Evaluation of the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program

June 2015

Project Number: 1570-7/14091

PDF Version (1,412 KB,99 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A – Complimentary Government Programs and Opportunities for Leveraging other Funding for Improved Results

- Appendix B: Related Academic/Research Activities

- Appendix C: Costs and Benefits of Renewable Energy Technologies

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| CHARS |

Canadian High Arctic Research Station |

| CIB |

Community Infrastructure Branch, AANDC |

| EPMRB |

Evaluations, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| EPMRC |

Evaluations, Performance Measurement and Review Committee |

| GHG |

Greenhouse Gas |

| kW |

Kilowatt |

| Mt |

Megatonne |

| mW |

Megawatt |

Executive Summary

This evaluation of the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program (hereafter referred to as ecoENERGY) was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation and in time for consideration of program renewal in 2014-15. The evaluation expands upon the program's 2010 impact evaluation, and examines ecoENERGY's relevance (continued need), and program performance (effectiveness, economy and program design and delivery), from April 2011 to December 2014. The evaluation was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC).

The ecoENERGY program was renewed in 2011, and received $20 million over five years (2011-12 to 2015-16). It supports Aboriginal and northern communities in their attempt to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by funding the integration of proven renewable energy technologies such as residual heat recovery, biomass, geothermal, wind, solar and small hydro. The program provides two streams of funding support, including:

- Stream A: Funding to support feasibility studies of larger renewable energy projects (up to $250,000 funding for projects that result in greater than 4000 tonnes of GHG reductions over the projects' lifecycle).

- Stream B: Funding to support the design and construction of renewable energy projects integrated with new and existing community buildings (up to $100,000 per project).

The evaluation generated 19 findings, six recommendations for program management, and four considerations for AANDC's Senior Management Team as represented by members of the Operations Committee:

Program Need

Finding 1: There is a continued need for the Government of Canada to reduce GHG emissions.

Finding 2: There is a continued need to fund renewable energy and energy efficient projects in Aboriginal and northern communities that: 1) replace diesel systems; 2) off-set high energy costs; and 3) support economic development.

Finding 3: International examples demonstrate that there is a continued need for an ecoENERGY program that focuses on off-grid and northern communities.

Alignment with Roles and Responsibilities:

Finding 4: The ecoENERGY program is aligned with roles and responsibilities of the federal government, and specifically, the mandate of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

Recommendation 1: It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program clearly define its niche, focusing on funding renewable energy projects in off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities.

Recommendation 2: It is recommended that as ecoENERGY establishes a focus on off-grid and northern communities, program staff should provide lessons learned, best practices and relevant Stream A project proposals to Lands and Economic Development Sector (i.e., Community Opportunity Readiness Program), which already funds such projects. Program staff should also communicate their change in focus to communities and provide information concerning potential Lands and Economic Development funding opportunities.

Alignment with Federal, Departmental and Community Objectives:

Finding 5: The ecoENERGY program is aligned with federal priorities, AANDC's priorities and the needs and priorities of Aboriginal and northern communities.

Program Effectiveness:

Finding 6: ecoENERGY is delivering on its expected results of developing and constructing viable renewable energy projects.

Finding 7: ecoENERGY is delivering on its expected result of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Aboriginal and northern communities.

Finding 8: ecoENERGY is delivering on its expected result that communities have a base of infrastructure that protects the health and safety and enables engagement in the economy.

Finding 9: Proposal-based design encourages a vendor-driven funding model instead of targeting communities with the greatest needs.

Finding 10: Although some work to align ecoENERGY with existing AANDC, Natural Resources Canada and Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency programming is occurring, there is a need for partners to better coordinate their renewable energy investments and support provided to off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities.

Finding 11: The Headquarters centralized program delivery approach could be improved by coordinating the development and implementation of targeted projects with regional staff in the Community Infrastructure Branch.

Finding 12: Streams A and B provided funding for necessary studies and projects; however, opportunities exist to move away from rigid funding categories to funding the right stage on the renewable energy development continuum that promotes the movement from studies to tangible infrastructure.

Finding 13: Opportunities exist to increase communities' knowledge, capacity and confidence to undertake projects by promoting knowledge-sharing initiatives and mentorships.

Recommendation 3: It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program consider the following in any future program re-design:

- Review the effectiveness and desirability of maintaining separate funding streams and maximum project allotments.

- Review the effectiveness and desirability of the proposal based approach.

- Develop an approach for targeting communities with the greatest need.

- Support projects that integrate renewable energy systems into existing diesel systems to reduce the consumption of diesel fuel.

- Provide active and appropriate support to communities in their assessment and advancement of potential renewable energy and/ or efficiency projects.

Recommendation 4: It is recommended that ecoENERGY establish a process for developing an Engagement and Collaboration Strategy for each off-grid community it targets, ensuring that activities and investments by AANDC, federal partners (e.g., Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, Natural Resources Canada, Canadian High Arctic Research Station (CHARS) and other levels of government, are coordinated to allow for communities to seamlessly go from research, to pilot project, to final, completed project.

Recommendation 5: It is recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister of Northern Affairs work with the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of Regional Operations to improve coordination of funding renewable energy projects in Aboriginal communities occurring within the Community Infrastructure Branch and the ecoENERGY program.

Considerations for Operations Committee 1: The Department, in partnership with federal partners (e.g., Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, Natural Resources Canada, CHARS) and other levels of government, explore developing a central five year tracking system to identify activities and investments in all off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities to increase strategic collaboration.

Considerations for Operations Committee 2: The Department explore developing a departmental Sustainable Energy Policy that:

- Supports the design, construction and implementation of renewable energy systems that supply energy to communities within AANDC's mandate; and

- Promotes the funding of small-scale infrastructure projects that increase energy efficiency in order to decrease energy demand (i.e. replacing windows, boiler systems, insulation, etc.)

Considerations for Operations Committee 3: The Department explore developing a system for tracking and organizing funded community planning documents and feasibility studies (e.g. Energy Audits, Infrastructure Plans, Emergency Management Plans, Climate Change Adaptation studies, Comprehensive Community Plans, etc.) in order to better preserve funded work and support future infrastructure development decisions. AANDC's Strategic Research Branch may be in a position to develop such a centralized database as one of their departmental research tools.

Program Efficiency:

Finding 14: Internal project approval process results in funding often being provided during inappropriate construction seasons.

Finding 15: There is an opportunity for the ecoENERGY program to improve its Performance Measurement Strategy to track program efficiency and to more efficiently track all AANDC renewable energy projects.

Finding 16: Potential risk of projects not achieving their full GHG reduction potential when communities do not have an operation and maintenance plan in place for completed renewable energy projects.

Recommendation 6: It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program update its Performance Measurement Strategy and Risk Assessment to reflect program re-design considerations and to determine an approach for monitoring the completion of renewable energy projects funded across the Department.

Program Economy - Cost Benefit:

Finding 17: The proportion of program funding dedicated to salary and operation and maintenance costs are in large measure due to the technical reviews and expertise required to assess project proposals as well as the necessity to coordinate funding with other federal, provincial and territorial departments.

