Evaluation of Engagement and Policy Development

Final Report

Date: April 2014

Project Number: 1570-7/12038

PDF Version (337 Kb, 44 Pages)

Table of contents

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Abroginal Affairs and Northern Development |

|---|---|

| C & PD |

Consultation and Policy Development |

| EPMRB |

Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch |

| ETC |

Education and Training Commission |

| FSIN | Federation of Saskatchewan Indians |

Executive Summary

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook an evaluation of Engagement and Policy DevelopmentFootnote 1 at AANDC as per its approved five-year Evaluation and Performance Measurement Plan. The purpose of the evaluation was to obtain evidence-based information on the relevance, performance and efficiency and economy of the AANDC spending authority: Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development (C & PD authority). The evaluation includes data and information from the fiscal period of 2008-2009 through 2012-2013.

The purpose of the C & PD authority is to provide support to Indians, Inuit and Innu so that AANDC may obtain their input on policy and program developments. The authority enables the provision of funding on a proposal/project basis to stakeholders to engage with the Department in areas across a range of policies and programming. Over the longer term, this should result in better informed policy, improved relations, and support for AANDC's policies. Spending through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period from 2008-2009 through 2012-2013 totaled $128.7 million.

The C & PD authority supports engagements not otherwise covered by a specific program authority. In addition, consultations triggered by the Crown's legal duty to consult are not part of the C & PD authority. Only those engagements supported by the C & PD authority were considered in this evaluation while those supported under program authorities and the legal duty to consult were excluded.

Key Findings: Relevance

The evaluation found that there is a need for meaningful engagement between AANDC and Aboriginal people and organizations as engagements can enhance the understanding of key issues, improve relationships, and in turn, the design and delivery of policies and programs. Consultation and engagement is especially important at AANDC where it plays an important role in the Department's day-to-day activities and is an essential element in the fulfilment of its vision for Aboriginal people and communities. Through consultation and engagement activities, AANDC gains a greater understanding of the perspectives of a wide range of Aboriginal stakeholders and experts. This understanding helps the Department to develop better, more informed and more effective policies and programs for Aboriginal peoplesFootnote 2.

In addition, engagement is also a key step to strengthening the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the government of Canada and contributes to the ongoing process of reconciliation, which is a key priority for Aboriginal peoples and the federal government. As the C & PD authority facilitates dialogue between the Department and its stakeholders, it supports the fulfillment of this objective.

Key Findings: Performance

The C & PD authority is intended to be a vehicle for a wide range of engagements between AANDC and Aboriginal people for the development and implementation of departmental policy and programming. The specific types of eligible activities are workshops, studies, meetings, and policy development, all for subject matter related to AANDC policy and programming. The evaluation found that such flexibility is desirable given that C & PD funding is used across the range of AANDC activities and Aboriginal peoples in Canada. However, the flexibility of the C & PD authority, combined with its decentralized management structure, enables funding for initiatives or ongoing support that might fit better under an existing or amended/consolidated program authority. Overall, the C & PD authority generally focuses more on supporting the basic existence of recipient organizations, rather than on engagement activities that are designed and implemented according to the principles of well run stakeholder consultations. In addition, there is minimal advice and guidance available for AANDC personnel involved in engagements that are not related to the legal duty to consult.

The design and delivery of C & PD as well as its performance reporting did not support a thorough assessment of the achievement of expected outcomes for the C & PD authority. However, where the evaluation was able to determine that the funding was used to conduct typical engagement activities related to policy and program development, the evaluation was able to conclude that these engagements have generally:

- Contributed to enhanced awareness among AANDC personnel of the positions of Aboriginal peoples with respect to AANDC policy and program agendas;

- Contributed to enhanced awareness among Aboriginal peoples with respect to AANDC policy and program agendas; and

- In some cases, C & PD contributed to enhancing Aboriginal influence on departmental programs and policy.

The level and extent of Aboriginal involvement is impacted by consultation fatigue, which occurs when Aboriginal groups do not have the capacity to adequately participate in the consultation activities. The evaluation found that appropriate coordination and consistency, particularly a set of overarching principals to help guide engagement processes and set realistic goals, would help to reduce the likelihood of consultation fatigue as well as to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of engagement activities.

Recommendations

- Review and revise as appropriate the Basic Organizational Capacity and Consultation and Policy Development authorities' expected results in order to provide greater clarity and distinction between the two.

- Provide advice, guidance, and tools to AANDC personnel involved in engagements not triggered by the legal duty to consult and continue to support the flexibility and broad application of the Consultation and Policy Development Authority.

- Clarify recipient reporting requirements associated with funding through the Consultation and Policy Development authority. As part of this work, andin keeping with AANDC's Performance Measurement Strategy Action Plan, the expected results for the Consultation and PolicyDevelopment authority should be included in the Performance Measurement Strategy for the Consultation and Accommodation Sub-Program.

- Track the engagements supported by the Consultation and Policy Development authority. The tracking tool should include the type of activity, the purpose, the location, and participants involved in the engagement activity.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of Engagement and Policy Development

Project Number: 1570-7/12038

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Review and revise as appropriate the Basic Organizational Capacity and Consultation and Policy Development authorities’ expected results in order to provide greater clarity and distinction between the two. | The two authorities are under different parts of the Program Alignment Architecture. This is a challenge that can be addressed in cooperation with the Integrated Planning team in the Policy and Strategic Direction and the Audit and Evaluation Branch. The Policy on funding to Aboriginal Representative Organizations - principally Basic Organizational Capacity - will be updated over the 2014 year as a result of decisions taken in the approach to funding for Aboriginal Representative Organizations. Considerations for changes to the authorities will include expanding the list of eligible recipients to include Métis and non-status Indian organizations/people. |

Director General, Policy and Strategic Direction | December 2015 |

| 2) Provide advice, guidance, and tools to AANDC personnel involved in engagements not triggered by the legal duty to consult and continue to support the flexibility and broad application of the Consultation and Policy Development Authority. | Agree. The Manager of the FAME team in the Aboriginal and External Relations Branch is the departmental steward for C & PD. Planning in terms of communications and effective implementation of the Consultation and Policy Development authority will be required, including a review of the workload and performance objectives of the FAME team. | Director General, Aboriginal and External Relations Branch | December 2015 |

| 3) Clarify recipient reporting requirements associated with funding through the Consultation and Policy Development authority. As part of this work, and in keeping with AANDC's Performance Measurement Strategy Action Plan, the expected results for the Consultation and Policy Development authority should be included in the Performance Measurement Strategy for the Consultation and Accommodation Sub-Program. | The reporting requirements were required to align to the General Project Report Data Collection Instrument, which replaced the C & PD reporting form as of April 1, 2014, as per direction from Chief Financial Officer, Policy and Strategic Direction and Audit and Evaluation Sector. Work on the Annual Report will be supported by Policy and Strategic Direction, including this element. In consultation with Integrated Reporting branch regarding the new Program Alignment Architecture for 2015-16, it was confirmed that the authority is no longer considered a program in the Program Alignment Architecture as of April 1, 2015, and will be part of a consolidated Performance Measurement Strategy for the Consultation and Accommodation Sub-Program. |

Director General, Aboriginal and External Relations Branch Director General, Planning, Research and Statistics Branch | December 2015 |

| 4) Track the engagements supported by the Consultation and Policy Development authority. The tracking tool should include the type of activity, the purpose, the location, and participants involved in the engagement activity. | Agree. This will involve the FAME group doing the tracking further to examining various options on how best to track within current resource allocations. This will provide better tracking of results/performance of this authority vis à vis engagement activities. | Director General, Aboriginal and External Relations Branch | September 30, 2014 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on April 11, 2014, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed on April 14, 2014, by:

Josée Touchette

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Policy and Strategic Direction

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) undertook an evaluation of Engagement and Policy DevelopmentFootnote 3 at AANDC as per its approved five-year Evaluation and Performance Measurement Plan. The evaluation was conducted in order to inform policy and expenditure management decisions as well as program improvements and public reporting. The evaluation follows the guidelines set by Treasury Board's Evaluation Policy (2009) and examines the relevance of the AANDC Contributions for the Purpose of Consultation and Policy Development (C & PD) authority, its performance in meeting intended objectives and its efficiency and economy.

