activities to be undertaken in order to negotiate and sign a tripartite agreement. The tripartite agreement involves the federal government, the province, and the First Nation applying to the FNCIDA program. After this, the Minister recommends to Cabinet to consider the necessary regulations for approval.

Step Four – Administration, Monitoring and Enforcement – During this stage, the economic development project is underway and the provincial government enforces the agreed-upon regulations. If and when the project concludes, facilities are eventually decommissioned and land reclamation for the reserve takes place.

To date, only one FNCIDA project has entered the fourth step (Fort William project). Much of FNCIDA's work to date has therefore focused on the first three steps with particular effort on the part of AANDC during steps two and three.

Step two in the FNCIDA process is particularly important because it is at this point that the Department conducts an assessment of the proposed project to determine whether it supports the development of regulations. What this implies is that the success of any project operating within the FNCIDA approach rests not only on the financial viability of the project, the willingness of the First Nation, its private partner, and the province to fulfill their respective responsibilities under the agreement, but also the approval of the federal government.

A number of factors are taken into consideration during this approval process. AANDC normally assesses the proposal to ensure that:

- The proposal is advanced through a Band Council Resolution requesting the use of FNCIDA.

- There are no existing sectoral or self-government arrangements that could be used to regulate the work.

- Consulting members of the First Nation (and possibly conducting a designation vote).

- The project needs require that the federal government issue land tenure.

- There are in fact regulatory gaps to address with regards to the project.

- FNCIDA addresses the regulatory gaps better than alternatives and that the project meets a cost-benefit test.

- The project has written confirmation from the province as to its willingness to participate in the process.

4.1.2 Comparison of FNCIDA Process to Off-Reserve Process

Although perhaps not immediately apparent, many of the factors, listed above, fundamentally change the nature of an industrial project operating under FNCIDA from that of one occurring off-reserve. Two of these above factors point to political involvement and a level of community support not otherwise required in most business endeavors. Factor 1 requires that a project not only be financially viable but that there is a majority belief on the part of the Band Council that it should proceed, and that FNCIDA is the most appropriate tool to facilitate the project. Factor 3 points to the fact that there must be consensus, at least among a majority of community members, regarding the nature and benefit of the project itself.

These factors are viewed positively in the evaluation, as they are done in order to ensure that the community supports an approach which will draw in provincial standards and systems, including access to the lands by provincial officials for monitoring and enforcement.

Given that proponent First Nations and their development partners will have likely assessed the financial viability of a project prior to presenting a proposal under FNCIDA, factor 6 suggests that cost-benefit is assessed from the federal government's perspective and will consider additional information. In fact, program documentation points to the fact that the federal government's cost-benefit assessment should look into benefits such as direct and indirect economic benefits to the First Nation, economic and tax benefits to the province and Canada, support of self-reliant communities, and potential applicability of regulations for other First Nations.

Program documents note that the cost-benefit analysis should consider the cost of developing regulations for all parties, provincial costs of administering regulations, as well as potential exposure to liability for Canada and the First Nation. Many of these are not considerations for businesses operating in an off-reserve context.

Step three in the FNCIDA process, negotiation and drafting, also bears mention. AANDC acknowledges that the negotiation and drafting stage requires a considerable amount of time and effort by not only the Department, but also the provincial government, the proponent First Nation, and the private partner. For example, development of the Squamish Nation's FNCIDA regulations required two to three years of effort and the review of over 500,000 pages of law. It is important to understand that this time is added to the time and effort on the part of the proponent First Nation and its private partner to first develop a viable project plan.

The extra resources and time required to develop a regulatory regime for a FNCIDA project compared to a similar project off-reserve means that the success of a FNCIDA project requires a relatively strong infrastructure on the part of the participating First Nation. This includes the ability of the leadership of the community to fully engage and sustain the collaboration and negotiations associated with the project over an extended period of time. In other words, the community must be operating in a fairly stable political, social, and economic environment. It is acknowledged that a limited number of First Nations will actually have access to the types of resources that can lead to a significant commercial or industrial project requiring a FNCIDA regulation. It was noted that these types of projects are expected to emerge in central and western Canada predominantly.

4.1.3 Status of FNCIDA Projects

There are currently five FNCIDA projects that have been undertaken.

