Archived - Summative Evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education Program on Reserve

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: June 2012

PDF Version (844 Kb, 95 Pages)

Table of contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response /Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Efficiency and Economy

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Survey Guides

- Appendix B - Key Informant Interview Guides

- Appendix C - Case Study Tools

- Appendix D - ESE Components by Authority

List of Acronyms

- AFA

- Alternative Funding Arrangement

- BC

- Block Contribution

- B.C.

- British Columbia

- CEC

- Cultural Education Centres

- CFA

- Comprehensive Funding Arrangement

- CFNFA

- Canada/First Nations Funding Arrangement

- CWBI

- Community Well-Being Index

- ECE

- Early Childhood Education

- ECCD

- Early Childhood Care and Development

- EPMRB

- Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

- EPMRC

- Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

- ESE

- Elementary/Secondary Education

- FC

- Fixed Contribution

- FNEC

- First Nations Education Council

- FNESC

- First Nations Education Steering Committee

- FNRMO

- First Nation Regional Education/Management Organizations

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- FTP

- Flexible Transfer Payment

- HCSE

- High-Cost Special Education

- HQ

- Headquarters

- K-12

- Kindergarten to grade 12

- OAG

- Office of the Auditor General

- PSE

- Post-Secondary Education

- QAS

- Quality Assurance Strategy

- SC

- Set Contribution

- SEP

- Special Education Program

Executive Summary

This summative evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education (ESE) Program was conducted in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13. It follows a formative evaluation of the ESE Program in 2010, which provided a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC).

This evaluation was conducted concurrently with the summative Evaluation of Post-Secondary Education programming in order to obtain a holistic understanding of AANDC's suite of education programming and its impact on First Nation and Inuit communities.

The primary objective of elementary/secondary education programming is to provide eligible students living on reserve with education programs comparable to those that are required in provincial schools by the statutes, regulations or policies of the province in which the reserve is located.

AANDC's elementary/secondary education programming is primarily funded through seven authorities: Grants to participating First Nations and First Nations Education Authority pursuant to the First Nations Jurisdiction over Education in British Columbia Act; Grants to Indian and Inuit to provide elementary and secondary educational support services; Grants to Inuit to support their cultural advancement; Payments to support Indian, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education (including Cultural Education Centres; Indians Living On Reserve and Inuit; Registered Indian and Inuit Students; Special Education Program; and Youth Employment Strategy); Grants for Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia; Contributions under the First Nations SchoolNet services to Indians living on reserve and Inuit; and Contributions to First Nation and Inuit Governments and Organizations for Initiatives under the Youth Employment Strategy Skills Link program and Summer Work Experience Program.

The evaluation examined the following components of ESE programming: instructional services for Band Operated Schools, Federal Schools and Provincial Schools; Elementary and Secondary Student Support Services; New Paths for Education; Teacher Recruitment and Retention; Parental and Community Engagement; First Nation Student Success Program; Cultural Education Centres; Special Education; Education Partnerships Program; and First Nations SchoolNet.

In line with Treasury Board Secretariat requirements, the evaluation looked at issues of relevance (continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities), performance (effectiveness) as well as efficiency and economy.

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of seven lines of evidence: case studies, expenditures analysis, student data analysis, document and file review, key informant interviews, literature review and surveys (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix).

Four contractors were contracted to handle specific lines of evidence for which they have expertise. Donna Cona Inc. undertook key informant interviews and case studies; Harris/Decima conducted surveys; KPMG provided the expenditures analysis; and the University of Ottawa carried out a meta-analysis of available literature. The evaluation team worked closely with them to determine the most appropriate and rigorous approaches to the methodologies, and conducted most of the final analysis in-house. Additionally, a secondary literature review was completed to assess broader issues of governance and the coverage of education programs.

Stemming from this review, this evaluation found the following:

Relevance

- There is a need for continued investment in the Authorities for Elementary/Secondary Education stemming from projected population growth and from the need for significant improvement in student outcomes.

- Education authority activities are generally aligned with Government of Canada priorities; however, recent major reforms are reflective of the need to better align activities and better ensure improvements in student success.

- The priorities as stated by First Nation Education Authorities and those of AANDC are aligned insofar as the need to address marked gaps in educational opportunities and success. However, First Nation participants emphasise key priorities in the areas of cultural and language retention as being critical to success, and emphasise the need to recognise key differences in learning needs and the current state of education gaps, rather than simple notions of comparability.

- The role of the Government of Canada in ESE programming is generally appropriate; however, policy changes with respect to service delivery and local operational control may have implications on this role in the future.

Performance - The intended outcome of education opportunities and results that are comparable to the Canadian population is not being achieved.

- Continued work is needed to better facilitate constructive engagement and collaborative networks between First Nation education authorities, and where appropriate, with provincial governments or other organisations, and there is evidence that AANDC programming is improving in this regard.

- Student success is associated with parental engagement, the level of education in the community and the strength of the local economy. There are deeper issues related to the historical trauma of residential schools that may be interrelated with these factors.

- Community governance, the quality of teacher instruction and the quality of school curriculum were suggested as key factors affecting student success.

- Expenditures to First Nations and tribal councils for the operation of schools do not appear to account for actual cost variability applicable to the needs and circumstances of each community or school, and particularly the cost realities associated with isolation and small population. There is a need for a more strategic understanding of resource needs and allocation methods.

- Jurisdictional issues, implications for the provision of second- and higher-level services, and early childhood and adult education are considerations of significant importance in future policy development.

- Many First Nation schools and communities are not adequately resourced to provide proper assessments and services to meet the needs of First Nation students with special needs.

Efficiency and Economy - The current approach to programming may not be the most efficient and economic means of achieving the intended objectives of ESE programming.

Based upon these findings, it is recommended that AANDC:

- Develop a strategic and transparent framework for the investment of new funds that are explicitly allocated to facilitate improvements in student success in the short-term;

- Undertake further research into funding allocation methodologies that are equitable to provincial approaches, while at the same time accounting for cost realities on reserve;

- Ensure that future policy and program exercises develop clearly defined roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for Elementary and Secondary Education;

- Explore and pursue options for the comprehensive development of second and higher-level services where possible and appropriate to reduce administrative burden and overhead costs, while supporting First Nations in developing long-term capacity for service management;

- Work with First Nations to develop strategies to strengthen culture and language retention as it relates to better student outcomes;

- Examine the implications of integrating support for early childhood education in AANDC's education portfolio;

- Examine the implications of integrating support for adult education in AANDC's education portfolio; and

- Develop a strategy to work with First Nations in building the capacity to strengthen the provision of special needs assessments and services.

