Evaluation of the First Nation Infrastructure Fund

Final Report

Date: April 2014

Project Number: 1570-7/13066

PDF Version (1.591 Mb, 109 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 5. Program Design and Delivery

- 6. Lessons Learned and Best Practices

- 7. Efficiency and Economy

- Annex A - National Priority Funding Evaluation and Measurement Matrix

- Annex B - Evaluation Issues and Questions

- Annex C - FNIF Community Project Sites

- Annex D - Economic Impact Analysis of First Nations Infrastructure Fund

List of Acronyms

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

|---|---|

| CCP |

Comprehensive Community Plan |

| CFMP |

Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| EMAP |

Emergency Management Assistance Program |

| FNIF |

First Nations Infrastructure Fund |

Executive Summary

This evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund (FNIF) was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch in time for consideration of funding renewal and the consolidation of community infrastructure authorities in 2013-2014.

The FNIF, created in 2007-2008, was a $239.4 million targeted fund for proposal-based projects on-reserve under the following categories: solid waste management; energy systems; local roads and bridges; planning and skills development; and connectivity. FNIF funding was scheduled to expire on March 31, 2013, but was renewed under the 2013 budget.

This evaluation builds on the 2010 implementation evaluation and examines the FNIF's relevance, performance and design and delivery from 2007-2008 to 2012-2013. The methodology used to conduct this evaluation included a document and file review; a literature review; 71 key informant interviews with federal government and First Nation representatives, external experts and stakeholders; five case studies; an economic impact analysis conducted by consulting firm Malatest & Associates Ltd.; and participation in a Comprehensive Community Planning workshop.

Key findings and conclusions from the evaluation are as follows:

Relevance:

- The FNIF was established to address long-standing infrastructure funding needs that continue to exist in First Nation communities.

- FNIF funding categories continue to be consistent with the objectives and priorities of the federal government and First Nation communities.

- Providing funding for community infrastructure development on reserve is a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government.

- The division of roles and responsibilities of AANDC and Infrastructure Canada was appropriate and while initially necessary, Infrastructure Canada's involvement would not be required under a renewed FNIF.

Performance:

- Evidence suggests that the FNIF was a high impact fund because the projects were relatively small, numerous and representative of community priorities. Key impacts of FNIF projects include: safer roadways and bridges; environmental and health benefits from reduced burning of garbage; improved energy security and reduced reliance on diesel; improved First Nations' infrastructure management and technical capacity to maintain infrastructure; and improved delivery of public/government services, including e-education, e-health and remote water monitoring.

- Though unexpected, community-driven Comprehensive Community Planning projects resulted in healing transformations, the prevention of third party management, and the improvement of relationships with municipal, provincial and federal governments.

- Completed FNIF projects provided communities with tangible results that sparked momentum for communities to engage in additional initiatives and identify unexpected opportunities for economic development.

- The FNIF proposal-based program design posed numerous challenges which could be mitigated by incorporating FNIF project proposals into the Department's annual National Capital Planning Process and strengthening the priority ranking criteria of the First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan's "Community Infrastructure" component.

- Completed FNIF projects put pressure on the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (CFMP) budget as it funds their operations and maintenance support. Additionally, completed infrastructure projects are rarely operated and maintained for optimal infrastructure sustainability.

- Performance Measurement is a continuing challenge for infrastructure programming. There is a need for a concerted effort to rectify the shortfalls of the Information Technology tracking applications to encourage their consistent use.

- Regional inflation limited the amount of projects that could be funded in provinces experiencing significant economic growth as costs were high and contractors were few.

- Technical expertise for supporting project designs and construction oversight was not always readily available, which in some cases left First Nations vulnerable to overpricing and poor design from contractors and consultants.

Lessons Learned and Best Practices:

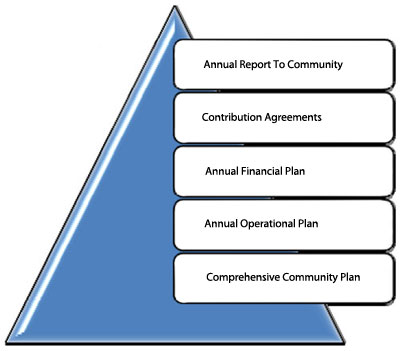

- FNIF funded Comprehensive Community Plans have been growing in popularity and utility as a result of emerging best practices such as the use of Comprehensive Community Plan champions, First Nation to First Nation mentorship components, British Columbia region's annual workshop, and extensive community engagement.

- Strategic relationships with University Planning and Engineering Departments has allowed for important partnerships when designing and implementing infrastructure projects.

- FNIF projects that invested highly in building the knowledge and skills of First Nation community members have supported career development and not just temporary employment for First Nation communities.

- It was found that local ownership and management of internet infrastructure yields cost savings and employment benefits especially for remote communities.

Efficiency and Economy:

- The FNIF was able to leverage a significant amount of funds that expanded its impact. The cost-sharing component should thus be encouraged moving forward but with caution as cost-sharing may put low-capacity and remote First Nations at a disadvantage.

- FNIF was able to apply a Public, Private Partnership model for funding connectivity projects in that multiple communities were connected under a single project and contractor. This approach was found to be efficient and could be more broadly applied to funding common infrastructure projects for multiple First Nation communities.

- The regional delivery method of using existing CFMP human resources to implement FNIF projects was found to be the most effective and efficient approach.

- The pressure to select the lowest cost when infrastructure projects are put to tender was found to be an inefficient policy. There is a need to analyze and improve the Community Infrastructure Branch's tendering policies based on identified regional best practices.

- Opportunities exist for improved departmental programming collaboration in the areas of community planning, disaster mitigation, completing energy feasibility studies, and engaging in infrastructure and physical land use planning to support economic development.

It is therefore recommended that AANDC's Community Infrastructure Branch:

- Examine the feasibility of integrating the call for FNIF project proposals into the Department's annual Capital Planning application process.

- Expand existing management and oversight documents to ensure funded projects include: (a) identification of operations and maintenance funding sources that adequately meet the life-cycle cost of the asset; (b) identification of necessary training requirements; (c) disaster mitigation infrastructure design elements; and (d) an expanded eligible recipients list to allow for more flexible partnerships with the private sector, academia and Aboriginal organizations.

- Engage the Professional and Institutional Development Directorate to (a) identify practical ways for Professional and Institutional Development to support community planning projects funded under the Planning and Skills Development category; and (b) to develop a strategy to align the Department's community planning and support activities.

- Review the program's tendering policy and best practices across the regions to ensure an effective and consistent approach nationally.

- Engage ecoENERGY in order to identify a strategy for sharing completed feasibility studies to support potential FNIF-funded energy projects and ensure information is accessible to regional front-line officers.

Management Response / Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund

Project #: 1570-7/12024

| Recommendations | Response and Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. It is recommended that the Community Infrastructure Branch examine the feasibility of integrating the call for FNIF project proposals into the Department’s Annual Capital Planning process. | The Community Infrastructure Branch is integrating the call for FNIF project proposals into the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program Annual Capital Planning Process. | Scott Stevenson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister- Regional Operations | April 2014 |

| 2. It is recommended that the Community Infrastructure Branch expand existing management and oversight documents to ensure funded projects include: (a) identification of operations and maintenance funding sources that adequately meet the life-cycle cost of the asset; (b) identification of necessary training requirements; (c) disaster mitigation infrastructure design elements; and (d) an expanded eligible recipients list to allow for more flexible partnerships with the private sector, academia and Aboriginal organizations. | The Community Infrastructure Branch is expanding program oversight to ensure that funded projects include:

|

Scott Stevenson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister- Regional Operations | Fall 2014 - Winter 2015 |

| 3. It is recommended that the Community Infrastructure Branch engage the Professional and Institutional Development Directorate to (a) identify practical ways for Professional and Institutional Development to support community planning projects funded under the Planning and Skills Development category, and (b) to develop a strategy to align the Department’s community planning and support activities. | The Community Infrastructure Branch is working with Professional and Institutional Development to develop a strategy to align the Department’s community planning and support activities. | Scott Stevenson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister- Regional Operations | Fall 2014 |

| 4. It is recommended that the Community Infrastructure Branch review the program’s tendering policy and regional best practices to ensure an effective and consistent national approach. | The Community Infrastructure Branch is reviewing the program’s tendering policy and regional best practices to ensure a consistent national approach and comparability to practices off reserve. | Scott Stevenson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister- Regional Operations | Fall 2014 |

| 5. It is recommended that the Community Infrastructure Branch engage ecoENERGY in order to identify a strategy for sharing completed feasibility studies to support potential FNIF-funded energy projects and ensure information is accessible to regional front-line officers. | The Community Infrastructure Branch will engage with the Climate Change Division's ecoENERGY in order to identify how best to use the information received from the technical and strategic advisory services they contracted and access and/or share feasibility studies to support potential FNIF-funded energy projects and ensure information is shared to regional front-line officers. | Scott Stevenson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister- Regional Operations | Fall 2014 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on January 28, 2014, by:

Michel Burrowes

Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response / Action Plan

Original signed on January 28, 2014, by:

Scott Stevenson

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on February 6, 2014.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This summative evaluation of the First Nations Infrastructure Fund (FNIF) was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation and in time for consideration of funding renewal and the consolidation of community infrastructure authorities in 2013-2014 into the Contributions to Support Construction and Maintenance of Community Infrastructure. The evaluation builds on the 2010 implementation evaluation and examines the FNIF's relevance, design and delivery and performance from 2007-2008 to 2012-2013. The evaluation was conducted by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC).

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

In 2007, AANDC and Infrastructure Canada entered into an agreement to invest $127.3 million over five years for on-reserve infrastructure projects. The FNIF funding was pooled from three pre-existing federal sources: Infrastructure Canada's Municipal Rural Infrastructure Fund, the Gas Tax Fund, and AANDC's Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program (CFMP). In Budget 2007, AANDC accessed an additional $107.6 million from Infrastructure Canada's Building Canada Fund and in 2009, this was used to increase the total FNIF contributions envelope to $234.9 million; at this point connectivity was also added to the existing suite of investment categories. The targeted fund was proposal-based and was intended to address long-standing community infrastructure needs that had not been funded under existing infrastructure programming.

FNIF funding was scheduled to expire on March 31, 2013, but was renewed under the 2013 Budget. Over the next five years, just under $139 million of the renewed Gas Tax Fund was set aside for FNIF funding; Gas Tax funding is statutory and can be re-adjusted every five years based on First Nations' population on reserve.Footnote 1 Additionally, as part of Canada's Economic Action Plan 2013, a further $155 million over ten years from the New Building Canada Fund was set aside for the FNIF.Footnote 2

1.2.2 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

According to the FNIF Terms and Conditions (2007), the fund specifically seeks to:

- improve the health and safety of First Nation communities;

- contribute to a cleaner and healthier environment;

- improve the delivery of public/government services, including education and e-health to First Nation communities; and

- enhance collaboration among First Nation communities, municipalities, provinces and the Government of Canada.

To reach its strategic outcomes, the FNIF provided funding in five project categories:

- Solid waste (management): construct, restore and improve infrastructure that improves solid waste management and increases the recovery and use of recycled and organic materials, reduces per capita tonnage of solid waste sent to landfill, reduces environmental impacts and enhances energy recovery.

- Energy systems: construct, restore or improve local band-owned infrastructure that optimizes the use of energy sources (e.g., in buildings and other installations), accesses provincially owned energy grids and reduces the greenhouse gas emissions and air contaminants arising from local sources.

- Local roads and bridges: 1) construct, restore or improve public roads and bridges that will result in improved safety, support tourism and commerce, support social and economic development of local areas; and 2) reduce the need for client travel outside of their local region for schooling and healthcare purposes.

- Planning and skills development: to support investment in community planning and/or skills development projects that will support long-term sustainable community development of First Nation communities.

- ConnectivityFootnote 3: to support under-connected First Nations to gain access to regional broadband network expansions driven by regional, provincial, and private sector broadband infrastructure partnerships in order to improve social, cultural and economic development opportunities, as well as: improve the delivery of public services, such as government services, education, and e-health to First Nation communities.

The fund's performance measurement strategy is contained under the umbrella of the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program's 2009 Performance Measurement Strategy. FNIF Performance Indicators include:

- The Community Well-Being index, developed by AANDC's Research and Analysis Directorate

- Percentage of communities able to undertake basic public works activities

- Estimated reductions in greenhouse gas emissions

- Percentage of First Nation communities with electricity/power generation in fair or better conditions

- Percentage of First Nation communities that are off-grid

- Percentage of roads and bridges with a fair or better condition rating

- Percentage of First Nation communities with access to broadband connectivity

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

AANDC was responsible for program delivery, performance measurement, and reporting annually to Infrastructure Canada and to Parliament on the program's progress. The two departments jointly designed the terms and conditions, a Memorandum of Understanding, and the development of a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework. A National Oversight Committee with representatives from both departments monitored the FNIF's progress.

Eligible applicants included:

- First Nation governments, including a band or tribal council or its agent (wholly-owned corporation), on the condition that the First Nation has indicated support for the project and for the legally designated representative to act as an applicant through a formal band or tribal council resolution; and

- Innu communities where the applicant is on reserve, Crown land in the province.

FNIF funding did not extend to communities in the territories as funding was disseminated by the respective territorial governments.

1.2.4 Infrastructure Investment Decision Making

AANDC's CFMP funds the majority of infrastructure projects on reserve and determines funding priorities using the National Capital Planning Process. This process includes three layers of annual planning: (1) A community level plan is submitted by each First Nation to the AANDC regional office detailing their infrastructure needs; (2) The regional office develops their Capital Plan indicating planned program expenditures; and (3) The First Nations Infrastructure Investment Plan is then developed based on each Regional Capital Plan to provide a strategic overview of national CFMP investment decisions.

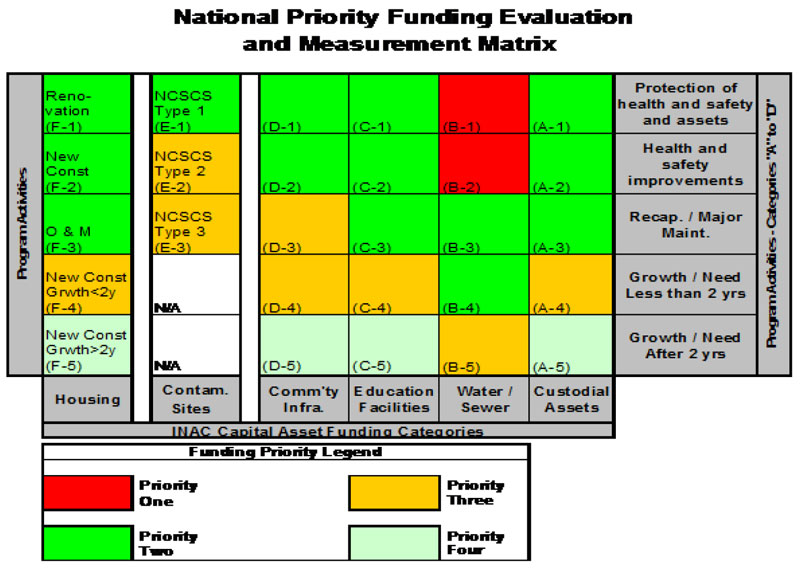

Projects are prioritized at the regional level using the National Priority Funding Evaluation and Measurement Matrix (available in Annex A), which includes six columns ranked in order of priority. Within these columns, projects are ranked on a scale of 1-5 depending on their priority level. Projects that impact the health and safety of the community receive the highest ranking while projects that address community growth and future needs receive the lowest ranking. Column D, "Community Infrastructure" includes several of the FNIF funding categories and is ranked lowest in terms of priority. However, funding decisions for the FNIF were not based on this process but instead on a separate proposal submission process where projects were ranked by regional selection committees using FNIF mandatory screening criteria and the selection criteria for specific project categories, in consideration of local needs and priorities.