The evaluation includes program data and information from the fiscal period of 2008-2009 through 2012-2013. Spending through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period totaled $128.7 million, with approximately 43.4 million (34 percent) attributable to Headquarters and approximately 83.1 million (66 percent) attributable to regions. At Headquarters, the Policy and Strategic Direction Sector was the largest user (24.7 million - 61.3 percent of Headquarters spending) and among regions, Ontario region was the biggest user (26.6 million - 32 percent of regional spending).

As the C & PD authority exists to support engagements not otherwise covered by a specific program authority; it is not specific to any single issue or program and it may be used by any program/region in the Department. In addition, consultations triggered by the Crown's legal duty to consult are not part of the C & PD authority. Only those engagements supported by the C & PD authority were considered in this evaluation while those supported under program authorities and the legal duty to consult were excluded. By limiting the evaluation scope in this way, AANDC engagements can be seen as an activity with intended outcomes that are not program-specific and can be applied across the Department.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Effective engagement, as part of the collaborative process promoted by AANDC, is an important part of good governance, sound policy development, decision making and good relationships. In 1976, Cabinet approved an approach, as a matter of policy, to consult with Indians, Inuit and Innu on the development of programs and services affecting their quality of life. Through funding under the C & PD authority, Aboriginal peoplesFootnote 4 are consulted on key program and policy developments. The input obtained is to be used to shape policy and programs, resulting in better, more effective policies and programs that are easier to implement and respond to community needs and structures.

Some examples of high-profile collaborative efforts between AANDC and Aboriginal people and organizations during the evaluation period include:

- The Statement of Apology delivered in June 2008, further confirmed the federal government's desire to work closely with Aboriginal people by speaking to "a new beginning and an opportunity to move forward together in partnership".

- In June 2009, the federal government introduced the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development. This new Framework adopts a modern and comprehensive approach to Aboriginal economic development that puts an emphasis on building strategic partnerships.

- The Crown-First Nations Gathering, held in January 2012, built on the Canada-First Nations Joint Action Plan, agreed to by the Government of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations in June 2011. Both parties committed to advancing a constructive relationship based on the core principles of mutual understanding, respect, ensuring mutually acceptable outcomes and accountability.

Engagement with recipients is a department-wide activity conducted by many AANDC program areas and encompasses a wide and extensive variety of subjects and players. Some program authorities include provisions to provide funding for consultative work as a matter of program operations. However, sometimes the content or topic of a proposed engagement does not align with any existing program authority. For example, the extensive engagements required for developing legislation for Matrimonial Real Property were supported through C & PD because the topic was not covered under any existing AANDC program authority. Similarly, initiatives or ideas originating with First Nations/Aboriginal peoples may be aligned with AANDC priorities and require engagements but sometimes do not "fit" an existing authority. Where this lack of fit exists, there may be no program authority for supporting Aboriginal involvement/engagement. The C & PD authority is designed to fill such gaps as it allows the Department to support Aboriginal people and organizations to participate in engagements while maintaining flexibility on the topics, priorities and initiatives to be considered and making collaborative involvement between AANDC and Aboriginal peoples possible.

1.2.2 Activities, Objectives and Expected Outcomes

According to program documentation, the key activities performed by departmental officers under the C & PD authority are: identifying key stakeholders; receiving and assessing funding proposals; developing and managing contribution agreements; supporting engagement sessions; and seeking advice and input from stakeholders on policy and program development.

The purpose of monies flowed through the C & PD authority is to provide support to Indians, Inuit and Innu so that AANDC may obtain their input on policy and program developments. The authority enables the provision of funding on a proposal/project basis to stakeholders to engage with the Department in areas across a range of policies and programming. Over the longer term, this should result in better informed policy, improved relations, and support for AANDC's policies.

The following expected outcomes for the C & PD authority appear in the 2010 Performance Measurement StrategyFootnote 5.

Immediate

- Departmental staff is aware of the position of stakeholders with respect to a policy or program agenda.

- Status Indian, Inuit and Innu organizations, their supporting members and elected officials are made aware of the Department's objectives with respect to a policy or program agenda.

Intermediate

- Engagement with stakeholders influences the development of policies and programs.

Ultimate

- Policies and programs achieve effective outcomes.

1.2.3 Program Activity Architecture and Performance Measurement Framework Alignment

C & PD is part of the Cooperative Relationships program activity in the AANDC Program Alignment Architecture. As such, C & PD supports the AANDC Government Strategic Outcome - "Good governance and co-operative relationships for First Nations, Inuit and Northerners". It is notable, however, that the expected results of the C & PD authority, as seen in program documentation, can be understood in terms of the whole range of AANDC programming. Although engagement between AANDC and Aboriginal peoples supports the Cooperative Relationships Strategic Outcome, consultations and engagements are relevant for the whole department. Accordingly, the C & PD authority is not specific to any single issue or program and it may be used by any program/region in the Department.

The following output-level objectives were identified for C & PD in the 2011-12 Departmental Performance Measurement Framework: Policy, technical, process and financial support provided to internal and external stakeholders in relation […] to research, policy and program development.

These program outputs complement the outcomes from the Performance Measurement Strategy and will be used in this evaluation.

1.2.4 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

Under the authority's Terms and Conditions, the authority to approve, sign and amend agreements along with approving payments is delegated to program directors and regional directors. This delegation of authority sets up a decentralized management structure to fit with the horizontal and broad nature of this authority.

The Intergovernmental and International Relations Directorate, within the Policy and Strategic Direction Sector, performs an overall co-ordination role within the decentralized management structure of the authority. According to program documentation, its co-ordination responsibilities include:

- the renewal of the authority, as required;

- the development of reviews and evaluations, as required; and

- the development and implementation of performance measurement along with its supporting tools and reports.

Responsibilities for AANDC program directors and regional directors managing activities under the authority include:

- Negotiating, reviewing and approving work plans and project deliverables;

- Reviewing and assessing applications for funding;

- Managing contribution agreements for results;

- Receiving and reviewing recipient reports;

- Participating in the collection and analysis of data to be used in evaluating performance indicators;

- Participating, as required, in authority renewal and evaluation processes; and

- Carrying out recipient audits, as warranted.