Finding 18: While large renewable energy systems can have dramatic environmental and financial benefits for communities, in off-grid scenarios diesel energy generation often remains the most cost-effective approach.

Finding 19: Projects that incorporate renewable technology into new construction projects are more cost effective than replacing older systems.

Considerations for Operations Committee 4: The Department explores pursuing partnerships with provincial utilities to develop a supportive environment for the growth of the renewable energy industry in off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program

Project #: 1570-7/14091

1. Management Response

This Management Response and Action Plan has been developed to address recommendations resulting from the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program evaluation, which was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch. The program is entering its fifth and final year of operation (2015-2016). The timing of this evaluation is well aligned to inform the development of related future programming under consideration for implementation beyond the March 2016 program sunset date.

Overall, the evaluation was positive and confirmed the ecoENERGY program's continued relevance, effectiveness, and value. Specifically, the program is:

- Aligned with roles and responsibilities of the federal government, the mandate and priorities of AANDC, and the needs and priorities of Aboriginal and northern communities;

- Delivering on its expected results of developing and constructing viable renewable energy projects and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Aboriginal and northern communities; and

- Fulfilling a demonstrated continued need to fund renewable energy and energy efficient projects in Aboriginal and northern communities.

The evaluation provided six recommendations to improve the design and delivery of a future program. All recommendations are accepted by the program and the attached Action Plan identifies specific activities by which to address these.

The first recommendation speaks to refocusing funding support solely for projects in off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities (i.e., communities facing the greatest energy challenges as a result of their diesel dependence). For project funding in 2015-16, priority has already been accorded to projects in northern communities (in the territories) and projects in off-grid communities (those not connected to a provincial or regional electrical grid).

This shift in focus signifies that the program, if renewed, would no longer be available to support renewable energy projects in First Nation communities south of 60 that are grid-connected. As a result, and as discussed under the second recommendation, the program will work with the Lands and Economic Development Sector to transfer knowledge with respect to past, ongoing, and potential future renewable energy projects in grid-connected communities south of 60.

Similarly, the program will also continue work with the Regional Operations Sector and the Lands and Economic Development Sector to maintain awareness and increase coordination, and to maximize results in all investments, should the program be renewed.

Other recommendations speak further to broader collaboration outside of AANDC and to operational program improvements, including strengthening support for targeted communities. These recommendations are being considered for integration into proposed future programming.

Actions to address the recommendations will continue over the next 12-18 months although at this time, a decision on any future programming is still pending. The timeline for program renewal is unclear and may impact on the planned implementation and completion dates identified in the table below. Where necessary, the program has set aside resources to deliver on the identified action items.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program clearly define its niche, focusing on funding renewable energy projects in off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities. | The program accepts this recommendation. a) The program has identified targeting projects in off-grid and northern communities as the focus of any future funding program. |

Director – Environment and Renewable Resources, Northern Affairs Organization |

a) Completed for 2015-16. Priority for funding has been accorded to projects in northern and off-grid communities. In-progress for future programming – decision pending. |

2. It is recommended that as ecoENERGY establishes a focus on off-grid and northern communities, program staff should provide lessons learned, best practices and relevant Stream A project proposals to the Land and Economic Development Sector (i.e., Community Opportunity Readiness Program), which already funds such projects. Program staff should also communicate their change in focus to communities and provide information concerning potential Land and Economic Development funding opportunities. |

The program accepts this recommendation. a) For 2015-16 projects, a member of the Community Opportunity Readiness Program has participated on the ecoENERGY Project Review Committee. b) Over a transition period, the program will meet with and share past and current proposals and project information for renewable energy projects in on-grid communities, as well as available technology information, with the Community Opportunity Readiness Program. c) The program will work with Communications and with the Lands and Economic Development Sector to develop appropriate materials to share with communities on ongoing or new funding opportunities. |

Director – Environment and Renewable Resources, Northern Affairs Organization |

a) Completed April/May 2015. b) and c) Completed by December 2016, assuming program renewal implementation in April 2016. |

3. It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program consider the following in any future program re-design: a) Review the effectiveness and desirability of maintaining separate funding streams and maximum project allotments. b) Review the effectiveness and desirability of the proposal based approach. c) Develop an approach for targeting communities with the greatest need. d) Support projects that integrate renewable energy systems into existing diesel systems to reduce the consumption of diesel fuel. e) Provide active and appropriate support to communities in their assessment and advancement of potential renewable energy and/ or efficiency projects. |

The program accepts this recommendation. a) The program has considered these elements in the proposed approach for any future funding program. |

Director – Environment and Renewable Resources, Northern Affairs Organization |

a) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. |

4. It is recommended that ecoENERGY establish a process for developing an Engagement and Collaboration Strategy for each off-grid community it targets, ensuring that activities and investments by AANDC, federal partners (e.g., CanNOR, NRCan, CHARS) and other levels of government, are coordinated to allow for communities to seamlessly go from research, to pilot project, to final, completed project. |

The program accepts this recommendation. a) The program has integrated this concept into the proposed program approach for any future funding, and will work on refining specific details at a regional level throughout the development of the program Management Control Framework. b) Where necessary to ensure productive and ongoing collaboration with other federal partners and other levels of government, the program will host official meetings and/or seek to develop a formal Engagement and Collaboration Approach with key organizations. |

Director – Environment and Renewable Resources, Northern Affairs Organization |

a) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. Management Control Framework to be completed by December 2016. b) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. Meetings and formal Engagement and Collaboration Approach to be completed by December 2016. |

5. It is recommended that the ADM of the Northern Affairs Organization work with the Senior ADM of Regional Operations to improve coordination of funding renewable energy projects in Aboriginal communities occurring within the Community Infrastructure Branch and the ecoENERGY program. |

The program accepts this recommendation. a) The ADM of the Northern Affairs Organization will work with the Senior ADM of Regional Operations to ensure that any future Northern Affairs Organization energy program will align, where feasible, with existing regional and/ or headquarters processes to ensure better coordination of funding for renewable energy projects in communities to maximize investments. |

Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization | a) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. Management Control Framework to be completed by December 2016. |

6. It is recommended that the ecoENERGY program update its Performance Measurement Strategy and Risk Assessment to reflect program re-design considerations and to determine an approach for monitoring the completion of renewable energy projects funded across the Department. |

The program accepts this recommendation. a) The program has updated its Performance Measurement Strategy and Risk Assessment to reflect program redesign considerations. b)The program has established a concept for monitoring projects funded by the program which will be further refined through the development of the program Management Control Framework. c) The program will work with Regional Operations and the Lands and Economic Development Sector to determine options for tracking renewable energy projects across the Department. |

Director – Environment and Renewable Resources, Northern Affairs Organization |

a) A draft Performance Measurement Strategy was approved by EPMRC on April 24, 2015. b) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. Management Control Framework to be completed by December 2016. c) In-progress for future programming – decision pending. Options completed by December 2016. |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on June 15, 2015, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed on June 16, 2015, by:

Wayne Walsh for:

Stephen M. Van Dine

Assistant Deputy Minister of the Northern Affairs Organization

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This evaluation of the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program (hereafter referred to as ecoENERGY) was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation and in time for consideration of program renewal in 2014-15. The evaluation expands upon the program's 2010 impact evaluation, and examines ecoENERGY's relevance (continued need), and program performance (effectiveness, economy and program design and delivery), from April 2011 to December 2014. The evaluation was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC).