1.2.5 Program Resources

In total, AANDC invested $240,744,000 in contributions under the FNIF while sourcing an additional $21,423,500 in other departmental funds (Table 1). The FNIF funding was divided amongst AANDC's seven regional offices south of 60̊ on a per capita basis weighted with levels of remoteness (Table 2). Additional project funding from other partners and stakeholders totaled approximately $241,467,113 (Table 1). A total of $2,177,320 was provided for internal AANDC program operating costs (Table 3).

These investments amounted to a total of 434 funded projects from 2007-2013 (Table 1) representing 35 percent of the 1,242 project proposals received. The remaining 808 project proposals either remain unfunded or have been included as lower priorities on Regional Capital Plans, which will likely not be funded by the CFMP.

| FNIF Category | # of projects | 07/08 | 08/09 | 09/10 | 10/11 | 11/12 | 12/13 | Total FNIF Investment |

(A-base)Footnote 4 | Other Funding SourcesFootnote 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | 20 | 0 | 0 | 9,038,310 | 5,833,753 | 16,704,282 | 10,490,473 | $42,066,818 | 1,201,209 | 150,499,543 |

| Energy Systems | 41 | 860,781 | 4,124,945 | 377,881 | 1,622,104 | 2,336,794 | 2,609,021 | $11,931,526 | 121,980 | 29,256,122 |

| Planning and Skills Development | 50 | 1,283,447 | 6,871,222 | 1,998,597 | 2,376,437 | 3,017,616 | 2,206,740 | $17,754,059 | 1,032,470 | 5,073,101 |

| Roads & Bridges | 142 | 4,184,873 | 26,994,689 | 25,665,738 | 22,881,229 | 36,010,942 | 21,699,220 | $137,436,691 | 17,034,365 | 51,284,993 |

| Solid Waste Management | 81 | 813,499 | 3,607,448 | 3,100,654 | 1,680,492 | 10,191,244 | 12,161,248 | $31,554,585 | 2,033,489 | 5,353,354 |

| TOTAL | 434 | $7,142,600 | $41,598,304 | $40,181,180 | $34,394,015 | $68,260,878 | $49,166,702 | $240,743,679 | $21,423,513 | $241,467,113 |

| Region | # of projects | 07/08 | 08/09 | 09/10 | 10/11 | 11/12 | 12/13 | Total ACTUALS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 17 | 147,000 | 4,154,952 | 0 | 914,115 | 2,470,375 | 2,529,511 | $10,215,953 |

| Quebec | 52 | 1,806,206 | 4,794,038 | 1,451,724 | 2,554,206 | 12,669,034 | 6,024,935 | $29,300,143 |

| Ontario | 82 | 986,307 | 11,252,624 | 6,527,605 | 3,519,164 | 14,109,897 | 5,646,905 | $42,042,502 |

| Manitoba | 58 | 2,237,875 | 5,328,296 | 10,309,411 | 10,136,031 | 11,151,469 | 8,430,686 | $47,593,768 |

| Saskatchewan | 31 | 0 | 4,389,800 | 14,112,500 | 8,847,900 | 7,687,400 | 8,318,500 | $43,356,100 |

| Alberta | 45 | 490,689 | 3,118,771 | 5,174,580 | 5,104,014 | 9,581,542 | 10,220,670 | $33,690,266 |

| British Columbia | 149 | 1,474,523 | 8,559,823 | 2,605,360 | 3,318,585 | 10,591,161 | 7,995,495 | $34,544,947 |

| TOTAL | 434 | $7,142,600 | $41,598,304 | $40,181,180 | $34,394,015 | $68,260,878 | $49,166,702 | $240,743,679 |

| Resource Category | 07/08 | 08/09 | 09/10 | 10/11 | 11/12 | 12/13 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AANDC SALARY Total | 181,756.66 | 306,847.87 | 328,554.22 | 265,370.27 | 370,219.31 | 173,427.18 | 1,626,175.51 |

| AANDC NON SALARY Total | 9,002.23 | 127,676.81 | 39,695.38 | 49,028.95 | 53,591.50 | 1,519.17 | 280,514.04 |

| NON BUDGETARY Total | 30,315.40 | 49,734.01 | 58,679.46 | 46,317.46 | 57,465.33 | 28,116.21 | 270,627.87 |

| Grand Total | 221,074.29 | 484,258.69 | 426,929.06 | 360,716.68 | 481,276.14 | 203,062.56 | 2,177,317.42 |

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined program relevance, design and delivery and performance over the entirety of the fund’s existence from 2007-2008 to 2012-2013. Evaluation Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC’s Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 21, 2013. Field work was conducted between July and October 2013.

2.2 Evaluation Issues

Aligned with Treasury Board requirements, the evaluation focused on the following issues (Refer to Annex B for Evaluation Questions):

Relevance

Continued Need

Alignment with Government Priorities

Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Performance

Effectiveness

Demonstrations of Efficiency and Economy

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The following section outlines the evaluation’s data collection methods, major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report and processes undertaken for quality assurance.

2.3.1 Data Sources

Literature Review

The literature review was used to examine broader trends, issues and challenges related to municipal infrastructure development and financing, as well as its linkages to economic development and social, health and environmental well-being for communities in the Canadian context. The literature review also concentrated on the necessity of funding infrastructure based on comprehensive community planning practices.

Document and File Review

The document review looked at internal (FNIF) documents such as previous FNIF audits, evaluations, management responses and action plans; previous and current related program evaluations and reports; program reports; project tracking files; external reports and communications; program operational documents (e.g., Results-based Management and Accountability Frameworks, Performance Measurement Strategy, operational plans, strategic plans, AANDC quarterly reporting); and public communications.

Key Informant Interviews

Seventy-one stakeholders and experts were interviewed, including eight program staff at Headquarters; eight additional Headquarters stakeholders; nine external experts and stakeholders; two National Oversight Committee members; two federal partners; and 42 regional AANDC staff members. First Nation recipients and community members were interviewed as part of the case studies and as such, were not included in the total number of Key Informant Interviews.

Case Studies

Five case studies were completed in total, one for each of the funding categories eligible under the FNIF. The case studies included four data collection methods: site visits (or video conferencing when more efficient); focus groups with First Nation project teams; focus groups with targeted community members operating or using the infrastructure developed; and a review of reporting documents from recipients.

The following communities and partners were visited based on four criteria: (1) total project costs; (2) number of projects approved for a community; (3) regional representation; and (4) recommendations from regional offices. In total, the case studies included 46 stakeholders (project details available in Annex C).

| Communities and Project Sites | AANDC Region |

|---|---|

| Solid Waste Case Study | |

| Whitecap Dakota First Nation | Saskatchewan |

| Peguis First Nation | Manitoba |

| Roads and Bridges Case Study | |

| Poplar River First Nation | Manitoba |

| Fisher River Cree Nation | Manitoba |

| Whitefish Lake First Nation | Alberta |

| Planning and Skills Development Case Study | |

| Musqueam Indian Band | British Columbia |

| Penticton First Nation | British Columbia |

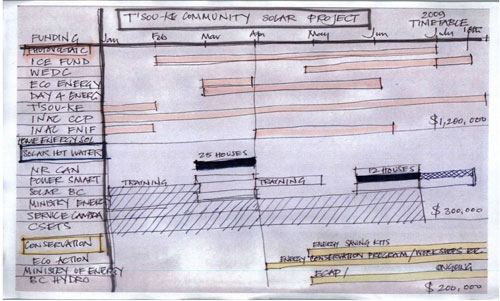

| T’Souke First Nation | British Columbia |

| Saddle Lake Cree Nation | Alberta |

| Energy Systems Case Study | |

| Kitasoo | British Columbia |

| Gitga’at First Nation | British Columbia |

| T’Souke First Nation | British Columbia |

| Connectivity Case Study | |

| Alberta Supernet/First Nations (Alberta) TechnicalServices Advisory Group Connectivity Project | Alberta |