1.2.5 Stakeholders

The stakeholders for C & PD include:

- Indian, Inuit and Innu individuals, on or off reserve;

- Indian Bands / Inuit Settlements;

- District Councils / Chiefs Councils;

- Indian and Inuit Associations / Organizations;

- Tribal Councils;

- Other Indian/Inuit Communities;

- Indian and Inuit Economic Institutions / Organizations / Corporations;

- Partnerships (or Groups) of Indians / Inuit;

- Beneficiaries of comprehensive land claims and/or self-government agreements with any group of Indians, Inuit and Innu;

- Indian Education Authorities;

- Indian Child Welfare Agencies;

- Cultural Education Centres;

- Indian and Inuit Co-operatives; and

- Boards and Commissions.

1.2.6 Program Resources*

C & PD funding is provided on a project basis linked to a proposal or application. Program directors and regional directors have delegated authorities to receive applications for funding and approve them in accordance with the Terms and Conditions. These directors are accountable for negotiating agreements, defining deliverables, and establishing project reporting requirements as well as for ongoing monitoring of agreements and identifying and resolving any potential issues that may arise. Recipients are accountable to AANDC for carrying out the agreed activities, reporting, maintaining appropriate financial systems and administrative records, and cooperating in evaluation or audit activities.

Spending through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period totaled $128.7 million, with approximately 43.4 million (34 percent) attributable to Headquarters and approximately 83.1 million (66 percent) attributable to regions. At Headquarters, the Policy and Strategic Direction Sector was the largest user (24.7 million - 61.3 percent of Headquarters spending) and among regions, the Ontario region was the biggest user (26.6 million - 32 percent of regional spending).

| 08-09 | 09-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | 12-13 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vote 10 - Grants and Contributions | $22.9M | $25.4M | $24.4M | $27.2M | $28.8M | 128.7M |

| *Financial data extracted from the AANDC OASIS Financial System. Note: There is no Vote 1 monies (i.e., Operations and Maintenance) associated with the C & PD authority. |

||||||

| 08-09 | 09-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | 12-13 | Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEADQUARTERS | ||||||

| Policy and Strategic Direction | 5,313 | 4,967 | 3,209 | 4,288 | 6,893 | 24,671 |

| Executive Direction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 376 | 376 |

| Regional Operations | 604 | 512 | 2,741 | 2,008 | 2,623 | 8,487 |

| Resolution and Indian Affairs | 0 | 20 | 100 | 3,884 | 0 | 4,004 |

| Northern Affairs | 251 | 395 | 663 | 0 | 0 | 1,309 |

| Office of the Federal Interlocutor | 145 | 605 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 910 |

| Educational and Social Development Programs and Partnerships | 0 | 200 | 150 | 0 | 50 | 400 |

| Lands and Economic Development | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treaties and Aboriginal Government | 20 | 171 | 0 | 0 | 3,039 | 3,230 |

| Headquarters Sub-totals | 6,333 | 6,870 | 6,863 | 10,180 | 13,141 | 43,387 |

| REGIONS | Totals | |||||

| Ontario | 4,590 | 5,697 | 5,493 | 5,493 | 5,289 | 26,562 |

| Saskatchewan | 2,654 | 3,741 | 3,374 | 3,354 | 3,012 | 16,134 |

| British Columbia | 3,024 | 2,552 | 2,863 | 2,771 | 1,539 | 12,749 |

| Manitoba | 2,864 | 2,378 | 2,009 | 198 | 2,006 | 9,456 |

| Alberta | 1,926 | 1,897 | 1,849 | 1,977 | 1,846 | 9,494 |

| Atlantic | 384 | 759 | 1,175 | 856 | 1,313 | 4,487 |

| Quebec | 720 | 885 | 620 | 477 | 365 | 3,066 |

| Northwest Territories | 112 | 200 | 87 | 66 | 66 | 532 |

| Yukon | 131 | 102 | 4 | 91 | 50 | 377 |

| Nunavut | 0 | 67 | 96 | 0 | 138 | 301 |

| Regional sub-total | 16,405 | 18,277 | 17,570 | 15,283 | 15,642 | 83,177 |

| AANDC grand totals | 22,738 | 25,146 | 24,433 | 25,463 | 28,783 | 126,563 |

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation of the C & PD authority examined activities funded over the period 2008-2009 through 2012-2013.

Since most AANDC program authorities include provisions for the conduct of engagement with Aboriginal organizations/peoples that are affected by the Department's policies and programs, some engagements happen without the use of the C & PD authority. Only those engagements supported by the C & PD authority were considered in this evaluation while those supported under program authorities were excluded. The evaluation assessed the C & PD authority and its use in terms of relevance, design and delivery, and performance (i.e., the results achieved in relation to the intended objectives for projects funded under the C & PD authority).

The Terms of Reference for this evaluation were approved by the AANDC Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in November 2012. The evaluation is designed to examine only engagement activities related to AANDC policy and/or programming; consultations triggered by the Crown's legal duty to consult were not includedFootnote 7.

Reviews of literature and documentation began in late 2012, while interviews, surveys and case studies were conducted from February 2013 through July 2013. The evaluation took into account a number of variables such as: regions where the project took place and the size of consultation projects/activities (e.g., materiality).

Karen Ginsberg Management Consulting, Inc, was contracted to undertake the case studies (see Section 2.3).

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference and Treasury Board requirements for evaluations, the evaluation focused on the following evaluation issues:

Relevance

- Continued Need

- Is there an ongoing need for the authority?

- Alignment with Government Priorities

- Is the authority consistent with government priorities and AANDC strategic objectives?

- Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- Is there a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government in engagements?

Performance

- Effectiveness (i.e. Success)

- To what extent have intended outcomes been achieved as a result of the authority?

- What are the factors (both internal and external) that have facilitated and hindered the achievement of outcomes (e.g. human resources, policy, governance)?

- Have there been unintended (positive or negative) outcomes? Were actions taken as a result of these?

- To what extent has the design and delivery facilitated the achievement of outcomes and its overall effectiveness?

- Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

- Is the most economical and efficient means of achieving the intended objectives employed?

- How could the authority be improved?

In addition to these evaluation issues, best practices, lessons learned and alternatives were also explored. The evaluation also explored AANDC's policies on gender analysis and sustainable development as they relate to engagements between AANDC and its clients.

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The evaluation findings and conclusions are based on the analysis of information collected using a range of techniques. These techniques as well as the major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report are described in this section.

2.3.1 Data and Information Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following lines of evidence:

- Literature Review and Media Scan:

The literature review and media scan examined the broader trends, issues, challenges and best practices related to consultation generally and, particularly, between governments and their associated Aboriginal peoples. - Document and File Review:

A document and file review was conducted to investigate questions of program relevance, achievement of outcomes, design and delivery, and efficiency/economy. The evaluation team identified activities funded through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period by looking at "Budget Allocation/Expenditure Status Reports" as housed in the Grants and Contributions Information Management SystemFootnote 8. Although these particular reports are not designed to provide (comprehensive) information about the impacts of engagement projects or reflect alignment with the C & PD Terms and Conditions, they provided the names of projects, the responsibility centre managers, the recipients and the dollar amounts associated with all C & PD spending over the evaluation period. These reports formed the foundation from which recipient reporting samples and case study topics were drawn.