The ecoENERGY program was first established in 2007, building upon the pre-existing 2003-2006 Aboriginal and Northern Community Action Program. The program is operated by the Northern Affairs Organization (Sector) and is centrally run out of AANDC Headquarters, with a support network of regional staff to amend contribution agreements that allow the flow of Headquarters funding to communities with approved project proposals. The program was renewed in 2011, for five years.

At the departmental level, ecoENERGY is one of six sub-programs under AANDC's broader Infrastructure and Capacity program areaFootnote 1, which is situated within AANDC's Land and Economy Strategic Outcome area. Within the broader context of the federal government, ecoENERGY is part of the Clean Energy suite of programs, under Canada's Clean Air Agenda, led by Natural Resources Canada.

The Clean Air Agenda is a fundamental component of the Government of Canada's broader efforts to address the challenges of climate change and air pollution, in order to build a clean and healthy environment for all Canadians. The Clean Air Agenda supports eleven departments and agencies, with programming under five themes:

- Clean Air Regulatory Agenda

- Clean Energy

- Clean Transportation

- International Actions

- Adaptation

The Clean Energy Theme is a suite of seven programs aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Partner departments and agencies are responsible for evaluating their respective programs and contributing their results to a Clean Energy Thematic Evaluation led by Natural Resources Canada in fiscal year 2014-2015.

The following evaluation provides an objective and independent analysis of the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program. It also provides specific analysis of the program's current design and implementation. Evaluation findings were based on the triangulation of document and literature reviews, key informant interviews, and community case studies. The evaluation generated 19 key findings and six recommendations.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

AANDC has a long history of supporting the development of renewable energy and energy efficiency for on-reserve Aboriginal and northern communities.

The ecoENERGY program, introduced in 2007, grew out of the previous 2003-2006 Aboriginal and Northern Community Action Program. From 2007-2011, the ecoENERGY program supported over 96 communities and funded over 110 projects. Within the 110 funded projects, 41 were undertaken in remote "off-grid" communities that are not connected to a larger, region-wide grid, but rather have small micro-grids that disperse energy from a power source (usually a diesel generator) to buildings in the community. It is anticipated that the 110 projects will result in the displacement of a minimum of 1.3 megatonnes (Mt or million tonnes) of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over their 20-year lifecycle.

The 2010 Clean Energy Review, led by Natural Resources Canada, supported the continuation of the ecoENERGY program, finding that it had successfully enabled the identification of local energy resources to deliver economic and environmental benefits within Aboriginal and northern communities. The program was subsequently renewed from 2011-2016. Its primary objective was to reduce GHG emissions by over 1.5 megatonnes. The program intended to do so by supporting the development and implementation of renewable energy projects that reduced or displaced the natural gas, coal and diesel generation of electricity and heat.

The renewed program was intended to address major energy challenges for Aboriginal and northern communities, including high and fluctuating costs of energy, occasional brown-outs, aging and inefficient infrastructure, and off-grid isolated communities reliant upon emissions-intensive diesel fuel systems. To address these challenges, ecoENERGY has supported Aboriginal and northern communities in their attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by funding the integration of proven renewable energy technologies such as residual heat recovery, biomass, geothermal, wind, solar and small hydro. The program provides two streams of funding support, including:

- Stream A: Funding to support feasibility studies of larger renewable energy projects (up to $250,000 funding for projects that result in greater than 4000 tonnes of GHG reductions over the projects' lifecycle).

- Stream B: Funding to support the design and construction of renewable energy projects integrated with new and existing community buildings (up to $100,000 per project).

The program is delivered centrally in the National Capital Region by staff in the Environment and Renewable Resources Directorate, within AANDC's Northern Affairs Organization. Public Servants review applications using eligibility criteria and then fund a third party technical review of eligible projects to determine potential GHG reductions. Following these assessments, a Project Review Committee comprised of representatives from Northern Affairs Organization, other departmental sectors, and external advisors consider all eligible projects and recommend the most appropriate projects for funding. The Director of the Climate Change Division then approves projects for completion, based on funding levels available.

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

At the departmental level, ecoENERGY is one of six sub-programsFootnote 2 under AANDC's broader Infrastructure and Capacity program area. These six sub-programs have a collective expected result that "First Nations communities have a base of infrastructure that protects the health and safety and enables engagement in the economy". The programs support the Land and Economy Strategic Outcome: "Full participation of First Nations, Métis, Non-Status Indians and Inuit individuals and communities in the economy".

The ecoENERGY program seeks to achieve the following results:

Immediate Outcomes:

- Aboriginal and northern communities have viable renewable energy projects that are under development (Stream A)

- Aboriginal and northern communities have energy projects integrated with new and existing community buildings (Stream B)

Intermediate Outcomes: - Reduced greenhouse gas emissions in Aboriginal and northern communities

Ultimate Outcome: - First Nations communities have a base of infrastructure that protects the health and safety and enables engagement in the economy

Strategic Outcome: - Full participation of First Nations, Métis, Non-Status Indians and Inuit individuals and communities in the economy.

This evaluation assessed the extent to which the ecoENERGY program is achieving these results.

1.2.3 Program Resources

Through the Aboriginal and Northern Community Action Program, AANDC provided $30 million over three years (2003-04 to 2005-06) to build the capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to undertake energy efficiency and renewable energy projects. In 2007, through Government of Canada's Clean Air Agenda, AANDC received $15 million over four years (2007-08 to 2010-11) to implement the ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Program. The program funded community energy planning, integration of small renewable technologies into community buildings and feasibility work for larger renewable energy projects.

The current ecoENERGY program was renewed in 2011, and received $20 million over five years (2011-12 to 2015-16). The program funds the integration of small renewable technologies into community buildings and feasibility work for larger renewable energy projects. As the ecoENERGY program has developed, it has increasingly focused on funding off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities.

From 2011 to 2014, the program spent an average of $850,000 per year on salaries and employee benefits, and $330,000 on operation and maintenance,Footnote 3 in order to distribute $2.8 million in grants and contributions to approved recipient communities.

As of April 1, 2014, program activities are supported by the Terms and Conditions of two Transfer Payment Program Authorities:

- Contribution for promoting the safe use, development, conservation and protection of the North's natural resources and promoting scientific development; and

- Contributions to support the construction and maintenance of community infrastructure.Footnote 4

Project funding is allocated to approved recipients using Contribution Agreements. Any ecoENERGY-funded project is included in existing agreements. Contribution Agreements are prepared by the program staff at Headquarters for any recipient community that does not already have one in place.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined ecoENERGY program activities undertaken from April 2011 to December 2014. The evaluation's Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in June 2014. Field work was conducted between July and December 2014.

