Archived - Formative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: April 2011

Project No. 10005

PDF Version (271 Kb, 46 Pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response/Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Executive Summary

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) undertook a formative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan. Announced by the federal government in 2007, the Action Plan set in motion fundamental reforms to the specific claims process intended to bring increased fairness and transparency.

The purpose of the evaluation was to obtain an independent and neutral perspective on how well the Action Plan is achieving its expected results; the extent to which the design and delivery of the Action Plan is supporting the achievement of the departmental objectives with respect to the resolution of specific claims; as well as to identify opportunities to improve the Action Plan's design and implementation.

The methodology used to conduct this evaluation included a document review; a literature review; a file review, as well as interviews with a wide range of key informants including federal and provincial governments and First Nation representatives. The evaluation was conducted by PRA Inc. under the direction of the EPMRB and with the support of an advisory committee comprising of representatives from the Specific Claims Branch and the Department of Justice Canada.

Key findings and conclusions from the evaluation are as follows:

Rationale and relevance

The objectives of the Specific Claims Action Plan strongly align with government priorities and the roles and responsibilities of the federal government toward First Nations. Treaties between First Nations and the Crown are of the utmost value in ensuring a strong and collaborative relationship between the federal government and First Nations. Fulfilling obligations to provide land and other assets under these treaties, and other outstanding lawful obligations owed to First Nations, deserve to be addressed without undue delay. The Action Plan aims to address the shortcomings that have become evident in the implementation of Canada's specific claims process.

The Action Plan addresses longstanding concerns from First Nations. First and foremost, the Action Plan has allowed for the establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal, a fully independent institution that has the legislative authority to make final decision on claims. This Tribunal addresses the concern systematically expressed by First Nations that Canada was both a party and a judge when it came to dealing with specific claims outside of the court system. The Action Plan also responds to the needs of First Nations to have a more expedient process, within INAC and the Department of Justice Canada, to process specific claims. Moreover, the dedicated fund also sends a strong message respecting the commitment of the federal government to set aside sufficient financial resources to deal with any new settlements.

That said, the implementation of the Action Plan is also having a less desirable impact on the relationship between the federal government and First Nations. The design of the minimum standard process as well as changes made to the review and negotiations have further excluded First Nations from the specific claims process. The three-year operational model for negotiation appears particularly problematic. There appears to be an increasing sense of frustration among First Nations that the very spirit of the Action Plan may not be upheld if this operational model is systematically imposed, regardless of the nature and complexity of each claim.

Mediation services will be used during the negotiation of specific claims for the purpose of overcoming impasses. A Mediation Services Unit has been established within the department. Although the unit is not yet fully operational, work has been initiated to create the mechanism by which independent mediation services will be accessed. Mediation remains highly valued by First Nations.

Design and delivery

The Specific Claims Branch has developed and implemented new internal procedures relating to key components of the specific claims process. These new procedures are significantly redefining the role of INAC, the Department of Justice Canada, and First Nations. The full extent of the impact has yet to unfold, as the Specific Claims Tribunal is not yet operational.

INAC is using a minimum standard to review new claims tabled by First Nations. Evidence from this evaluation indicates that the review of new claims against this minimum standard occur in a timely fashion. Where the process could be improved is in providing detailed feedback to any First Nation whose claim is found not to meet this minimum standard. There appears to be very little feedback currently provided which makes it challenging for a First Nation to determine the proper course of action to follow.

The Specific Claims Branch is currently attempting to review all new claims and inform First Nations whether an offer to negotiate will be made within the three-year period outlined in the Specific Claims Tribunal Act. In doing so, the Branch has had to deal with a significant backlog. It is unclear whether this three-year goal will be achieved. A large number of claims have been reviewed to date but it is unclear whether any portion of the backlog will remain come October 16, 2011.

While no set deadlines exist to negotiate a claim, the Specific Claims Tribunal Act stipulates that First Nations may take a claim to the Tribunal after three years if a settlement of the claim has not been achieved. As a result, the Specific Claims Branch has implemented a three-year operational model to negotiate and settle claims. As noted earlier, this approach is problematic. First, it is evident that the Branch will be unable to meet this goal for a number of claims which are simply too complex. Second, while this model may assist the Branch in planning human resources, it hardly reflects the spirit of the Action Plan, particularly when it leads to a substantial number of files closed possibly due to a deadlock in negotiation that may be prevented by extending the timeframe for negotiation.

The new internal procedures are putting significant pressures on the staff of the Specific Claims Branch. The Branch has not been able to fill all positions expected as a result of the Action Plan. This has proven particularly challenging in light of the large backlog of files that the Branch had to deal with.

At this point, the evaluation indicates that First Nations face challenges, particularly as it relates to the preparation of the initial claim submission. Since the minimum standard must be achieved and the claim submission may need to be strong enough to be tabled to the Tribunal, First Nations must invest a greater level of resources in developing these claims.

The Specific Claims Branch has developed a solid database that provides up-to-date information on the status and progress of each claim filed with the Department. In addition, the Negotiations Directorate has developed a tool, based on Microsoft Project, which serves to forecast and monitor the various steps included in the negotiation process. Research and Policy Directorate also has developed and implemented a Microsoft Project tool that tracks the status and progress of claims under assessment. These are exemplary practices that should be maintained.