Fort William First Nation – Ontario - Wood Fibre Optimization Plant

- Status: Enacted Regulations. Project proceeded and achieving expected results. The sawmill is fully operational with a regulatory framework in place.

- The project was a collaborative venture between Fort William First Nation and Resolute Forest Products.

- Sawmill operations began in May 2003 and regulations pertaining to the sawmill operation under FNCIDA came into effect in June 2011.

- The sawmill operation provided the expected financial benefit to Fort William First Nation.

- Members of the First Nation are the first ones to find out about employment opportunities. This has resulted in the mill having 17 percent First Nation employment.

- The sawmill has expanded operations and the province has not faced any challenges in executing its enforcement duties. Sawmill remains in operation while other sawmills in the region are closing.

Muskowekwan First Nation - Saskatchewan – Potash Mine

- Status: In progress – The formal proposal has been approved, the project is in the early stages - at the time of the evaluation, all parties were collaborating to move forward with the project.

- Key milestones to be undertaken:

- The regulatory framework must be adopted by the federal government in order to incorporate by reference the appropriate laws and regulations.

- The tripartite agreement must be signed.

- The parties have yet to secure the capital investment required to proceed with the building of the mine.

- Mining project related to potash production and export proposed by a joint venture agreement between the Muskowekwan Resources Ltd (wholly-band owned company), and Encanto Resources Ltd (operating as First Potash Ventures). The proponents are continuing to secure capital investment for this project.

- Without firm assurance as to regulatory certainty, it is unlikely that the partners would invest the significant amount of funds required (estimated at $2 billion) for a potash operation. Benefits to the community will include significant royalty revenues, training and employment, and other benefits.

- FNCIDA provides assurances to the community that the potential substantial environmental impact and health and safety risks of the project are being adequately monitored and managed.

Squamish First Nation – British Columbia – Commercial Real Estate

- Status: In progress – Drafting instructions for the regulations is being reviewed by the Department of Justice and the Tripartite Agreement is finalized.

- The project has been delayed because of the changing conditions in the Vancouver real estate market as well as elections in the community. Discussions within the community are ongoing and AANDC is ready to proceed when the community is ready.

- The project is expected to result in 12,000 to 15,000 condominium units with an estimated value of $10 billion.

- Work to apply FNCIDA began in 2008. The FNCIDA Implementation Act was passed in 2012 by the Government of British Columbia to facilitate the project. It paves the way for provincial land title regulations to be enforced on-reserve.

- FNCIDA was essential for the development of this project as there is no federal regulatory regime governing condominium development. FNCIDA thus harmonizes requirements with the rest of the province and increases certainty for the public and investors.

- The project is considered a success, given that the technical aspect of the work has been completed and negotiations have been completed.

Fort McKay First Nation – Alberta - Oil Sand Mining

- Status: Enacted regulations-Project did not proceed because of a downturn in the economy and a change in the commercial arrangements of the private sector partner. Regulations were enacted and intergovernmental tripartite agreement with all relevant parties was put in place.

- A cost-benefit analysis found that over a 25 year period, the economic benefit would be between $1 - 2.3 billion to Fort McKay First Nation and $360 - 720 million in federal tax revenue. A further $3.3. – 6.6 billion in direct and indirect benefits to Canada as a whole were also anticipated to be realized. Meanwhile the cost of developing the regulations and agreement were estimated at $1.7 million.

- Although the project did not proceed, Fort McKay First Nation was the first proposed FNCIDA project in Canada and the first to successfully negotiate and pass supporting legislation. It would have been the first Aboriginal community to join the oil sands business as a producer through a partnership with Shell Canada Ltd.

- The FNCIDA regulatory regime was critical for the project. Considering the risks to all parties in the absence of a regulatory framework, the project could not have proceeded absent a federal regulatory regime.

- According to key informant interviews, the project was dropped following the purchase of Shell Canada by Royal Dutch Shell. Fort McKay First Nation could not agree with the Project Proponent on a commercial arrangement.

- A second set of regulations may be produced to update the initial framework as required.

Haisla First Nation – British Columbia - Liquefied Natural Gas Plant

- Status: Enacted regulations. -– First Nation currently in negotiations with investors.

- The project is a strategic priority for all parties involved. It is expected to generate 500 jobs during construction, over 100 permanent jobs for ongoing operation, and a significant amount of revenue for the First Nations. The project is also expected to generate hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue for the federal government.