In accordance with Treasury Board Secretariat requirements, the evaluation provides credible and neutral information on the relevance and performance of the ecoENERGY program. It also provides information to support future programming development, including possible alternatives, best practices and lessons learned. The evaluation builds upon the results of the 2010 Impact Evaluation and analyzes the results of actions taken to address the 2010 evaluation recommendations.

2.2 Evaluation Methodology

This evaluation focused on the following evaluation issues:

Program Relevance

Issue 1: Continued Need

Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Issue 3: Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Program Performance

Issue 4: Effectiveness

- Aboriginal and northern communities have viable renewable energy projects that are under development (Stream A);

- Aboriginal and northern communities have energy projects integrated with new and existing community buildings (Stream B);

- Reduced GHG emissions in Aboriginal and northern communities; and

- First Nations communities have a base of infrastructure that protects the health and safety and enables engagement in the economy.

Issue 5: Efficiency and Economy

The evaluation's findings and conclusions concerning the five core issues are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following lines of evidence.

Literature Review

A review of relevant and recent academic literature was completed by the external consulting firm, Kishk Anaquot Health Research. The purpose of the review was to define the term "renewable energy," highlight national and international policy drivers of renewable energy, outline Canadian federal roles and responsibilities, compare the need for renewable energy technologies in on-grid versus off-grid communities, compare the utility of funding various types of renewable energy technologies, highlight best practices for developing a successful policy and program from national and international examples, and provide direction for the evolution of AANDC's ecoENERGY program, based on an assessment of these findings.

Document and File Review

Program documentation and project files were reviewed, including core program design, delivery and financial authority documentation, meeting minutes, strategic planning documents, performance measurement documents and analysis, GHG reduction analyses, presentations to Parliament, and a sample of project proposals and final reports.

Database Analysis

An analysis of the program's project database was conducted. The database tracked the types of projects funded each year, the community location, whether the community was on or off-grid, project costs, estimated GHG reductions and the status of previously-funded stream A projects, such as feasibility studies.

Key Informant Interviews

A total of twenty-six interviews were conducted; eight with AANDC employees in the National Capital Region, eight with regional AANDC employees, and ten with external experts, including academics, consultants and other federal government departments.

Case Studies/Community Site Visits

Nine case studies were completed in British Columbia, Yukon and in Atlantic Canada, which included site visits to Kluane First Nation, Eel Ground First Nation, Abegweit First Nation, Penelakut First Nation, Taku River Tlingit First Nation, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and two other funding recipients where the ecoENERGY project was not successful. The case studies were chosen based on the following criteria:

- Examples of Stream A and Stream B completed projects;

- Regional spread;

- Regions with the highest number of funded projects;

- Where possible, focus on northern and off-grid communities to support the current evolution of the program;

- Recipients that were funded over multiple years;

- Highest ecoENERGY financial investments;

- Sample of communities funded under the previous program to demonstrate long-term impacts and lessons learned due to the fact that projects typically take at least five years to develop; and

- Sample of recipients where project was deemed a failure and/or money was returned.

The case studies included interviews with 25 project stakeholders, such as community members, external project contractors, engineers, project managers, plant operators, and Chief and council members. Key project documentation, including original proposals, project designs, status reports and final reports was also reviewed during these case studies.

2.2.1 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

The program tracked the necessary data to support its Performance Measurement Strategy. This allowed evaluators to assess the program's performance over the last three years. Recent evaluation work completed for AANDC's First Nation Infrastructure Fund, the Strategic Partnership Initiative, and Investments in Economic Development also allowed evaluators to utilize additional interview notes and case study notes where the ecoENERGY program was specifically mentioned to support this evaluation.

2.3 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of the AANDC Audit and Evaluation Sector managed and completed the evaluation according to EPMRB 's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process, which is aligned with the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation. External consulting firm, Kishk Anaquot Health Research completed a literature review to inform the evaluation. Quality control was also performed by the advisory role of the Evaluation Working Group consisting of ecoENERGY program managers, analysts, regional program stakeholders and representatives from AANDC's other infrastructure program, which was established to ensure the quality and relevance of the evaluation approach, research instruments and to review the draft deliverables. A quality review of the final evaluation report was also completed by AANDC's Strategic Research Branch.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

3.1 Program Need

Finding 1: There is a continued need for the Government of Canada to reduce GHG emissions.

The ecoENERGY for Aboriginal and Northern Communities program was developed to facilitate the integration of proven renewable energy technologies in Aboriginal and northern communities in order to reduce GHG emissions.

Renewable energy is secured from natural resources that are perpetually replenished: it is inexhaustible, sustainable energy that comes in many forms such as moving water (e.g., rivers and tides), wind, the earth and sunshine.Footnote 5 Some of the more recognizable forms of renewable energy include:

- Solar: solar photovoltaic, solar heating and concentrated solar power;

- Wind: on- and off-shore;

- Hydro: run-of-the-river and reservoir;

- Ocean/marine: including wave and tidal energyFootnote 6;

- Geothermal; and

- Bioenergy: includes biofuels and biomass that can be open-loop (i.e., generated from forests and wastes) or closed loop (i.e., generated from dedicated energy crops); biofuels and biomass are renewable resources only if the rate of their consumption does not exceed the rate of their regeneration.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

The ultimate objective of the ecoENERGY program is to harness the above mentioned renewable energy technologies in order to decrease GHG emissions. This objective is consistent with the internationally accepted conclusion that GHG emissions negatively impact global climates and therefore need to be reduced. According to the most recent Climate Change Performance Index (2014) published by GermanWatch and the Climate Action Network in Europe, no single country is on track to prevent dangerous climate change.Footnote 9 Despite significant investments in renewable energy, Canada, China and the United States rank poorly on the Index, with Canada faring the worst of western industrialized states.Footnote 10

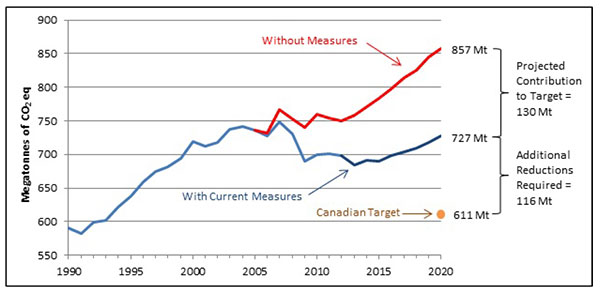

According to Canada's Emissions Trends 2014 report, Canada's emissions of CO2 have been steadily increasing since 1990 and, if no regulated action is taken, are expected to reach 727 megatonnes by 2020.Footnote 11 The remaining gap between the projection for 2020 and Canada's GHG emissions target under the 2009 Copenhagen Accord is estimated to be 116 Mt CO2 eq as demonstrated in the following historical graph.Footnote 12

Figure 1: Canada's historical greenhouse gas emissions and projections to 2020Footnote 13

Text alternative for Figure 1: Canada's historical greenhouse gas emissions and projections to 2020

The Y-axis of this line graph represents "Megatonnes of CO2eq". It begins at 550 instead of zero and increases by increments of 50 up to 900. The X-axis represents years, from 1990 to 2020. The Canadian target for greenhouse gas emissions is labelled as a point on the graph as 611Mt in the year 2020. The lines on the graph indicate that with current measures, Canada is projected to emit 727Mt of greenhouse gases by 2020, and without any measures, Canada is projected to hit 857Mt by 2020.