| Nishnawbe Aski Nation | Ontario |

| Conseil en Éducation des Premières Nations | Quebec |

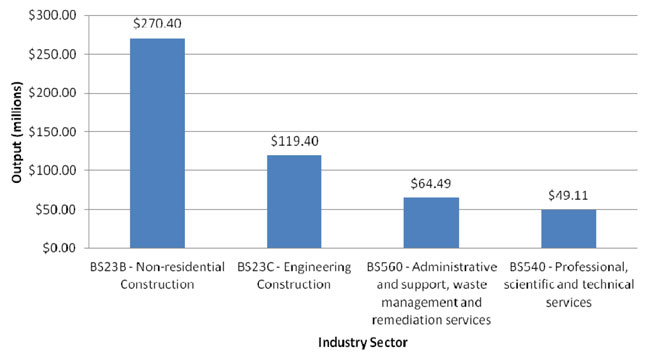

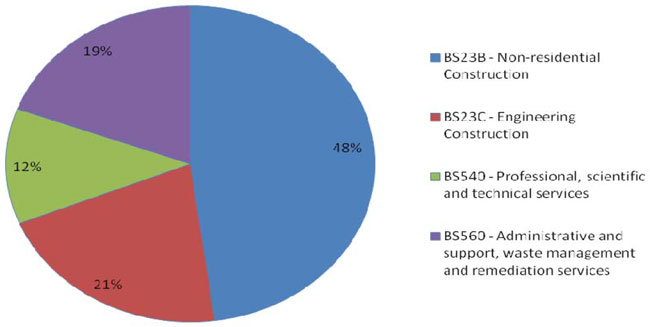

Economic Impact Analysis

The consulting firm Malatest & Associates Ltd. used regional records of funding decisions and a project tracking database alongside provincial input-output multipliers developed by Statistics Canada to estimate the return on investment of FNIF-funded projects. Estimated results included total output generated, contribution to Canadian gross domestic product (GDP), total income generated through employment and total number of jobs created.

Comprehensive Community Planning Workshop

The evaluation team attended British Columbia’s Annual Comprehensive Community Planning (CCP) Workshop co-hosted by Little Shuswap Lake Indian Band and AANDC from October 1-3, 2013. Over 100 attendees representing 50 First Nation communities participated in the workshop. Key note speakers from First Nations implementing their CCPs shared their stories and provided practical workshops on topics such as: Finding the support you need to get started; Engaging community members; Monitoring and evaluating planning progress; Integrating CCP with other planning processes; Indigenous planning as a healing process; and Keeping the plan alive. Through presentations, break-out groups and informal discussions, the evaluation team spoke with a large sample of First Nation representatives, regional staff and external stakeholders about the First Nation community planning process, including key challenges and best practices.

2.3.2 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Where possible, the evaluation team collaborated with other Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch case study travel for purposes of cost-efficiency.

The main limitation in the evaluation process was a lack of readily available program performance information for analysis. The Integrated Capital Management System was not fully operational during the implementation of the FNIF due to an ongoing review of the system’s performance, and still remains a challenge for some regions that are just now populating the system with completed project data. As such, evaluators could not obtain precise numbers on how many communities benefitted from FNIF funding.

In response to the 2010 implementation evaluation, the program designed performance indicators such as the percentage of communities with roads and bridges or electrical/power generation in fair or better conditions; however, inspections operate on a three year cycle and many FNIF projects have not yet had their first reviews.Footnote 8 As a result, evaluators could not obtain usable performance data. It is expected that these concerns will be addressed through the development of the Infrastructure and Capacity Performance Measurement Strategy currently underway as part of the Performance Measurement Strategy Action Plan for 2013-2014.

The 2010 implementation evaluation of the FNIF was undertaken at the same time as an evaluation of the CFMP; this was due to overlapping design and delivery issues and a desire to reduce the reporting burden for regional offices and First Nation communities by amalgamating the interviews, focus groups and site visits. This approach of timing evaluation work under Section 2.4 of the 2014-2015 Program Alignment Architecture should be continued for future evaluation work as the FNIF evaluation results also pertained to funding water and wastewater, education facilities, housing, renewable energy, emergency management assistance and other community infrastructure.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch of AANDC’s Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority responsible for completing the evaluation. Quality assurance activities were put in place to preserve the quality of the data and ensure that the methodology selected was appropriate. These mechanisms included:

- Internal peer-review process at the AANDC Evaluation Branch: Two members of the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch not affiliated with the current evaluation reviewed the evaluation for issues with methodology, data collection and interpretation.

- The evaluation working group: This group, headed by the evaluation manager, was made up of AANDC and Infrastructure Canada program representatives, including regional program managers and two representatives from a Tribal Council that received FNIF funding. The group was responsible for reviewing, validating and commenting on the choice of methodology, the preliminary findings and the final report.

- The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee: This committee is made up of the Chief Financial Officer, the senior assistant deputy ministers and external experts. It is headed by the Deputy Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. It was responsible for approving the evaluation’s Terms of Reference, preliminary findings report, the final evaluation report and Management Response and Action Plan.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

3.1 Continued Need

The FNIF was established to address long-standing infrastructure funding needs that continue to exist in First Nation communities.

Original Need for the FNIF

AANDC funds infrastructure development on reserve based on the national infrastructure ranking process outlined in Section 1.2.4. In practice, this means that the majority of AANDC's infrastructure funding must be allocated to water and wastewater systems, education facilities and housing. Often, available funding does not cover the expanse of needs within these categories. Furthermore, much of the CFMP funding comes from targeted sources like the First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan, which could not be used for community infrastructure even if it were higher on the priority list. AANDC has individual programs for housing and contaminated sites whereas all other types of infrastructure assets and their operations and maintenance requirements fall under the CFMP. CFMP funding is further strained when it must be regularly re-profiled towards addressing statutory obligations such as education, social programming and other priorities. These funding constraints are significant as they make it difficult for community infrastructure priorities to be addressed.

The majority of internal key informants corroborated these concerns by explaining that the strained CFMP budget means other community infrastructure projects cannot be funded. These views corroborate concerns expressed by First Nation community interviewees that there has been a long-standing need to fund community infrastructure such as solid waste management and roads and bridges.Footnote 9 The SchoolNet evaluation noted that e-learning, video conferencing and other connectivity-related opportunities were not realistic for First Nations without specific targeted investments.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the evaluation of the CFMP called for a targeted program to fill in these gaps,Footnote 11 and the implementation evaluation of the FNIF found that it closely mirrored the needs expressed by communities.Footnote 12

AANDC's limited ability to fund community infrastructure is exacerbated by a lack of external options for financing in First Nation communities.Footnote 13 The 2011 Evaluation of Implementation of the First Nation Fiscal and Statistical Management Act found that governments use their infrastructure and services to stimulate their economy through industrial, commercial, and residential development in their jurisdictions; however, First Nation communities have faced sizeable challenges in funding infrastructure needs in large part because there is no formal framework under the Indian Act to support the functions of comptrollership, compliance, taxation, and standard-setting that would facilitate First Nation governments gaining affordable access to capital markets.Footnote 14 While support for infrastructure in Canada is also typically financed through external loans,Footnote 15 securing access to finances is often difficult for First Nation communities given that financing tends to be limited to borrowers already established in the economy.Footnote 16Furthermore, relevant literature revealed that a lack of adequate infrastructure is one of many factors influencing the pace and success of economic development ventures on reserve.Footnote 17

Limited alternatives to funding infrastructure on reserve include the First Nations Finance Authority, which provides low-cost loans to First Nations registered under the First Nations Fiscal Management Act. The Act provides communities with the capacity to collect taxes and ensures accountability to taxpayers by supporting the development of financial management capacity; regulatory oversight is provided for First Nations that are exercising jurisdiction over the collection of property taxes and accessing loans through a pooled borrowing regime. Additionally, the Royal Bank of Canada's Aboriginal Partnerships Program provides funding to promote Aboriginal economic development and has invested $12 million into roads and bridges to date.Footnote 18

An analysis conducted by the GBC Group in 2011 suggests that the challenge of funding infrastructure development is typical for many small or remote Canadian communities. These communities (1) tend to rely on provincial and federal grants; (2) do not tend to access private financial institutions; and (3) will use own-source revenue for funding the operations and maintenance of assets but not for construction of assets.Footnote 19 These findings corroborate the 2010 program evaluations of the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program and the FNIF, which demonstrated that the FNIF was an essential program for developing infrastructure on reserve, and that until First Nation communities are able to develop their own-source funding revenue streams, major capital infrastructure needs will go unaddressed in the absence of federal funding.Footnote 20