Efficiency and economy

In the current context, the Action Plan represents the most appropriate and efficient process to achieve the Action Plan's expected results. At the time the federal government unveiled the Action Plan, the specific claims process needed to be improved. As stated earlier, the four pillars included in the Action Plan appear to be appropriate to address what were seen as the shortcomings of the process.

Significant financial resources have been assigned to the Action Plan and, to date, this level of financial resources appears sufficient to support effective implementation of the Action Plan. As for human resources, it has already been noted that the Specific Claims Branch has not been able to fill all positions that were initially expected which is putting considerable pressures on the current staff.

The dedicated fund is sending a clear message that the federal government is setting aside substantial resources to settle specific claims. Only time will tell if the $2.5 billion over 10 years will be sufficient to settle all valid claims. It should be noted that, should additional funds be required, there are alternative processes that may be followed to secure these resources.

Successes and early outcomes

The progress made to date in implementing the Action Plan is contributing to most of the planned results in the first three to five years.

The passing of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act provides First Nations with a set timeframe that allows them to forecast and monitor the progression of their claims. Moreover, and as documented throughout this report, this new timeframe has undoubtedly accelerated the processing of specific claims. While not operational yet, the establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal is also ensuring that First Nations and the federal government can access an alternative to litigation that brings the expected finality to the claims process.

The establishment of the dedicated fund is facilitating, to a certain extent, the pay out of settlements. There is still, however, a fairly lengthy process that the Specific Claims Branch needs to complete in order to issue the required settlement. This has had a direct impact on the timeframe needed to complete the negotiation process. The dedicated fund, combined with the reporting process that the Specific Claims Branch has established, has increased transparency in relation to the financial resources invested by the federal government to settle valid claims.

The new revised internal procedures are expediting the claim process and some efforts have been made to tailor the process to the nature of the claims, for instance through expedited legal opinions. As noted earlier, whether these new procedures will completely eliminate existing backlogs is uncertain, but there is no doubt that a large portion of existing backlogs will have been dealt with.

Prior to the Action Plan, mediation services were available to negotiation tables upon request. Mediation services continue to be available upon request. Mechanisms, such as a Standing Offer and roster of independent mediators, are being developed to facilitate and accelerate access to independent mediation services.

There is little doubt that the changes resulting from the Action Plan could be expected to enhance the ability of the federal government and First Nations to settle specific claims, which in turn could promote greater social and economic development. Whether a greater trust between First Nations and the federal government will emerge from this renewed process has yet to be seen. This report identifies areas of improvement in the specific claims process that could support the achievement of this fundamental goal.

Recommendations

It is recommended that INAC:

- Consider modifying the current operational model for negotiation and settlement, in order to extent the expected period of negotiation beyond three years if required.

- Review the procedures relating to the initial review of claims against the minimum standard to ensure that appropriate feedback is provided to any First Nation whose claim has been deemed not to meet the minimum standard.

- Communicate to all stakeholders on how activities under the mediation services pillar will be used and what process will be followed to offer these services. This process should be developed with First Nations.

- Communicate more effectively with all stakeholders the process for claims over $150 million.

Management Response / Action Plan

Formative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan

Project: 10005

Sector: Treaties and Aboriginal Government

Management Response

The Specific Claims Action Plan was announced by the Prime Minister in June 2007. Much progress has been made to implement the Action Plan, which is confirmed by the Formative Evaluation findings. The findings were largely anticipated by Specific Claims Branch. The findings identify achievements to date and areas where more work needs to be done. While the Specific Claims Branch will examine the concerns identified in the findings closely, it will do so taking into account the reality of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, and government commitments related to the quick and fair resolution of specific claims.

The findings of the Formative Evaluation will be used to inform: the 5-year review of Justice at Last in 2012-13; the Audit of Specific Claims in 2012-13; the Summative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan, planned to take place in 2012-13; and the legislative review of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, planned for 2013-14. The findings will also be taken into consideration in the context of SCB work planning. The findings may also be highlighted in various documents, such as the Specific Claims progress report, which is updated on a bi-annual basis and is posted on INAC web-site, briefing notes to senior officials, and briefing material prepared for Standing Committee appearances by INAC officials.

Response to Recommendation 1: One of the fundamental goals of the Specific Claim Action Plan was to ensure faster processing and accelerated settlement of specific claims. The three-year operational framework was primarily designed to support this goal. As such resources were calculated on this basis and as a cost effective measure. More importantly, extending the negotiation (or assessment) time periods would make the Crown vulnerable to references of claims by First Nations to the Tribunal and related criticisms, such as allegations of an intentional transfer of the "burden" to the Tribunal.

Response to Recommendation 2: First Nations are advised, in writing, of the specifics of the deficiencies in their claim submission. These letters customarily contain substantial explanations about why the submission did not meet the Minimum Standard. These standards were developed in consultation with the AFN and have been available to First Nations on the INAC website. It is noted that SCB research staff work with First Nations to correct deficiencies in submissions, albeit not as extensively as prior to the SCTA. We must be cautious not to guide First Nations in the development of their claim but find a balance in the level of feedback provided to them.

Response to Recommendation 3: INAC will facilitate access to mediation services through the administration of a roster of mediators available through a Standing Offer. Mediators will be chosen by the table with the consent of the parties. The AFN, representing the interests of First Nations, has been invited, and has been funded, to participate in the development of selection criteria for mediators and other aspects of the selection process. The AFN has also been invited, and received funding to participate in the development of media-related communications and education tools. To date, the AFN has declined these invitations. It is noted that mediation services were available to negotiation tables before the Action Plan and remain available upon request. Mechanisms, such as a Standing Offer and roster of independent mediators, are being developed to facilitate and accelerate access to independent services.