The following consequences are highlighted as potentially impacting Canadian communities if GHG emissions are not curtailed:Footnote 14

Environmental impacts

- Overall average annual temperatures are expected to increase.

- Global warming will decrease snow, sea ice and glacier coverage, resulting in rising sea levels and increased coastal flooding. Rising temperatures will also thaw permafrost in the Arctic.

- Storms and heat waves are likely to increase in frequency and severity.

- Many wild species will have difficulty adapting to a warmer climate and will likely experience greater stress from diseases and invasive species.

Human health impacts

- People living in Canada's northern communities, and vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly, are expected to be the most affected by the changes.

- Increased temperatures and more frequent and severe extreme weather events could lead to increased risks of death from dehydration and heat stroke, and injuries from intense local weather changes.

- There may be an increased risk of respiratory and cardiovascular problems and certain types of cancers, as temperatures rise and exacerbate air pollution.

- The risk of water-, food-, vector- and rodent-borne diseases may increase.

Economic impacts

- Agriculture, forestry, tourism and recreation could be affected by changing weather patterns.

- Human health impacts are expected to place additional economic stress on health and social support systems.

- Damage to infrastructure (e.g., roads and bridges) from extreme weather events is expected to increase.

As such, at a national level, there is a definite need for programs like ecoENERGY that contribute towards the reduction of GHG emissions in Canadian communities.

Finding 2: There is a continued need to fund renewable energy and energy efficient projects in Aboriginal and northern communities that: 1) replace diesel systems; 2) off-set high energy costs; and 3) support economic development.

Although the main objective of the ecoENERGY program has been to reduce GHG emissions, for communities that have submitted project proposals, the need for developing renewable energy technology is more personal. Communities are less concerned about an overall reduction of GHG emissions and instead are highlighting that there is a need for renewable energy solutions that reduce their dependence on diesel systems, that off-sets their high energy costs and that supports economic development.

1) Off-grid communities undertaking renewable energy projects to reduce their reliance on diesel generators

"Energy is obscenely expensive for off-grid communities." – Interviewee

As reported by the Department, there are 292 off-grid communities in Canada, and more than half (167) are Aboriginal or northern communities, with 77 off-grid communities and diesel dependent communitiesFootnote 15 above the 60th parallel and 90 off-grid communities south of the 60th parallel.Footnote 16 For these communities, renewable energy technology is being harnessed to reduce their dependence on diesel as the transportation, storage and consumption of diesel is expensive, poses risks for contamination, creates noise pollution and negatively impacts local air quality. The costs are well beyond what most Canadians pay for a kilowatt hour of electricity. Additionally, Aboriginal and northern off-grid communities are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Their incomes tend to rely on the land, water and other natural resources, and rising temperatures have increased the cost and difficulty of diesel generation for communities who use ice roads as the primary method of diesel transportation.Footnote 17 Footnote 18 Footnote 19 Footnote 20 Footnote 21 Footnote 22

AANDC funds the supply of diesel to off-grid reserves to support electricity and heat generation. Although the exact numbers could not be calculated due to financial coding restraints, these costs are estimated to be high due to the need for transporting fuel by air, sea and winter roads. For example, the Ontario regional office estimates that since 2005-06 the fuel freight differential, provided to communities to address fuel pressures related to remote electricity generation, totaled $46.8 million dispersed to 25 off-grid communities. Although the price of fuel has fluctuated over the years, AANDC has experienced a particularly large funding pressure from 2006 to 2009 when off-grid communities needed to request additional funds to support the rising cost of diesel fuel. These funding pressures may continue into the future as the cost of diesel in northern Ontario is projected to increase by 40 percent in the next 10 years.Footnote 23

In addition, provincial/territorial utilities also experience high costs to provide power to off-grid communities within their service area. These costs are particularly high in the North. According to the National Energy Board, "the North accounts for only about 0.3 percent of Canada's population and energy use," but "with a population of just over 100,000 dispersed over 3.5 million square kilometers, the costs and logistics of energy distribution is a major issue."Footnote 24 For example, Nunavut is completely dependent on imported diesel to support everyday living. The Nunavut power utility, Qulliq Energy Corporation, provides power to over 33,000 people in 25 communities, all of which are serviced by isolated diesel grids spread out across approximately two million square kilometers.Footnote 25 In 2009-10, in order to provide energy to its customers, Qulliq Energy Corporation utilized 45 million litres of diesel fuel at a cost of $39 million, or $1,181 per person.Footnote 26 The significant volume and cost of diesel fuel consumed in the generation of energy for Aboriginal and northern off-grid communities demonstrate a continued need to fund renewable energy projects that have the potential to dramatically reduce communities' use of diesel generators.

Diesel fuel is shipped to remote off-grid communities in the summer months and stored in tank farms for distribution and use throughout the year. The transportation and storage of diesel in communities also creates significant environmental issues as spills and leaks can cause contamination and impact local water sources and waterways.Footnote 27 Although the purchase and maintenance of fuel tanks are the responsibility of each community, when fuel tanks leak the contaminated site and potential environmental and health risks associated with the leak, it becomes the responsibility of AANDC. As a result of this risk, AANDC supports fuel tank upgrades and has provided an additional $80 million over the last five years to support the upgrade of older fuel tanks on-reserve and an additional $75 million will be allocated over the next four years.

Further compounding the energy issues facing off-grid communities is the growth in their electricity demand. Natural Resources Canada estimates that electricity demand in Canada's northern regions is growing at 1.5-2.0 percent per capita per year.Footnote 28 Increasing demand for electricity results in larger quantities of diesel being required by diesel-dependent communities in order to meet the needs of the community. Difficulties transporting diesel to remote diesel-dependent communities impact the ability of communities to meet increasing electricity demands and can result in power outages.Footnote 29 In many communities, the diesel-powered system cannot meet the demand placed on it, and fails, resulting in power outages. These power outages can last for a few hours or a few weeks and make the operation of community infrastructure such as schools, band offices and health centres very challenging.Footnote 30 Such power outages also restrict economic development in off-grid Aboriginal and northern communities as high energy costs and unreliable provision of power limits the effective operation of businesses and makes attracting investors particularly difficult.Footnote 31

2) On-grid communities undertaking renewable energy projects to reduce electricity costs