Ongoing Need for the FNIF

Originally, the FNIF was a small targeted fund of just over $240 million. Of the 1,242 proposals received, 808 remained unfunded at the end of the third call, amounting to $689 million of eligible unfunded projects. The vast amount of eligible unfunded projects demonstrates that there is a continuing demand for the fund that expired in March 2013. The ongoing need for a similar funding source will be fulfilled by the New Building Canada Plan announced in the 2013 Federal Government Budget in addition to ongoing Gas Tax funding.Footnote 21

Communities' highest requests under the FNIF were for the Planning and Skills Development category and the Roads and Bridges category. Roads and Bridges was also the largest funded category at $137,436,691, representing over 57 percent of the fund. The continued need for funding roads and bridges was also identified in Infrastructure Canada's evaluation of its First Nations Infrastructure componentFootnote 22 and by the majority of case study interviewees. Roads and bridges were a priority for First Nation communities looking to: (1) increase their access to external resources; (2) improve the look and feel of their communities for community morale; and (3) entice potential investors. The 2010 evaluation of the CFMP also argued that supporting provincial and territorial access roads to First Nation communities is a vital factor in supporting health and safety as well as economic development.Footnote 23

On March 21, 2013, the Honourable Jim Flaherty, Minister of Finance, announced additional funding for the FNIF as part of Budget 2013. The findings above demonstrate this renewal responds to the needs - and typically unfunded priorities - of communities identified in this evaluation.

3.2 Alignment with Federal Government Priorities, Departmental Strategic Outcomes, and First Nations' Priorities

FNIF funding categories continue to be consistent with the objectives and priorities of the federal government and First Nations communities.

Alignment with Federal Government Priorities:

The FNIF was found to be consistent with a long-standing priority of the Government of Canada regarding infrastructure investment:

- In the 1999 Speech from the Throne, the Government outlined its intention to "make a long term contribution towards a dynamic economy through the building of infrastructure."Footnote 24

- In Budget 2000, $2.05 billion was allocated over six years to improving urban and rural infrastructure.Footnote 25

- The 2002 Speech from the Throne pledged to put in place a ten year initiative of infrastructure renewal.

- Budget 2003 confirmed this commitment by providing $1 billion to help meet the infrastructure needs of smaller communities.Footnote 26

- Budget 2006 committed to providing stable and reliable funding to provinces, territories and communities to help them meet their infrastructure needs.Footnote 27

More recently, the Government has made significant investments in infrastructure through three sources: the Gas Tax Fund, the Building Canada Fund and through additional Economic Action Plan stimulus funds. The Gas Tax Fund was originally intended to provide $5 billion to municipalities over five years; however, in 2007 the fund was extended with the annual amount increased to $2 billion, and on December 15, 2011, the fund was legislated to be a permanent annual infrastructure investment. The Building Canada Fund was announced in the 2007 Speech from the Throne and provided $8.8 billion for national, regional and local infrastructure priorities from 2007-2014. Furthermore, the 2013 Speech from the Throne noted that infrastructure investment "contributes in a fundamental way to growth and long-term prosperity"Footnote 28 and thus, a new Building Canada Fund was established that, when combined with other federal infrastructure investments, will result in $70 billion in infrastructure funding over 10 years - the largest long-term commitment to infrastructure in Canadian history.Footnote 29 The size and consistency of infrastructure investments over time demonstrates the priority placed on infrastructure development by the Government of Canada.

In terms of infrastructure investments on reserve, Budget 2006 announced "A New Approach" to helping Aboriginal communities, which sought to reduce disparities between Aboriginal people and other Canadians.Footnote 30 Canada's Economic Action Plan stimulus funding provided $515 million over two years for "ready-to-go" First Nations infrastructure projects in priority areas, including schools and water. Additionally, Budget 2013 made significant investments in First Nations infrastructure, including $7 billion over ten years for "roads, bridges, energy systems and other First Nations infrastructure priorities".Footnote 31

At the departmental level, AANDC supports infrastructure investment on reserve through its Land and Economy strategic area with the expected ultimate outcome of "full participation of First Nations, Métis, Non-Status Indians and Inuit individuals and communities in the economy."Footnote 32 Specifically, AANDC supports a suite of Infrastructure and Capacity programming where FNIF works to support the long-term expected result that "First Nation communities have a base of infrastructure that protects health and safety and enables engagement in the economy."Footnote 33 The FNIF, therefore, aligns with these departmental priorities by providing a base of community infrastructure that supports health and safety while also laying the foundations for economic development.

In the 2012-2013 AANDC Report on Plans and Priorities, the Department identified eleven priority areas that fall under three themes. Several of the FNIF funding categories are designed to help meet these priorities.Footnote 34 Specifically, under the "Transforming for Improved Results" theme, the priority of "Improving Economic Development and Sustainability"Footnote 35 was identified. The FNIF supports this priority by undertaking infrastructure projects that will spur economic development in First Nation communities or enable community members to access nearby economic/employment opportunities. Furthermore, the theme "Improving Partnerships and Relationships" includes the priority "Facilitate Community Development and Capacity."Footnote 36 The 2012-13 Departmental Performance Report notes that the Department has worked to achieve this priority by "advancing the Community Development Framework and related tools,"Footnote 37 which include comprehensive community planning. Finally, the 2012-13 Departmental Performance Report states that "connectivity is essential to support Aboriginal online services such as e-commerce, e-learning, remote banking, e-health and online program reporting."Footnote 38 Additionally, the report states that "sound roads and bridges are essential elements of community infrastructure."Footnote 39 As such, the projects funded by the FNIF, through their contributions to community planning and/or economic development, have contributed to the achievement of AANDC departmental priorities.

Alignment with First Nations Priorities:

The evaluation of the CFMP noted that "whereas water projects are given top priority and are well handled with the CFM program…water might not be the highest priority in all communities. Thus, projects such as solid waste management, and roads and bridges may not have received funding."Footnote 40 Additionally, the evaluation noted that capital projects, such as road and bridge construction, have received minimal program support because they fall lower on the national priority list. For First Nations that did not have problems related to water, other projects deemed to have high local priority were often delayed.Footnote 41 While minor capital funding can be used to address these projects where they are eligible, often they go unaddressed when there is not enough funding available.

The FNIF plays a critical role in addressing First Nations infrastructure priorities that do not receive CFMP funding. According to key informants from AANDC Headquarters, AANDC regional offices, the Assembly of First Nations, First Nations organizations and the case studies conducted in First Nation communities, the FNIF funding categories remain relevant and priority areas for First Nation communities across the country as they address long-standing community infrastructure priorities. Additionally, the targeted nature of the FNIF also allows for flexibility in funding project categories in recognition of the range of infrastructure pressures on First Nation communities. As a result, community member interviewees spoke highly of the fund, and with the fund's renewal announcement, are keen to start addressing the additional items on their long-standing Capital Plans.

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

There is a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government in providing funding for community infrastructure development on reserve.

The provision of community infrastructure funding to First Nations is based on the Government of Canada's spending power as a matter of social policy. In particular, the Indian Act gives the Minister the authority to determine whether roads and bridges are of an acceptable condition and to take action if deemed unacceptable.Footnote 42 As such, the FNIF supports AANDC's established role in the support of community infrastructure at the regional level, which can be provided through formula or proposal-based project funding or as a combination of both. The FNIF specifically supports the Department's mandateFootnote 43 by improving the quality of life and the environment for First Nations by assisting communities on reserve, Crown Land or land set aside for the use and benefit of a First Nations within the provinces of Canada to improve and increase public infrastructure.

The division of roles and responsibilities of AANDC and Infrastructure Canada was appropriate and while initially necessary, Infrastructure Canada's involvement would not be required under a renewed FNIF

The Office of Infrastructure Canada leverages the resources and capacities of various departments to deliver infrastructure funding in all provinces, territories and to on-reserve First Nations. With the launch of the Gas Tax Fund in 2005, Infrastructure Canada and AANDC jointly requested the authority to develop the FNIF to pool the resources of the Gas Tax Fund, the Municipal Rural Infrastructure Fund and existing AANDC resources. To jointly oversee the implementation of the fund, regional selection committees, chaired by the Associate Regional Director General for AANDC, were established to identify regional priorities, evaluate project funding applications and then report to the National Oversight Committee made up of AANDC and Infrastructure Canada senior officials on project recommendations and application processing improvements. The partnership - solidified through a Memorandum of Understanding - was intended to leverage AANDC's history, expertise, capacity, and its federal jurisdiction in delivering Infrastructure Canada funding to First Nations and to serve as an exchange of best practices.

