Archived - Special Study: Evolving Funding Arrangements with First Nations

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: November 2011

Final Report

Abstract: This document provides the final report outlining possible directions and approaches available to evolve the current funding arrangements with non-self-governing First Nations toward a possible increased use of grants where appropriate and desirable.

PDF Version (1,787 Kb, 82 Pages)

Table of Contents

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Introduction

- 3. Background

- 4. A Conceptual Framework for this Study

- 5. Accountability relationship

- 6. Flexibility and Equity

- 7. Performance and Reporting

- 8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Annex A: References

- Annex B: Miawpukek Grant Agreement - why is it appropriate as a baseline for the Model Grant Agreement?

1. Executive Summary

"The best approach may be not to look for a single model that could be applied, but to take elements from each that seem to work well and that could be adapted to the unique requirements of Aboriginal government funding."-Funding Arrangements for First Nations Governments: Assessment and Alternative Model. Report prepared for AANDC. Peter Gusen, February 2008 [Note 1].

1.1 Background

The Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive at Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) commissioned Donna Cona to conduct a special study of AANDC's shift to increasing the use of grants in its funding arrangements with non-self-governed First Nations (FNs). In initiating this shift, the department is determined to address key shortcomings identified by a number of past reports by the Auditor General and by various commissions and studies and to take advantage of opportunities available – some of which were already identified in previous studies and reports, others which would become available through further research, analysis and consultation.

The objectives of this Special Study were two-fold:

- To determine to what extent, under what circumstances and through use of what conditions (if any) the use of grants to fund services provided by FNs may be appropriate for the department in furtherance of its and the government's policy objectives respecting First Nations, Aboriginal peoples and Northerners; and

- To establish what mechanisms, techniques and approaches can be used within or in conjunction with funding arrangements (like grants) that provide additional flexibility to FNs in respect of the use of federal funding, while at the same time:

- Reducing the risk of non-performance or default to both the department and the FN community;

- Enhancing accountability of FNs in a way that effectively "pushes" accountability closer to the community while achieving effective accountability between recipients and their stakeholders and between the Minister and Parliament, and ultimately to Canadians;

- Reducing the administrative and reporting burden on FNs recipients;

- Ensuring that adequate planning, performance and other program-related data is made available to the department in a timely and effective manner in order to ensure that the department can effectively "measure what matters", discharge ministerial accountability obligations to Parliament and plan ahead for evolving a more effective funding and accountability regime in its relationships with FNs.

- Reducing the risk of non-performance or default to both the department and the FN community;

The study focused primarily on non-self-governing First Nations; moreover, as departmental officials and various reports and discussion papers estimate, only some 10-15% of all FNs (or some 60 to 100 high-performing FNs) are likely to qualify for a shift to a grant-based funding arrangement. Many of these FNs are already in fairly flexible, block contributions.

The study was conducted through a documentation and literature review; discussions with officials and experts; and extensive analysis.

1.2 The study framework and its key underlying principles

The diagram attached captures the key elements and the focus of this study.

The following are the "global" assumptions and key principles behind this study framework:

- The department wishes to explore the increased use of grants in funding program services delivered by First Nations (FNs) to their members in the belief that this may be beneficial to both department and FN recipients and may represent a step toward delivering positive responses to long-standing recommendations in the RCAP Report, the Auditor General's various reports on funding to FNs and calls by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and other Aboriginal organizations for deep change in the fiscal relationship between the Federal Government and FNs.

- AANDC will favour the use of grants whenever appropriate and desirable, taking into account the differences that exist in the risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances characterizing FNs. "Appropriate" and "desirable" refer to those FNs whose risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances established through such instrumentalities as the General Assessment or certifications by agreed-upon third parties recommend and warrant the use of grants. It may be realistic to expect that only 10-15% of the over 600 FNs currently funded through contributions may qualify, at least in the first "wave". A departmental strategy to bring new FNs for consideration in subsequent waves (e.g., through capacity development work and "closing the gap" funding) will need to accompany this shift.

- The use of grants will not replace, but will continue to complement, the other types of funding agreements (e.g., contributions for project-based funding), whose use will continue as circumstances warrant.

- The Miawpukek Grant Agreement provides an appropriate departure point ("baseline") in the evolution to increased use of grants. As such, Miawpukek serves as a starting point on a journey toward a new Model Grant Agreement (MGA) that can be tailored to accommodate differences in the risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances characterizing FN. A description of the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and a rationale for its use as a baseline/ departure point is provided in Annex B.

- The new Model Grant Agreement should provide a fiscal transfer vehicle for both a single department and multiple departments as funders, based on the principle of "one community, one agreement" whenever that is possible and desirable from both a funders' and FN's perspective.

- To ensure streamlined administration, where multiple funders are involved, the MGA should be administered through a "single window", with AANDC acting as the point department and coordinator.

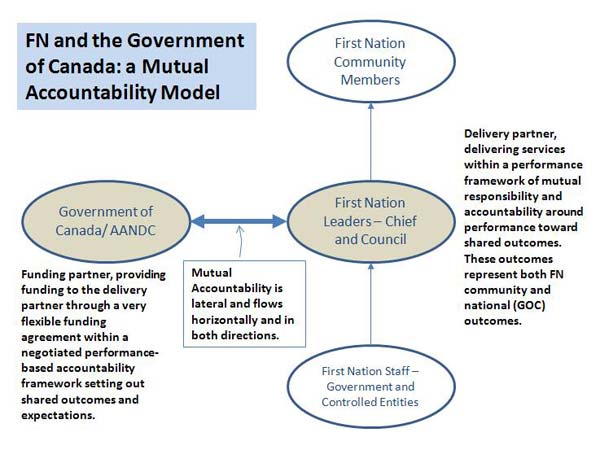

- Finally, the MGA should establish an accountability relationship between funders and FN that provides more balance and symmetry through an increased "two-way" flow between funders and FN. As such, a desirable end-state would be to establish a "reciprocal" or "mutual" accountability relationship, with flows in both directions.

The search for, analysis and presentation of these additional provisions is organized into four categories; these categories are actually the four thematic quadrants shown in the Conceptual Study Framework diagram shown. They are:

Description of figure: Conceptual Study Framework Diagram

The diagram "Evolving AANDC Funding Arrangements: A Conceptual Framework" captures four categories which surround a central block representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and point to it with relational arrows. The four categories encompass the keys additional provisions to build upon the Miawpukek Grant Agreement towards the development of a new ‘Model Grant Agreement' represented by a text scroll icon. The four categories are:

- Accountability Relationship: A beige text box appears beside this label, and contains the following text: "AANDC/HC, Canadian and international practices and approaches that create a healthy accountability relationship while enhancing accountability." A relational line connect this box with the central block representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement. The arrow points to a specific block of text inside the Miawpukek Grant Agreement block which reads, "Other accountability and Performance Measurment enhancement procedures." Below this relational arrow is the following text: "Question: What practices, techniques, instruments and approaches could be considered to help create a healthy accountability relationship and enhance accountability (from FN to members, from FN to Federal Government, from Federal Government to FN)?"

- Flexibility and Equity: Below this label is a beige box labeled "Higher-flexibility Financial Arrangements" which features four quadrants. The four quadrants are "Federal to P/T Transfers" (Transfers from the Federal Government to Provinces and Territories), "Federal to Municipal Transfers" (the Gas Tax Fund a conditional grant to municipalities), "Self-Government Transfers" (Nisga'a and Tsawwassen Final Agreements), and "Provincial-local Transfers" (transfers from Provinces/Territories to Municipalities (Alberta, Nova Scotia)). Below the beige box is the following text: "Question: What provisions, practices, techniques, instruments and approaches could also be considered to help increase flexibility to FN in the use of funding and to advance "equalization," "increased capacity" and "closing the gaps" outcomes in the application of the funding?"

- Performance and Reporting: The third section sits to the right of the centre block representing the Model Grant Agreement built from the Miawpukek Grant Agreement. A beige text box reads "AANDC/HC, Canadian and international practices, techniques and approaches on performance-based reporting and practices and means to reduce administrative and reporting burden." A relational arrow connects this text box and points towards the center block. The arrow ends on a section of text in the center block of the diagram which reads "Additional administrative and reporting burden reduction provisions." Above the relational arrow is the following text "Question: What practices, techniques, instruments and approaches could also be considered to help increase reporting focus on program results and outcomes, while reducing administrative and reporting burden on FN?"