"It’s about bringing energy costs down." – Interviewee

Electricity prices for residential customers vary significantly across Canada. In regions such as Alberta, Saskatchewan and Atlantic Canada, residential electricity rates can be approximately double the cost charged in regions with significant hydro-electric resources, such as British Columbia, Manitoba and Quebec. For example, the average prices for residential customers for a monthly consumption of 1,000 kWh from 2010-2014 was 6.88⊄/kWh provided by Hydro Quebec, 7.47 ⊄/kWh provided by Manitoba Hydro and 8.57⊄/kWh provided by BC Hydro.Footnote 32 In contrast, the average price for residential customers over the same period and with the same usage was 13.32 ⊄/kWh provided by SaskPower, 14.60⊄/kWh provided by Nova Scotia Power and 15.06 ⊄/kWh provided by Maritime Electric in Prince Edward Island.Footnote 33 In addition, both SaskPower and Maritime Electric have higher service charges and/or energy charges for rural customers, making costs higher for rural customers, including many First Nations.Footnote 34

"…our remote communities are in the most trouble, they are also most aware of the true cost of energy. [This program] helps them learn more about the value of energy… that there are choices and costs and pros and cons and how important it is to choose wisely." – Interviewee

These higher costs are consistent with information provided by case study interviewees, particularly those from Atlantic Canada who were able to significantly reduce their energy bills by utilizing solar panel technology. Interviewees identified that a key reason for communities to participate in the ecoENERGY program was to use renewable energy systems to reduce their electricity and heating costs. It became evident to evaluators that even on-grid Aboriginal and northern communities struggle with significant electricity and heating costs for band-owned and operated buildings. Many of these buildings are used extensively by community members and therefore draw electricity and heat for a substantial number of hours annually. For some communities, the high electricity costs in certain regions have severely impacted the community's operating budget limiting their ability to address other community priorities. Therefore, for some on-grid communities in regions with higher energy costs, there is a need for renewable energy systems to help off-set energy costs.

3) On-grid communities who are undertaking renewable energy projects as an economic development opportunity

"On the economic development side, energy as a whole in the region is a huge topic for First Nations." – Interviewee

The ecoENERGY program also provided a valuable opportunity for Aboriginal and northern communities who possess territory, or have access to crown land, that has the natural features necessary for larger renewable energy projects. For example, several large renewable energy projects, such as micro-hydro facilities and solar/wind farms, have been developed by communities with funding from ecoENERGY. These projects often provide on-grid communities with an opportunity to develop power purchase agreements with provincial/territorial utilities to sell the power they produce to the grid. These projects can provide significant income for communities that can be reinvested into other economic development opportunities or used to address other community needs. According to a Lumos Energy report completed for AANDC in 2012, "Large hydro also represents one of the most substantive types of economic development opportunity for First Nation, Métis and Inuit communities, during construction and in operation. Such developments tend to kick-start a range of spinoff economic activities, often in more remote and rural regions of the country. For [these reasons] it is timely and important for AANDC to study large hydro developments across Canada."Footnote 35

However, these projects require significant funding to complete. The early stages of developing large renewable energy projects are particularly challenging as a large number of studies are required to establish the viability of the project. Communities often struggle to find funding sources for the exploratory phase, which is integral, as it produces the results that are used to attract additional funding partners.

Overall, the evaluation has found that there is a continued need for ecoENERGY funding for renewable energy projects to support the provision of energy and heat to reduce GHG emissions as well as to reduce diesel consumption and associated risks, to reduce costs and as an opportunity for economic development.

Finding 3: International examples demonstrate that there is a continued need for an ecoENERGY program that focuses on off-grid and northern communities.

Interviews with program management made it clear that the ecoENERGY program needs to shift its focus from funding a wide variety of projects across Canada to instead targeting communities with the greatest need for renewable energy solutions. As such, the program has been moving toward prioritizing project proposals received from remote, off-grid, diesel-dependent communities, which are located both in the northern portions of provinces and north of the 60th parallel. In order to identify whether this program evolution meets a need that the program should continue to address, evaluators relied on the literature review to provide best practices and lessons learned from the international arena.

The literature review found that since 2008, the United States government has made it a priority to develop a substantial renewable energy environment in the northern state of Alaska. It has infused significant financial and human resources, including $202.5 million for 227 projects since 2008 into the Alaskan state to advance renewable energy technology.Footnote 36 The Government completed a full assessment of each community, with a high-level snapshot of the least-cost options for electricity, space heating, and transportation for each community.Footnote 37 Additionally, in June 2008, a Diesel Efficiency Workgroup was formed to focus on reducing diesel fuel consumption in rural communities through generation and distribution efficiency measures.Footnote 38 A third-party evaluation of Alaska's Renewable Energy Fund in 2012 estimated that the first 62 projects funded will ultimately provide a net present value benefit of more than $1 billion over their lifetime. These projects cost $508 million.Footnote 39

The key area to note from Alaska's experience is that the coordination of research and projects was completed on-location, by Alaska Energy Authority personnel. This was done to develop the capacity and accountability of the staff on-site, and to ensure that "Alaskans have access to energy information and a single location they can work with to resolve their energy challenges and opportunities." The intent of the Alaskan State government is to use the information collected by Alaska Energy Authority staff to inform future decision making. By encouraging the development of on-site staff, the Alaska Energy Authority "…concentrate[d] expertise in the governing bodies to allow years of well-informed policy and programming development."Footnote 40 A major partner in this work was the United States Office of Indian Energy, which focuses exclusively on the advancement of energy security in Indigenous American communities. The partnership of these stakeholders at the community-level allowed tribal governments to improve energy efficiency and facilitated their transition to renewable energy systems.Footnote 41

The Alaskan government also forged strong partnerships with academic institutions and research centers, such as the Alaska Building Science Network,Footnote 42 to advance its renewable energy agenda. Footnote 43 The Alaska Center for Energy and Power at the University of Alaska in particular developed a comparative database that identifies technologies options and limitations for each identified resource. Going forward, AANDC may be able to develop a similar database to identify appropriate technology options for Canada's northern communities in order to provide recommendations to communities seeking support.

Parallel to the Alaska experience, AANDC's remote and northern communities have had many high-quality energy plans developed over the years, but few have come to fruition. For Alaska, the answer was to "engage Alaskans in the solution and invite their active participation in the selection and ownership of their alternative energy sources."Footnote 44 Although AANDC has a significantly smaller budget than Alaska ($20 million over five years for all of Canada compared to $50 million per year for the state of Alaska alone), Canada could use the lessons learned from Alaska's experience, and better engage local stakeholders in the research and investments in targeted northern communities.

The literature review also confirmed that a focus on off-grid or rural communities for renewable energy system development is an international best practice, which has been followed by Australia, China, and Germany. In Australia, renewable energy programmingFootnote 45 is predominately focused on off-grid communities that include indigenous communities.Footnote 46 Footnote 47 Footnote 48

Historically China has preferred grid extensions, but has more recently focused on stand-alone (i.e. not grid-connected) systems that have gained favour as their reliability and affordability have improved. A particular focus has been on targeting remote and poverty-stricken minority settlements with a combination of hydro, solar, wind, geothermal, biomass and other technologies. China's reported key to success (99 percent of rural residents with electricity) is the Government's commitment to community-based planning and long-term funding.Footnote 49 Footnote 50

In 2010, Germany developed the Renewable Energy Sources Act that provided for a full suite of incentives and subsidies supporting the deployment of renewable energy; this made Germany a leader in the transition to renewable energy. Although none of Germany's communities are "remote", the country's reported key to successful policy implementation was a focus on community ownership through cooperative initiatives.Footnote 51 Profits from community-owned renewable energy systems were directed into kindergartens, sport facilities, and gathering places.Footnote 52 Germany's experience affirms the utility for AANDC to continue to invest in supporting the development of renewable energy systems in community buildings as cost savings from public expenditures can be leveraged to provide additional community programs and services.