The 2010 evaluation noted that roles, responsibilities and accountabilities were generally clear and well-understood.Footnote 44 Key informants have noted that as of 2010, the issues raised at the National Oversight Committee were largely informational items not requiring decision making or the provision of a strategic outlook. This decline in relevancy and frequency of meetings reflected AANDC's full authority over the delivery of the program. Interviewees noted that the inter-departmental relationship is such that Infrastructure Canada, although willing to offer advice, no longer needs to be involved in program implementation as the expertise in delivering the fund resides in the AANDC Headquarters-Regional Office relationship, rather than through an Infrastructure Canada-AANDC partnership. Case study interviewees also noted that it is appropriate for AANDC to administer the fund moving forward and that although the National Oversight Committee is not an efficient entity and no longer needs to operate, the stakeholders from the Committee should continue to be updated and engaged when necessary on infrastructure development on reserve.

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

4.1 Effectiveness

Evidence suggests that the FNIF was a high impact fund because the projects were relatively small, numerous and representative of community priorities.

FNIF projects helped to improve community access, road safety, air quality, community pride and increased environmental protection. As a result, FNIF projects had significant benefits for residents and created employment and investment opportunities for the community as a whole.

Literature review, interviews and case studies all confirmed that the FNIF categories were effective investment opportunities. The literature review specifically found that the FNIF categories are the key building blocks for economic development: A Canada West Foundation 2013 study found that energy, communications and transport systems are the most effective infrastructure investments as a form of economic input.Footnote 45 Vytautas Snieska and Ineta Simkunaite's literature review found that transportation and communication infrastructure lower production costs, expand market opportunities and lead to economic growth.Footnote 46 Adam Brenneman and Michael Kerf argue that transportation networks (including roads and bridges), energy systems, and connectivity dramatically contribute to well-being and productivity (accessible job opportunities, affordable products, and improved education outcomes), all of which contribute to gross domestic product and poverty reduction.Footnote 47

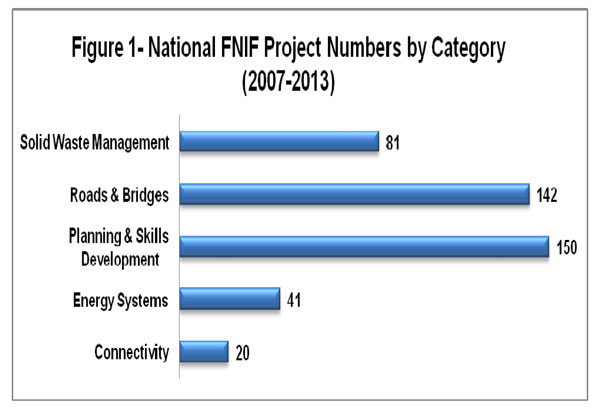

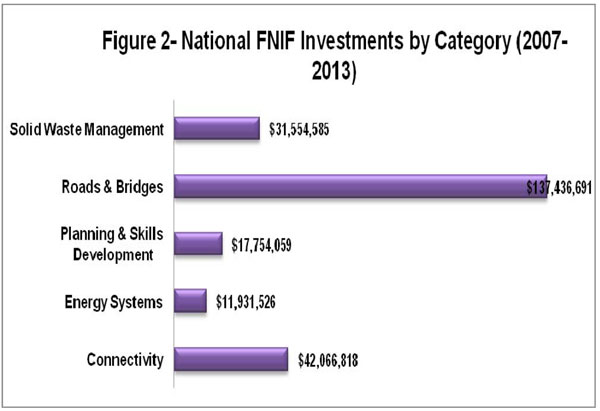

Through the FNIF, $240,743,679 was invested in 434 projects across Canada between 2007 and 2013. Specifically, 253 First Nation communities and 20 additional tribal councils and other organizations received funding under the original four FNIF categories while 274 communities were connected to broadband through funding agreements with 13 tribal councils and organizations as well as seven individual communities. The 434 projects included 150 in planning and skills development, 142 in road and bridges, 81 in solid waste management, 41 in energy systems, and 20 in connectivity.

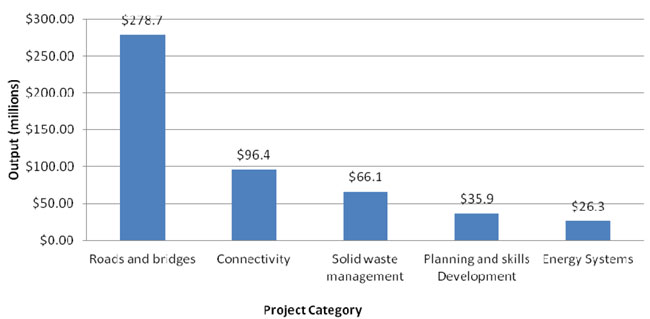

Description of figure 1

This is a bar chart that identifies the proportion of project numbers by the following categories: Connectivity - 20 projects, Energy Systems - 41 projects, Planning and Skills Development - 150 projects, Roads and Bridges - 142 projects and Solid Waste Management - 81 projects.

Description of figure 2

This is a bar chart that identifies investments by categories: Connectivity - $42,066,818, Energy Systems - $11,931,526, Planning and Skills Development - $17,754,059, Roads and Bridges - $137,436,691 and Solid Waste Management - $31,554,585

The regional breakdown for the original four FNIF categories is as followsFootnote 48:

| Province | # of funded First Nation communities per province (excluding connectivity) |

# of organizations/tribal councils that received funding per province |

|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 94 | 4 |

| Ontario | 47 | 5 |

| Manitoba | 30 | 1 |

| Alberta | 29 | 1 |

| Quebec | 21 | 4 |

| Saskatchewan | 21 | 3 |

| New Brunswick | 6 | 2 |

| Nova Scotia | 3 | |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 | |

| Total | 253 | 20 |

The FNIF was able to target a large cross section of communities across the country. Overall, 43 percent of Canada's First Nation communities eligible for funding received funding for FNIF projects under the four original categories. Specifically, 47 percent of British Columbia's 198 communities; 34 percent of Ontario's 139 communities; 48 percent of Manitoba's 63 communities; 60 percent of Alberta's 48 communities; 54 percent of Quebec's 39 communities; 30 percent of Saskatchewan's 70 communities; 40 percent of New Brunswick's 15 communities; 23 percent of Nova Scotia's 13 communities; 50 percent of Prince Edward Island's two communities; and 35 percent of Newfoundland and Labrador's four communities received FNIF funding (excluding connectivity projects).

In terms of the overall economic impact of the FNIF, since 2007, the $235 million invested into Aboriginal communities through the FNIF is estimated to have generated $503 million in total economic output, including $250 million towards Canadian national GDP. The funding has created 2,800 jobs with $162 million in associated revenues.Footnote 49

4.1.1 Impacts of Roads and Bridges Projects

| Total FNIF Funding | $137,436,691 |

|---|---|

| Total Number of Projects | 142 |

| Types of Funded Projects | New construction, reconstruction, upgrade, planning. |

| Number of Funding Recipients | 111 |

| Minimum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $5,700 |

| Maximum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $8,915,000 |

| Median Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $650,000 |

| Total $ Value of Additional Project Funds | $51,284,993 (38%) |

| Partners Involved | Provinces, Saskhighway |

Key Impacts with Examples

1. Improved community accessibility

Lac Seul First Nation's causeway has transformed the ability of the remote community to more easily access basic supplies, health care and employment opportunities in surrounding areas. According to interviewees, new and upgraded roads also improved the accessibility of the First Nation to other communities, thereby increasing tourism and investment opportunities on reserve.

2. Better health and safety outcomes from reduced dust

Fisher River Cree Nation's road paving project has increased safety for pedestrians who are now more clearly visible to drivers and reduction of dust has mitigated health concerns. In communities with dirt roads, respiratory issues were a priority concern.