Management Response /Action Plan

Project Title: Summative Evaluation of Elementary and Secondary Education

Project #: 1570-7/09057

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Develop a strategic and transparent framework for the investment of new funds that are explicitly allocated to facilitate improvements in student success in the short term. | Agree in Principle, with respect to Recommendations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8. | Stephen Gagnon, Director General, Education Branch ESDPP |

Start Date: Completion: |

| In Budget 2008, the Government of Canada announced the First Nation Student Success Program (FNSSP). The FNSSP supports projects aimed at improving student outcomes in reading, writing and mathematics as well as those aimed at school retention. The department's web site describes: the program objectives in detail; the assessment and selection process; as well as Program Guidelines. Pursuant to commitments outlined in Budget 2012, the Government of Canada will:

The findings of this evaluation will be taken into account when developing options for moving forward. |

|||

| 2. Undertake further research into funding allocation methodologies that are equitable to provincial approaches, while at the same time accounting for cost realities on-reserve. | |||

| 3. Ensure that future policy and program exercises develop clearly defined roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for Elementary and Secondary Education. | |||

| 4. Explore and pursue options for the comprehensive development of second and higher-level services where possible and appropriate to reduce administrative burden and overhead costs, while supporting First Nations in developing long-term capacity for service management. | |||

| 5. Work with First Nations to develop strategies to strengthen culture and language retention as it relates to better student outcomes. | |||

| 8. Develop a strategy to work with First Nations in building the capacity to strengthen the provision of special needs assessments and services. | |||

| 6. Examine the implications of integrating support for early childhood education in AANDC's education portfolio. | Concur in part Early childhood education and adult education are under the mandate of Health Canada and HRSDC, respectively. To the extent that integrating early childhood education and adult education fall within the mandates of other departments, the recommendation raises machinery of government issues that are beyond this Department's abilities/authority to change. To the extent possible, the department will work to develop early literacy programming, high school retention and active measures to ensure that the coverage of the various department's responsibilities is coordinated. |

Stephen Gagnon, Director General, Education Branch ESDPP |

|

| 7. Examine the implications of integrating support for adult education in AANDC's education portfolio. |

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by:

Françoise Ducros

Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector (ESDPP)

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This summative evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education (ESE) Program was conducted in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13. It follows a formative evaluation of the ESE Program in 2010, which provided a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and was required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program as of March 31, 2010.

This evaluation was conducted concurrently with the summative Evaluation of Post-Secondary Education (PSE) programming in order to obtain a holistic understanding of AANDC's suite of education programming and its impact on First Nation and Inuit communities. This approach allowed the evaluation team to minimise costs and reduce the burden for individuals and communities by collecting all the information at one time.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the Parliament of Canada legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians." Canada exercised this authority by enacting the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, the enabling legislation for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary school services to Indian children living on reserves, providing the Department with a legislative mandate to support elementary and secondary education for registered Indians living on reserve.

Since the early 1960s, AANDC has sought incremental policy authorities to undertake a range of activities to support the improvement in the socio‑economic conditions and overall quality of life of registered Indians living on reserve. These activities include support for cultural education for Indians and Inuit. Thus, AANDC considers its involvement in cultural education programs as a matter of policy.

Although there have been significant gains since the early 1970s, First Nation participation and success in elementary and secondary education still lags behind that of other Canadians. Drop‑out rates are higher for First Nations than other Canadian students. Increasing Indian and Inuit retention rates and successes at the elementary/secondary programming level will support the strategic goal of greater self-sufficiency, improved life chances, and increased labour force participation.

AANDC's elementary and secondary programming is primarily funded through the following authorities:Footnote 1

- Grants to participating First Nations and First Nations Education Authority pursuant to the First Nations Jurisdiction over Education in British Columbia Act;

- Grants to Indian and Inuit to provide elementary and secondary educational support services;

- Grants to Inuit to support their cultural advancement;

- Payments to support Indian, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education (including Cultural Education Centres; Indians Living On Reserve and Inuit; Registered Indian and Inuit Students; Special Education Program; and Youth Employment Strategy);

- Grants for Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia;

- Contributions under the First Nations SchoolNetFootnote 2 services to Indians living on reserve and Inuit; and

- Contributions to First Nation and Inuit Governments and Organizations for Initiatives under the Youth Employment Strategy (YES) Skills Link program and Summer Work Experience Program.Footnote 3

In addition to core program funds for ESE, the evaluation looked at several complimentary programs, which aim to improve the quality of education in First Nation schools and student outcomes. They include:

- the Special Education Program (SEP), which supports students with moderate to profound special education needs;

- New Paths for Education, Teacher Recruitment and Retention, and Parental and Community Engagement – which provide proposal based funding for initiatives designed to strengthen First Nations education management, improve the effectiveness of classroom instruction, and support community and parental involvement in the education of children and youth;

- the Education Partnerships Program, which supports proposals for tripartite education partnership arrangements between the Government of Canada, First Nations and provinces in order to help advance First Nations student achievement in First Nations and provincial schools;

- the First Nations SchoolNetFootnote 4 Program, which focuses on improving the connectivity and technical capacity of kindergarten to grade 12 (K-12) schools on reserve;

- the Cultural Education Centres (CEC) Program, which currently funds 110 Cultural Education Centres; and

- the First Nation Student Success Program, which provides support to proposals that are aimed at improving student and school outcomes through investments in school success plans, student learning assessments, and performance measurement.

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The overall objective of ESE programming is to provide eligible students living on reserve with education programs comparable to those that are required in provincial schools by the statutes, regulations or policies of the province in which the reserve is located. The objective is that eligible students will receive a comparable education to other Canadians within the same province of residence and achieve similar educational outcomes to other Canadians, and with attendant socio-economic benefits to themselves, their communities and Canada.

In AANDC's Program Activity Architecture, education falls under the strategic outcome "The People," whose ultimate outcome is "individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit." Education is its own program activity, which includes the following sub‑activities covered in this evaluation: Elementary and Secondary Education, First Nations and Inuit Youth Employment Strategy, Education Agreements, Special Education and Cultural Education Centres.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The management of education programming at AANDC is undertaken by the Education Branch in the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector (ESDPP).

In order to be eligible for elementary/secondary education, a student must:

- be attending and enrolled in a federal, provincial, band‑operated or private/independent school recognized by the province in which the school is located as an elementary/secondary institution;

- be aged 4 to 21 years (or the age range eligible for elementary and secondary education support in the province of residence) on December 31 of the school year in which funding support is required, or a student outside of this age range who is currently funded by AANDC for elementary and secondary education;

- be ordinarily resident on reserve; and

- have demonstrated need for education student support and that the Chief and Council have asked AANDC to deliver these services, thus, no other source of funding can meet such a need.

Grants are administered directly by AANDC on behalf of First Nations. Grants are provided when Chiefs and Councils choose to continue having AANDC deliver support services on reserve or some components of program funding. AANDC may make a grant payment directly to individual First Nation or Inuit recipients.

Funding for the ESE and SEP programs may be flowed directly to chiefs and councillors, or to organizations designated by chiefs and councillors (bands/settlements, tribal councils, education organizations, political/treaty organizations, public or private organizations engaged by or on behalf of Indian bands to provide education services, provincial ministries of education, provincial school boards/districts or private education institutions).