- The Government of British Columbia has passed legislation to facilitate FNCIDA regulations. The regulatory regime was completed in 2012.

- A tripartite agreement has been established regarding the procedures for administration, monitoring and enforcement of the proposed regulations

- Negotiations are continuing with investors. Original proponent just sold interests.

- British Columbia stake in the natural gas industry is growing.

4.2 Unexpected Impacts

A number of unexpected, or at least not directly anticipated, impacts of FNCIDA were noted. The one that was raised by a number of key informants related to the positive relationships that are being built through the FNCIDA process. For instance, the negotiations leading up to a tripartite agreement provide an opportunity for the participating First Nation to establish closer relationship with provincial authorities. The same goes for provincial ministries that may have had limited opportunities to collaborate with First Nations. As more FNCIDA projects move forward, it is anticipated that the private sector may also increase its awareness of economic opportunities that may be explored with First Nations.

Another unexpected impact was that providing these opportunities under FNCIDA may prevent litigation from First Nations based on the concept of lost opportunities as it is the Indian Act that has created the regulatory gap that FNCIDA is now attempting to address. In the absence of FNCIDA, key informants noted that the existing legislative tools are simply not providing the appropriate framework for large scale commercial and industrial projects to move forward.

Over the last six fiscal years (2008-2014), the annual average funding allocated to FNCIDA in the Main Estimates was $2.6 million compared to the annual average actual expenses of $.424 million. The program explained that some of this difference is due to costs associated with legal services incurred by the regions and Headquarter and also draft costs that are not included in the total actuals. See Section 1.2.4 – Program Resources for details of FNCIDA funding.

5. Efficiency and Economy - FNCIDA

The evaluation examined whether FNCIDA is the most appropriate and efficient means to achieve outcomes, relative to alternative design and delivery approaches. The evaluation concludes that FNCIDA remains the best approach to address regulatory gaps on-reserve. In order to harmonize laws applicable to commercial and industrial projects on reserve lands with those applicable on provincial lands, the regulations require a high level of control and accountability. Details regarding enforcement issues and responsibilities of each party need to be negotiated and pre-determined prior to project implementation. FNCIDA, through its system of regulations and tripartite agreements, provides this level of assurance.

There was an underestimated level of effort and resources required as preparing the regulation and negotiating the tripartite agreement for some projects is requiring a significantly longer time period than initially anticipated. Although some efficiencies have been implemented to counter this, including the development of templates for standardizing elements of the tripartite agreements, there are areas in which further efficiencies can be realized. It is important to note that the work put in to create a regulatory regime under FNCIDA, while being limited in application to the project lands, can be adapted to apply to similar projects within the same province. In a similar vein, the negotiation of tripartite agreements is expected to become less onerous once a province has participated in the process once before. In addition, the preparation and drafting of regulations can be adapted to facilitate similar First Nations projects in the future.

5.1 Key Factors that Facilitate Efficiency and Economy

The negotiation process leading up to a tripartite agreement can be fairly lengthy. As a result, it is critical to maintain a high level of involvement and engagement in the process from all key stakeholders. The process can be resource intensive for all parties.

Timing is a critical factor in the success of any FNCIDA project. In addition to the time required to complete all steps related to the FNCIDA regulations and the negotiation of the tripartite agreement, it must be anticipated that the actual implementation of projects of that magnitude will require a significant time period during which economic conditions may evolve in favor or not of the project. The example of Fort McKay has been noted as a clear illustration that the fruition of any FNCIDA project cannot be guaranteed and that many factors external to the participating parties can significantly affect the achievement of the expected results. Completion of FNCIDA projects may be prone to delays due to political and economic reasons. Moreover, the regulatory regime is only one of many components in a complex undertaking, and delays due to external factors sometimes cannot be avoided as would be reasonably expected for similar projects located off the reserve.

There must be a clear incentive for the province to participate in the process. All key informants who have been involved in a tripartite negotiation process have noted that a lot of explanation and convincing must be anticipated at the beginning of the process. Indeed, provincial authorities typically raise a number of questions regarding the extent of their obligations and, more importantly, the extent of their liability as they exercise their functions of enforcement on behalf of the federal government. Also, the province is required to dedicate a fair amount of resources in the initial stage while the negotiation of the agreement is taking place with no financial support being provided. Having said this, many key informants noted that the costs to the province for participating can be off-set by the many benefits they would receive as a result of a successful project. Provincial authorities may receive benefits from FNCIDA projects in the form of new revenues, new employment, and a consistent regulatory framework being applied in the entire province.