The following documents were reviewed:- Program Documentation;

- Treasury Board submissions;

- Previous audits, evaluations, management responses and action plans and follow-ups;

- Reports from recipients;

- External communications and reports (e.g., proposals and workplans);

- Departmental databases (i.e., Grants and Contributions Information Management System);

- Documents related to the management of the C & PD authority (e.g., Performance Measurement Strategy, Management Control Framework).

- Public communications (e.g., the AANDC website).

- Key Informant Interviews:

A total of 31 interviewees provided in-depth information, including facts, insights and opinions that provide input on a range of evaluation issues. Interviews were conducted with AANDC officials from both Headquarters (14) and regions (10), and with representatives from recipient organizations (seven) that received funding through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period.

To identify potential interviewees, the evaluation team ran reports in the AANDC First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment system to determine which responsibility centre managersFootnote 9 flowed money through the C & PD authority and which recipients received C & PD funding over the evaluation period. Then, the Government Electronic Directory Service was used to link the responsibility centre managers with current AANDC personnel (where possible). To identify projects with relatively large and small materiality, a shortlist was generated by identifying the largest spending amounts and those around $100,000Footnote 10. Then, the evaluation team contacted the responsibility centre managers associated with these projects to invite them to take part in an interview for the evaluation. This "cold call" method was employed because of the decentralised management structure of the authority. That is, as there was no primary or central entity to supply a list of potential interviewees, it was necessary for the evaluation team to identify them through other means, in this instance using First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment.

Recipient interviewees were identified in a similar manner. The evaluation team identified the recipient organizations that received C & PD funding over the evaluation period and then contacted them, inviting their representatives for an interview. - Case Studies

Five case studies on AANDC engagement activities were conducted. These case studies, which included reviews of literature and documentation as well as interviews (18 in total), provided a sample of cases in which the C & PD authority was used to support recipients' participation in engagement activities. The case studies shed light on the variety of ways in which the C & PD authority is used. The case studies were identified based on the advice of AANDC personnel involved in engagements and by using Grants and Contributions Information Management System to identify engagement activities funded through the C & PD authority over the evaluation period. The following five case studies were conducted on engagements related to following: 1) the Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada; 2) Matrimonial Real Property; 3) Measuring Active Measures; 4) the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nation's (FSIN) Education Commission; and 5) the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Treaty Relations Coordinator.

2.3.2 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

The C & PD Authority Supports Engagement Activities Across the Department

The authority is not program-specific. That is, the authority is not "owned" by any specific program entity and contributes to multiple AANDC Strategic Outcomes. Rather, it is a vehicle to facilitate the development and implementation of departmental policies and programs by ensuring that AANDC obtains the input of Aboriginal people and organizations on all policy and program developments. This evaluation is focused on a practice that is important for the Department and for Aboriginal people alike; it is not an evaluation of a single program entity.

It is important to note that the authority is just one vehicle for the conduct of engagements between AANDC and its recipients. Ordinary program authorities may include provisions for the conduct of engagement with Aboriginal organizations/peoples that are affected by the Department's policies and programs. The C & PD authority is designed for supporting Aboriginal participation in engagements while not limiting them to certain topics or approaches. The engagements covered by this evaluation are to be seen as examples that were, for a variety of reasons, funded through the C & PD authority rather than program authorities.

Decentralised Management Structure Contributed to Challenges in Collecting Information

The evaluation was conducted in the absence of any one AANDC entity that supports, or is accountable for, the conduct of engagements across the Department. Although the management is decentralised, the Aboriginal and External Relations Branch performs an overall co-ordinating role, with responsibilities such as renewal of the authority as required, contributions to evaluations, and the development and implementation of tools and reports for performance measurement. However, the Aboriginal and External Relations Branch is not involved in planning, conducting or monitoring any of the engagements. As a result of this decentralized management structure, the evaluation was conducted with limited guidance or input.

The decentralised nature of the authority contributed to a shortage of information concerning the organizations involved, the purpose of the activities, and the outputs and outcomes associated with C & PD funding over the evaluation period. To overcome this challenge, the evaluation team constructed a picture of what activities had been funded by sampling information contained in Grants and Contributions Information Management System and by conducting interviews. However, the reporting information drawn from Grants and Contributions Information Management System was not sufficient for a full understanding of the results of engagement activities because it tended to focus on activities related to process, such as the number of meetings held, leaving the achievement of results to be assumed or inferred.

2.3 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The EPMRB of the AANDC Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority for the evaluation and managed according to EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process, which is aligned with Treasury Board policy on Evaluation.Footnote 11 The methodology and final reports were peer-reviewed by EPMRB personnel for quality assurance.

A Working Group was established to provide advice and guidance on key elements of the evaluation. The Working Group included program representatives, stakeholders and partners as necessary.

The work for this evaluation was completed by EPMRB staff (the C & PD evaluation team). The case studies were completed by a consultant, K Ginsberg under the oversight C & PD evaluation team, headed by the Evaluation Manager.

3. Relevance

Findings

3.1 Continued Need

3.1.1 There is a need for meaningful engagement between AANDC and its recipients as it enhances relationships and, in turn, the design and delivery of policies and programs.

3.1.2 The flexibility and broad applicability of the C & PD authority allows AANDC to support Aboriginal groups in engagements that are not program-specific (e.g., support for Aboriginal participation in the Crown-First Nations Gathering).

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

3.2.1 Engagements conducted by the C & PD authority support: federal goals for enhancing its relationship with Aboriginal people and organizations; and, each of the Department's Strategic Outcomes, particularly that of Cooperative Relationships.

3.2.2 Flexibility in the topics and approaches for consultations affords recognition and integration of Aboriginal priorities when they are aligned with departmental policy and program development.

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

3.3.1 The C & PD authority is consistent with the AANDC mandate to support Aboriginal people in their efforts to participate more fully in Canada's political, social and economic development - to the benefit of all Canadians.

3.1 Continued Need

3.1.1 There is a need for meaningful engagement between AANDC and its recipients as engagements can enhance the understanding of key issues, improve relationships, and in turn, the design and delivery of policies and programs.

Over time, consulting Canadians on issues that affect their lives has gradually become a fundamental principle of parliamentary democracy in Canada and part of the culture of the federal public service. Today, there is a greater emphasis on consultation and engagement than ever before and this corresponds to growing expectations from all Canadians for more accessible, responsive and accountable governance. Canadians generally want to be consulted by their government to discuss the values that underlie program and policy options and the trade-offs and choices facing decision makers. Consultation and engagement processes that involve deliberation, reflection and learning to achieve common ground can help to address the expectations of all Canadians, including Aboriginal peoples.

Consultation is a process for sharing information, getting public input, analysing the input and using it to inform policy and program development, and to develop effective solutions. The process helps to identify the range of affected parties; minimize the risk of unexpected consequences; and to discover better implementation methods. Involving interested parties in policy and program development is also effective in increasing trust and engagement by promoting transparency and accountability, and improving awareness and understanding of the area under concern. Consultation is also a tool to encourage public ownership of policies and programs, thereby increasing public commitment.