Response to Recommendation 4: It is noted that there are very few known large value claims. As was stipulated in the Action Plan, these large value claims require to be considered by Cabinet for acceptance and therefore subject to the Cabinet process which is confidential. Efforts will be made to ensure that information on the INAC website is updated to reflect this.

Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Consider modifying the current operational model for negotiation and settlement, in order to extend the expected period of negotiation beyond three-years if required. | We do not concur. | Director General, Specific Claims Branch, TAG | Start Date: completed |

|

Recommendation considered. No action will be taken as a three-year operational model was adopted by SCB in response to the primary objective of the Action Plan - to accelerate the resolution of specific claims. Notwithstanding this, it is expected that some First Nations will opt to continue negotiating past the three-year point, when claims are especially complex and the parties agree that a negotiated settlement is a near-term likelihood. |

Completion Date: completed |

||

| 2. Review the procedures relating to the initial review of claims against the minimum standard to ensure that appropriate feedback is provided to any First Nation whose claim has been deemed not to meet the minimum standard. | We do concur. | Director General, Specific Claims Branch, TAG | Start Date: May 2011 |

| The responsibility for the development of a specific claim rests with the First Nations. There needs to be a balance in the level of feedback provided to FNs. SCB will further review the type and level of feedback provided to the First Nations to ensure that First Nations receive meaningful feedback when a claim submission is deemed not to have met the Minimum Standard and is not filed with the Minister. | Completion Date: June 2011 |

||

| 3. Communicate to all stakeholders on how activities under the mediation services pillar will be used and what process will be followed to offer these services. This process should be developed with First Nations. | We do concur. | Director General, Specific Claims Branch, TAG | Start Date: June 2011 |

| The process for mediation was discussed with the Assembly of First Nations and they were also invited to participate at various stages of the process. Once the standing offer is in place and the roster of mediators has been established, INAC will publish on its website the steps for accessing mediation services. As well, hard-copy information packages will be developed. | Completion Date: December 2011 |

||

| 4. Communicate more effectively with all stakeholders the process for claims over $150 million. | We do concur. | Director General, Specific Claims Branch, TAG | Start Date: June 2011 |

| INAC will provide further clarification by publishing information on the INAC website that clarifies the process for claims over $150 million. | Completion Date: December 2011 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on April 15, 2011 by:

Judith Moe

A/ Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on April 15, 2011 by:

Patrick Borbey

Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Treaties and Aboriginal Government

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Formative Evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 19, 2011.

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) undertook a formative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan. The purpose of the evaluation was to obtain an independent and neutral perspective on how well the Action Plan is achieving its expected results; the extent to which the design and delivery of the Action Plan is supporting the achievement of the departmental objectives with respect to the resolution of specific claims; as well as to identify opportunities to improve the Action Plan's design and implementation. EPMRB contracted the services of PRA Inc. to provide assistance during all stages of the evaluation process.

This report is divided into five sections. This introduction provides an overview of the evaluation process, along with a description of the Specific Claims Action Plan. Section 2 describes the methodology associated with the study. It includes a description of the scope and timing of the evaluation, a summary of evaluation issues and questions addressed in this report, along with a description of the various methods used to collect evaluation data and findings. Section 2 also provides an overview of the roles, responsibilities, and quality assurance used to support this study. Sections 3 and 4 summarize all findings that have emerged during the data collection process. Section 3 specifically explores the relevance of the Action Plan, while Section 4 focuses on the actual performance of the four pillars included in the Action Plan. Finally, Section 5 provides conclusions and recommendations as applicable.

1.2 Description of the Action Plan

1.2.1 Background

Specific claims are claims made by a First Nation against the federal government which relate to the administration of land and other First Nation assets or to the fulfillment of Indian treaties. The nature of grievances qualifying as specific claims can vary widely, reflecting the diverse historical relationships between different First Nations and the Crown. Examples include failure to provide enough reserve land, the improper management of First Nation funds, or the surrender of reserve lands without the lawful consent of a First Nation.

A comprehensive process for the negotiation of specific claims was first introduced in 1973. This alternative dispute resolution process was intended to provide an alternative to litigation through a more timely, cost-effective, and co-operative negotiation-based process that would lead to desirable outcomes for both parties.

The specific claims process was criticized by First Nations and other parties. In 2006, the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples voiced criticisms in Negotiation or Confrontation: It's Canada's Choice (2006). Canada responded to this Senate report with Justice At Last: Specific Claims Action Plan (2007). This Action Plan, announced on June 12, 2007, set in motion fundamental reforms to the specific claims process intended to bring increased fairness and transparency.

1.2.2 The Action Plan's fourpillars

The Action Plan is based on four pillars:

- Establish an independent tribunal with the power to make binding decisions;

- Designate a fund in the amount of $250 million per year, for 10 years, for settlements and to pay tribunal awards;

- Streamline internal government procedures to reduce or eliminate the backlog of unprocessed claims; and

- Improve access to mediation services to support negotiations.