Given the scale of the projects allowable under FNCIDA, a relatively high level of management expertise on the part of participating First Nations would seem to be a prerequisite. Since FNCIDA also explicitly links political and economic development decision making through the requirement for a Band Council Resolution and a community referendum on projects, it would seem that the program implicitly requires an established system of good governance.

5.2 Alternatives

Although FNCIDA is one tool available to address regulatory gaps on-reserve and support economic development activities, a number of additional options are also available to First Nations communities. These approaches include the followingFootnote 10.

- Operating without regulations – This approach is normally proposed for very small scale projects that often do not require off-reserve investment or support. It can be found where there is no expectation of regulation on-reserve or where there is already a provincial mandate to regulate on-reserve.

- Regulation through contract –In this case, the adherence to regulations is identified in the contract between the First Nation and the private partner involved in the project. One of the challenges with this arrangement involves a lack of a regulatory authority to monitor and enforce the regulatory provisions of the contract – this is often left to the First Nation. In addition, the main recourse for violations of regulatory provisions involves breaking the contract. This may have negative implications for both the First Nation and the private partner. Finally, the pursuit of damages following violations of the regulatory provisions must involve litigation, unless a bond or similar type of security is provided upon signing of the contract.

Under the regulation through contract option, it is also important to distinguish between two types of contracts when leasing land. The first involves a lease agreement between an individual band member or a First Nation, and another individual or business, which is also approved and registered with the federal government. The second, often referred to as a buckshee lease, involves an individual band member or a First Nation and another individual or business. It is not approved by the federal government or registered in the Indian Land Registry, and as a result, is not enforceable. - Indian Act regulations – In some instances, federal regulations may be applicable on-reserve. For example, Indian mining regulations do exist and could be applied to the FNCIDA potash mining project. The difficulty is that federal regulations governing activities on-reserve often fall short of what is needed in today's economy. That is, these regulations are bound by the provisions of the Indian Act, which do not provide the necessary guidance for services, administration, fines or penalties. Often federal regulations have not evolved in as sophisticated a manner as required in the off-reserve context and applying these regulations would create difficulties for enforcement and monitoring officials, especially if provincial agents are to be used through contract.

In other instances, there is the possibility of developing new regulations under the Indian Act, however, these would be applicable across the country and not to a particular project within a particular province's jurisdiction resulting in a disharmony between the on- and off-reserve regulatory environments. This type of regulatory development is challenging for a number of reasons, not least of which involved their national scope and the lack of enforcement capacity at the federal level. - First Nations regulations – In this case, First Nations would enact their own regulatory requirements and enforce these on-reserve. However, as AANDC notes, there's some uncertainty on the part of the federal government as to whether there is the authority for this type of regulation among communities under the Indian Act. In addition, the federal government would continue to be exposed to risk and liability associated with type of arrangement. It is important to note that this uncertainty would not exist among First Nations under the First Nations Land Management Regime.

- Tool of broader application – It has been suggested that FNCIDA could be made into a tool of broader application by amending the Act to include all the adaptations into the FNCIDA Act directly. For example, any reference to provincial Crown agenda shall be referred to as federal agent, and any provincial regulation referred to in the Act will apply. This approach, however, would not necessarily obtain the intended results of reducing negotiation and regulatory development times. As the regulatory regime varies widely from province to province and between industries, it is best to use a more flexible approach, such as templates and commonly used adaptation definitions, to streamline the FNCIDA process without being overly prescriptive.

While each of these approaches differ, and have associated strengths and weaknesses, the evaluation concludes that, at this time, FNCIDA remains the best approach to address regulatory gaps on-reserve as the alternatives would not provide sufficient avenues to ensure the enforcement of all the applicable regulatory requirements. FNCIDA is a unique legislative tool that responds to First Nation, provincial, and investor demands for regulatory certainty. To achieve this requires a degree of unique tailoring to suit the needs of the project. Overall, FNCIDA provides a balance approach to addressing regulatory gaps that is accepted by First Nations.

5.3 Lessons Learned

The evaluation identified a number of lessons learned.

5.3.1 General

- All parties need to remain flexible during the entire process as adjustments are to be expected because of the nature of undertaking complicated economic projects.