3. Safer roadways and bridges

Inspections of roads and bridges are conducted through the three year Asset Condition Reporting System. In March 2011, 87.4 percent of the 222 bridges inspected were rated as "new", "good" or "fair" condition (65 percent were good or new) and 82 percent of roads were rated as "new", "good" or "fair" condition (41 percent were good or new). The FNIF contributed to raising these numbers by building new roads and bridges or improving existing assets.

For example, Poplar River First Nation's road repair project has improved the journey into and around the community for school buses, water delivery vehicles and fire trucks. Additionally, multiple communities within the Roads and Bridges case study reported less flipped vehicles when roads were paved. Similarly, sidewalk projects (sometimes accompanied by street lighting in the energy systems category) were popular with interviewees who discussed significant safety improvements.

Namgis First Nation had major road safety concerns after a young girl was killed while walking home at night. As a result of this accident, the community put together a FNIF proposal for a boardwalk along the waterfront that is now frequented by community members and neighbouring communities.

4. Lower vehicle maintenance and road maintenance costs

Community members in Poplar River First Nation and Whitecap Dakota First Nation indicated that fewer repairs are necessary on their vehicles as a result of improved roadways. For Whitecap Dakota First Nation, paved roads are more cost effective to maintain than the previous gravel roads.

Key Challenges

Costs are significant for road and bridge construction and repair with little available funding sources. For one FNIF-funded community, a bridge was purchased from a neighbouring community. However, some repairs are still necessary, for which they do not have available funds. Practically, this means that water trucks can only carry 80 percent of their capacity and heavy machinery cannot be transported across it.

In terms of monitoring road and bridges assets, in many cases, inspection data have not been uploaded to the Integrated Capital Management System either because of challenges with the system discussed above or because assets reviews have not yet been conducted. This means that the Department does not have a clear understanding of the funded road/bridge inventory or road/bridge conditions.Footnote 50

Expected Return on Investment

To determine the return on investment for the construction or repair of road/bridges, projects have often been evaluated using the cost benefit analysis method.Footnote 51 A World Bank econometric study that builds on a body of this research found that for the period 1983-1992, the average economic rate of return for road building projects was 29 percent.Footnote 52 According to David Canning and Esra Bennathan, an economic rate of return such as this "might be described as adequate but not exceptional."Footnote 53 However, the literature notes that justification for infrastructure projects through their economic contribution is "extremely controversial, and consists of studies that are divided on both the magnitude and direction of the net effect of infrastructure spending on economic growth."Footnote 54 Additionally, Chandra and Thompson note that the economic impact of infrastructure investments in non metropolitan areas remains unclear as 'leakages' are present for certain types of infrastructure projects. For example, new or improved roads/bridges may lead economic activity to shift to nearby metropolitan areas due to the reduced travel time.Footnote 55

Furthermore, Canning and Bennathan state that microeconomic analysis has the potential to overlook externalities, in particular positive externalities, of infrastructure investment. For example, road projects can increase competition and access to markets as well as facilitate access to health, education and other important services.Footnote 56 The authors attempt to include the impact of externalities in their study in order to determine the 'social return on investment' for road projects. While Canada is not included in the study by Canning and Bennathan, the rates of social return on road projects from comparable countries, such as Australia (-1 percent) and the United States (seven percent), are.Footnote 57 While these rates of social return on investment are low, the authors note that the rates of social return were highest in countries with infrastructure shortages.Footnote 58 Therefore, as infrastructure in First Nation communities is commonly lacking relative to other communities in Canada, the social rate of return is likely to be higher than experienced elsewhere in the country.

However, studies promoting the social impact of infrastructure projects have also come under criticism for the quality of their evidence. For instance, Dominique Van de Walle notes that social benefits claimed for infrastructure projects, and in particular the impact of rural road construction, have little convincing empirical evidence.Footnote 59 In Van de Walle's view "although the argument that high social benefits will ensue is sometimes plausible, the evidence provided in justification is rarely so" and furthermore "without better evidence, there can be no presumption that such benefits will be high or even positive."Footnote 60 The author notes that there are so many contributing factors to the benefits claimed by rural road advocates, such as increased educational achievement, that it is hard to attribute these successes to a road project.Footnote 61 As a result, the true return on investment for road and bridge projects is difficult to determine. However, the economic impact analysis for the FNIF estimates that the Roads and Bridges category investment, excluding leveraged funds, generated $278.7 million in output. This included $129.4 million toward Canadian GDP, $83.3 million in income and 1,396 jobs in total.Footnote 62

4.1.2 Impacts of Solid Waste Management Projects

| Total FNIF Funding | $31,554,585 |

|---|---|

| Total Number of Projects | 81 |

| Types of Funded Projects | Construction of transfer stations and landfills, equipment |

| Number of Funding Recipients | 70 |

| Minimum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $10,000 |

| Maximum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $3,483,800 |

| Median Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $138,897 |

| Total $ Value of Additional Project Funds | $5,353,354 (20%) |

| Partners Involved | None |

Key Impacts

1. Reduced burning of garbage and less contamination of groundwater (environmental and health benefits)

For Kitasoo First Nation, leachate from the previous landfill was discharging into the ocean. Through the construction of a transfer station and an agreement with the Naut'sa mawt Tribal Council, Robanco and North Arm Barging, the community moves their "sorted" solid waste off reserve.

2. Future cost savings

In both Quebec and British Columbia, where First Nations sometimes dispose of waste off reserve and are thus subject to provincial regulations, provincial governments, will soon charge fines for communities that do not comply with new regulations, including composting regulations in British Columbia and recycling and other waste management activities in Quebec.

FNIF funding has been used in both cases to help First Nation communities transition to compliance with provincial regulations, which will result in future cost savings. In 2010, the Quebec Government updated its Residual Material Management Policy, imposing an additional fee of $9.50 for each tonne of residual waste disposed of in the provinceFootnote 63; savings here will be significant.

3. Communities are reducing, reusing and recycling

Multiple case study interviewees discussed additional waste management projects that they are now pursing in conjunction with their FNIF funded projects. In Heiltsuk First Nation, items being sent to the new transfer station are first identified for salvage and donation to interested community members before being disposed as a last resort. The community has also begun a composting project.

Key Challenges

A noted key challenge for all regions engaged in the funding of waste transfer stations was the need for last minute training for operators. AANDC regional office staff in some cases needed to quickly develop training sessions to provide First Nation Public Works staff with the necessary skills to run the transfer stations.

Similarly, the need for complementary community education campaigns was widespread as community members were often dumping toxic and other non-desirable materials, resulting in surcharges to the band administration when removing the waste. In some cases, fencing and security guards were necessary as surrounding populations were found to be trespassing and improperly dumping materials. Communities such as Peguis First Nation and Whitecap Dakota First Nation addressed these challenges by building a fence, hiring and training operators, publishing instructions in the community newsletter and delivering a community outreach campaign.

Expected Return on Investment

As cost savings under various solid waste management regimes vary from place to place, the literature emphasizes return on investment in terms of reduction of greenhouse gases. Levis et. al. use a computer-generated model to determine the estimated reduction based on given levels of investment. They find that a $48 million investment in a combination of recycling, waste-to-energy stations (where combustibles are sent and turned into fuel) and landfills will yield a roughly 1.8 billion metric tonne reduction of carbon dioxide emissions over 20 years, the equivalent of taking almost 370 million cars off the road.Footnote 64 Furthermore, a $64 million investment yields a 14 billion tonne reduction (or almost three billion cars) in the same time. Thus, the return on investment in solid waste management in terms of community and environmental health is significant. This is especially significant considering that in 2007, Environment Canada recognized landfills, solid and hazardous wastes, as well as the air emissions from incineration and open burning of garbage as significant on-reserve risks requiring immediate attention.Footnote 65

The economic impact analysis for the FNIF estimates that the Solid Waste Management category investment, excluding leveraged funds, generated $66.1 million in output. This included $40.2 million toward Canadian GDP, $27.3 million in income and 552 jobs in total. Footnote 66

4.1.3 Impacts of Energy Systems Projects

| Total FNIF Funding | $11,931,526 |

|---|---|

| Types of Funded Projects | 41 |

| Types of Funded Projects | Energy retrofits, street lights, green energy upgrades such as solar power, hydroelectric development |

| Number of Funding Recipients | 37 |

| Minimum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $7,800 |

| Maximum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $2,050,000 |

| Median Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $136,800 |

| Total $ Value of Additional Project Funds | $29,256,122 (245%) |

| Partners Involved | Private sector energy compan ies to construct projects and provide training. Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (now Employment and Social Development Canada) funding training for community members to acquire energy certification. |

Key Impacts

1. Improved energy security

In Kitasoo First Nation, a lack of energy capacity caused frequent brown-outs that affected community members and the key economic center, a fish plant. Furthermore, Kitasoo First Nation stopped building vital housing because there simply was not enough electricity to support development. In this context, the new hydro electric generator will significantly improve energy security and allow Kitasoo First Nation to continue with housing expansion and business activities.