Pillar 1: The Specific Claims Tribunal Act

The Specific Claims Tribunal Act came into effect on October 16, 2008. The Act legislates the establishment of an independent Tribunal capable of making binding decisions about the validity of specific claims and awarding monetary compensation for them to a maximum value of $150 million per claim. It alsosets out rules and guidelines regarding the Tribunal's organization, operation, and use.

The Act determines that the Tribunal should be staffed with no more than six full-time members appointed from a roster of six to eighteen Superior Court judges. The Actalso specifies four conditions under which First Nations may file a claim with the Tribunal. First Nations may access the Tribunal:

- If, after research and assessment, the Minister decides not to negotiate the claim, in whole or in part.

- If the Minister fails to notify the First Nation within three years of a claim having been filed with the Minister about whether the claim is accepted for negotiations.

- If a claim being negotiated has not been resolved by a final settlement agreement within three years of the date on which the Minister notified the First Nation of the decision to negotiate the claim.

- If the Minister consents to allow the First Nation to file the claim with the Tribunal before three years of negotiations have passed. [Note 1]

In outlining these conditions, the Act sets timelines for the assessment and negotiation of claims. It allows the government three years to conduct the research and assessment stage, and to provide a response to the First Nation on whether the claim has been accepted or not for negotiations. It also allows three years for the parties to attempt to reach settlement before granting the First Nation access to the Tribunal without approval from the Minister. [Note 2]

Other notable aspects of the Act include the following:

- The Actspecifies that statutes of limitations or the doctrine of laches do not apply to specific claims heard by the Tribunal.

- It requires that claims be assessed (in terms of content, form, and manner of presentation) against a reasonable minimum standard, the satisfaction of which determines whether a claim can be filed with the Minister.

- The Act places an upper limit of $150 million per claim on the value of claims that can be awarded compensation through the Tribunal.

- While the Actgives the Tribunal authority to award compensation against the Federal Crown, it limits the form of compensation that the Tribunal can award and the circumstances under which compensation can be awarded (i.e., the Tribunal can only award monetary compensation and it cannot award compensation for punitive or exemplary damages).

By granting First Nations access to Tribunal hearings and registry services, these activities are expected to provide First Nations with a timelier alternative to litigation in the event that negotiations are not successful or that a claim is not accepted for negotiations. The Tribunal's independent nature is expected to address First Nations' long-standing concerns about the perceived conflict of interest in the claims process, to contribute to trust-building between First Nations and the Crown, and to increase perceptions of legitimacy regarding the specific claims process. The Tribunal's authority to issue final, binding decisions and to award compensation against the Federal Crown will bring finality and closure to the process.

The timelines established are intended to accelerate the claims process in order to bring faster resolution of more claims. The timelines are also intended to give First Nations a better indication of the expected evolution of their claim.

Pillar 2: dedicated fund

The Action Plan includes plans for the establishment of a dedicated fund of $250 million per year for ten years (for a total of $2.5 billion) committed to the resolution of specific claims. This represents an increase in the amount of resources devoted to specific claims settlement prior to the Action Plan. Authorized payments from the fund are triggered by specific claims settlements or by Tribunal decisions.

The fund is expected to increase capacity to pay out settlements and to allow easier access to funding for those involved in negotiating specific claims and in making settlement offers.

The fund is also expected to promote transparency and public awareness by publically committing the source of funds for the resolution of specific claims. New reporting requirements related to the use of the fund are expected to further enhance the transparency of the specific claims process. By providing First Nations with assurance that adequate funds will be available to settle their claims in any given year, the fund is expected to promote trust between First Nations and the government, and to promote greater certainty in the process.

Pillar 3: mediation services

Prior to the Action Plan, mediation services were provided by the Indian Specific Claims Commission. Since the Action Plan, the Commission has been dissolved and a roster of independent mediators is being established to provide mediation services. Mediators are to be called on to aid negotiations when needed. Both parties (i.e., First Nations and the Crown) are to agree on using such services and agree on the individual mediators selected to mediate each case.

The parties' ability to access mediation services during negotiations is expected to result in a more co-operative negotiation process. In particular, the independent status of mediators can help parties to explore contentious issues from alternative perspectives. The federal government has decided that having a roster of mediators to provide these services, who are only called upon when they are needed, is a cost-effective alternative to creating a separate entity to provide mediation services. By helping parties to overcome impasses in negotiations, access to mediation services is intended to result in more claims being settled more efficiently through negotiation, rather than through the Tribunal or litigation.

Pillar 4: internal government procedures

To meet the Action Plan's goals of addressing the specific claims backlog and processing delays, and to meet the timelines set out by the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, INAC proceeded with a streamlining of internal government procedures.

As mentioned, one change to internal government procedures is the addition of the minimum standard assessment to the early review process. In implementing this standard, claims not able to meet the standard are immediately returned to the First Nation and are only filed with the Minister once the standard is met. Other changes to internal procedures include bundling similar claims during the research and assessment stage and separating small-value claims from larger, more complex claims. Efforts are made by members of the Department of Justice to produce expedited legal opinions on small-value claims, and by members of the Specific Claims Branch to speed up the settlement process.

All changes to internal procedures are intended to improve the efficiency of the specific claims process, enabling compliance with the expected timelines, and clearing the backlog of specific claims. The minimum standard is intended to provide First Nations with clear guidelines to aid with the preparation of their claims, thus improving the quality of claims submissions and reducing the time needed for research and historical and legal assessments. Similarly, organizing claims according to size and complexity (and removing large, complex claims valued at over $150 million from the process) is expected to result in efficient processing of claims of lesser value.