Further, the International Energy Agency highlighted that a successful renewable energy strategy must include a stable and enabling policy framework that allows for community engagement and ownership, favourable markets, including providing subsidies to encourage use, building community capacity and facilitating understanding and awareness of renewable energy.

3.2 Alignment with Roles and Responsibilities

Finding 4: The ecoENERGY program is aligned with roles and responsibilities of the federal government, and specifically, the mandate of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

This evaluation found that the roles and responsibilities of the federal government and AANDC are complex and interconnected with provincial and territorial responsibilities. Numerous federal, provincial and territorial funding programs have existed and continue to evolve to facilitate the development of technologies, adapt technologies to northern conditions, increase capacity related to renewable energy generation in communities, and to implement renewable energy projects.

Provinces and territories have the predominant role and responsibility to provide energy to communities while the federal government supports the integration of the renewable energy sector nationally.

"Diesel energy is preferred in the North, because it is consistent. This is the concern: Consistency. Spending money on feasibility studies is what helps move the mindset and give confidence in pursuing renewable energy technology. People are afraid to take the risk to switch from diesel to a less confident source. There needs to be a gradual switching over of technologies. It’s going to take a lot of time to get out of diesel completely… that’s why [the government] needs to demonstrate results." – Interviewee

To date, the provinces and territories have been the primary promoters of energy conservation, while the federal government has tended to provide support to the provinces and territories in identifying and then promoting proven renewable energy technologies through a consistent national approach. The role of the federal government in supporting provincial and territorial governments in developing renewable energy powers is supported in the literature. Specifically, according to the International Energy Agency, a national renewable energy policy thrives when there is a government framework to facilitate industry-led research and development, until the renewable energy sector expands to become predictable, nimble, and credible. Efforts must also include actions to reduce economic barriers to facilitate the implementation of renewable energy technology. Once renewable energy policies are developed, and renewable technology is both publically accepted and highly integrated into the existing infrastructure, the federal government may phase out its targeted government support.Footnote 53 At this stage, AANDC's role is therefore to facilitate the visibility and viability of renewable energy technologies in on-reserve and northern communities until the time comes when these technologies are easily accessible and accepted as mainstream public investments as well as when provincial and territorial policy frameworks can ensure the sustainability of such systems.

Having a federal program that is aimed at promoting the adoption of renewable energy technologies to reduce GHG emissions is also aligned with international trends. The percentage of countries in every income bracket with national renewable energy policies has steadily increased over the past decade. The United Nations General Assembly declared the upcoming decade (i.e., 2014-2024) as the "Decade of Sustainable Energy for All,"Footnote 54 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that an immediate transition to cleaner energy is imperative to mitigating catastrophic consequences;Footnote 55 and the world's largest economies and most intensive GHG emitters (accounting for more than a third of all global GHG emissions), China and the United States have announced plans to dramatically reduce carbon emissions. The United States has pledged to cut GHG emissions to 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, while China targets to peak CO2 emissions around 2030 or earlier by increasing non-fossil fuel emitting energy production to 20 percent of total production by 2030. These commitments are recognized as foundational to more rigorous efforts world-wide. More formalized commitments are expected to be negotiated in advance of the 2015 United Nation's Climate Change Conference (COP 21) in Paris, France.Footnote 56

Provincial and territorial governments have jurisdiction and regulation over electrical production, transmission and distribution. Each province and territory also has a Public Utilities Act establishing a board or council to provide decisions and recommendations with respect to the operation of public or private utilities that are responsible for power generation and distribution. This evaluation found that each province and territory has been implementing a spectrum of energy efficiency/conservation investments as well as providing incentives for encouraging the introduction of renewable energy systems. The following graph identifies the total number of incentives, initiatives or programs (not the total investment) in each province and territory.

Figure 2: Energy Incentives in Canadian Provinces and TerritoriesFootnote 57

Text alternative for Figure 2 Energy Incentives in Canadian Provinces and Territories

This bar graph portrays the energy incentives in Canadian provinces and territories. The Y-axis states all of the provinces and territories. In order from top to bottom, they are: PEI, NFLD, NS, NB, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, BC, NWT, Yukon, and Nunavut. The X-axis represents the number of incentives, initiatives, or programs (IIP) in each province, marked from 0 to 60, in increments of 20. A colour-based legend states four various stages of, and approaches to, energy use: Efficiency/conservation; oil; gas; and potential for renewable.

Only four provinces have more than 20 incentives, initiatives, or programs (IIP) in place. They are Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and BC. Of those four, Ontario and BC have over 40 IIPs in place. These four provinces all deal with the same three issues: efficiency/conservation, gas, and potential for renewable energy.

Nunavut is the only province or territory that has no IIPs at all.

PEI and NFLD only have IIPs focused on the issue of efficiency/conservation. NS, NB, Saskatchewan, and Yukon have IIPs that deal with two issues: efficiency/conservation and the potential for renewable energy.

Alberta’s IIPs deal almost equally with three issues: efficiency/conservations, oil, and gas. Northwest Territories deals with three issues: efficiency/conservation, oil, and potential for renewable energy.

Alberta and NB target efficiency/conservation least often. Quebec and NWT spend about half of their IIPs on efficiency/conservation. Every other province uses the majority of their IIPs to target efficiency/conservation.

As demonstrated in the above graph, the main focus for provincial and territorial governments has been to support energy conservation and improve efficiency of existing energy technology. Beyond programs and incentives, provincial and territorial governments across Canada also have a variety of regulatory instruments to promote the use of renewable energy systems, including:

- offset programs where a premium rate can be paid on your utility bill to create new renewable energy systems that would replace or ';off set' your home or building consumption with renewable sources;

- procurement through requests for proposals or actually seeking to amplify the amount of renewable energy by requesting bids from renewable energy suppliers;

- standard offering, feed in tariff and subsidy programs that offer a premium rate for renewable energy;

- legislated renewable portfolio standards or an obligation for utilities to produce a set amount of renewable energy;

- net billing that allows producers of renewable energy to sell their excess energy to the utility grid; and

- net metering that provides consumers who are also generating renewable energy the option to connect to the utility grid to offset their consumption, stay connected to the utility and meet their energy needs with their own systems if the utility is unable to provide.