In addition, AANDC may also enter into agreements with provincial education authorities for the delivery of elementary/secondary education services; with private firms to administer program funds jointly with or on behalf of the First Nation (i.e., co-managers, or third-party managers); with education authorities or First Nation Regional Education/Management Organizations (FNRMO) or in some cases, AANDC may deliver services directly on behalf of First Nations (e.g., in the remaining seven federal schools).

Contributions for the SEP may also be flowed directly to FNRMO's who deliver direct and indirect services. The following six FNRMOs deliver direct and/or indirect services for SEP:

- First Nations Education Steering Committee (FNESC) in British Columbia

- First Nations Education Council (FNEC) and l'Institut Culturel et Éducatif des Montagnais in Quebec

- Prince Albert Grant Council and Battlefords Tribal Council in Saskatchewan

- Manitoba First Nations Resource Centre

- Mi'Kmaq Education in Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick Education Initiative

Funding for First Nations SchoolNet is flowed directly to the FNRMOs, which deliver direct and indirect services. They include the following organizations:

- FNESC servicing British Columbia

- Keewatin Career Development Corporation servicing Alberta and Saskatchewan

- Keewatin Tribal Council servicing Manitoba

- Keewaytinook Okimakanak/Northern Chiefs Council Network servicing Ontario

- FNEC – Technology, servicing Quebec

- Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey servicing the Atlantic provinces

Additionally, AANDC funds the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. For Cultural Education Centres, AANDC directly funds First Nations, Inuit and Innu cultural education centres. AANDC also funds the First Nations Confederacy of Cultural Education Centres who manages the funds and administration for a majority of First Nations Cultural Education Centres.

Eligible recipients for block contributions are First Nations and tribal councils.

1.2.4 Program Resources

In 2010-11, AANDC spent nearly $1.8 billion on education,Footnote 5 approximately $1.5 billion of which was spent on ESE programming. Table 1, below, provides a breakdown of total ESE funding from 2006-07 to 2010-11.

| Region | 06/07 | 07/08 | 08/09 | 09/10 | 10/11 | Total ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | $35,371,340 | $39,930,003 | $41,618,262 | $47,727,998 | $47,596,941 | $212,244,544 |

| Quebec | $87,482,268 | $89,929,515 | $92,310,524 | $97,098,323 | $101,184,025 | $468,004,655 |

| Ontario | $234,021,762 | $237,866,555 | $243,442,766 | $251,463,050 | $261,988,043 | $1,228,782,176 |

| Manitoba | $215,828,958 | $226,466,397 | $232,172,382 | $239,441,473 | $242,482,991 | $1,156,392,201 |

| Saskatchewan | $174,891,081 | $179,603,443 | $185,579,852 | $200,162,367 | $211,673,006 | $951,909,749 |

| Alberta | $184,400,660 | $190,523,973 | $196,374,326 | $203,657,405 | $208,047,581 | $983,003,945 |

| British Columbia | $169,536,542 | $172,976,689 | $175,774,570 | $181,449,148 | $183,183,848 | $882,920,797 |

| Yukon | $1,277,722 | $1,199,009 | $1,190,529 | $1,626,894 | $1,513,789 | $6,807,943 |

| NWT | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Nunavut | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| HQ Admin | $12,242,757 | $8,714,850 | $10,333,780 | $19,932,787 | $15,563,273 | $66,787,447 |

| SUB-TOTAL Footnote 6 | $1,115,053,090 | $1,147,210,434 | $1,178,796,991 | $1,242,559,445 | $1,273,233,497 | $5,956,853,457 |

| Band Support Funding and Band Employee Benefits Footnote 7 |

$86,598,945 | $88,533,520 | $92,288,302 | $92,973,141 | $96,592,818 | $456,986,726 |

| SUB-TOTAL: K-12 EDUCATION | $1,201,652,035 | $1,235,743,954 | $1,271,085,293 | $1,335,532,586 | $1,369,826,315 | $6,413,840,183 |

| Education Agreements Footnote 8 | $127,969,860 | $137,402,303 | $143,170,317 | $146,705,800 | $156,842,473 | $712,090,753 |

| TOTAL: K-12 EDUCATION EXPENDITURES | $1,329,621,895 | $1,373,146,257 | $1,414,255,610 | $1,482,238,386 | $1,526,668,788 | $7,125,930,936 |

ESE programming is funded through annual Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFA) and five-year Canada/First Nations Funding Agreements (CFNFA). These arrangements include various funding authorities, such as grants, set contributions (SC), fixed contributions (FC), and block contributions (BC).Footnote 9 Appendix C outlines ESE program components by funding authority.

All components of the ESE Program are eligible for funding under set contributions, fixed contributions and block contributions with the exception of the following program components: funding to Federal Schools, funding for New Paths, funding for Enhanced Teacher Salaries, the accountability initiatives including performance measurement systems, student assessments, school success plans and initiatives to encourage collaboration between Aboriginal organizations, federal, and provincial governments. The excepted items are eligible only for contribution funding.

Effective April 1, 2011, AANDC began using additional fixed, flexible and block contribution funding approaches for transfer payments to Aboriginal recipients, as described in the Directive on Transfer PaymentsFootnote 10 and according to departmental guidelines for the management of transfer payments. Prior funding for PSE through Alternative Funding Arrangement (AFA) or Flexible Transfer Payment (FTP) mechanisms will remain in effect, as required, until the expiration of existing funding arrangements that contain these mechanisms. Following this, AFA will become Block Contributions and FTP will become Fixed Contributions.

The allocation of program funding involves the distribution of funds from Headquarters (HQ) to the regions and from the regions to the recipients. The Department-First Nation Funding Agreements (DFNFAs) are formula-driven, and are consistent throughout the country. The CFA allocation model for the program, on the other hand, varies sometimes significantly by region.

In terms of the allocation of funds from HQ to the regions, program funding is a component of each region's annual core budget. The Education Branch does not determine the amount of program funding to be allocated to each region. This is the responsibility of the Resource Management Directorate in Finance at HQ. National budget increases (currently two percent annually) are allocated to each region in proportion to their existing budgets.

The regions have the authority to allocate funds across the various programs included in their core budget and therefore, ultimately decide the extent of program funding to provide to their recipient.

1.3 Current Evaluations

The current evaluations of ESE and PSE looked at the entire suite of education programming offered by AANDC. In the past, AANDC has evaluated components of its education programming, such as the Evaluation of the First Nations SchoolNet Program (2009), the Evaluation of the Special Education Program (2007), the Summative Evaluation of the Cultural Education Centres Program (2005), and the Summative Evaluation of Band-Operated and Federal Schools (2005). While evaluating programs from this lens has its benefits, the result is a lack of understanding of how all programs affect overall student outcomes. It is expected that evaluating Aboriginal education in this light will provide the Department with a clearer sense of the current state of Aboriginal education and insight on future direction.

Internally, the Branch's evaluation work is informed by its Engagement Policy that provides Branch staff with a framework for including Aboriginal people and organizations in the evaluation process. The underlying principle is that, for evaluations to be relevant to, and have meaning for, Aboriginal people, Aboriginal people need to be fully involved in the evaluation process. As part of this evaluation, Aboriginal involvement was attained through interviews, surveys and case studies (including focus groups).