Claims valued at over $150 million are currently removed from the specific claims process. The process for addressing large-value claims is through the Cabinet process as claims valued at over $150 million require the Minister to obtain a discrete mandate approved by Cabinet prior to being accepted for negotiations.

1.2.3. Objectives

The primary objective of the specific claims policy is to discharge outstanding lawful obligations against the federal government through negotiated settlements. The overall objective of the Specific Claims Action Plan is to ensure that specific claims are resolved with finality in a faster, fairer and more transparent way.

1.2.4. The specific claims process under the Action Plan

Stage 1: Claims submission and early review

The specific claims process begins when a First Nation submits a claim submission. Within six months of submission, claims undergo an initial review (involving the Specific Claims Branch and the Department of Justice Canada) in which they are assessed against a minimum standard. If a claim meets this minimum standard, it is filed with the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and written notice of the date that the claim was filed is provided to the First Nation. If the claim does not meet the minimum standard, the First Nation is notified and an explanation is provided. The Minister can request missing information from the First Nation. At this stage, the First Nation is entirely responsible for ensuring that the claim submission is complete and accurate, and capable of meeting the minimum standard.

Stage 2: Research and assessment

The date the claim is filed with the Minister marks the beginning of a three-year research and assessment period in which the Minister decides whether to accept the claim for negotiation. During this stage, members of the Specific Claims Branch review the historical record of the alleged breach in relation to the claim. A package, containing the claim and relevant additional research is then submitted to the Department of Justice for a legal opinion. At this point, legal counsel for the Department of Justice involved in the review of specific claims assess whether the claim gives rise to an outstanding lawful obligation on the part of the federal government.

Stage 3: Recommendation and decision making

The claim, along with the historical review and legal opinion conducted in stage 2, is then presented to the Claims Advisory Committee for review. [Note 3] Within three years from the time the claim has been filed with the Minister, the Committee is expected to have made a recommendation to the Minister as to whether the claim should be accepted for negotiations, and the Minister to have notified the First Nation accordingly. In cases in which an outstanding lawful obligation has been found, it is ultimately the Minister who makes the final decision about whether the Government of Canada will enter into negotiations with the First Nation.

If the Minister fails to respond to the First Nation within three years, or if the Minister chooses not to negotiate the claim, the First Nation has recourse through the Specific Claims Tribunal. The Tribunal has the power to issue a binding decision concerning the validity of the claim and to award compensation of up to $150 million per claim.

Stage 4: Negotiation and settlement

In cases where First Nations are notified of the Minister's decision to negotiate, a three-year negotiation period begins. First Nations, Specific Claims Branch representatives, and any other parties added to the claim enter into negotiations. If necessary, mediation services may be used during this period to facilitate negotiations.

Ideally, a final settlement offer will be made to the First Nation regarding the claim. The Specific Claims Tribunal Act does not require that negotiations be completed within three years; however, if a settlement is not reached within three years of the date that the claim was accepted for negotiations, the First Nation may file the claim with the Specific Claims Tribunal, seeking settlement through the Tribunal rather than through continued negotiations.

1.2.5 Program management, key stakeholders, and beneficiaries

Governance

The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the Treaties and Aboriginal Government Sector within INAC is responsible for ensuring the Specific Claims Action Plan is operated and managed effectively with appropriate use of human and financial resources. This accountability also extends to monitoring and assessment activities.

The Specific Claims Branch of INAC is responsible for the implementation and administration of the Specific Claims Action Plan. Specific responsibilities include:

- Receiving specific claim submissions from First Nations and assessing them against the minimum standard;

- Filing specific claims that meet the minimum standard with the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development;

- Making recommendations to the Minister as to whether a claim should be accepted for negotiation;

- Negotiating the settlement of specific claims with First Nations;

- Monitoring and assessing negotiating tables and reporting results regularly;

- Formulating financial mandates to settle specific claims;

- Paying settlements negotiated by INAC and monetary awards issued by the Specific Claims Tribunal;

- Administering the specific claims settlement grant; and

- Collecting performance data and reporting results.

The Department of Justice Canada provides advice as to whether a claim gives rise to an outstanding lawful obligation on the part of Canada. It also provides advice on financial mandates that are submitted to the Claims Advisory Committee for consideration. It provides legal advice to INAC during the negotiation process. Finally, the Department represents Canada before the Specific Claims Tribunal.

Key stakeholders and beneficiaries

The following entities and organizations can benefit from the resolution of specific claims:

- First Nations – greater certainty over lands and natural resources, cash and land settlements that may support community development, and resolution of injustice;

- Federal departments – INAC, the Department of Justice Canada, the Department of Finance, and the Treasury Board Secretariat through the clarification of roles and responsibilities with additional resources to implement the Specific Claims Action Plan;

- Provincial and territorial governments – greater certainty over lands and natural resources;

- Aboriginal representative organizations – resolution of injustice;

- Local governments adjoining First Nation communities – improved relationships and enhanced ability to make plans respecting land management and natural resources; and

- Private sector – improved confidence in their business and investment decisions respecting First Nation interests in lands and natural resources.

1.2.6 Program resources

Resources in the amount of $67,931,430 (O&M for INAC and the Department of Justice); and $1,596,016 (Accommodation).