Alberta has an off-set program and all other provinces have requests for proposals. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island have legislated renewable portfolio standards. Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and British Columbia have standard offer and subsidy programs. The following table highlights the suite of renewable energy policies by province and territory.

| Province | Renewable Energy target |

Off Set | Procurement of Renewable Energy |

Standard offer and Feed in Tariff |

Renewable Portfolio Standards |

Net bill | Net meter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Alberta | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Saskatchewan | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Manitoba | Yes | ||||||

| Ontario | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Québec | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| New Brunswick | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Nova Scotia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Prince Edward Island | Yes | Yes | Yes (Wind only) |

Yes | Yes | ||

| Yukon | Energy Strategy, a commitment to increase the supply and use of renewable energy 20% by 2020 | ||||||

| Northwest Territories | Renewable Energy Fund to subsidize renewable energy generation: Hydro, biomass and solar energy strategies | ||||||

| Nunavut | Ikummatiit, a territorial energy strategy that focuses on alternative energy sources and efficient use of energy was planned but never implemented | ||||||

As many as one hundred Canadian municipalities also have GHG emission reduction plans.Footnote 61 Footnote 62

Although these provincial and territorial programs are often made available to on-reserve communities, they are primarily implemented in off-reserve communities. AANDC provides similar programming to on-reserve communities.

It is evident from these examples that there is a clear role for the federal government to advance the adoption of renewable energy technologies while provincial and territorial governments focus on increasing the efficiencies of existing energy infrastructure and developing a supportive investment environment. However, it is also evident that the roles and responsibilities of various federal departments can overlap, especially in the North where AANDC is less bound by its Indian Act commitments and where other federal departments provide significant support.

Although, as shown above, AANDC does not have a direct mandate to invest in supporting renewable energy technologies, the Department has made the policy decision to invest in renewable energy technologies in Aboriginal and northern communities across Canada in order to further its social and economic mandate. The Literature Review confirmed that there are social, political and economic reasons to advance the use of renewable energy technology beyond reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Renewable energy technology can have far-reaching impacts on community health, education, and the environment. It can also provide improved energy access and security, assist with poverty reduction, tackle gender equality, and provide job creation and rural economic development.Footnote 63,Footnote 64,Footnote 65 The Aboriginal and northern communities that fall under AANDC's mandate, require sustainable and reliable energy to enable them to participate fully in Canada's political, social and economic development. By focusing on integrating renewable energy technologies into off-grid communities, AANDC can reduce diesel operating costs, prolong the life of existing energy production assets, support community growth, and build sustainable communities.Footnote 66

In addition, there are economic, social, and environmental programming areas that fall under AANDC's mandate that are impacted by energy challenges. Challenges from underperforming energy infrastructure and disruptions in energy supply limit the impacts of AANDC's economic development programming. The fluctuating costs of fuel, the increasing cost of transporting fuel and increasing demand from a rapidly increasing population are putting pressure on AANDC's budget while also increasing air pollutants from the burning of diesel. Environmental challenges also include fuel spills associated with transportation, local storage and fuel transfers resulting in environmental damage to sensitive habitats where clean-up responsibilities falls under AANDC's mandate. By resolving these energy challenges through sustainable energy solutions, AANDC programming areas can flourish. Thus, AANDC's role in the support for renewable energy technology projects is multi-dimensional.

By choosing to invest in renewable energy technologies, AANDC is contributing to greater energy security and sustainability for Aboriginal and northern communities in Canada.Footnote 67 Once established and operational, locally-managed energy systems will promote local economic development opportunities, facilitate private sector partnerships, increase employment and skills development, and meet the demands of growing populations. Increasing renewable energy supply will reduce air pollutants and reduce fuel spills and contamination, thus improving human health and preserving the local environment. A reduced reliance on imported fossil fuels coupled with improved energy efficiency reduces energy costs. In general, improved energy infrastructure will result in more sustainable and secure energy sources, diversified economic opportunities and stronger, more self-sufficient communities, fulfilling AANDC's mandate.

Overlapping roles and responsibilities exist north of the 60th parallel between AANDC and Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency with respect to the development of renewable energy projects

South of the 60th parallel, AANDC has a clear role in providing support to on-reserve communities for renewable energy projects, in line with Canadian and international commitments to reduce GHG emissions. In the North, AANDC's specific roles and responsibilities associated with energy generation, storage and distribution are complex as energy regimes differ in each of the three territories.Footnote 68 Energy regimes vary according to: the level of devolution of responsibilities from federal to territorial governments; Aboriginal rights negotiated through treaties, land claims and self-government agreements; and territorial authority over licensing and permitting requirements on energy service providers. The territories' legislated roles, mandates, and their proximity to northern citizens, call for territorial governments to play the most direct role of any jurisdiction in ensuring the availability of the local energy supply as part of the overall social and economic well-being of their regions. Each of the territorial governments has established public utilities that are charged with developing energy supplies for their territory, and investing in generation, transmission, and distribution of energy when private corporations will not. Yukon and the Northwest Territories also have privately-owned utilities.Footnote 69

"In the North, the needs are basic: jobs, cost savings, energy security." – Interviewee

In the North where there are few reserve communities, AANDC has a less structured role in enabling the development and implementation of infrastructure, including energy projects. AANDC's mandate is in fact to support Northerners in their efforts to improve social well-being and economic prosperity, develop healthier and more self-sufficient communities and participate more fully in Canada's political, social and economic development to the benefit of all Canadians – which could arguably include supporting renewable energy projects. In Nunavut specifically where work is still being conducted to complete a final devolution agreement and where a Nunavut Energy Strategy has not yet been implemented, AANDC has a clear role to support the development and implementation of energy projects. However, in the devolved territories of the Yukon and Northwest Territories, the territorial governments, like provincial governments, have a clear role in providing energy services. AANDC's role is further complicated by other departments and agencies that also share in responsibilities related to energy generation in the North. The Energy Sector of Natural Resources Canada is the lead on energy policy, clean energy research and technology development; and Natural Resources Canada is also the knowledge centre for scientific expertise on clean energy technologies for the Government for Canada.Footnote 70 The National Energy Board has a goal to promote safety and security, environmental protection and efficient energy infrastructure and markets in the Canadian public interest within the mandate set by Parliament in the regulation of pipelines, energy development and trade. The newly established Canadian High Arctic Research Station will focus on introducing renewable energy systems to Canada's North, which includes not only north of the 60th parallel, but the northern portions of territories as well.Footnote 71 Finally, the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency has responsibilities for improving the economic base of the North (north of the 60th parallel), which can include harnessing renewable energy technologies.Footnote 72

Although many federal partners are involved in the research, development and implementation of renewable energy technologies, Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency's mandate directly overlaps with AANDC's north of the 60th parallel. Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, once a component of AANDC, is now a regional development agency that works with partners and stakeholders to advance sustainable economic diversification in Canada's three territories by funding programs and by undertaking policy development and research. Although Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency does not support renewable energy specifically, it can and has funded renewable energy projects, which often fit within the terms and conditions of Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency's Strategic Investments in Northern Economic Development program.Footnote 73,Footnote 74 Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency has funded several large, renewable energy programs in the Northwest Territories and in the Yukon.Footnote 75

Overlapping roles and responsibilities exists between multiple sectors within AANDC who provide funding for the development of renewable energy projects