Furthermore, an Advisory Committee was established, composed primarily of national First Nation and Inuit education organisations, and with representation from AANDC. The purpose of the Advisory Committee was to provide guidance and insights on the development of evaluation tools, and on broader interpretation of findings and forming recommendations. The Advisory Committee representatives met at various stages of the evaluation process to discuss and provide advice on:

- Terms of Reference

- Methodology Reports

- Acquisition of Qualified Consultants

- Potential Key Informants, Case Study Communities and Literature

- Technical Reports

- Evaluation Findings

- Draft Final Evaluation Report

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined the following components of ESE programming: instructional services for Band Operated Schools, Federal Schools and Provincial Schools; Elementary and Secondary Student Support Services; New Paths for Education; Teacher Recruitment and Retention, Parental and Community Engagement, First Nation Student Success Program, Cultural Education Centres, Special Education, Education Partnerships Program and First Nations SchoolNet.

The Terms of Reference were approved by AANDC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) on May 14, 2010. This evaluation provides information on program relevance, performance, and efficiency and economy to support the management of program authorities in compliance with the Policy on Transfer Payments

Four contractors, Donna Cona Inc., Harris/Decima, KPMG and the University of Ottawa were contracted to undertake primary data collection (see Section 2.3). Data collection and analysis was undertaken primarily between September 2010 and April 2012.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the revised evaluation questions approved at EPMRC in September 2010, the evaluation focused on the following issues:

- Relevance

- Is there an ongoing need for the program?

- Is the program consistent with government priorities and AANDC strategic objectives?

- Is there a legitimate, appropriate and necessary role for the federal government in the program?

- Performance

- To what extent have intended outcomes been achieved as a result of the program?

- To what extent has the program influenced the constructive engagement and collaborative networks to further education and skills development?

- What are the factors (both internal and external) that have facilitated and hindered the achievement of outcomes? Have there been unintended (positive or negative) outcomes? Were actions taken as a result of these?

- To what extent has the design and delivery of the program facilitated the achievement of outcomes and its overall effectiveness?

- Efficiency and Economy

- Is the current approach to programming the most economic and efficient means of achieving the intended objectives?

- How could the program be improved?

2.3 Evaluation Methodology

The following section describes the data collection methods used to perform the evaluation work, as well as the major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report and quality assurance.

2.3.1 Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of seven lines of evidence: case studies, data analysis, expenditures analysis, document and file review, key informant interviews, literature review, and surveys (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix). All lines of evidence were collected for this evaluation and the Summative Evaluation of PSE simultaneously to minimise costs and reduce the burden for individuals and communities by collecting all the information at one time.

- Case Studies:

A total of 14 case studies were conducted by Donna Cona Inc. for both Elementary/Secondary and Post-Secondary Education evaluations. Case studies provided qualitative insights into whether intended impacts of education programs, policies and initiatives are occurring, and to allow for a thorough analysis of First Nation perspectives on needs, challenges and best practices in providing a quality education to First Nation and Inuit students.

Seven case studies were conducted using a regionally-based approach, where one community was selected randomly for each AANDC region (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic) while attempting to acquire a general representation of varying community sizes, local economies, and isolation. In these case studies, Donna Cona Inc. was asked to take a holistic approach to education in the community to gain a comprehensive understanding of issues facing individuals and communities more broadly. Case study tools were designed by Aboriginal researchers and customised to include various methods of communication if the respondent so chose.

The regionally focused case studies included, but were not limited to, participation from:- Chiefs and/or member(s) of band councils responsible for education profiles;

- Education office/department managers and staff and/or persons responsible for elementary / secondary / post-secondary school management;

- School principals;

- School counsellors, on-reserve elementary and secondary teachers, cultural centre's staff, elders, staff directly involved in the delivery of on-reserve special education programming;

- Parents of students who attend the school(s);

- Students, aged 16 and over who are involved at school;

- Group sessions may have included Elders, parents and student representatives;

- Off-reserve principals and/or school board administrators; and

- Off-reserve secondary school coordinators, off-reserve teachers responsible for the education of on-reserve students under Local Education Agreements.

Similar to the regional case studies, the thematic case studies included individuals with similar portfolios to those listed for the regional case studies.

Prospective communities or organisations were contacted by AANDC in writing and subsequently contacted by Donna Cona Inc. to confirm whether participants were interested. Communities wishing to participate worked directly with the consultant to organise the site visit and information sharing. Participants were asked if they were willing to have their interviews recorded. Willing participants' audio files were securely stored electronically, and hand-written notes were securely stored for those not wishing to be recorded. Data was stripped of personal identifiers and securely transmitted to the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) for analysis and interpretation using NVivo 9 Qualitative Analysis Software. Data are stored in accordance with departmental guidelines on data storage, to be destroyed after five years, and are handled as "Protected B"Footnote 11 information. Responses were organised by evaluation questions and open-ended thematic elements.

Concise case study reports were also completed by Donna Cona for each regional and thematic case study, which included community and/or program specific context, as well as relevant data and statistics. A technical report of case study analysis was conducted by EPMRB and reviewed by Donna Cona. - Costing Analysis:

KPMG was contracted to review detailed expenditures data and methodology, comparatively between AANDC and all provincial school districts. This comparison was to develop an empirical appreciation of the level of resources required to implement education programs and services in First Nation schools that are comparable to those in adjacent provincial schools. The study was to examine the most up-to-date financial data available for all districts (2009) and analyse funding formulae used by provinces, and to identify the principles and assumptions that apply to the funding methodologies, and the potential implications for the Department in moving forward under various scenarios. KPMG collected detailed expenditures data from most school districts, including detailed funding formulae. AANDC provided its funding break-downs by category for comparison. - Data Analysis:

A review of the Nominal Roll database was undertaken by EPMRB for fiscal years 2006-07 to 2010-11. Two databases were developed using extracts from raw Nominal Roll data on a per‑student basis. One was designed to assess student progress over time, and the other to contextualize student outcomes with other community factors, such as population, isolation, income, and Community Well-Being Index (CWBI) factors such as community education level, housing, labour market strength and household income. Personally identifying information was stripped from extracted data. Data were analysed to provide an assessment of drop-out frequency and characteristics; progression rates of students through high school; graduation rates and characteristics; and educational outcomes in the context of community characteristics. All data used for this exercise were treated as "Protected B" information. - Document and File Review:

A document and file review was undertaken by EMPRB and included, but was not limited to, Treasury Board Submissions, the Departmental Performance Report, the Report on Plans and Priorities, Budget announcements, previous audits and evaluations, the Education Performance Measurement Strategy, Office of the Auditor General (OAG) reports, annual reports, project files, Regional Health Survey publications, Education Information System documentation, the Final Report of the National Panel on First Nations EducationFootnote 12 and other administrative data. Relevant documents were scanned for content relating to key evaluation questions and the analysis was triangulated with other lines of evidence. - Key Informant Interviews:

A total of 40 interviews were conducted by Donna Cona Inc. with the following key informants: six AANDC HQ, 11 AANDC region, and 23 First Nation organizations. The purpose of key informant interviews was to obtain a better understanding of the results of education programming supported by AANDC and its impact on First Nation and Inuit communities. Key informants further helped to identify other potential key informants and communities for case studies.