Consultation and engagement is especially important at AANDC where it plays an important role in the Department's day-to-day activities and is an essential element in the fulfilment of its vision for Aboriginal people and communities. Through consultation and engagement activities, AANDC gains a greater understanding of the perspectives of a wide range of Aboriginal stakeholders and experts. This understanding helps the Department to develop better, more informed and more effective policies and programs for Aboriginal peoples.

In addition, consultation is also a key step to strengthening the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Government of Canada and contributes to the ongoing process of reconciliation. Designing and implementing good policy and programming can depend on obtaining the input and support of all involved, which in turn, can depend on good relationships.

Strengthening relations is a key part of the C & PD authority. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, "Strengthening relations with citizens is a sound investment in better policy-making and a core element of good governance. It allows government to tap new sources of policy-relevant ideas, information and resources when making decisions. Equally important, it contributes to building public trust in government, raising the quality of democracy and strengthening civic capacity. Such efforts help strengthen representative democracy, in which parliaments play a central role."Footnote 12

The importance of involving Aboriginal people in the programs, policies and services affecting them is reflected in a variety of public statements and documents, including, among others, the June 3, 2011, Speech from the Throne and AANDC Reports on Plans and Priorities. Moreover, the AANDC website contains numerous references to the engagement imperative.

AANDC interviewees were unanimous in agreeing that engagements between the Department and Aboriginal people and organizations are crucial for making their respective positions known and understood to one another. Specifically, they stated that it is incumbent upon the Department to engage with Aboriginal peoples, on its policies, programs and legislation. As a result of effective engagement, Aboriginal stakeholders will have greater influence in the policies and programming that affect them, resulting in "… better, more effective, policies and programs that are easier to implement and respond to community needs and structures." Furthermore, program documentation states that it is designed to support Aboriginal capacity for such participation in all policy and program development.

As AANDC works in partnership with its stakeholders and clients, relationships are an important part of the Department's ongoing work and initiatives. AANDC communications and public reporting reflect the importance of these partnerships and the good relationships they support.Footnote 13Footnote 14

The idea that meaningful engagement between AANDC and Aboriginal peoples contributes to good relationships was a recurring theme with interviewees. Moreover, the Department has acknowledged in its Corporate Risk Profile that the failure to build and sustain strong, productive and respectful relationships with Aboriginal peoples is among its most significant risks and could threaten the delivery of its mandate.Footnote 15 The potential consequences of such failure include, among others, failure to improve conditions in vulnerable communities, lost opportunities for Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal youth, increased costs to Canada and public protests. Aboriginal political movements and happenings (Idle No More, for example) demonstrate the frustration felt by many Aboriginal groups that perceive there to be insufficient engagement by government on matters affecting them. In this regard, mechanisms that facilitate effective engagements are crucial. Without these mechanisms, the C & PD authority being one example, the feeling that engagements with Aboriginal people and organizations are insufficient could be even stronger and relationships weakened accordingly. The C & PD authority is designed to support effective engagement and, in turn, to help mitigate risks that could affect the relationship between AANDC and Aboriginal people and organizations.

3.1.2 The flexibility and broad applicability of the C & PD authority allows AANDC to support Aboriginal groups in engagements that are not program-specific (e.g., support for Aboriginal participation in the Crown-First Nations Gathering)

The C & PD authority is not program-specific so it can be used to support engagements on a variety of departmental and Aboriginal initiatives, helping AANDC officials across the Department to be responsive to the needs of Aboriginal stakeholders and to address priorities. Moreover, the authority's flexibility makes it possible for the Department to solicit Aboriginal perspectives on topics that do not fit under a program-specific authority. For example, AANDC conducted national engagements with organizations such as the Assembly of First Nations and Native Women's Association of Canada to obtain their input on the development of legislation for Matrimonial Real Property on reserveFootnote 16 and its implementation. Without the flexibility of the C & PD authority, it would have been difficult or impossible for the Department to fund the participation of organizations such as these. As a consequence, their perspectives and concerns would not have directly informed the legislation and its implementation.

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities and AANDC Strategic Outcomes

3.2.1 Engagements conducted by the C & PD authority support the federal goal of enhancing its relationship with Aboriginal peoples as well as each of the Department's Strategic Outcomes, particularly that of Cooperative Relationships.

As noted in speeches from the Throne,Footnote 17 federal budgetsFootnote 18 and through public communicationsFootnote 19, the Government of Canada endorses a partnership approach. This partnership approach is particularly important in matters of interest to Aboriginal people and organizations because of the unique relationship between the Crown and Aboriginal people in Canada.Footnote 20

The importance of actively engaging stakeholders is a common theme in the Department's planning and reportingFootnote 21 as well as its public communications. The AANDC website has a section dedicated to Consultation and Engagement, which states:

"AANDC is a Department that at its fundamental core, works in continuous partnership with several stakeholders and primarily with First Nation, Inuit, Métis and Northerners groups to support sound policy development and decision making. AANDC seeks input from individuals, associations, organizations and other levels of government to help shape its policies, programs and legislative initiatives." Footnote 22

The C & PD authority furthers the departmental objective to improve the quality of life and foster self-reliance for First Nations, Inuit and Northerners by supporting Indians, Inuit and Innu to consult their communities and be in a position to provide input to the Department on its policy and programming initiatives. Thus, the authority supports the Departmental Strategic Outcome of "The Government" as its use by AANDC officials supports the Cooperative Relationships Program Activity, which has an Expected Result that "Relationships between parties will be based on trust, respect, understanding, shared responsibilities, accountability, rights and dialogue."Footnote 23 As the C & PD authority facilitates dialogue between the Department and its stakeholders, it supports the fulfillment of this objective.

The C & PD authority clearly supports the Cooperative Relationships Program Activity while simultaneously supporting multiple AANDC Strategic Outcomes and program objectives: program activities across the Department are entitled to use it to support engagement. Positioning C & PD in one place on the AANDC Program Alignment Architecture tends to characterize it as a traditional program when it is better understood as an overall approach to undertaking the Department's work and promoting good relationships with Aboriginal people and organizations, regardless of the program or policy topic at hand. In this sense, the C & PD authority supports the Department generally as opposed to supporting primarily one programming area and, as such, exists more as an internal service than a program activity.

3.2.2 Flexibility in the topics and approaches for engagements affords recognition and integration of Aboriginal priorities when they are aligned with departmental policy and program development.

According to program documentation, case studies, and key informant interviews, the C & PD authority functions to support a partnership approach to the development and implementation of AANDC programming and policy. However, the majority of interviewees stated that it is aligned with the priorities of Aboriginal people and organizations only to the extent that they are shared with those of the Department and the federal government. This means that emerging priorities might not be fully considered if they do not align with government priorities.