- Build and maintain expertise within the federal team (AANDC regional office, Headquarters and Justice Canada). Regional representatives must be familiar enough with the various potential use of this tool, even if they do not have all the technical knowledge related to each of the steps involved in the process.

- As more regulations and more tripartite agreements are being signed, there will be further opportunity to refine the templates and reduce the amount of work and time required during drafting and negotiations.

5.3.2 Project Specific

Muskowekwan First Nation - Saskatchewan – Potash Mine

- Implementing this large scale project has been successful to date due to the strong and stable leadership in the First Nation community. The close relationship built with other stakeholders must be maintained.

- While FNCIDA is a key component of the project, there are a multitude of other dimensions associated with these types of complex projects that the First Nation must be in a position to manage.

- The First Nation community must be well informed about the strengths and the potential risks associated with the project. A clear line of communication, though difficult, must be maintained particularly in light of the high stakes related to a project of this magnitude.

- Engaging the provincial authority as early as possible in the process is critical, as they are party to the tripartite agreement and would often be looked upon to play a significant role in the success of such projects.

Fort William First Nation – Ontario - Wood Fibre Optimization Plant

- The parties had already established effective relationships, which proved beneficial during the negotiation phase.

- The Province of Ontario was committed to supporting this economic initiative.

- AANDC regional office had a strong knowledge of FNCIDA and of the project, which facilitated the development of the regulations and tripartite agreement.

5.4 Performance Measurement

The Lands and Economic Development Sector is implementing the Performance Measurement Strategy for Investment in Economic Opportunities dated March 2014. As the FNCIDA projects proceed, the sector will revisit results and indicators. There is recognition that the success of projects after the enactment of regulations is out of the control of AANDC.

Section Two: Community Economic Opportunities Program

6. Relevance - CEOP

The evaluation looked for evidence that CEOP addresses an actual need, is aligned with government priorities and is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities. Findings from the evaluation point to the evaluation issue of relevance being positively demonstrated as CEOP addresses many barriers faced by First Nation and Inuit communities when pursuing economic development. CEOP aligns with the federal government priorities as articulated in the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and falls within the jurisdictional scope of the federal government.

6.1 Ongoing Need for CEOP

CEOP projects address many barriers faced by First Nation and Inuit communities when pursuing economic development

CEOP projects support economic infrastructure, skills and human development, governance, community and economic development plans and accessing capital. CEOP provides funding support to First Nations and Inuit communities who are positioned to undertake greater utilization of their lands and resources, enhance community economic infrastructure, and enhance capacity to address future economic opportunities for economic development purposes.

Findings from the evaluation point to the ongoing need in First Nation and Inuit communities for access to capital, technical support, business and management expertise that contributes to increased capacity and infrastructure in support of economic development projects.

Economic development support is tied to expansion of reserve land

The Additions to Reserve processes and land designation are opening up new economic opportunities. Since 2006, nearly 350,000 hectares of land were added to reserves under the federal Additions to Reserves / New Reserves Policy, a 12 percent increase to the First Nations land base.

There is a demonstrated need for economic development in Aboriginal communities as identified through key indicators of economic development

Along many dimensions of economic development, such as employment rate, labour force participation and income, First Nation and Inuit communities lag behind the rest of Canadians. Access to wealth for First Nation and Inuit communities is viewed as an essential condition for effectively dealing with social challenges that are triggered by poverty and unemployment. See Appendix B for detailed analysis or economic development indicators for Aboriginal people.

6.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities

Various Government of Canada commitments have supported Aboriginal economic development as a government priority. The 2012 Crown-First Nations Gathering committed to unlocking the economic potential of First Nations as a priority. Federal budgets 2012, 2013, and 2014 have noted a commitment to Aboriginal economic development. CEOP also plays a role, another key priority of the federal government.

CEOP is aligned with the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development by providing opportunities for First Nation and Inuit communities for skills development and leveraging investment and promoting partnership with the private sector. CEOP supports opportunity-ready First Nation and Inuit communities to attract business and investors.

6.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

CEOP supports economic policy objectives. The Indian Act does not explicitly obligate the federal government to invest federal money towards Aboriginal economic development. Economic development is therefore not a legal obligation under the Indian Act, but rather a policy approach to help address major socio-economic discrepancies between First Nations and Inuit as compared to non-Aboriginal people.