Prospective key informants were contacted by EPMRB in writing and then subsequently contacted by Donna Cona Inc. to establish their willingness to participate. Those wishing to participate negotiated a time and interview process with the consultant. Participants were asked of their willingness to be recorded. Willing participant's audio files were securely stored electronically, and hand-written notes were securely stored for those not wishing to be recorded. Data was stripped of personal identifiers and securely transmitted to EPMRB for analysis and interpretation using NVivo 9 Qualitative Analysis Software. Data are stored in accordance with Government of Canada guidelines on data storage, to be destroyed after five years, and are handled as "Protected B"Footnote 13 information. Responses were organised by evaluation question and open-ended thematic elements. - Literature Review:

Members of the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa conducted a "Meta-Analysis of Empirical Research on the Outcomes of Education Programming in Indigenous Populations in Canada and Globally," which included a comprehensive assessment of literature (published and unpublished) over the past 10 years, and emphasized peer reviewed empirical research related to educational outcomes for students in First Nations and other Aboriginal populations in Canada. The purpose of the review was to provide insight on the impacts of policies and programming in education (curricula, investments, governance) on student success, as well as economic integration.

Following this initial analysis, it was determined that a supplementary literature reviewFootnote 14 would be conducted by EPMRB to provide further insight on the following themes:- Jurisdiction and control in First Nation education

- Education systems and second and third level services

- Early childhood education

- Adult learning and higher education

Other sources, such as websites, conference proceedings and working group papers, were also included where they proved useful in providing context or in identifying emerging research and issues. - Surveys:

Surveys were undertaken by Harris/Decima to gain insights from education authorities/managers, principals and Regional Management Organisations beyond what could be obtained with key-informant interviews. A total of 113 surveys were completed.

To maximise confidence in the generalisability of Education Administrator (approximately 600 in total) survey results, a minimum required sample size of approximately 200-225 respondents was necessary. Based on an anticipated response rate of 30 percent, it was decided that EPMRB would attempt to engage contacts from all First Nation communities in Canada to participate. In attempting to produce accurate contact information for all First Nation education administrators, EPMRB was able to gather contact information for 520 of 616 First Nations across Canada. EPMRB contacted all prospective participants in writing and then followed up via telephone to gauge interest in participating. Those agreeing to participate were given the choice to complete their survey online or via telephone. Details were logged and sent to Harris/Decima, who then followed up with participants.

Survey results were compiled by Harris/Decima, stripped of any identifying information and analysed by EPMRB using PASW 18 Statistical software and NVivo 9 Qualitative software for open-ended responses. A total of 16 follow-up interviews were also conducted with respondents who agreed to elaborate on some of the qualitative answers provided in their surveys. Qualitative data from the survey and its follow-up interviews were coded and analysed in a consistent fashion as with case studies and interviews.

In terms of regional representation among the 113 participants, regions were generally represented proportionate to the number of reserves in each, but with Ontario and Alberta somewhat overrepresented and Quebec underrepresented.

2.3.2 Considerations, Strengths and Limitations

Since the evaluation builds upon the critical analysis of existing data, it also favours reductions in the reporting burden on First Nations communities. Reducing the reporting burden for recipients is a key priority for AANDC and for the Government of Canada at large.

This evaluation will further consider AANDC's Sustainable Development Strategy'sFootnote 15 objective of enhancing social and economic capacity in Aboriginal communities through educational programming, with particular emphasis on factors affecting Aboriginal high school graduation rates.

Moreover, the evaluation adhered to AANDC's Policy on Gender Based AnalysisFootnote 16 by analysing multiple variables based on gender.

This evaluation comes at a time when several reforms for First Nations education are underway or being considered, such as "Reforming First Nation Education" beginning in 2008 and actions that will be taken as a result of the National Panel on First Nation Elementary and Secondary Education for Students on Reserve. While this evaluation focuses primarily on outcomes to date, it also discusses priorities moving forward.

Survey Respondent Selection: While every attempt was made to have a broad representative sample of First Nation education managers/directors, it is expected that a degree of respondent bias exists, as selection was not truly random, and those agreeing to participate may or may not have views aligning with those not agreeing to participate, or those we were unable to reach. Additionally, given that respondents were asked to send a survey link to post-secondary students on behalf of the evaluation team, there is no way to know how many students actually received the survey, and no follow-up protocol was available for this group. As only 113 of the target 200 surveys were completed, the minimum sample size needed for statistical validity was not officially met.

Interviewee Respondent Selection: While every attempt was made to have a broad representation of First Nation and Government of Canada viewpoints, it is expected that there could be a degree of respondent bias. Specifically, it is possible that those agreeing to participate could have viewpoints inherently different from those not interested in participating.

AANDC Internal Database Limitations: Data recorded for the Nominal Roll have only recently become reliable insofar as a consistent application of data entry nationally. Thus, this analysis is limited to only 2006-07 to 2010-11 data. Consequently, only five school years of statistics were analysed for trend analysis, and only one full cohort could be legitimately assessed for progression over time (grade 9-12). Additionally, Nominal Roll data are not independently verified and thus, it is not possible to assess the accuracy of the information recorded in the system. It is also important to note that community-based information used to create one of the two data bases are based on Census 2006 figures. While these figures are outdated, it is expected that as this analysis is national, changes in the subsequent six years in all probability would not be significant enough to change observations in the current analysis.

Expenditures Analysis: The most significant issue regarding expenditure analysis was inconsistencies in the way financial data are recorded between districts, between regions and over time. For example, for each funding component of education programming, each region uses different definitions and includes different line items in each category, thus, making legitimate comparisons extremely difficult. Interpretation was impeded by the fact that the expenditures recorded for each provincial district did not correspond to the official regional funding formulae. Additionally, the study was unable to account for all income sources for education authorities, thus, potentially underestimating the available resources. Given these limitations, and the significant complexity of analysing each formula in the context of on-reserve education, more research will be needed to provide a clearer sense of expenditure comparisons.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

EPMRB of AANDC's Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority, and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy, outlined in Section 1.3, and the Quality Assurance Strategy (QAS). The QAS is applied at all stages of the Department's evaluation and review projects, and includes a full set of standards, measures, guides and templates intended to enhance the quality of EPMRB's work.

Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The EPMRB evaluation team was responsible for overseeing all aspects of data collection and validation, as well as composition of the final report and recommendations.

All information from consultants was thoroughly reviewed by the Project Authority (EPMRB) for quality, clarity and accuracy. Subsequently, the consulting firms thoroughly reviewed the analysis of data conducted by EPMRB to ensure their information was well-captured. The Advisory Committee assisted in the development of tools, interpretation of findings and the development of final reports.