The Cabinet approved funding in the amount of $250 million annually, for ten years, with funding for the five-year period ending in 2013–2014 reflected as an "ongoing" amount. This funding is to be used to pay out settlements up to $150 million per claim, and to recover any monies loaned to First Nations to support negotiations. In addition to this dedicated fund, the Action Plan has other financial and human resources available including:

- Operating expenditures – This includes incremental funding to support the hiring of staff. INAC, as well as the Department of Justice Canada, anticipated a need for additional full-time employees to support the implementation and administration of the Specific Claims Action Plan. The Specific Claims Branch aimed to hire 31 new full-time employees including additional negotiators, researchers and analysts, and portfolio managers. In addition, the Department of Justice Canada intended to employ a total of 25 new full-time employees including legal professionals, paralegals, and support staff.

- Contribution funding – INAC provides non-recoverable contributions to First Nations to help them research their specific claims and, if necessary, to bring their claims before the Tribunal.

- Loan funding – INAC provides recoverable loans to support First Nation claimants in the negotiation process. The loans are repaid against compensation received from Canada, either through successful negotiation or through decisions by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

- Mediation funding – Canada will bear the cost of independent mediation services at specific claims negotiation tables. Funding in the amount of $5 million over four years is available to support the provision of independent mediation services. This amount is in addition to the amounts previously noted and includes salaries, benefits, Public Works and Government Services Canada set-offs and grants and contributions.

- Registry of the Specific Claims Tribunal – The Registry of the Specific Claims Tribunal will gain access to funding once a Parliamentary vote has been established. In the interim, INAC has agreed to provide funding for the registry.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation scope and timing

This formative evaluation of the Specific Claims Action Plan focussed on activities that occurred between 2007 and the present. As the focus of the evaluation is on the Action Plan – not the entire specific claims process – the Specific Claims Tribunal and the Specific Claims Tribunal Registry were not included in the scope of the evaluation. While the Specific Claims Tribunal was formed as a result of the Action Plan, it is an independent quasi-judicial body and the activities of it and its Registry are beyond the direct influence of the Action Plan.

Terms of Reference for this study were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) on July 28, 2010. Fieldwork was conducted between September 2010 and January 31, 2011.

2.2 Evaluation issues and questions

The evaluation focussed on assessing the relevance, design and delivery, efficiency and economy, and successes and early outcomes of the Specific Claims Action Plan. The following table details the evaluation questions and indicators.

- The establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal's infrastructure and Registry;

- Establishment and operation of mediation services for First Nations who are negotiating their specific claim with Canada;

- Complete review and assessment of all existing specific claims by October 16, 2011;

- Increase the number of negotiation tables from 100 to 120 annually; and

- Increase the number of specific claims that are successfully resolved through negotiations or through a hearing conducted by the Specific Claims Tribunal.

2.3 Evaluation methods

The results of the evaluation are supported by findings that were collected using a number of research methods. This subsection describes these various methods, along with a discussion on the rationale for these methodological choices, and the challenges faced during the study.

2.3.1 Document and data review

The document and data review constituted a significant source of information for this evaluation. It included a thorough review of background documents, INAC publications related to the Action Plan, and performance measurement materials.

2.3.2 File review

A total of 30 specific claims files were reviewed as part of this process. The selection of these files was done randomly, while taking into account a number of criteria. The first criterion considered was the regional distribution of files. The second criterion considered was the status of the files. Out of the 12 possible file statuses, four of them were retained: active (ACT), legal opinion stage (DOJ), research (RES), and settled through negotiations (SET). These statuses are the most relevant for the purpose of this evaluation. Finally, the third criterion considered was the typology of the files. There are a total of nine types of claims, including treaty land entitlement, surrenders and alienation and damages caused by a third party. Files were randomly selected from a variety of types, taking into account their current status date.

The purpose of the file review was to gain an understanding of the range of issues that stakeholders are facing in dealing with specific claims, and particularly those issues that could have a significant impact on the timeframe required to settle the claim. It is important to note that the file review did not focus on the actual claims themselves but rather on the process associated with each claim. Also worth noting is that the vast majority of files reviewed were initiated before the implementation of the Action Plan.

2.3.3 Literature review

The literature review examined similar experiences in Canada and in other jurisdictions which include: September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, United States; United Nations Compensation Commission; Treaty of Waitangi Claims Process, New Zealand; National Native Title Process, Australia; Indian Residential Schools Independent Assessment Process, Canada; and the Métis Settlement Appeal Tribunal, Alberta, Canada.

The literature review examined key features and processes followed by each of these initiatives. It included a comparative analysis, highlighting differences between these alternative resolution processes, and a review of the applicability of these approaches to the specific claims process.

2.3.4 Key informant interviews

The key informant interviews addressed all of the questions structuring the evaluation. These questions were developed to aid in the assessment of the rationale and relevance, design and delivery, efficiency and economy, and success and early outcomes of the Action Plan.

A total of 31 interviews were conducted with 33 key informants from the following groups:

- INAC senior management (n=6)

- INAC Specific Claims Branch (n=12)

- The Department of Justice (n=2)

- The Specific Claims Tribunal (n=1)

- Provincial government departments involved with processing or negotiating specific claims (n=6)

- First Nations organizations and their legal counsel (n=6)

Separate interview guides were developed for each group of representatives so that questions were tailored to each respondent's area of expertise. Interviewees were provided with a copy of the interview guide, in both official languages, prior to the interview. Each interview was conducted in the respondents' preferred language. Key informants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses.