- Eligibility and Conditionality: Above this category is a beige text box which reads "Other existing departmental Grant, AFA, FTP, and Contribution Agreements." A relational arrow connect this text box with the centre block. The arrow points to a text box within the centre block which reads "Additional eligibility and assurance provisions." To the right of the relational line is the following text: "Question: What provisions and practices could be considered in the eligibility and conditional aspects of the grant in order to provide the minimum necessary and adequate assurance of performance and funds management in light of risk profile, capacity and circumstance differences among FNs?"

A highlighted text box points to the entirety of the center block which contains the following text: "Target: A model Grant Agreement that can be tailored to accommodate a range of differences in FN risks, capacities and circumstances."

Finally there is an unconnected text box which outlines the Key Assumptions, which are:

- AANDC will favour the use of grants whenever appropriate and desirable.

- The Miawpukek Grant Agreement provides an appropriate departure point ("baseline") in the evolution to increased use of grants and the development of a Model Grant Agreement.

- Accountability relationship (recasting the accountability relationship with FN);

- Flexibility and Equity (providing added recipient flexibility when appropriate while ensuring that adequate funding flows to those areas that need it most, through for instance, "equalization", "capacity-building, "closing the gaps" and other targeting approaches);

- Performance and Reporting (shifting and strengthening the focus of reporting to performance-based reporting while reducing the administrative and reporting burden in accordance with recipient capacity and risk involved); and

- Eligibility and Conditionality (ensuring, through rigorous up-front assessments, that adequate eligibility provisions and controls and assurance are in place, commensurate with recipient capabilities, capacity and risk, to manage the funding agreement with appropriate probity, openness and transparency).

1.3 Key Findings and conclusions

1.3.1 Policy trendlines

It is difficult to escape the perception that there is a general convergence in the current policy discourse around a sense (if not yet a fully-formed consensus) that the ultimate state of the fiscal relationship with First Nations may involve a departure from the increasingly challenging domain of policy- and administrative-procedures-driven grants and contributions, and toward something more akin to statutory, formula-driven funding that characterize F/P/T transfer payments.

This tenor of the policy conversations goes back to Penner, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) and more recently the Blue Ribbon Commission report. While no federal policy statement or intent could be found that clearly articulates the need to move to more formula-based transfer payment regimes and to increase the use of grants with non-self-governed FNs, this approach represents an unmistakable evolution in that direction.

Trend line in the Federal Government to First Nations Funding Arrangements - Diagram

Description of figure: Trend line in the Federal Government to First Nations Funding Arrangements

The graph depicts a large arrow representing the trend line which flows diagonally from the lower right to the upper left. It intersects multidirectional arrows in an X and Y axis arriving at a beige circle labeled "Statutory F/P/T/local Transfer Payments."

The bottom of the trend line is labeled "An unmistakeable policy trend line…" Within the trend line is a series of labeled beige circles with arrows pointing to the following one to the left. In the lower quadrant of the X axis to the right of the Y axis – moving along with the trend arrow from right to left – are beige circle labeled "Other (non-block) contributions" which has an arrow pointing to another beige circle labeled "Block contributions".

At the intersection of the X and Y axis is a beige circle labeled "Miawpukek Grant Agreement" which has an arrow pointed to the next beige circle which rests in the quadrant above the X axis and to the left of the Y axis. This beige circle is highlighted and labeled "Model Grant Agreement (our target) and has an arrow pointed to the next beige circle which is labeled "Self-government funding Agreements (SGFA)" whose arrow points to circle at the end of the trend line ("Statutory F/P/T/local Transfer Payments.")

Defining the X-Y axis are some text bullets at the ends. At the top of the Y axis:

- Formula-based, non-discretionary driven by community and equalization goals

- Extensive flexibility in the use of funding

At the bottom of the Y-axis:

- Discretionary funding driven largely by the principal's policy goals

- Limited flexibility by the use of funding

At the left end of the X axis:

- Mutual accountability relationship

- Community-focused accountability and reporting

On the right end of the X-axis:

- Principal-agent accountability relationship

- Principal-driven accountability and reporting

A move to increased use of grants would be a positive response to findings, conclusions and recommendations put forth in many of the reports and studies reviewed and would be consistent with the general policy trend toward a fiscal relationship that deals with the Aboriginal communities as a level of government in the Canadian polity.

1.3.2 Provisions to be considered in the new Model Grant Agreement (MGA)

The additional provisions we offer for consideration for inclusion in the structuring of the MGA and, implicitly, in the fiscal relationship with grant-qualifying FNs, are outlined in the diagram below. They are organized based on the Conceptual Study Framework outlined earlier.

Possible additional provisions in the Model Grant Agreement (MGA) - Diagram

Description of figure: Diagram of the Possible additional provisions in the Model Grant Agreement (MGA)

The diagram captures four categories which surround a central block representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and point to it with relational arrows. The four categories encompass the keys additional provisions to build upon the Miawpukek Grant Agreement towards the development of a new 'Model Grant Agreement’ represented by a text scroll icon. The four categories are:

1. Accountability Relationship: Beside the label are the following text bullets:

- A more mutual conception of the accountability relationship between FN and other levels of government, including the federal government.

- Strengthening of the local accountability relationship – from FN council to members;

- Local (Community) Ownership: The FN community essentially owns, through its community plan and leadership on service provisions and development strategies, plans and policies, its service provision and development agenda.

- Accommodating the evolving nature of the accountability relationship between the FN and the rest of Canada in general and the federal government in particular.

- Development and strengthening of FN governance and accountability support and assurance institutions within the Aboriginal community; and

- More alignment harmonization and coordination between funders focusing on shared concern for community outcomes and results.

- Through a Shared Management Agenda (SMA), improve management of resources and decision-making in support of community results.

There is a relational arrow connecting the above-mentioned text bullets to a text box inside the central block (representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and the Model Grant Agreement.) This text box reads: "Other accountability and Performance Measurment enhancement procedures."

2. Flexibility and Equity: Below the label are the following text bullets:

- Funding terms of five to ten years, allowing genuine flexibility and long-term community planning.

- Fairness: AANDC funding to bands or tribal councils to meet a double fairness test – fairness among regions, and fairness within a region among bands or tribal councils.

- Clarity and predictability in funding policies and stability of payments, both for the federal government, which must budget the expenditure, and the recipients, which must have a degree of revenue security to plan their activities. Program operation and outcomes that are clear (transparent) to the recipient authorities, their community members and the general public.

- Responsiveness to changes in recipient’s financial situation and flexibility to accommodate changes in arrangements to allow for evolution in the recipient’s scope of responsibility and capacity to manage.

- Sound incentives for the recipient to promote economic development, expand revenue sources, address social issues, and foster self-sufficiency and increased efficiency in the delivery of services to the community members through aggregation, use of alternative arrangements, etc.

- Reflection of special circumstances and distinct "needs" in some recipients’ communities.

- Full integration of all programs and services of AANDC, with the capacity to include all federal government programs and services.

There is a relational arrow connecting the above-mentioned text bullets to a text box inside the central block (representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and the Model Grant Agreement.) This text box reads: "Additional flexibility and equity-enhancing provisions"

3. Performance and Reporting: To the left of the label are the following text bullets:

- Use of performance reviews by either the department and/or independent, culturally appropriate third-parties.

- Requirement for a performance-based community plan and performance management framework.

- An annual results-based report to the community and the Government of Canada using the community plan and the shared performance management framework. The report could take the form of a Report Card

- Use of alternative reporting and review and adjustment vehicles such as round-table performance reviews.

- Use of automated "continuous reporting"/"continuous assurance" with FN communities that are relatively well-equipped with information technology skills, tools and infrastructures.

There is a relational arrow connecting the above-mentioned text bullets to a text box inside the central block (representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and the Model Grant Agreement.) This text box reads: "Additional administrative and Reporting burden reduction provisions."

4. Eligibility and Conditionality: Above this label reads the following text "Out of scope for this study. Forms the object of another Special Study by Orbis."

Above this text is a relational arrow connecting the above-mentioned text bullets to a text box inside the central block (representing the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and the Model Grant Agreement.) This text box reads: "Additional eligibility and assurance provisions."