In addition, status updates and key findings were regularly provided to EPMRC for strategic advice and direction.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

3.1 Continued Need

Is there an ongoing need for investment in First Nations Education programming?

Finding: This evaluation found that there is a need for continued investment in the Authorities for Elementary/Secondary Education stemming from projected population growth and from the need for significant improvements in student outcomes.

The need for continued investment in Education programming is amply demonstrated by the significant gap in educational opportunities and outcomes between First Nation and other Canadian learnersFootnote 17. Findings in the current study are consistent with observations made in the Formative Evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Program On ReserveFootnote 18 - that the expected growth in the on-reserve population will undoubtedly generate greater needs for ongoing investment in education services and the sustainability of programs and facilities to accommodate this growth. Population projections obtained from Statistics Canada show a projected growth in the population of children on reserve of approximately 15 percent, or an additional 30,000 children (see Figure 1) over the next two decades. This does not include the potential implications of persons relocating to reserves as a result of amendments to Bill C-31Footnote 19 and Bill C-3Footnote 20.

Among the greatest concerns raised by First Nation interview and case study participants were significant ongoing and projected increases in operational costs relative to available resources. It was broadly agreed among most case study and interview participants, both First Nation and government, that there are serious gaps in the ability of First Nation schools to attract and retain teachers and support staff with competitive salaries and benefits, and in the ability to manage increasing costs for programming and infrastructure. There was broad consensus that these issues need to be addressed strategically and expeditiously to ensure improvements in student outcomes.

Text description of Figure 1: Projected Population Growth by Age Category of Interest from 2010 to 2026

This figure is a graph indicating the projected population growth by age category each year during the period of 2010 to 2026. There are three age categories represented by independent lines: 0-18 years, 19-64 years, 65 years and over. The population rates are indicated on the 'y' axis and the years are indicated along the 'x' axis.

The 0-18 age category in 2010 is listed at approximately 175,000 and progresses to 200,000 by 2022. By 2026, the population rate for this age category reaches approximately 210,000.

The 19-64 age category had the most pronounced population growth. The 2010 rate began slightly below 250,000 and consistently progressed at a 30 degree trajectory, ending at just under 350,000 by 2026.

The 65 years of age and older category has a slow growth rate, beginning at approximately 25,000 in 2010 and progressing at a consistent rate, reaching 50,000 by 2026.

As stated in the Report of the National Panel on First Nation Elementary and Secondary Education On ReserveFootnote 21, the lack of a high school education is strongly tied to significant unemployment, high use of social assistance and a high incidence of involvement in the justice system. Given the broad and excessive social costs associated with these elements, coupled with the current rate of graduation (estimated between 25-30 percent on reserve and 35-40 percent for reserve students attending off reserve, according to Nominal Roll data), and the potential for successful First Nation graduates to address projected labour shortages over the next two decades, there is likely a far greater cost associated with status quo than with strategic investments into the future.

Case study and interview participants frequently raised the issue of transferability of skills and knowledge from schools on reserve to secondary schools off reserve. It was noted that a key priority of education programming investment needs to be in ensuring that students in any given grade on reserve are receiving equal quality instruction and transferable knowledge and skills as those in provincial schools to increase the probability of success.

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

3.2.1 Are Education Authority Activities strategically aligned to Government of Canada Priorities?

Finding: Education authority activities are generally aligned with Government of Canada priorities; however, recent major reforms are reflective of the need to better align activities and better ensure improvements in student success.

Insofar as Education Authority activities relate to better education outcomes for First Nation students, there is a clear strategic alignment with government priorities. The Department's approach to ESE, however, was in a state of significant change through the course of the current study and continuing into the coming years based on the need to further refine its activities to be better aligned with strategic outcomes.

Critically, the 2004 Report of the Auditor GeneralFootnote 22 stated that, "The Department has not clearly defined its roles and responsibilities. The way it allocates funds to First Nations does not ensure equitable access to as many students as possible, and the Department does not know whether the funds allocated have been used for the purpose intended." The report recommended that the Department implement a comprehensive strategy and action plan to close the education gap. The 2011 Status Report of the Auditor General, however, noted that while work had begun in response to those recommendations, there was not a consistent approach and it could not demonstrate improvements. The Reforming First Nations Education Initiative was launched in 2008 with a stated target to have 75 percent of First Nation students achieve education outcomes comparable to those of the rest of Canada by 2028.

The Government's continued investments and stated objectives for First Nations education – as outlined in budgets 2011Footnote 23 and 2012Footnote 24 – further demonstrate recognition of the need for strategic changes and innovative planning in order to better align AANDC activities with desired outcomes for First Nation students. Specific recent examples include the formation of the National Panel on First Nations Education; the Economic Action Plan's purported additional $275 million in new spending over the next three years; the introduction of a First Nations Education Act by 2014; the $100 million investment in early literacy and other supports; and the $175 million investment in school renovations.

Additionally, the Reforming First Nation Education Initiative, which received significant praise from Aboriginal and government interview and survey participants, has facilitated significant new funding initiatives through its First Nation Student Success Program and Education Partnerships Program. These initiatives are designed to provide extra support for educators on reserve and to promote greater collaboration with provincial schools, the federal government and other stakeholders to facilitate better student outcomes.

Major revisions in education-related activities reflect a common sentiment expressed by government interview participants in this study – that while AANDC education programming outcomes are aligned with the Government's objectives, its broad activities are undergoing significant reform because outcomes are not improving in a satisfactory manner.

3.2.2 Are the education-related priorities of AANDC aligned with those of First Nations?

Finding: The priorities as stated by First Nation Education Authorities and those of AANDC are aligned insofar as the need to address marked gaps in educational opportunities and success. However, First Nation participants emphasise key priorities in the areas of cultural and language retention as being critical to success, and emphasise the need to recognise key differences in learning needs and the current state of education gaps, rather than simple notions of comparability.

When asked to explain what they saw as the ultimate priority for First Nations education programming, nearly all respondents indicated that it was essential to close the gap in terms of both the opportunities provided and the successes achieved by students. This was seen both as an intervention to address personal, community and economic well-being, and as an opportunity to bring significant numbers of skilled professionals into the labour market.

Additionally, however, it was the broad consensus among First Nation participants that the retention of heritage languages, and learning with culturally-relevant curricula were essential to improving outcomes. Specifically, participants suggested that retaining a strong cultural identity, coupled with knowledge of their history and competence in their heritage language creates a sense of personal belonging within a community, and a stronger sense of self-worth necessary to feel motivated to be successful in school. While there is not an abundance of peer-reviewed literature directly linking culturally-based learning to longer-term educational success, there have been some promising results in short-term goals in language and heritage immersion programsFootnote 25,Footnote 26. Much of the research that exists generally suggests that such programming increases the congruence between school, language, and culture; includes topics of relevance to youth; provides accurate images of both the past and present; improves the self-esteem and pride of Aboriginal youth and increases engagementFootnote 27,Footnote 28.