2.3.5 Considerations, strengths, and limitations

The methodology used for this evaluation was structured to allow for a thorough review of documented or undocumented facts about the program, and for the gathering of opinions and perceptions of all key stakeholders involved in the specific claims process, including representatives from First Nation communities and organizations, relevant provincial and federal government departments, and INAC.

Since the evaluation relied heavily on qualitative data, qualitative data analysis software (NVivo) was used to systematically structure the findings and allow for a complete integration of all qualitative lines of evidence.

The database that the Specific Claims Branch is managing offers a detailed history of each claim and proved useful for the file review and in analysing the overall history of specific claims since 1973.

One challenge encountered during this evaluation related to scheduling key informant interviews. A few key informants on PRA's contact list declined to be interviewed, and some (a minority of key informants overall) required interviews to be rescheduled one or more times, delaying data collection for this line of evidence. Another limitation of this study is the fact that legal opinions could not be reviewed, as this information is protected by solicitor-client privileges.

It should be emphasized that these methodological challenges did not substantially affect the data collection process or the validity of the findings presented in this report.

2.4 Roles, responsibilities, and quality control

EPMRB and PRA worked collaboratively during the design, data collection, and analytical phases of this evaluation study. To this end, they benefited from the support of an advisory committee comprising representatives from the Specific Claims Branch and the Department of Justice Canada. The Advisory Committee was responsible for:

- reviewing the evaluation assessment outlining the evaluation questions and indicators, methodology for data collection and analysis;

- helping to identify critical resource materials and data sources and facilitating access to them;

- helping identify individuals according the methodology and facilitating access to them;

- participating in a presentation of validation of findings and assisting with the interpretation and contextualization of those findings; and

- reviewing and providing comments on evaluation reports.

Furthermore, in-line with EPMRB's Quality Assurance Strategy, internal peer reviews on the Methodology Report and this report were conducted to ensure the reports are clearly and concisely written and are compliant with applicable policies.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

Resolving specific claims is a longstanding, yet challenging goal for both the federal government and First Nations. The Action Plan aims to improve this process. This section of the report explores the consistency of the Action Plan with federal roles and responsibilities, the set of challenges that the specific claims process faced at the time of the Action Plan release, and the rationale for proceeding with the implementation of the Action Plan's four pillars.

3.1 Consistency of federal roles and responsibilities

At its most fundamental level, specific claims relate to the fulfillment of the Crown's outstanding lawful obligations toward First Nations and to obligations established in treaties. In the particular context of First Nations, treaties stand as the most sacred of agreements between two parties, meant to define their long-term relationship. It is widely recognized that treaties between First Nations and the Crown have played a predominant role in the establishment and expansion of Canada. [Note 4]

From time to time, the federal government has failed to uphold its lawful obligations relating to the administration of land and other First Nation assets, or relating more generally to the fulfilment of treaties signed between the Crown and First Nations. As a result of these breaches, First Nations have submitted claims to the federal government seeking redress. It is these claims that have come be known as "specific claims." [Note 5]

It is undoubtedly in the best interest of the federal government, let alone First Nations, to settle specific claims. As the Supreme Court of Canada stated, "in all its dealings with Aboriginal peoples, from the assertion of sovereignty to the resolution of claims and the implementation of treaties, the Crown must act honourably." [Note 6]

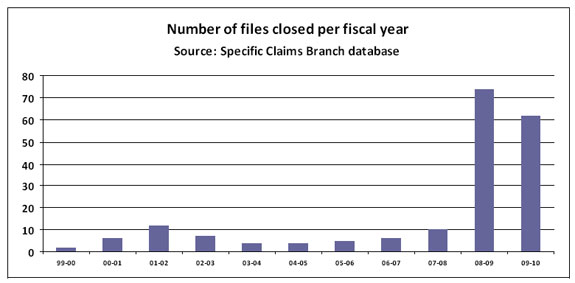

To this day, First Nations have submitted close to 1,500 claims to the federal government. While the validity of all these claims have not been formally established, this number provides a clear indication of the volume of claims faced by the federal government. Table 1 (next page) provides an overview of claims submitted to date and their current status. Just over 500 claims are currently in progress, under the various components of assessment or negotiation. Of the close to 900 files that are now closed, just over 340 have been settled by negotiations and just over 500 have been concluded because the federal government decided that no lawful obligation had been breached or that the file had been closed due to various reasons.

| Status | # of claims | |

|---|---|---|

| In progress (n=527) |

Under assessment | |

| Research | 49 | |

| Department of Justice preparing legal opinion | 144 | |

| Legal opinion signed | 164 | |

| Subtotal | 357 | |

| In negotiations | ||

| Active negotiations | 147 | |

| Inactive negotiations | 23 | |

| Subtotal | 170 | |

| Concluded (n=889) |

Settled through negotiations | 343 |

| No lawful obligation found | 263 | |

| Resolved through administrative remedy | 33 | |

| File closed | 250 | |

| Subtotal | 889 | |

| Other | Active litigation | 77 |

| Grand total | 1,493 | |

Source: Specific Claims Branch database.