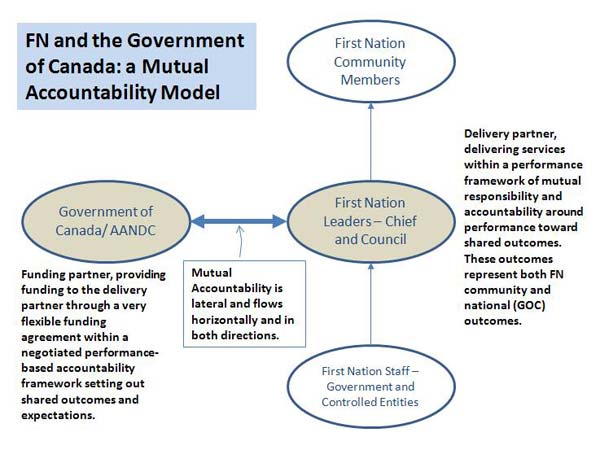

1.3.3 A Possible Accountability, Performance and Reporting Model

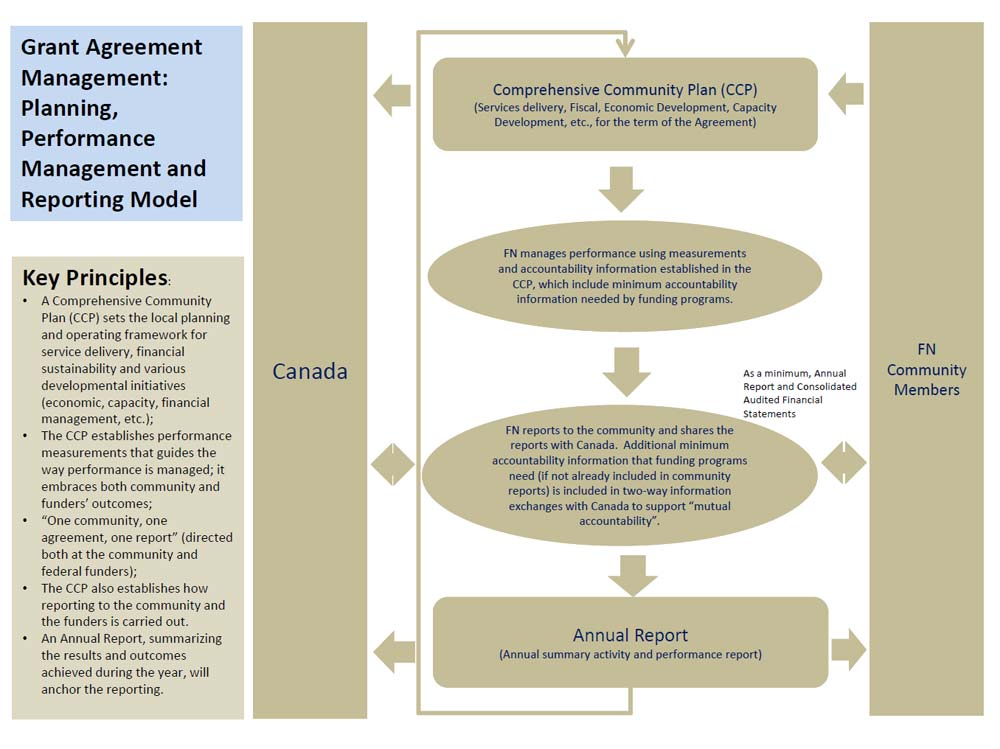

Applying the provisions offered above, the diagram below captures some of the possible functional components, processes and mechanics associated with the implementation of an Accountability, Performance Management and Reporting Model in relation to the Model Grant Agreement.

1.3.4 How would qualifying FNs benefit from the granting regime provided by the MGA?

It is expected that qualifying FNs (most of which are already in relatively flexible contributions agreements) would perceive the following features provided by the MGA as particularly attractive:

Grant Agreement Management: Planning, Performance Management and Reporting Model - Diagram

Description of figure: Grant Agreement Management: Planning, Performance Management and Reporting Model - Diagram

The diagram captures the key principles associated with the implementation of an Accountability, Performance Management and Reporting Model in relation to the Model Grant Agreement.

The diagram is composed of two rectangular columns on the outside left and right. In the middle are a number of labeled ovals and arrows illustrating the relationships between the various elements.

On the left is a tall column labeled ‘Canada' and the other on the right is labeled ‘FN Community Members.' In between them are blocks and ovals representing different aspects of the relationship. Moving from top to bottom they are:

- Comprehensive Community Plan (CCP) block: This rectangle contains text which reads "Comprehensive Community Plan (CCP) (Service delivery, Fiscal Economic Development, Capacity Development, etc., for the term of the Agreement)." A relational arrow illustrates that this Plan is informed by the ‘FN Community Members'and another relational arrow connects the report to ‘Canada'. There is also a relational arrow pointing down to the oval below it;

- This oval contains text that reads, "FN manages performance using measurements and accountability information established in the CCP, which include minimum accountability information needed by funding programs." Below it is a relational arrow which points to the following oval below it;

- This oval contains text that reads, "FN reports to the community and shares the reports with Canada. Additional minimum accountability information that funding programs need (if not already included in community reports) is included in two-way information exchanges with Canada to support mutual accountability." This oval is flanked on each side with a multidirectional arrow. On the right side between the oval and the ‘FN Community Members' and the multidirectional arrow is a block of text which reads "As a minimum, Annual Report and consolidated financial statements". The oval also has a relational arrow sitting beneath it pointing towards the "Annual Report" block beneath it;

- Annual Report block: This block contains text which reads "Annual Report (Annual Summary Activity and Performance report)". It is flanked on each side by arrows pointing towards the ‘Canada' and ‘FN Community Members' blocks. There is also an arrow which connects this block with the ‘Comprehensive Community Plan (CCP)' block.

There is also on the left a text box with the heading ‘Key Principals' listing the following principals:

- A Comprehensive Community Plan (CCP) sets the local planning and operating framework for service delivery, financial sustainability and various developmental initiatives (economic, capacity, financial sustainability and various developmental initiatives (economic, capacity, financial management, etc.);

- The CCP establishes performance measurements that guides the way performance is managed; it embraces both community and funders' outcomes;

- "One community, one agreement, one report" (directed both at the community and federal funders);

- The CCP also establishes how reporting to the community and the funders is carried out;

- An Annual Report, summarizing the results and outcomes achieved during the year, will anchor the reporting.

- Shift from contribution (paternalistic, conditional) to grant (collaborative, trust): This is likely to have significant moral and psychological benefits for the community. It would likely be seen as recognition of a good record of community leadership and performance and an expression of trust in the capacity of the community to manage its own affairs. This may also translate in a better reception by capital markets and other investors.

- No audit by the Minister: This translates in less administrative hassle for the FN community.

- Significantly lighter reporting regime: This also translates into less administrative hassle.

- Better accountability from the federal government to the FN community (mutual accountability relationship): This would create a better appreciation in the FN community of how funding decisions are made and will ultimately result in fewer surprises and more predictability in the evolution of funding policies affecting FN communities.

- Less focus on compliance and more focus on performance: This would be a very welcome shift in the accountability relationship and would be seen as a positive response to long-standing complaints by FN organizations and communities that too much time and energy is spent on compliance reporting and not enough on substantive performance-related issues.

- A clearer path to government-to-government-like fiscal arrangements: The FN community would be able to see a clearer and les encumbered path to possible next stages in its fiscal relationship with the federal government. It may also provide added impetus to less well-performing communities to strive to qualify as grant recipients.

1.4 Recommendations

We offer four recommendations in furtherance of the findings and conclusions articulated in this report:

- Engagement of Aboriginal forums: That AANDC engage the appropriate Aboriginal forums in the development of a model community plan, a model shared management agenda and a model performance management framework to serve as essential implementation companions to the MGA. While a lot of work has already taken place in the Aboriginal community, little recent progress is apparent. These would be adaptable to a wide range of FN community circumstances.

- Engagement of Aboriginal institutions and organizations: That AANDC engage the appropriate Aboriginal institutions and organizations in developing appropriate performance review and accreditation/certification frameworks for use in the application of the MGA. These would allow increased reliance on culturally appropriate third-party actors in the administration of the MGA. Again, these should be adaptable to a wide range of FN community circumstances.