While internal data from the Nominal Roll is not designed to account for the availability of culturally-relevant curriculum or language immersion programs, what is clear is that students perform more poorly when their language of instruction is different from their language spoken at home. Specifically, when examining progression from one grade to the next, a difference between the instruction and home language was strongly associated with increased time to progress through high schoolFootnote 29. These findings, as well as other research reviewed, suggest the need not only for greater English and/or French proficiency, but also the clear benefits of heritage language retention.

For example, a study of heritage language immersion programsFootnote 30 examined students enrolled in English or French language instruction and either course work or full immersion in Inuktitut. Students in the Inuktitut immersion program showed steady improvement in the heritage language and made gains in English. Students in the English program showed steady gains in English, even though it was not spoken at home. However, they did not have the same proficiency in Inuktitut as peers in the immersion program. Students in the French program showed good progress in that language despite the lack of instructional materials, but their skills in Inuktitut showed the slowest gains of the three groups. Only students in the Inuktitut immersion program had attained a level of proficiency that allowed them to solve complex mental problems in that language. The researchers also noted that personal self-esteem scores at the end of kindergarten were the highest among the Inuktitut immersion students.

First Nation interview and case study participants particularly suggested the need to incorporate traditional forms of learning and communication such as traditional and creative arts; music; dancing; and story-telling, into broader efforts to improve numeracy and literacy. They further suggested that where such learning is present, there is evidence of positive effects insofar as attendance and engagement in the subject matter. Some participants suggested First Nation students need to see themselves in the learning as an engaged actor in the process, and this will facilitate a better identification with the subject matter, a stronger sense of identity and pride, and thus, a motivation to attend and do well in school. An example of a holistic learning process of this kind involves the math teacher engaging students in the rhythm of algebraic equations, for example, with physical movements as they take in, understand, and internalize the mathematical learning so the math is integrated within the 'whole' person.

First Nation participants also suggested that their students learn much better with hands-on opportunities. They indicated the need to move beyond classroom instruction and to offer more applied learning relevant to their culture, as well as extra-curricular activities. In this way, while the broad desired outcome of success is consistent between First Nation education administrators and AANDC programming, the notion of comparable opportunities may be somewhat of an oversimplification. The opportunities that should be comparable, according to all participants, are the availability of quality teaching in quality schools, opportunities for broad educational growth and development, opportunities to pursue post-secondary, and to be competitive in the labour market. Where this becomes more complex is that many First Nation participants see the specific opportunities for learning as very different between First Nation and non-First Nation learners. Specifically, participants suggested a significant divide between a holistic approach to learning versus the dominant approach of focussing on the mental processes, with little to no attention given to the spiritual, emotional, and physical learning/intelligence, which participants suggested cannot be separated from the mental processes in a holistic model for education.

This is particularly apparent in the expressed need for more culturally-relevant learning in the off-reserve schools systems. The concern focussed on the limited success among First Nation students attending off-reserve schools. The First Nation students' inability to see themselves in the subject matter and a general lack of welcoming and culturally relevant learning environments lead to an array of negative outcomes for many students, according to participants. Therefore, First Nation participants indicated that opportunities, while needing to be equitable, needed to be tailored to the needs for First Nation students and their families.

Caution was also raised by respondents from all groups around the concept of comparability. It was particularly noted that currently First Nation students lag far behind their non-First Nation counterparts in overall performance – particularly evident in the rates of graduation and drop-out. Additionally, it was noted that there is a degree of resistance to the education system among some parents, largely linked to trauma associated with the residential schools system. Thus, participants were clear in the notion that comparability should not imply receiving the same services; rather that starting at a significantly deficient point, First Nation communities and students will need significantly more supports than their counterparts.

3.3 Role of the Federal Government

Is the current role of the Government of Canada legitimate, appropriate and necessary for the improvement of First Nations education success?

Finding: The role of the Government of Canada in ESE programming is generally appropriate; however, policy changes with respect to service delivery and local operational control may have implications on this role in the future.

All AANDC participants stated that the role of the Government of Canada, and specifically of AANDC, was appropriate with respect to ESE programming. The Reforming Education Initiative was frequently cited as the ongoing mechanism of the Government's prioritising its support of First Nations to better ensure positive student outcomes. There were also references made to the Government's stated notions that First Nations youth represent an enormous potential for the current and future labour market, and that currently the potential is not being met.

Similar to issues discussed in Section 3.2.1, however, the precise role of the Government has the opportunity to evolve given the major reforms underway, and the desire to increase First Nation control of First Nations education. While there was no clear sentiment expressed by interview participants of the broad role of the Government needing to change, as discussed in Section 4.4, issues with respect to jurisdiction and control, as well as evidence of a need for broader education initiatives from early childhood, and potentially innovative structural changes designed to better meet learning needs, have all been raised. Evidence from this study, and that of the National Panel on First Nations Education, have pointed to key aspects needing change, which may have implications on the Government's current specific roles in program design and delivery.

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

4.1 Achievement of Intended Outcomes

To what extent have intended outcomes been achieved as a result of AANDC programming?

Finding: It is the finding of this evaluation that the intended outcome of comparable education opportunities and results to the Canadian population is not being achieved.

Evidence from case studies and key-informant interviews is consistent with notions in the National Panel on First Nations education that suggest First Nation students do not have comparable education opportunities to other Canadians. Issues related to this lack of comparable opportunities are discussed in detail in sections 4.3 and 4.4. Without comparable opportunities, there can be no reasonable expectation of comparable outcomes, and it is clear from the evidence below that neither the opportunities nor outcomes are comparable.

As shown in Figure 2 and as discussed in the Formative Evaluation of ESEFootnote 31, data from Statistics Canada shows that while the rates of Aboriginal Canadians with a high school diploma or greater living off reserve have typically been about 20-30 percent lower than the Canadian average, the gap is slowly narrowing. The same cannot be said of those living on reserve. Generally speaking, the on-reserve population had only seen a five percent increase in the proportion of individuals with a high school diploma or higher on reserve – from about 25 percent to 30 percent of adults under 25 between 1996 and 2006.

Text description of Figure 2: Proportion (%) of individuals by Age Group, Status (Aboriginal Off Reserve, Aboriginal On Reserve, Non-Aboriginal), Gender, and Census Year with a High School Diploma or Higher

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a high school diploma or higher by gender, by status, by year, and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal Off-reserve and Aboriginal On-Reserve) by gender, year (1996, 2001 and 2006) and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a high school diploma or higher is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 80% of the Non-Aboriginal population (78% of males and 83% of females) had a high school diploma or higher in 1996, compared to approximately 52% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (51% males and 53% females) and 33% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (32% of males and 35% of females).

In 2001, approximately 83% of the Non-Aboriginal population (80% of males and 85% of females) ages 20-24 had a high school diploma or higher, compared to approximately 56% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (54% males and 85% of females) and 37% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (36% of males and 41% of females).