7. Effectiveness - CEOP

The evaluation looked for evidence that CEOP is meeting its intended results of First Nation and Inuit communities implementing strategic economic and business development opportunities. Findings from the evaluation conclude that CEOP has funded a wide range of projects, which have demonstrated positive results, including increase in employment of community members, community business development, and development of lands and resources. Resource allocation has emerged as an issue with 57 percent of allocated funding through the Main Estimates for CEOP not being spent as reflected in the actuals, though program officials within Lands and Economic Development Sector state that demand for CEOP projects exceeds available allocated funding.

7.1 Achievement of Intended Results

7.1.1 CEOP Projects Undertaken

Between 2009 and 2013, 882 CEOP projects were undertaken supporting over 292 First Nations and Inuit Communities, with a funding total of over $83 million. During this period, CEOP funded a wide range of initiatives.

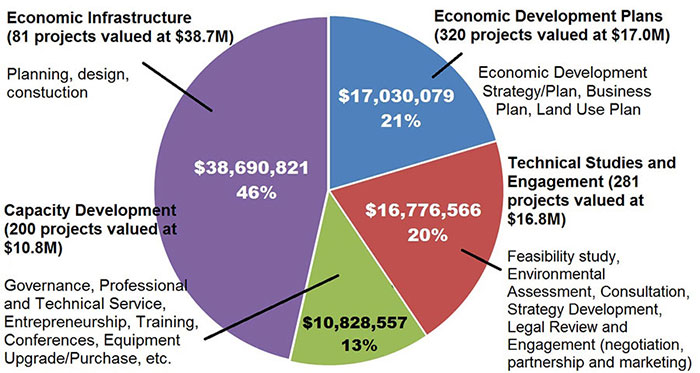

Text alternative for CEOP Projects Undertaken

The image is in the form of a pie chart and demonstrates the amount of money allocated to the four different types of CEOP projects between 2009 and 2013.

The largest portion of money was allocated to "Economic Infrastructure", totaling 81 projects that were valued at $38,690,821. This project category included specific activities, including planning, design and construction. This section of the pie chart is purple and the funding for this project category represents 46% of over $83 million that CEOP used to support these initiatives.

The second largest category is "Economic Development Plans", totaling 320 projects that were valued at $17,030,079. This project category included specific activities, including developing economic development strategies and plans, business plans, and land use plans. This portion of the pie chart is blue and represents 21% of the total funding.

The third largest category is "Technical Studies and Engagement", totaling 281 projects that were valued at $16,776,566. This project category included specific activities, including feasibility studies, environmental assessment, consultation, strategy development, legal review and engagement (negotiation, partnership and marketing). This portion of the pie chart is red and represents 20% of the total funding.

The fourth category is "Capacity Development", totaling 200 projects that were valued at $10,828,557. This project category included specific activities, including governance, professional and technical service, entrepreneurship, training, conferences, equipment upgrade and purchase, etc. This portion of the pie chart is green and represents 13% of the total funding.

7.1.2 CEOP Project Results

CEOP is a well-constructed and flexible proposal based program that responds to community imperatives and covers a variety of economic priorities and opportunities. CEOP provides the opportunity for First Nation and Inuit communities to design and implement strategies designed to address a market gap.

| First Nation | Region | CEOP ProjectsFootnote 11 | Results | Why Best Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stz'uminus First Nation | British Columbia | Infrastructure land use planning projects Five CEOP projects – total value of $3.3M |

|

|

| Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation | Alberta | Development of reserve lands through land use plan implementation Four CEOP projects – total value of $3.2M |

|

|

| Flying Dust First Nation | Saskatchewan | Commercial and corporate development projects Nine CEOP projects – total value of $.5M |

|

|

| Opaskwayak Cree Nation | Manitoba | Mining, training, hospitality and website projects Seven CEOP projects – total value of $.2M |

|

|

| Nipissing First Nation | Ontario | Commercial housing and small business projects Three projects – total value of $.235M |

|

|

| Conseil Des Montagnais Du Lac St-Jean | Quebec | Industrial and manufacturing projects 11 CEOP projects – total value of $2.8M |

|

|

| Membertou | Atlantic | Commercial and business development 15 CEOP projects – total value at $3.5M |

|

|

Positive impacts also demonstrated through the case studies that were randomly selected