- Engagement of key federal funders That AADNC engage other principal federal funders (e.g., HC, HRSDC, CMHC) in the development of the MGA and its companion elements and in efforts to achieve increased alignment and harmonization in funding practices, terms and conditions targeting the same recipients. Ideally, the MGA should be crafted in a way that would allow it to serve as an aggregate funding vehicle for a number of key federal funders.

- Engagement of program managers: Finally, it is recommended that AANDC make an effort to engage program managers in the work associated with the development of the MGA. Resistance to a shift to grants is likely to come primarily from program managers; as such, such a move would help to allay their concerns and ensure that legitimate program accountability needs are factored into the MGA.

1.5 Additional Research

We suggest the following areas for further research. They support the development of the MGA and its supporting elements and help in the implementation of the recommendations offered above:

- Model community plan, model shared management agenda and model performance management framework.

- Best practices in results and outcomes-based reporting.

- Incentive practices and mechanisms to stimulate the growth of own source revenue and community-driven initiatives in economic and social development, in aggregation and other approaches that advance the FN communities' search for efficiencies in the delivery of services.

- The application of principles of equalization and need-specific targeting in the MGA

- The treatment of capital funding and institutional options such as a separate capital infrastructure investment fund.

2. Introduction

2.1 This document

This document is the final report of the Special Study on Evolving Funding Arrangements. A number of salient facts are in order:

- The finding, conclusions and recommendations provided are based on a literature and document review, limited discussions with officials and experts and analysis;

- The report focuses on non-self-governing First Nations (FNs); moreover, as departmental officials and various reports and discussion papers estimate, only some 10-15% of all FNs (or some 60 to 100 FNs) are likely to qualify for a shift to a grant-based funding arrangement. Many of these FNs are already in fairly flexible, block contribution arrangements.

2.2 Objectives and Approach for this Study

The objectives of this Special Study are two-fold:

- To determine to what extent, under what circumstances and through use of what conditions (if any) the use of grants to fund services provided by FNs may be appropriate for the department in furtherance of its and the government's policy objectives respecting First Nations, Aboriginal peoples and Northerners; and

- To establish what mechanisms, techniques and approaches can be used within or in conjunction with funding arrangements (like grants) that provide additional flexibility to FNs in respect of the use of federal funding, while at the same time:

- Reducing the risk of non-performance or default to both the department and the FN community;

- Enhancing accountability of FNs in a way that effectively "pushes" accountability closer to the community while achieving effective accountability between recipients and their stakeholders and between the Minister and Parliament, and ultimately to Canadians;

- Reducing the administrative and reporting burden on FN recipients;

- Ensuring that adequate planning, performance and other program-related data is made available to the department in a timely and effective manner in order to ensure that the department can effectively "measure what matters", discharge ministerial accountability obligations to Parliament and plan ahead for evolving a more effective funding and accountability regime in its relationships with FNs.

- Reducing the risk of non-performance or default to both the department and the FN community;

2.3 Approach and Methodology for this Study

We employ the following approach and methodology to meet the objectives of the study:

- Documentation and literature review;

- Preparation of a Preliminary Conclusions based on the document and literature review to facilitate early testing of assumptions, shape interviews and secure early feedback;

- Selective interviews with AANDC and HC officials, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations (e.g., FN Financial Management Board personnel) and funding arrangements and accountability experts;

- Draft Report, where we presented draft key findings and conclusions and seek feedback, comments and suggestions from AANDC personnel and others; and

- Preparation of the Final Report (this report), where we incorporate final findings, conclusions and the feedback and comments received in relation to the Draft Report.

3. Background

3.1. First Nations: a disaggregated view

Before proceeding further it is helpful to understand how Aboriginal recipients of funding received from the Federal Government are actually organized and structured for the delivery of services to their members and for managing and reporting on disposition and results achieved with the funding received. This provides a clearer perspective on various aspects related to how funding is targeted; who actually uses this funding; and how local accountability works.

3.1.1 The First Nation as a "Reporting Entity"

An accounting perspective – a First Nation as a "Reporting Entity" (FNRE) – provides just such a disaggregated view of a First Nation in the diagram below.

FN as Reporting Entity (FNRE) Typical Functional Organizational Chart - Diagram

Description of figure: Diagram of the FN as Reporting Entity (FNRE) Typical Functional Organizational Chart

Source: Adapted from First Nation Audit Engagements, Part 1: Understanding the Reporting Entity. Bruce Hurst, CGA

This diagram is entitled "First Nation as a Reporting Entity (FNRE): Typical Functional Organizational Chart." It illustrates the Local Accountability and Reporting structure of First Nation Government and First Nation-controlled Entities and how they report back to First Nation Community Members.

At the top is the First Nation Constitution, which concerns First Nation Community Members. Both the Chief and Council as well as the Director of Operations are accountable to the First Nation Community Members.

The Director of Operations establishes FN-controlled Entities (both incorporated and unincorporated) to deliver services to the community, such as a School Board, Taxation Authority and Health Centre.

The Director of Operations is also responsible for the Capital Fund, Trust Fund and Operating Fund. The Operating Fund is used to enable Social Housing programs, Administration programs, Education programs, Social Development programs, Economic Development programs, Job Creation programs, and Capital programs.

The FNRE can take on many forms, but the most common structure is a First Nation government or Band as defined by the Indian Act.

Under the Indian Act, First Nations are constituted as communities, known as bands, and are governed by a chief and band council who are accountable to the members of the band. In recent years, certain First Nations have negotiated specific self-government agreements, which are implemented through federal and provincial or territorial government legislation. These agreements recognize the inherent right of self-government and remove those First Nations from the jurisdiction of the Indian Act.

As many studies repeatedly point out First Nations are not homogenous groups. They have different size populations, history, geography, culture, language, governance maturity, socio-economic conditions, treaty rights and circumstances, internal capacity, vision and priorities. Different bands have varying levels of resources, either own-source or federal funding, and they have different access to resources and training. Some now have a strong economy while others continue to rely to a much greater extent on traditional ways. First Nations also have different capabilities in terms of institutions and personnel to administer or deliver programs. Finally, because of factors such as size and geography, different bands incur different costs for providing the same services (e.g., as a result of diseconomies caused by higher prices to attract and retain good people and to secure third-party services as a result of local conditions and remoteness). As a result, specific accountability relationships will differ from First Nation to First Nation.

As apparent from the diagram above, a First Nation government is a multi-faceted organization. Not unlike a municipal government, it delivers a variety of services and programs to its membership. It also might establish other entities such as societies, trusts, taxation authorities, school boards, unincorporated enterprises, incorporated companies, limited partnerships, and joint ventures to carry out a particular function or role for the benefit of its membership.

3.1.2 Special types of entities

In certain instances Tribal Councils have been created. A Tribal Council is a First Nation entity established by a number of First Nations. It is usually governed by a board or council typically made up of a representative from each member First Nation. This is usually done to pool resources in order that the Tribal Council can provide advisory services and programs to its member First Nations. Tribal Councils might also provide non-financially driven services such as a political voice in negotiations on matters that affect the member First Nations.

In some cases, the member First Nations might not have sufficient funding resources to provide services in certain areas. If all member First Nations pool their resources, there can be enough funding to justify the provision of these services. For instance, any one member First Nation might not have enough funding to support an economic development officer, but if resources are pooled there will be sufficient resources to hire the officer and provide administrative support services for the benefit of all member First Nations.

In addition to funding provided by the member First Nations Tribal Councils often receive funding directly from funding agencies, including AANDC and other Federal Government departments.

Similar to Tribal Councils, First Nation Political Organizations have been established to provide a political/advocacy voice and similar services on behalf of First Nation people. A good example would be the Assembly of First Nations or Treaty Negotiation organizations in British Columbia.

3.2 AANDC Funding Arrangements

Transfer Payments have been the route which the department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) has taken to devolve over 85 percent of First Nation programming to First Nations administration, with a corresponding change in the fiscal relationship. In so doing, AANDC has also promoted the goal of self-government for those First Nations that wish to pursue it and the corresponding design of new funding models.

These payments are made through funding arrangements (also referred to as funding mechanisms or instruments). Funding arrangements are documents that spell out the terms and conditions under which transfer payments are made by AANDC for the delivery of programs and services. Recipients are subject to a specific set of rules called funding authorities, which reflect various financial and accountability conditions that Treasury Board imposes on funding departments.