However, when considering Aboriginal priorities, it is important to note that in a democracy such as Canada's, elected representatives have the central role in bringing their constituents' perspectives to bear on matters of policy, legislation and expenditure. It is the responsibility of elected ministers to bring forward policies, programs and legislation that take into account all Canadians' views. Therefore, policy and program development activities related to Aboriginal people and organizations must also consider this broader perspective. Deputy ministers' policy advice must be mindful of the Minister's collective responsibility and ensure that advice is drawn from an appreciation of the government-wide agenda and the impacts of a particular initiative. In doing so, other departments often need to be consulted so that the views of the Prime Minister and other ministers are taken into account. The support and collaboration of other ministers may also be necessary for the success of a policy proposal, and the need to coordinate the responsibilities of several ministers in order to move initiatives forward is now the rule rather than the exception. Deputy ministers are expected to ensure that their departments perform these tasks and ensure attentiveness to the priorities of all Canadians from a "whole of government" perspective. Overall, as one small part of the policy-making process, the C & PD authority can help AANDC facilitate the consideration of Aboriginal priorities within this "whole of government' perspective by enhancing the awareness and understanding of departmental staff and Aboriginal people concerning a policy or program agenda.

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

3.3.1 The C & PD authority is consistent with the AANDC mandate to support Aboriginal people in their efforts to participate more fully in Canada's political, social and economic development to the benefit of all Canadians

The federal government's emphasis on partnerships together with its unique relationship with Aboriginal peoples Footnote 24 means that AANDC, the federal department with the most direct and extensive relationship with Aboriginal people and organizations, must ensure that Aboriginal peoples have opportunities to be involved as partners in the development of the policies and programming that affect them.

The emphasis on partnerships and relationships is commonly reflected in AANDC communications. For example, the Minister's Message in the 2011-12 Report on Plans and Priorities states that:

"The Government of Canada is committed to working with partners to set realistic goals that will help to improve the quality of life for residents of First Nations, Métis, Inuit and Northern Communities. By developing strong partnerships at all levels […] we can ensure that voices are heard and there is opportunity to participate in decision making."Footnote 25

In the 2012-13 Report on Plans and Priorities, the Minister references the importance of relationships:

"As stated at the historic Crown-First Nations Gathering held earlier this year, the Government of Canada is committed to strengthening the relationship with First Nations and to increase collaboration to develop the elements upon which our renewed relationship will be based."Footnote 26

The AANDC C & PD authority supports the Department's commitment to collaboration as well as the Department's mandated support for Aboriginals peoples in their efforts to improve their socio-economic status, health, sustainability, and participation in Canada's political, social and economic development.Footnote 27 In line with the C & PD authority's purpose of supporting Indians, Inuit and Innu to provide input to the Department, interviewees pointed out that AANDC has an important role to play in enabling Aboriginal involvement in decision making around the Department's policy and programming that affects them.

4. Design and Delivery

Findings

4.1 The flexibility of the C & PD authority combined with its decentralised management structure enables funding of core and core-like activities rather than engagement activities related to policy and program development and implementation.

4.2 There is minimal advice and guidance available for AANDC personnel involved in engagement that is not related to the legal duty to consult.

Types of Government ConsultationsFootnote 28

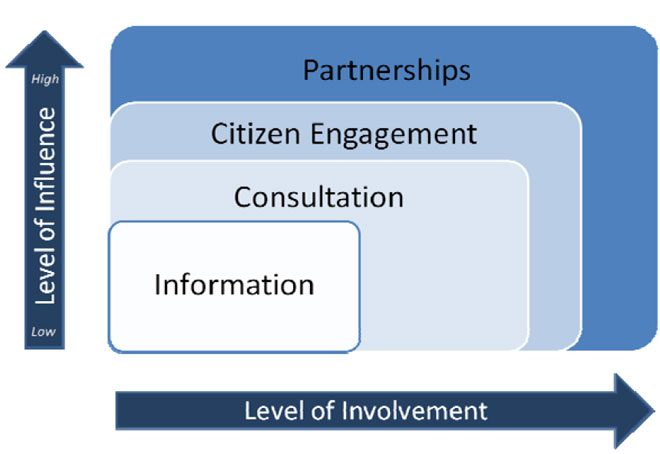

There is a range of approaches by which government institutions provide opportunities for Canadians to become involved in policy-making and the development of programs, services and initiatives. As illustrated in the figure below, these approaches form a continuum from the lowest degree of interaction to the highest. As the degree of interaction increases, the degree of influence grows, along with the amount of time and resources required.

Figure 1

Text alternative for Figure 1

Figure 1 depicts four types of government consultations along a continuum of involvement and influence from the lowest degree of involvement and influence to the highest. The four types of consultations are: information; consultation; citizen engagement; and, partnerships. The level of involvement is depicted by an arrow along the x axis and the level of influence is represented by an arrow along the y axis. Each of the four types of consultations is presented along the two axes in order of their level of involvement and influence. Information type consultations have the lowest level of involvement and influence followed by, consultation, citizenship engagement and partnerships.

At one end of the spectrum, the Government distributes or makes accessible information on policies, decisions, services, and legislation. This promotes transparency and accountability and better enables citizens to participate in the public policy process.

Further along the continuum, consultation and engagement processes invite greater citizen involvement in the development of policies, programs, services and initiatives. At the farthest end of the spectrum, shared decision making through partnerships provides the greatest degree of involvement. These approaches to public involvement often overlap, and each is employed according to the issue and context.

In the context of Aboriginal peoples, formal engagements that meet the Government's legal duty to consult are the highest level of consultations the Government engages in. These are high level, multifaceted talks that are a two way exchange of information. Furthermore, specific members of the Aboriginal community should be involved, the consultations usually follow a pre-determined and mutually accepted agenda.

Whether the process is called a consultation, an engagement, or a partnership, these processes often involve a two-way exchange of information that includes listening to others' ideas, seeking suggestions to solve problems, and outlining proposals while ensuring there are opportunities for change. It is important to take a broad view of the different forms of engagement. As per the C & PD outcomes, the aim should be that engagement with stakeholders influences the development of policies and program.

Consultation processes seek information, input and feedback from stakeholders on policies, programs, services or initiatives that affect them directly or in which they have an interest. Such consultations can range in intensity from sending letters or documents to seeking feedback from targeted participants through a series of national workshops and public meetings. They can also be organized as either ad hoc or ongoing processes.

As the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development notes, feedback is especially important part of the process. "Poorly designed and inadequate measures for information, consultation and active participation in policy-making can undermine government-citizen relations. Governments may seek to inform, consult and engage citizens in order to enhance the quality, credibility and legitimacy of their policy decisions...only to produce the opposite effect if citizens discover that their efforts to stay informed, provide feedback and actively participate are ignored, have no impact at all on decisions reached or remain unaccounted for."Footnote 29

Several federal departments and agencies have consultation policies, guidelines and tools in place to help ensure their engagements with stakeholders are conducted in an effective and meaningful way. No matter the objectives of the consultations and the stakeholders involved, the various policies and guidelines reflect common practices that are applicable to all consultations. According to the various guidelines, a well-run stakeholder consultation process is comprised of the following five key stages: 1) preparation; 2) design; 3) implementation; 4) feedback and follow-up; and 5) final evaluation and integration. These stages are implemented based on nine principles that form the foundation of each consultation process by creating the conditions necessary for a successful consultation. The principles are: commitment, evaluation, timing, inclusiveness, accessibility, clarity, accountability, transparency, and coordination.