In 2006, approximately 87% of the Non-Aboriginal population (85% of males and 89% of females) aged 20-24 had a high school diploma or higher, compared to approximately 67% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (65% males and 69% females) and 38% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (36% of males and 42% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 81% of the Non-Aboriginal population (78% of males and 83% of females) had a high school diploma or higher in 1996, compared to approximately 56% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (54% males and 59% females) and 39% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (41% of males and 43% of females).

In 2001, approximately 84% of the Non-Aboriginal population (82% of males and 86% of females) aged 20-24 had a high school diploma or higher, compared to approximately 64% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (61% males and 67% of females) and 46% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (43% of males and 49% of females).

In 2006, approximately 89% of the Non-Aboriginal population (85% of males and 92% of females) aged 20-24 had a high school diploma or higher, compared to approximately 73% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (71% males and 75% females) and 47% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (44% of males and 51% of females).

Examining Nominal Roll data for the years subsequent to 2006, there appears to have been little to no improvement. The drop-out ratesFootnote 32 have remained consistent, although significant improvement was noted in the pre-grade 11 cohorts. Being above the average age for any given grade was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of drop-out, and the likelihood becomes stronger the older the student. Generally speaking, the drop-out rate is higher among females before grade 9; and roughly even between males and females for higher grades. Being older than average within a grade, however, has a far greater impact on the likelihood of males to drop out than of females. In particular, males over 18 are far more likely to drop out and this trend becomes progressively sharper with ageFootnote 33.

The average age of a school-aged student dropping out is 17.5 years old and as shown in Figure 3, the drop-out rates increase sharply with age and overall the rate is high, from about five to eight percent on average in any given school year for students between grade 9 and 12, and much higher for older aged students. It is important to note that these figures reflect only official and logged drop-out (a student who was present in the previous year and is not enrolled the following year but did not graduate) thus, the actual figure may be underestimated.

Text description of Figure 3: Drop-out Rates by Age Collapsed across 2006-07 to 2010-11

This graph represents the drop-out rates by age collapsed across 2006-07 to 2010-11. The 'y' axis measures the percentage of withdrawals that are greater than zero, whereas the 'x' axis measures "leavers' age". The drop-out rates increase sharply with age, beginning at 15 years old. Between age 20 and 53 the rate remains above 10% and does not surpass 20%. Age 53 drop-out rates rise slightly to 21%, but decrease to around 17% by age 55. The drop-out rate significantly increases to 23% by ages 57-58.; The rate further peaks at 39% for 60 year olds and dips to the lowest point (approximately 9%) since the teenage demographic, at age 62. From that point the drop-out rate experiences another sharp increase, peaking at the highest point in the graph, approximately 43% for 67 year olds. Finally, the graph depicts one final drastic dip, hitting 10% in the 69 year old age bracket.

In examining those that dropped out, approximately 23 percent eventually returned, but only 13 percent of those who returned and reached their final year actually graduated.

The rate of graduationFootnote 34 has shown virtually no improvement at approximately 34 percent overall. Looking only at school-aged individuals (21 or younger), the rate has remained steady at 37 percent. The average age at graduation is 20 years old and this has not changed over time.

Examining regional trends, there was a significantFootnote 35 improvement in Ontario from about 23 percent to 30 percent and this was particularly pronounced for female students, from about 23 percent to 34 percent. Atlantic region had the highest rate of graduation overall and also showed significantFootnote 36 improvement from about 55 percent to 65 percent.

The graduation rate was higher for females (33 percent) than males (30 percent), and while the percentage difference appears small, it represents a difference of about 200 students per year and is significant.Footnote 37 This trend, however, reverses with age with males tending to have a higher likelihood of graduating among cohorts over 21 – a trend that increases with age.Footnote 38 Thus, the data appear to suggest that older males are more likely to drop out than females and more likely to graduate. In other words, among older cohorts, male students in their final year will more often either graduate or drop out, whereas female students, while less likely to graduate, are also less likely to withdraw.

For the cohortFootnote 39 examined in this study, only 44 percent progressed through grades (to the start of grade 12) within the expected time frame. Nearly a third of these students repeated one grade and 15 percent repeated two grades. More than 600 students in this cohort repeated three or more times within the five years examined. There is no obvious gender difference in these trends. Importantly, education administrators surveyed in this study suggested schools were generally well-equipped to prepare students to transition through earlier school years, but much less so in later years, and certainly there was very little optimism about the ability of schools to facilitate transitions to post-secondary or the labour market.

When speaking with educators, there was a general sentiment that while there is little to no improvement in raw outcome figures, they have noticed some improvement in attitudes toward education in their communities, among their leadership and among students. They further indicated that it will take time for these changes to translate into obvious results.

Survey participants suggested that where there was strength in the quality of learning, it came mostly from the dedication of staff and innovative programming at the school level. With respect to off-reserve schools, issues mostly concerned the lack of culturally-relevant learning, the tendency to push students through the system without adequate preparation, and issues with transferability of knowledge from on- to off-reserve school systems (mostly from elementary to secondary).

4.2 Program Influence on Collaborative Engagement and Networks

To what extent has the program influenced collaborative engagement and collaborative networks to facilitate education and skills development?

Finding: Continued work is needed to better facilitate constructive engagement and collaborative networks between First Nation education authorities, and where appropriate, with provincial governments or other organisations, and there is evidence that AANDC programming is improving in this regard.

Partnerships were said to be integral to future feasibility of a strong First Nations education system, according to participants from all groups. There were key examples from First Nation representatives of partnerships with larger organisations and neighbouring First Nations where collaboration was highly beneficial. It was noted that AANDC must support this type of cooperation in its programming and incorporate partnership development in its support to education programming – which was noted as beginning to improve in recent years with the Education Partnerships Program.

For example, communities that worked together on coordinated transportation, or shared social services, such as social workers and special needs specialists, were noted as seeing improvements in this regard in recent years. Partnerships with mainstream school systems also support the inevitable transition from band-operated schools to public schools off reserve.

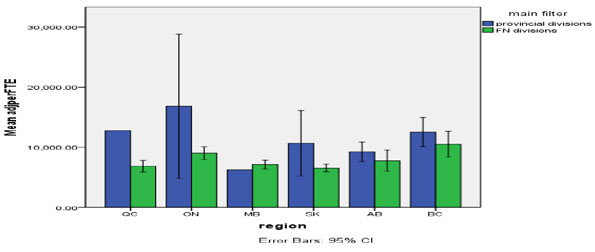

Support from the tribal councils and bands was also seen as crucial. There are varying degrees of involvement in education via the leadership, but ultimately First Nation participants viewed their engagement as highly valuable when it happens. Some noted extensive efforts by their band and/or tribal council to facilitate cooperation and the availability of better services, such as school psychologists and recreational staff. There was certainly a sense that leadership needs to take an active role in encouraging students to attend school and succeed through a combination of: facilitating better labour market opportunities locally; promoting labour market opportunities broadly; acknowledging and encouraging students for their efforts and success; speaking directly to students at general assemblies periodically; and lobbying for more effective programming and better resources.