The rules stipulate how programs and services will be funded, the responsibilities of federal and First Nation governments/organizations, how surpluses and deficits will be treated, and the steps to be taken should recipients incur significant debt or should they be unable to continue delivery of programs and services. The department uses a number of funding arrangements to transfer funds and to ensure accountability for the delivery of such programs and services and the judicious use of the funds transferred. The choice of funding arrangement is guided largely by the recipients' capacity to administer programs and services and the existence/non-existence of a self-government agreement with Canada.

| Table 1: Range of AANDC Funding Arrangements Going Forward (Pre-PTP) | |

|---|---|

| FUNDING ARRANGEMENT | DESCRIPTION |

| CONTRIBUTION AGREEMENT (CA) |

An arrangement AANDC enters into with eligible specific programs or projects which require significant interaction. Funding is based on reimbursement of eligible expenditures. Unexpended balances or unallowable expenditures are debts due the Crown. |

| COMPREHENSIVE FUNDING ARRANGEMENT (CFA) |

TheCFA is a program-budgeted funding arrangement thatDIANDenters into with Recipients for a one year duration and which contains programs funded by means of:

|

| CANADA/FIRST NATIONS FUNDING AGREEMENT (CFNFA) |

The CFNFA is a multi-year (five year) funding agreement that INAC and other federal government departments enter into with First Nations and First Nations organisations. CFNFAs have more flexible terms and conditions than CFAs, giving First Nations a greater range of options for delivering programs that meet their community priorities. They are typically for a duration of five (5) years. Funding is transferred in two streams: block and targeted, according to the following funding authorities: Block Funding:

|

| SELF-GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL TRANSFER AGREEMENT (SGFTA) |

The SGFA is a multi-year funding agreement that INAC and other federal government departments enter into with First Nations governments. These types of agreements are funded through grants, providing First Nations with the most flexibility in delivering programs to their communities. To be eligible, First Nations must first have entered into a Self-Government Agreement with Canada. The SGFTAs last for five (5) years, and is subject to renewal. |

Table 1 above provides a description of the pre-PTP funding arrangements, many still currently in use. Column one shows these arrangements AANDC in decreasing order of departmental control and increasing recipient flexibility. The choice of arrangement depends on the recipient's capacity to administer the programs and services and the funding received and to account for the use of the funds.

The department is currently reviewing a new architecture in establishing these funding agreements, shown in Table 2 below.

The funding regime is therefore complex and with the involvement of other departments beyond AANDC the programming obligations and reporting requirements can become tangled and onerous. A number of observers within and outside of AANDC, including the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Auditor General of Canada, the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grant and Contribution Programs as well as First Nations themselves, have called for a fundamental change in how departments understand, design, manage and account for their funding to First Nations.

| Table 2: Range of AANDC Funding Arrangements Going Forward (After PTP Implementation) | |

|---|---|

| FUNDING ARRANGEMENT | DESCRIPTION |

| New Funding Arrangement Model based largely on the CANADA/FIRST NATIONS FUNDING AGREEMENT (CFNFA) |

INAC has a funding agreement model. The model is based the principles of Agreement (CFNFA) approach which was co-developed byINACand Health Canada. The new agreement model permits:

|

| SELF-GOVERNMENT FINANCIAL TRANSFER AGREEMENT (SGFTA) |

The SGFA is a multi-year funding agreement that INAC and other federal government departments enter into with First Nations governments. These types of agreements are funded through grants, providing First Nations with the most flexibility in delivering programs to their communities. To be eligible, First Nations must first have entered into a Self-Government Agreement with Canada. The SGFTAs last for five (5) years, and is subject to renewal. |

3.3 Key areas of concern and opportunities for improvement

A number of reports from a variety of sources point to areas of concern and identify opportunities for improvement in the selection, architecture, management and accountability related to funding arrangements used by the department. Key ones and their conclusions are summarized briefly in the following paragraphs.

3.3.1 The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP)

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was appointed in 1991 to help, in the Commission's words, "…restore justice to the relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Canada and to propose practical solutions to stubborn problems." The Commission's final report was made public in November 1996.

The Commission proposed the following five objectives for financial arrangements that will support meaningful and effective self-government:

- Self-reliance - Aboriginal governments will need an adequate land base, adequate resources and the authority, such as tax powers, to have access to independent sources of revenue.

- Equity - New funding arrangements must produce equity 1) among Aboriginal governments; 2) between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples; and 3) between individuals.

- Efficiency - Financial arrangements and the processes employed to achieve them should be designed to be efficient.

- Accountability - Governments should be held accountable for their expenditures, primarily by their citizens and also by other governments from which they receive fiscal transfers.

- Harmonization - Arrangements should include mechanisms that provide for harmonization with adjacent governing bodies at the federal, provincial and municipal levels.

Based on these objectives, the Commission argued for fundamentally new fiscal arrangements, not adaptations or modifications of existing fiscal arrangements for Indian Act band governments. In fashioning these new arrangements, the RCAP recommends, "the negotiating parties should take into account the differences that exist between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal governments, such as the high cost of services in remote areas; the fact that many First Nations have non-contiguous land bases; the likelihood that many Aboriginal governments will not immediately exercise all of the jurisdiction available to them."

3.3.2 Various Auditor General Reports

The Auditor General of Canada established Aboriginal issues as an important focus area for performance audits. In its reports to Parliament between 2001 and spring 2010, the Office of the Auditor General published 16 chapters addressing First Nations and Inuit issues directly. Another 15 chapters dealt with issues of importance to Aboriginal people. The Office made numerous recommendations calling on Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (AANDC) and other federal departments to address a wide range of issues of importance to First Nations and Inuit people.

Most recently, in her 2011 June Status Report of the Auditor General of Canada, the Auditor General indicated that "many of the problems facing First Nations go deeper than the existing programs' lack of efficiency and effectiveness. We believe that structural impediments severely limit the delivery of public services to First Nations communities and hinder improvements in living conditions on reserves. We have identified four such impediments:

- Lack of clarity about service levels,

- Lack of a legislative base,

- Lack of an appropriate funding mechanism, and

- Lack of organizations to support local service delivery. "

3.3.3 The Blue Ribbon Panel Report

In June 2006, the President of the Treasury Board commissioned an independent panel to review and recommend ways of simplifying the administration of grants and contributions. On February, 2007, the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contributions released their much anticipated final report, From Red Tape to Clear Results. The report's conclusions cover a broad range of topics related to the administration of grants and contributions.

The panel identified a need for the federal government to dramatically simplify its reporting and accountability regime related to grant and contribution agreements. It recommended that the Treasury Board and departments modify their monitoring and recipient reporting requirements to avoid duplication or redundancy, and ensure that requirements are clearly connected to a demonstrable need.

Based on consultation with government, the voluntary sector, the business community and others, the panel set out the following three conclusions:

- There is a need for fundamental change in the way the federal government understands, designs, manages and accounts for its grant and contribution programs.

- Not only is it possible to simplify administration while strengthening accountability, it is absolutely necessary to do the first in order to ensure the latter.

- Making changes in an area of government as vast and multi-faceted as grants and contributions will require sustained leadership at the political and public service levels.

In their report, the Panel makes 32 short and long term recommendations to government that aim to change administrative practice. The recommendations fall into 4 categories:

- Respect the recipients—they are partners in a shared public purpose. Grant and contribution programs should be citizen-focused. The programs should be made accessible, understandable and useable.

- Dramatically simplify the reporting and accountability regime—it should reflect the circumstances and capacities of recipients and the real needs of the government and Parliament.

- Encourage innovation—the goal of grant and contribution programs is not to eliminate errors but to achieve results, and that requires a sensible regime of risk management and performance reporting.

- Organize information so that it serves recipients and program managers alike.