Types of activities funded by C & PD

The C & PD authority is intended to be a vehicle for a wide range of engagements between AANDC and Aboriginal peoples for the development and implementation of departmental policy and programming. According to the C & PD Terms and Conditions, eligible activities are "those that investigate, develop, propose, review inform or consult on policy matters within the mandate of DIAND".Footnote 30 The specific types of eligible activities are workshops, studies, meetings, and policy development, all for subject matter related to AANDC policy and programming. Through the interview process and reviews of literature and documentation, the evaluation found that such flexibility is desirable given that C & PD funding is used across the range of AANDC activities and Aboriginal people and organizations peoples in Canada. If engagement processes and objectives are to reflect collaboration and partnership, then the Department should be positioned to respond to emerging issues and priorities that impact its mandate.

This flexibility, an obvious strength of the C & PD authority, can also be seen as a weakness. As noted in program documentation, the authority to approve, sign and amend agreements along with approving payments is delegated to program directors and regional directors. This decentralised management structure is aligned with the broad, flexible and horizontal nature of the C & PD authority. While it is clear that flexibility is required, the C & PD authority can be interpreted very loosely because of a lack of clarity around what can be funded or, perhaps more importantly, what cannot be funded. Such loose interpretations coupled with the decentralised management structure means that the C & PD authority can be used for initiatives or ongoing support that might fit better under an existing or amended/consolidated program authority. The authority often gets used to flow monies that may be justified, but fit better under another program authority because the funded activities are not always directly related to engagement initiatives. When monies are allocated in this way, the expected results that derive from consultations and the associated reporting will not occur.

The C & PD authority has been used to fund recipients to take part in engagements that were clearly eligible for funding, such as the Exploratory Process and First Nations Election Reform. Another example of proper use of C & PD funding was for the engagement process required in the development of the Matrimonial Real Property legislation. The impetus for this legislation was new in the sense that it fit under an existing AANDC program and, therefore, no existing authority could be used to flow money to fund engagements. The Matrimonial Real Property legislation is an example where C & PD funding was necessary to ensure that engagement and collaboration occurred in order to develop the legislation.

The spending associated with each of the case studies in this evaluation was justifiable in terms of AANDC's mandate. However, some of the case studies, as well as the sample of projects, demonstrate that the C & PD authority was used for initiatives that were not aligned well with its intended purpose and would have been better supported by some other sources. For example, the case study on support to the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs to Liaise with the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba found that the salary for an ongoing liaison position is supported by money flowed through the C & PD authority. Similarly, a second example of a lack of clarity in the use of the C & PD authority was revealed by the case study on the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians - Education and Training Commission (FSIN-ETC), which showed that C & PD funding is associated with work that, while related to engagement, is ongoing without specific objectives. While the necessity of the funding for the liaison positions at Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba and the FSIN-ETC is not considered here, it should be noted that C & PD funding is intended to support specific engagement initiatives linked with defined deliverables and outcomes that are related to policy and program development and implementation. Supporting an ongoing function using the C & PD authority suggests a mismatch and that the C & PD funding is sometimes used as "top-up" money to complement existing resources. Such cases could indicate issues around the level and use of funding as well as a lack of clarity concerning which authority should be used. The cases where the use of the C & PD authority to provide support may not be appropriate could be attributable, at least in part, to apparent confusion and overlap in the use of core and project funding. The intended purpose of the C & PD authority can be understood in the context of these two important types of funding provided to AANDC recipients. Core funding is designed to support the basic existence of a recipient organization and includes categories such as staff salaries and costs for basic maintenance and utilities. Project funding extends beyond these categories to include specific initiatives that, conceptually, have beginnings and ends. Projects (i.e., engagement activities) may be multi-year but they are not ongoing because they have a foreseeable end with clearly defined expected results. It is apparent in program documentation, including the Management Control Framework that the intent of the C & PD is for clearly defined engagement initiatives. However, as seen through the case studies, the sample C & PD funded activities, and interviews, currently C & PD focuses more on capacity building, and less on conducting engagements as per its intended results. In addition, initiatives without specific results and timelines received C & PD funding to support ongoing salaries, travel expenses and committee work.

The confusion between core funding and project funding to conduct consultations can be seen in the idea of "core-like" activities. Core-like activities are those that do not seem to fit neatly under either the core or project categories: they usually seem closely related to the raison d'être of the organization yet extend beyond basics such as buildings, utilities and salaries.

A comparison of the AANDC Basic Organizational Capacity authority and the C & PD authority reveals a potential source of confusion. The Basic Organizational Capacity authority, according to its title and in the opinion of interviewees, is intended to be for core operations, while the C & PD authority is to be dedicated to project funding for consultations on policy and program development and implementation. However, as noted in this evaluation, there appears to be confusion over their appropriate use for either core operations or funding for specific initiatives.

Overlap between the Basic Organizational Capacity and C & PD authorities is a central cause of confusion. Table 3 shows a comparison in the expected results of the Basic Organizational Capacity and C & PD authorities. Although it is the Basic Organizational Capacity expected results that tend to overlap with those of C & PD, evidence suggests that the erroneous use of the C & PD authority is attributable, at least in part, to the overlap and lack of clarity between them.

Table 3: Expected Results of the Basic Organizational Capacity and Consultation and Policy Development Authorities

| Contributions to support the basic organizational capacity of representative Aboriginal organizations (Basic Organizational Capacity) | Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development |

|---|---|

| Core organizational capacity to make Aboriginal organizations capable of contributing and participating in government policy and program development. | Active engagement of Status Indians, Innu and Inuit, their bands, communities and organizations in the development of the Government's legislative and policy agendas for Aboriginal peoples. |

| Better informed representative Aboriginal organizations, their members, and elected officials. | Better informed Aboriginal organizations, their supporting members, elected officials, as their input to departmental staff. |

| Identification and agreement among members on priorities for action and approaches to issues. | Increased understanding by all stakeholders of the issues. |

| Input to legislation, policies and programs so that they are more reflective of Aboriginal perspectives. | Broader understanding of the Government's intentions towards Aboriginal peoples. |

| Increase members' understanding, acceptance and support for the Government's Aboriginal policies. | Increased support and acceptance of government legislation and policy based on the input received from the Aboriginal community and their organizations. |

| Improvements in the relations between Aboriginal peoples and the federal government. | Improvement in the relations between status Indians, Inuit and Innu and the federal government. |

Unlike the last evaluation of the Basic Organizational Capacity and C & PD authorities,Footnote 31 which recommended that they be combined because of their apparent similarity, this evaluation recommends that their differences should be clarified. Making a sharper distinction between them should guard against core-like activities being funded by C & PD funding, and as a result, ensure that funding is allocated for engagement activities to inform policy and program development.

Recommendation #1

It is recommended that AANDC:

- Reviews and revises as appropriate the Basic Organizational Capacity and Consultation and Policy Development authorities' expected results in order to provide greater clarity and distinction between the two.

Support for AANDC Staff in Conducting Engagements

As noted in the section on Types of Government Consultations, well run stakeholder consultations must be thoroughly planned with clear objectives. However, AANDC does not have a framework to guide departmental engagements when they are not triggered by the legal duty to consult. Although a policy or programming initiative may require consultation for the sake of good governance, good relations, and policy and program development, AANDC managers receive little guidance if the legal duty is not triggered.Footnote 32,Footnote 33 AANDC does not have a designated entity or system to provide guidance and support to departmental managers so they can be better prepared to take a flexible approach to engagement while operating according to consistent principles.