2. Reduced diesel dependence (cost savings and environmental benefits)

Following research funded by the ecoENERGY programFootnote 67, the community of Wawakapewin First Nation in northern Ontario received FNIF funds to install a 50 kw summer generator and 25 kw solar panels. These will be used to reduce the community's reliance on diesel, and it is estimated that this will cut consumption of fuel by 14,000 L per year. This will yield an estimated reduction of 10.5 metric tonnes in green house gases and $17,000 in fuel costs. Given that fuel prices fluctuate, one key informant mentioned the savings could be as high as $42,000 otherwise spent on diesel, which tends to cost $1.30 more per barrel in Wawakapewin First Nation than elsewhere due to increased fuel costs in remote locations.

3. Increased use of alternative energy sources (economic and environmental benefits)

T'Souke First Nation undertook a $1.25 million solar energy project, which has succeeded in making the community a "net zero" consumer; they are able to produce and sell energy in the summer to British Columbia hydro, which they use to cover their minimal energy bills in the winter, equaling zero costs at year end.

Expected Return on Investment:

Chris Henderson is a co-founder of the Delphi Group and Lumos Enery who has worked in the clean energy field with First Nation communities for over 25 years. According to Henderson, supporting First Nation communities in the development of renewable energy resources is a proven path toward energy security and Aboriginal prosperity. As of November 2013, Henderson has noted that across Canada there are 27 alternative energy projects in operation that are partially owned by a First Nation with 11 soon to be commissioned, 13 in construction, 30 in the feasibility stage, and 46 being analyzed. In total, this represents 127 projects poised to provide increased energy security and a source of own-source revenue for communities.Footnote 68

The FNIF facilitated investments to improve energy security as a matter of health and safety for communities. As a secondary benefit, many experts and academics in the field argue that energy security is a foundational requirement for improving the economic prosperity of communities by allowing businesses to develop and thrive. Additionally, as Henderson argues, the energy industry itself is an opportunity for First Nations to prosper. According to Henderson's research, communities - such as T'Souke First Nation- are using clean-energy projects to create new jobs and fuel long-term investment in economic prosperity. He states that "for First Nation, Métis and Inuit peoples, clean-energy projects must become an economic engine, not just for today, but also for well into the future."Footnote 69 To do this, he argues, it cannot be just about locating temporary employment opportunities or negotiating impact benefit agreements; instead, in order to "to succeed in the business of clean energy, Aboriginal communities need to shift to being active partners in business relationships that are founded on enterprise and effort."Footnote 70

Core ingredients for developing a prosperous clean-energy industry for First Nations include solid community planning, capacity building and human resources training for green jobs. Henderson demonstrates this point by drawing on a number of community examples with the Ojibway of the Pic River First Nation as a noteworthy success. Although not a FNIF funded project, the Pic River example provides insight to the possibilities of an expected return on investment for First Nation energy projects. The Pic River First Nation has taken equity positions in several hydropower projects since 1983 and in return, the band has received employment, income and social stability. The key statistics are as follows:Footnote 71

- A 23 MW hydro-generating plant was constructed

- Its electricity generated can power 17,000 residential homes

- The plant will be the community's financial foundation for 50+ years

- Revenue provided $20 million in income for the local economy during construction

- It has lifecycle income of $400 million (hydroelectric assets have climbed to about $1 million per year helping to finance a women's crisis centre, a youth centre, a recreation center, cable television and high-speed internet services)

- Fifty jobs were created during construction

- Two full-time operating positions were created

Henderson compares this outcome to impact benefit agreements such as where $15,000 was paid to every man, woman and child in the Inuit community of Saluit, Quebec in 2008 by Xstrata. Given this agreement provided for a direct cash payment, "the money disappeared fast and failed to improve the community's economic prospects."Footnote 72

Henderson's findings are corroborated by Brenneman and Kerf's World Bank comprehensive literature review of the impacts of investment in infrastructure, which notes that the many benefits of energy systems include lowering the cost of energy, enhancing the productivity of small businesses and fostering local employment.Footnote 73

The economic impact analysis for the FNIF estimates that the Energy Systems category investment, excluding leveraged funds, generated $26.3 million in output. This included $12.6 million toward Canadian GDP, $8 million in income and 132 jobs in total.Footnote 74

4.1.4 Impacts of Community Planning and Skills Development Projects

| Total FNIF Funding | $17,754,059 |

|---|---|

| Total Number of Projects | 150 |

| Types of Funded Projects | Comprehensive Community Plans, Training, Geographical Information System |

| Number of Funding Recipients | 120 |

| Minimum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $4,744 |

| Maximum Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $1,000,000 |

| Median Amount Invested by AANDC for a Project | $92,000 |

| Total $ of Additional Project Funds | $5,073,101 (29%) |

| Partners Involved | In terms of supporting CCPs, regional funders were only noted in British Columbia, including New Relationship Trust, Union of British Columbia Municipalities, First Nations Summit, Aboriginal Business Canada, Western Economic Diversification, Natural Resources Canada, Environment Canada, Real Estate Foundation of British Columbia, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Public Safety Canada, Health Canada, BC Hydro, RBC Industry Canada |

Key Impacts

1. Long-term sustainable community development

Of the 150 Planning and Skills Development projects funded by the FNIF, approximately 117 were for community planning components with the highest number of projects funded in the British Columbia region. The remaining 33 funded projects were directed toward infrastructure training initiatives.

The production of comprehensive community plans in particular provided communities with a foundational document that articulated a common community vision and key priorities. Moving forward, high engagement and buy-in of involved community members allows for long-term sustainable community development. Overall, the impacts of CCPs were varying but when successful, were significant. For Westbank First Nation, the planning processes culminated in a Community Planning Law. As a result, council cannot act in contradiction to the Plan. Additionally, the Council is obligated to continually engage the community when implementing their plans. The Plan has also become the foundation for developing other community laws.

For one chief interviewed, the CCP was about giving the community a collective vision; he stated, "The community was always asking, 'who are we?' So I wanted to show them who they are." For him, the CCP was essential to bringing people together to collectively design a future. It was about showing them who they are through positive messaging billboards around the community; in reviving traditional ceremonies; on electronic photo screens in the new school showing their community at play; on street signs written in their traditional language; and in the bricks and mortar of their buildings.

Multiple case study interviewees noted that the process of developing a CCP led to community healing and increased cohesion. While difficult to quantify, this impact certainly enhances community sustainability in the long run.

2. Improved First Nations' infrastructure management and technical capacity to maintain infrastructure

The Planning and Skills Development category allowed funding recipients to engage in training to enhance their technical capacity to maintain infrastructure or to engage in infrastructure planning activities. In terms of training, projects such as the "Oil Fired Forced Air Furnaces and Safe Transportation of Diesel Fuel Workshops" for the Keewatin Tribal Council allowed communities to upgrade their skills and expertise. However, the vast majority of funding in this category was provided for planning. Funded planning activities and final documents took on a variety of forms. Key informants noted some plans were completed by experts and were thus highly technical in nature and provided a plan for future economic development and how infrastructure should be developed, used and connected for maximum benefits. Although these types of plans were very relevant to infrastructure management, they often proved less useful to community members who did not feel engaged in the process and thus supportive of the final plan.