3.3.4 A Descriptive Model of Government of Canada - First Nations' Accountability

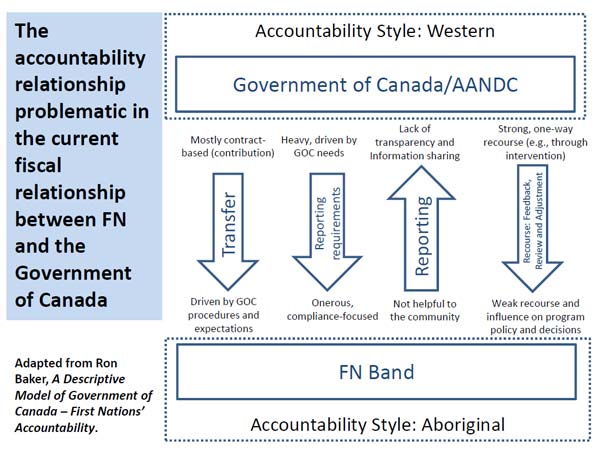

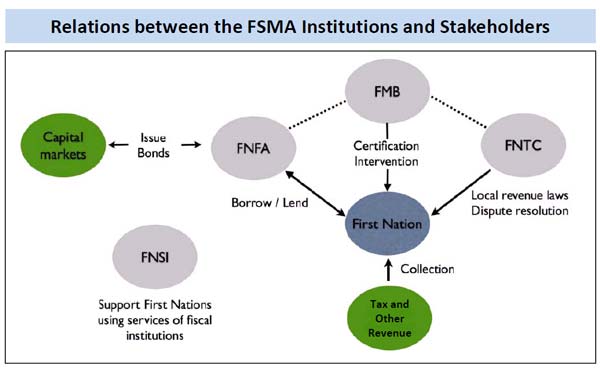

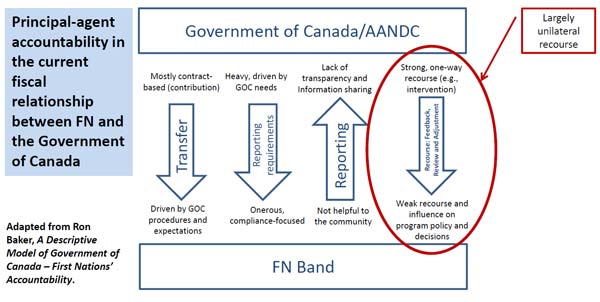

Baker (2010) has constructed a descriptive model (shown in the diagram) of the current accountability relationship between the Government of Canada and First Nations bands and the key problematic areas in this relationship.

He uses the model to examine each element in the Government of Canada-First Nations Band accountability relationship in order to:

- Assess the degree to which it is a partnership (i.e., government-to-government)[it is not];

- Look for contradictions amongst the elements of accountability that could lead to tensions [there are many, not the least being the differing accountability styles]; and

- Draw the attention of those currently working to rebuild or reconstitute the accountability relationship to the implications associated with each element.

This diagram is entitled "The accountability relationship problematic in the current fiscal relationship between FN and the Government of Canada." It shows the differing accountability styles of the Government of Canada and First Nations bands and highlights the problematic areas in their relationship.

The Government of Canada/AANDC has a Western accountability style; whereas, the FN Band has an Aboriginal accountability style. The main strains on their relationship are listed below:

- Transfers from the government to the band are mostly contract-based (contributions). They are driven by the government's procedures and expectations. The "Transfers" arrow points from the GoC/AANDC down to the FN Band.

- Reporting Requirements from the government to the band are heavy and driven by the government's needs. They are onerous and compliance-focused. Again, the "Reporting requirements" arrow points from the GoC/AANDC down to the FN Band.

- Reporting from the band to the government is not helpful to the community. There is a lack of transparency and information sharing. The "Reporting" arrow points up from the FN Band to the GoC/AANDC.

- Recourse (Feedback, Review and Adjustment) flows from the government to the band. There is a strong, one-way recourse (e.g. through intervention) on the government's side; however, the band is left with weak recourse and influence on program policy and decisions. The "Recourse, Feedback, Review and Adjustment" arrow points from the GoC/AANDC down to the FN Band.

The model begins with the transfer element. This is depicted as a unidirectional arrow from the Government of Canada (through a department) to a First Nations band. The prevailing transfers are contribution-based, driven by federal government conditionality, procedures and expectations. This is accompanied by the demand for information or "reporting requirements". This, too, is depicted by a unidirectional arrow reflecting the evidence that reporting requirements are dictated to the bands. The supply of information ("reporting") is unidirectional from the band to the Government of Canada. This connotes the one-sided nature of the accountability relationship. As Baker puts it, "To be more specific, it represents the relationship of accountability of the band to the Canadian government. In doing so it represents the view that historically the Government of Canada has not been accountable to First Nations, a significant factor". Finally the model shows the element of recourse (feedback, review and adjustment) as an exchange. Again this is a unidirectional exchange, reflecting the strong recourse available to the federal government (e.g., through intervention policy, discontinuance of funding, etc.), and the week recourse available to FNs.

3.3.5 Special Study on Departmental Funding Arrangements (2009)

The objective of the study was two-fold:

- To determine to what extent the funding arrangements available to the department in furtherance of its (and the government's) policy objectives respecting First Nations are appropriate for the purposes for which they are used, are effective in achieving the policy outcomes targeted, and are efficient both administratively (vertically) and as government (not just AANDC) policy instruments (horizontally); and

- To establish to what extent the accountability provisions in these arrangements are appropriate and effective in achieving the accountability and reporting needs of First Nation recipients (to local stakeholders) and those of the Minister (to Parliament and Canadians).

The special study found that, inter alia that:

- With the devolution of the delivery of programs and services from AANDC to First Nations and Tribal Councils, new funding arrangements and funding authorities were adopted that were intended to provide increased flexibility to First Nations to respond to their own needs. However, there has been little progress in terms of the movement of First Nations and Tribal Councils into block funding arrangements over the past ten years. There is a reluctance to move into more flexible arrangements or multi-year agreements because of concerns about annual adjustments, particularly for income assistance and primary and secondary education.

- Funding arrangements were seen to be focused on AANDC's policies and programs and not those of the recipient. Flexibility was constrained by the amount of funding.

- Despite the centrality of funding arrangements to the Department and their importance in terms of AANDC's relationship with First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Indian-administered organizations, we conclude that they are not appropriate. There is a lack of clarity about the overall objectives of the funding arrangements, a lack of coherence among programs and funding authorities that make up the arrangements, and no clear leadership at AANDC Headquarters. There is limited engagement of the recipients. The movement of First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Indian-administered recipients towards increasingly responsive, flexible, innovative and self-sustained policies, programs or services is not being promoted.

- In terms of the effectiveness of funding arrangements in meeting AANDC's policy and program objectives, there is very little information about what results are being achieved since most of the reporting relates to inputs, activities or outputs and very little about outcomes or results. Risk management, accountability and flexibility are not well balanced within the funding arrangements in terms of the amount of money involved, the nature of the program, or the capacity of the recipients.

- The amount of reporting was not commensurate with the amount of the funding, and there was some duplication across reports. Of more concern to the First Nation and Tribal Council recipients was the value of the reports to AANDC since they did not receive feedback.

- There is little coordination of funding arrangements across the federal government and widely varying terms and conditions across departments.

3.4 Departmental Action

Against this backdrop, the department is determined to address key shortcomings and take advantage of opportunities available – some of which were already identified in previous studies and reports, others which would become available through further review, analysis and consultation. This special study is just one among a number of concerted initiatives underway and planned.

3.5 Summary

A variety of previous studies and reports provide a rich tapestry of facts and narratives underlying the fiscal and accountability relationship between the federal government and FNs. The 2009 Special Study (IOG, 2009) provides an excellent summary of the significant kinks in this tapestry:

- General reluctance, particularly among AANDC program managers, to move into more flexible arrangements or multi-year agreements lest there is loss of control, diminished accountability and less information available to support Ministerial accountability, and because of concerns about annual adjustments, particularly for income assistance and primary and secondary education.

- Excessive focus on AANDC's policies and programs and not on those of the recipient.

- Movement of First Nations, Tribal Councils and other Indian-administered recipients toward increasingly responsive, flexible, innovative and self-sustained policies, programs or services is not being sufficiently promoted.

- Little information about what outcomes and results are being achieved on the ground, in the communities, since most of the reporting relates to compliance, inputs, activities or outputs and very little about outcomes or results.

- Reporting is burdensome, the utility of the information collected and the ways they are used are uncertain and not clearly commensurate with the degree of risk or the amount of funding involved.

- Insufficient coordination of funding arrangements across the federal government and widely varying terms and conditions across departments, making desirable aggregation difficult.

4. A Conceptual Framework for this Study

4.1 The Study Framework

The following paragraphs provide an outline of the fundamental assumptions behind this framework, its component elements and the key questions around which information collection, analysis and the presentation of findings have been structured.