Most interviewees supported the idea of a consistent approach to engagements between AANDC and Aboriginal people and organizations. They stated that a set of guiding principles, not a set definition or strict protocol, and a support system for personnel involved in engagements would promote consistency, more support from communities, better relationships and better results. This idea also emerged among the Aboriginal representatives interviewed for this evaluation as they maintained that the flexibility, although desirable, has contributed to inconsistencies in AANDC's approach to engagements.

Federal departments and agencies are free to set up guidelines/support systems to ensure their engagements with stakeholders are conducted in an effective and meaningful way. For example, Natural Resources Canada has a guide for its officials to conduct consultations with Aboriginal stakeholdersFootnote 34 and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans makes guidance on consultations available to its officials.Footnote 35 These guidelines include the practices and principles outlined above and are applicable to all consultations, including those conducted by AANDC officials. For example, the concepts of timeliness and clarity are particularly relevant for engagements that are intended to support policy and program development. When engagements begin at the earliest opportunity and continue as appropriate in a timely fashion, participants will have a reasonable amount of time to prepare and provide their input. Clarity around the process and expected outcomes of engagements is also a critical factor in that participants (i.e., the Aboriginal group(s) to be involved) need to know what their contributions should be and, importantly, how those contributions will be reflected in policy or programming. Following principles such as these will contribute positively to meaningful engagement between AANDC officials and Aboriginal peoples.

The expectations of parties involved in engagements are also of key importance. Expectations are largely based on effective communications and setting out clear objectives. There is a wide spectrum of possible objectives for engagements, and it is important for officials to ensure that they are properly articulated and communicated. For example, the main objective of an engagement might be sharing information about a decision already made or an initiative that is already complete. In such a case, officials should ensure that the stakeholders involved know that they will not be able to influence the decision - that the engagement is for information sharing only. At the opposite end of the spectrum, an engagement could involve shared decision making concerning the development and implementation of a policy or program. In a case like this, the stakeholder group should be made aware of the ways in which its involvement will be reflected in decision making. Making the objectives clear from the start so that expectations are reasonable and accurate can support effective and meaningful engagements.

In addition to offering guidelines for consultations, some departments such as Health Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada have focal points for consultation activities. At Health Canada, the Communications and Public Affairs Branch seeks to integrate national and regional perspectives into all of its policies and strategies, communications and consultation functions. At Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Communication and Consultation Branch is the focal point for research, advice, and coordination of consultations and citizen engagement.

When considering the idea of support for AANDC personnel on engagements, the Department's distinction between consultations triggered by the legal duty to consult and those that are not is critical. At AANDC, the Consultation and Accommodation Unit is an established unit that makes guidance and support on consultations triggered by the legal duty to consult available to departmental staff and to other federal departments and agencies. However, as noted, there is no support system for engagements not associated with the legal duty to consult. One result, as seen among the AANDC personnel interviewed, is confusion and/or disagreement about this distinction. Some recognized that the Department and the federal government distinguish between the two, while others believed that all AANDC engagements are linked to the legal duty to consult.

The apparent divergence is a by-product of the decentralised approach to C & PD engagements coupled with the lack of guidance for engagements not related to the duty to consult. Table 4 (below) provides an explanation of how AANDC distinguishes between engagements triggered by the legal duty to consult and those that are not, but are for good governance and sound development and implementation of departmental policies and programs.

Table 4: The Legal Duty to Consult vs. Engagement for

AANDC Policy and Program Development

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada navigates between two major types of engagement with Aboriginal people. First, there are engagements originating in the legal duty to consult, triggered when Crown conduct may affect Aboriginal or Treaty rights and, second, there are engagement activities for the purposes of good governance and effective AANDC policy and programming. Although there may be a legal distinction between these forms of engagement, both types are key factors in maintaining productive relationships between Aboriginal people in Canada and the federal government.

The 2011 Updated Guidelines for Federal Officials to Fulfill the Duty to Consult, produced by the AANDC Consultation and Accommodation Unit,offers a clear distinction between consultations triggered by the legal duty to consult and those limited to departmental policy and programming objectives.

According to the Updated Guidelines, three factors are required to trigger the legal duty to consult:

- There is proposed Crown conduct;

- The proposed Crown conduct could potentially have an adverse impact on potential or established Aboriginal or Treaty rights; and

- There are potential or established Aboriginal or Treaty rights in the area.

For a duty to consult to exist, all three factors must be present.Footnote 36 Not all engagements between AANDC and Aboriginal peoples occur because the legal duty to consult has been triggered: many occur for reasons such as sound development and implementation of departmental policies and programs that are not, according to the Department, linked to the legal duty to consult.

Recommendation #2

It is recommended that AANDC:

- Provides advice, guidance, and tools to AANDC personnel involved in engagements not triggered by the legal duty to consult and continue to support the flexibility and broad application of the Consultation and Policy Development Authority.

5. Performance

5.1 Achievement of Expected Outcomes

5.1.1 The design and delivery of C & PD as well as its performance reporting does not support a thorough assessment of the achievement of expected outcomes for the C & PD authority.

5.1.2 Engagements conducted through the C & PD authority have generally:

- Contributed to enhanced awareness among AANDC personnel of the positions of Aboriginal peoples with respect to AANDC policy and program agendas;

- Contributed to enhanced awareness among Aboriginal peoples with respect to AANDC policy and program agendas; and

- In some cases, C & PD contributed to enhancing Aboriginal influence on departmental programs and policy.

Design and Delivery of C & PD

As discussed in Design and Delivery, the C & PD authority generally focuses more on conducting core and core like activities, rather than engagement activities that are designed and implemented according to the principles of well run stakeholder consultations. As a result, it was difficult to assess the engagement related outcomes in the authority's logic model beyond forming impressions on the availability of information, and in certain cases, on the types of activities conducted. In some cases though, where the funding was used to conduct more typical engagement activities, the evaluation was able to determine the purpose of the funding as it relates to engagement outcomes and the results of those engagement processes.

Reporting on activities funded through the C & PD authority

The decentralised nature of the C & PD authority management structure contributed to a shortage of performance information on the activities, outputs and impacts associated with C &PD funding over the evaluation period. Although the evaluation team is aware of the rationale for this decentralised structure, it was still necessary to mitigate this information shortfall. The evaluation team constructed a picture of the activities funded through the C & PD authority by analyzing information housed in Grants and Contributions Information Management System and sampling from its collection of funding information and recipient reports. This exploration revealed that some activities funded over the evaluation period were not clearly related to specific engagement initiatives and that recipient reporting varies greatly from one project/recipient to another, undermining the collection of performance information that would speak directly to the achievement of expected results for the C & PD authority.

As would be expected for an authority that is designed to be flexible and used by the entire Department, funds were allocated over a wide range of activity titles and topics. The wide range of topics for engagement is in line with what interviewees said about the need to address emerging issues and to be responsive to the needs of Aboriginal stakeholders and to address priorities. Moreover, the authority's flexibility makes it possible for the Department to obtain Aboriginal perspectives on topics that do not fit under a program-specific authority.