4.2 Overall assumptions and key principles underlying the framework

The following are the "global" assumptions and key principles behind the conceptual study framework outlined in the diagram above:

- The department wishes to explore the increased use of grants in funding program services delivered by First Nations (FNs) to their members in the belief that this may be beneficial to both department and FN recipients and may represent a step toward delivering positive responses to long-standing recommendations in the RCAP Report, the Auditor General's various reports on funding to FN and calls by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and other Aboriginal organizations for deep change in the fiscal relationship between the Federal Government and FN.

- AANDC will favour the use of grants whenever appropriate and desirable, taking into account the differences that exist in the risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances characterizing FNs. "Appropriate" and "desirable" refer to those FNs whose risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances established through such instrumentalities as the General Assessment or certifications by agreed-upon third parties recommend and warrant the use of grants. It may be realistic to expect that only 10-15% of the over 600 FN currently funded through contributions may qualify, at least in the first "wave". A departmental strategy to bring new FN for consideration in subsequent waves (e.g., through capacity development work and "closing the gap" funding) will need to accompany this shift.

- The use of grants will not replace, but will continue to complement, the other types of funding agreements (e.g., contributions for project-based funding), whose use will continue as circumstances warrant.

- The Miawpukek Grant Agreement provides an appropriate departure point ("baseline") in the evolution to increased use of grants. As such, Miawpukek serves as a starting point on a journey toward a new Model Grant Agreement (MGA) that can be tailored to accommodate differences in the risk profiles, capacities and other circumstances characterizing FN. A description of the Miawpukek Grant Agreement and a rationale for its use as a baseline/ departure point is provided in Annex B.

- The new Model Grant Agreement should provide a fiscal transfer vehicle for both a single department and multiple departments as funders, based on the principle of "one community, one agreement" whenever that is possible and desirable from both a funders' and FN's perspective.

- To ensure streamlined administration, where multiple funders are involved, the MGA should be administered through a "single window", with AANDC acting as the point department and coordinator.

- Finally, the MGA should establish an accountability relationship between funders and FN that provides more balance and symmetry through an increased "two-way" flow between funders and FN. As such, a desirable end-state would be to establish a "reciprocal" or "mutual" accountability relationship, with flows in both directions.

4.3 The four thematic quadrants of the framework

As indicated in the assumptions and principles articulated above, the Miawpukek Grant Agreement (MGA) is a starting point. It would be unreasonable to assume that the agreement in its pristine form will be able to accommodate the entire range of risk profiles, capacities and circumstances extant in the FN funded by the Federal Government. As such, a number of additional provisions, approaches and practices will be required for the MGA to have the range and requisite variety to make it relevant and usable along the entire continuum of "grant-grade" FN risk profiles, capacities and circumstances.

The search for, analysis and presentation of these additional provisions is organized into four categories; these categories are actually the four thematic quadrantsshown in the Conceptual Study Framework diagram. They are:- Accountability relationship (recasting the accountability relationship between the federal government and FNs);

- Flexibility and Equity (providing added recipient flexibility when appropriate while ensuring that adequate funding flows to those areas that need it most through, for instance, "equalization", "capacity-building, "closing the gaps" and other targeting approaches);

- Performance and Reporting(shifting and strengthening the focus of reporting to performance-based reporting while reducing the administrative and reporting burden in accordance with recipient capacity and risk involved); and

- Eligibility and Conditionality (ensuring, through rigorous up-front assessments, that adequate eligibility provisions and ongoing controls and assurance are in place, commensurate with recipient capabilities, capacity and risk, to manage the funding agreement with appropriate probity, openness and transparency).

The paragraphs below discuss briefly these quadrants. The same headings are then used to present the findings and conclusions of the report, which will form the object of the following sections.

4.3.1 Accountability relationship

The object of this quadrant is the articulation of accountability relationship models that should inform provisions and practices that could be included in the new MGA in addition to those already available in the Miawpukek Grant Agreement.

Thus the key question here is: what practices, techniques, instruments and approaches could be considered to help create a healthy accountability relationship and enhance accountability (from FNs to members, from FNs to Federal Government, from Federal Government to FNs)? Answers will emerge through an analysis of relevant AANDC/HC, Canadian and international practices and approaches.

4.3.2 Flexibility and Equity

This quadrant provides the focus for the identification of practices, techniques, instruments and approaches that could also be considered to help increase flexibility to FNs in the use of funding and to advance "equalization," "increased capacity" and "closing the gaps" outcomes in the application of the funding. Principal sources of information for this quadrant are:

- Federal to Provincial and Territorial and Provincial to Municipal Transfers;

- Provincial-local Transfers, with particular emphasis on transfers from Provinces to municipalities; and

- Transfers to Self-Governing FNs with which Canada has established a Self-Government Funding Agreement (SGFA).

4.3.3 Performance and Reporting

This quadrant seeks the identification of practices, techniques, instruments and approaches that could also be considered to help increase reporting focus on program results and outcomes while reducing administrative and reporting burden on both FNs and the department.

Sources of information in this process include:

- Interviews;

- A review of AANDC's Multi-Year Community Fiscal Transfer Program;

- A review on the various "Smart Reporting" initiatives;

- A review of work undertaken by Federal Government small departments and agencies to lighten the reporting burden placed on them by Central Agencies;

- A review of the MAF reporting process for small departments and agencies;

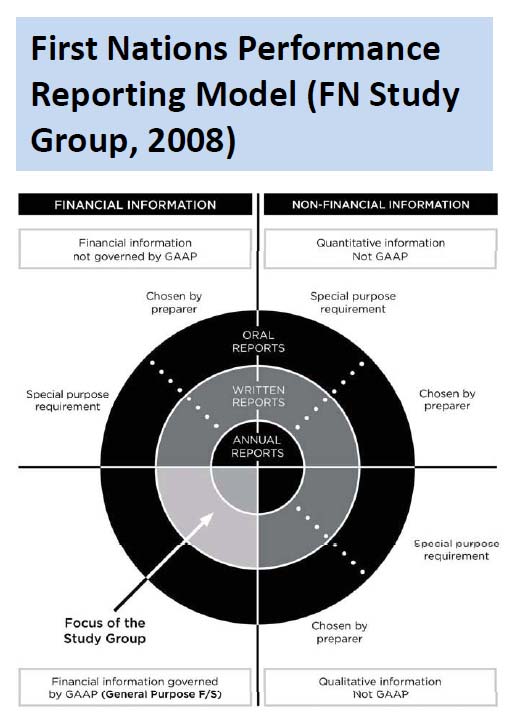

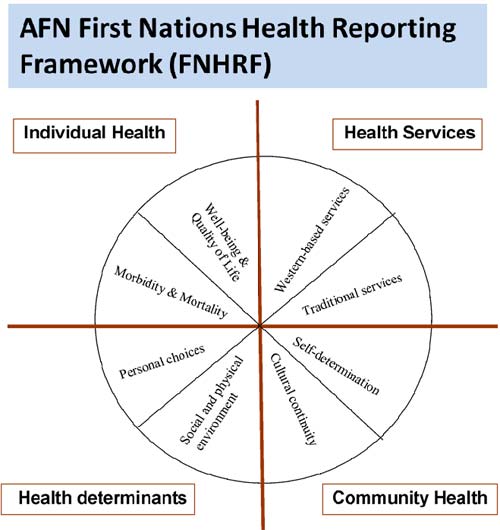

- Work on the First Nations Health Reporting Framework; and

- A review of international practices related to reducing administrative and reporting burden.

4.3.4 Eligibility and Conditionality

This quadrant seeks to identify what provisions could be considered in the eligibility and conditional aspects of the MGA in order to provide the necessary and adequate front-end assurance of qualifications, performance and funds management in light of the risk profile, capacity and circumstance differences among FNs. Relevant provisions from existing departmental Grant, AFA, FTP, and Contribution Agreements will be a primary source.

It should be noted that this quadrant will only be indirectly (or tangentially) addressed in this study as it forms the object of another study (Orbis) which reported separately.

4.4 Summary

This section proposes a conceptual framework for this study to help identify relevant and appropriate complements to the Miawpukek Grant Agreement. These complements, in the way of provisions, approaches and practices, should ensure that he MGA has the range and requisite variety to make it relevant and usable along the entire continuum of FNs risk profiles, capacities and circumstances. The four thematic quadrants of this framework are:

- Accountability relationship;

- Flexibility and Equity;

- Performance and Reporting; and

- Eligibility and Conditionality.

5. Accountability relationship

5.1 Definitions

In the definition of accountability provided by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG December 2002 Report, Chapter 9), accountability is a relationship based on obligations to demonstrate, review, and take responsibility for performance, both the results achieved in light of agreed expectations and the means used. The Auditor General's definition of accountability is linked with an accountability framework that consists of five elements:

- Clear roles and responsibilities. Roles and responsibilities should be well understood and agreed on by the parties.

- Clear performance expectations. The objectives, the expected accomplishments, and the constraints, such as resources, should be explicit, understood, and agreed on.

- Balanced expectations and capacities. Performance expectations should be linked to and balanced with each party's capacity to deliver.

- Credible reporting. Credible and timely information should be reported to demonstrate what has been achieved, whether the means used were appropriate, and what has been learned.

- Reasonable review and adjustment. Fair and informed review and feedback on performance should be carried out by the parties, achievements and difficulties recognized, appropriate corrective action taken, and appropriate consequences carried out.

In relation to the first element, the Report of The Financial Reporting by First Nations Study Group, (CICA, 2008) notes that the "there needs to be a clear understanding of the duties, obligations and related authorities of each party. Accountability is a two-way street and all parties to the accountability relationship have roles and responsibilities. As accountability relationships are not static, these roles and responsibilities will adapt to suit changes in social, economic and political circumstances."

5.2 Salient characteristics

As CICA (2008) notes, "First Nations are regaining and extending governance authority. The devolution of program management to First Nations governments, greater band control of government funding and an increase in the number of First Nations negotiating self-government agreements have changed the accountability relationships of First Nations. Most important, there has been a change in the relationship between the leadership of First Nations and their members. To have robust governance, not only is it necessary for the leadership of a First Nation to be accountable to its members, the members of a First Nation must also take responsibility for staying informed and holding their leadership accountable. As a result, the primary accountability relationship of a First Nation government is with its members."

The CICA report also points out that the relationship between First Nations and the rest of Canada is also changing. "Now, in most instances, First Nations – whether self-governing or operating under the Indian Act – will continue to depend on federal government transfers for funding for province-like programs and services such as health and education for on-reserve members. Because these are similar to the programs and services that the provinces and territories deliver to other people throughout Canada, the ongoing dependence of First Nations will be no different than the ongoing dependence that provinces and territories have on federal government transfers."

Writing on the relationship between First Nations and the rest of Canada, the Auditor General also notes in her 2006 Update (OAG, 2006) that "the relationship is still evolving, with continued emphasis on the transfer of program administration to First Nations and self-government initiatives."

5.3 FN Accountability Relationships

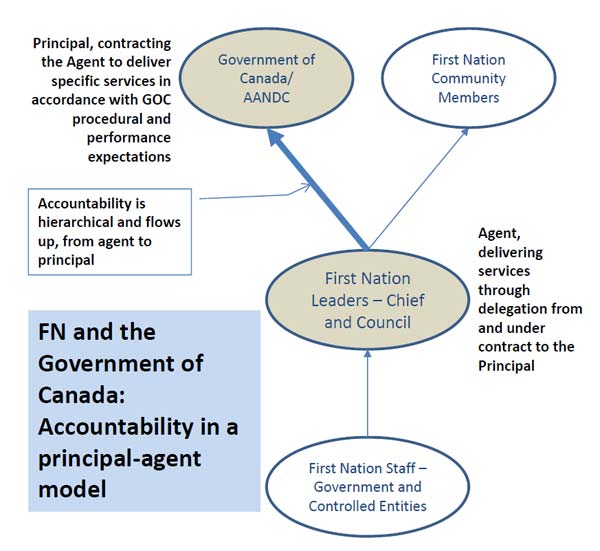

Attached is a diagrammatic view of the main accountability relationships a First Nation typically maintains.

Adapted from Ron Baker, A Descriptive Model of Government of Canada - First Nations' Accountability. In turn, adapted from John Graham, Policy Brief No. 4 - Building Trust: Capturing the premise of accounting in an Aboriginal context. Institute on Governance, 1999.

This diagram is entitled "First Nation Accountability." It is a relational map of different groups to which they are accountable. At the centre is the "First Nation Leaders – Chief and Council," who (hierarchically or vertically speaking) are accountable to the "First Nation Community Members" and the "First Nation Staff – Government Controlled Entities." The "First Nation Leaders – Chief and Council" (horizontally or laterally speaking) are accountable to "Federal and Other Levels of Government (Provincial/Territorial)" as well as "Capital providers."

As apparent, First Nations have three key main accountability relationships:

- To First Nation members living on-reserve and off-reserve, who have a right to select their First Nation government leaders. Thus the primary accountability relationship is the relationship between a First Nation government and its members. In addition, there are accountability lines within First Nations governments: (1) elected and appointed representatives and officers; (2) operational and administrative management; and (3) employees.

Both FN government and members have important roles to play in the accountability relationship. The members have a duty to engage: they select their government and are also responsible for any changes in that government. Therefore, they need to hold their government accountable by reviewing government performance and ensuring that their government will make any required adjustments to its performance. Otherwise, there will be no accountability and the government will have no legitimacy. The First Nation government has a responsibility to provide services and ensure the well-being of its members. The chosen government needs to make sure that the members of the First Nation understand the activities their government has undertaken and that they have an opportunity for meaningful input. - To other governments that provide funding to First Nations, including federal, provincial and territorial governments that have established legal or economic relationships with First Nations. Similarly, in the relationship between the federal government and the First Nation there is a need for the parties to understand their roles and responsibilities. Here, the emphasis is on federal funding and use of that funding by the First Nation for the purposes intended.

- To capital providers who are investors, lenders and creditors and use the information for decision-making purposes. In the relationship between a First Nation and capital providers, the roles and responsibilities are more narrowly defined. Capital providers will assess the credit-worthiness of the First Nation and provide capital accordingly. The First Nation will be required to repay the principal amount as well as interest on the principal.

It should be noted in the FN Accountability diagram above that the FN accountability relationships can take two "orientations": hierarchical (vertical) and lateral (horizontal). "Orientation" typically refers to the nature of power in the relationship. As one commentator suggests (Baker, 2010) "the orientation of the relationship will be defined by the balance of power. Where power between the two parties is asymmetrical within the relationship, the orientation is hierarchical and assumes the form of a principal-agent arrangement. Where power is shared, the relationship can be said to have a lateral orientation or a joint undertaking between equal partners."

Baker goes on to point out that "power emanates from the ownership of resources, responsibility or both. In a principal-agent arrangement the owner of resources or the owner of responsibility (meaning one who is ultimately accountable for the discharge of those responsibilities) transfers resources or delegates responsibility to the agent. The relationship can be viewed as a contract where one party transfers resources and/or responsibilities to another and in return expects an account of how those resources were used or those responsibilities discharged."

The remaining paragraphs in the discussion on accountability will focus on the first element: the nature of the relationship viewed through the lens of roles and responsibilities in the accountability relationship. The remaining three elements of the accountability relationship – expected performance; reporting requirements; and mechanisms for review and adjustment are addressed in the section dedicated to the third quadrant – Performance and Reporting – downstream.

5.4 Current FN accountability relationship to the Federal Government: mostly a principal-agent relationship

In 1996, the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) conducted a study and produced a report entitled "Accountability Practices from the Perspectives of First Nations" (OAG, 2006). The objectives of this study were to explore the accountability relationship with the government based on actual views of selected First Nations collected through focus sessions and interviews.The report indicated that the government and First Nations generally "no longer understood each other's needs", making the current construct of accountability "unworkable because little legitimacy is attached to it".

One of the key conclusions was that most First Nation participants in leadership positions or band council offices saw themselves as responsible to their membership for results and to the federal government for process. While participants recognized the need for the government to implement some systems and procedures to facilitate programs delivery, a less onerous process and more of a focus on results was stressed. One study on accountability in the aboriginal context notes that "since the mid-1980s, the federal government and in particular the Auditor General has become increasingly cognizant of the disparity between what might be meaningful accountability processes for First Nations and what the government presently expects" (Cosco, 2005, p. 153).