Since the formal establishment of a Specific Claims Policy in 1973, the federal government has provided an alternative dispute resolution option for settling outstanding claims. This remains a priority ofthe federal government, as articulated in the most recent Speech from the Throne [Note 7], as well as in the Action Plan itself:

The Government of Canada is accountable for legally-binding treaties and agreements signed by previous governments between the Crown and First Nations and has a duty to honour past commitments made with First Nations. Centuries may have passed since a treaty was signed, this does not diminish Canada's obligation to keep its promises. [Note 8]

The Specific Claims Tribunal Act further entrenched this commitment, stating that "it is in the interests of all Canadians that the specific claims of First Nations be addressed," and that "resolving specific claims will promote reconciliation between First Nations and the Crown and the development and self-sufficiency of First Nations." [Note 9]

3.2 Challenges that the specific claims process faced at the time of the Action Plan release

When dealing with a specific claim, both the federal government and First Nations favour a negotiated settlement, rather than engaging in adversarial procedures before the courts. As stated in the revised Specific Claims Policy in 1982, "negotiation (...) remains the preferred means of settlement by the government, just as it has been generally preferred by Indian claimants." [Note 10] This continues to be the formal policy stand of the federal government. [Note 11]

At the time the federal government announced the Action Plan in 2007, complex issues had led to significant backlogs and fed an increasing level of frustration among all stakeholders involved, particularly among First Nations. The set of challenges that the specific claims process faced at the time of the Action Plan release are described below.

3.2.1 Developing a claim

It is the norm, rather than the exception, that claims submitted by a First Nation involve complex issues that unfold over an extensive period of time and may not have been systematically documented. When submitted to INAC, these claims often include hundreds of pages of documentation, going back to the early 1900s or earlier. As noted in the Action Plan, when dealing with specific claims, it "can be very difficult to establish the facts, a process that is both time consuming and costly." [Note 12]

Particularly during the period that followed revisions to the specific claim process in 1982, INAC and First Nation claimants typically worked jointly to establish the facts relating to a specific claim. More specifically, the process at that point in time entailed the following steps:

- Once a First Nation had submitted its claim, the Specific Claims Branch would review it to ensure that it fell within the parameters of the Specific Claim Policy (as established in 1973).

- In cases where a claim fell within these parameters, the Branch would then identify any issue or question that would require further research or clarification and would undertake the research. Once the Branch was satisfied that all the required information and data had been gathered, it would prepare a historical report, which it would then send to the First Nation for review and approval.

- Once reviewed by both the Branch and the First Nation, the claim would be sent to the Department of Justice Canada to prepare the required legal opinion.

This process was beneficial in that it allowed INAC and the First Nation to jointly build a claim that would be considered complete, accurate, and thorough. The obvious downturn to this approach was the time needed to reach that stage. The 30 files reviewed as part of this evaluation provide a good illustration of this. On average, it took over two years for these claims to be sent to the Department of Justice Canada. While some of these claims were sent after six or eight months, others took five, seven, or nine years before they were sent for a legal opinion. These substantial delays were due to the complexity of the additional research needed, as well as the time required for a First Nation to review and approve the historical report.

3.2.2 Producing legal opinions

Over time, one of the most problematic components of the specific claims process has proven to be the preparation of the initial legal opinion whose purpose is to determine whether a lawful obligation had been breached. The complexity of specific claims, the nature of solicitor-client relationship, and the limited resources available to the Department of Justice Canada to undertake this task have all contributed to this outcome.

During the period preceding the Action Plan, several years would often lapse between the time the Department of Justice Canada would receive a claim and the date it would submit its legal opinion. Among the 30 files reviewed as part of this evaluation, there were cases where three, five, seven, or eleven years separated those two milestones. One of the key drivers behind these delays was simply the limitation of resources available within the Department of Justice Canada to prepare these opinions. The fact that a claim was transferred to the Department of Justice Canada did not mean that legal counsel would be immediately assigned to the file. On the contrary, legal counsel working on these claims typically had a list of priorities, meaning that several claims would be left in the queue before they could be addressed. At one point, the Department of Justice Canada had approximately 350 claims that awaited to be assigned to a legal counsel, creating a backlog that spanned over many years. Once legal counsel had been assigned to the file, they would require considerable time to review all the material submitted, consider all the applicable case law, and write what were often lengthy legal opinions which needed to be reviewed internally within the Department of Justice Canada before they could be submitted to INAC. This is a process that could require several months.

Moreover, one unique characteristic of the legal opinion process is that it systematically excludes the First Nation claimant. At that stage of the process, the relationship between the Department of Justice Canada and INAC is essentially a solicitor-client relationship that is privileged and, therefore, excludes all external parties, whether it is a First Nation, a provincial government or another federal department. It should be noted that, along the same logic, the relationship between a First Nation claimant and its legal counsel is privileged, therefore excluding systematically any third party, including the federal government. This stood in contrast with the preparation of the claim, whereby INAC and the First Nation claimant would interact, exchange information, and communicate updates on an as needed basis. Once the claim had been transferred to the Department of Justice Canada for a legal opinion, the First Nation had very little option but to wait for the opinion to be completed, and while INAC could interact with the Department of Justice Canada, it could not dictate how the work would be done. Not surprisingly, evidence gathered as part of this evaluation confirms that delays associated to the legal opinion process, more than any other types of delays, triggered the highest level of frustration among First Nations.

The one scenario, during the pre-Action Plan period, where the legal opinion process could be accelerated was for claims worth $500,000 or less. In these cases, the Department of Justice Canada would prepare an expedited legal opinion as part of what was labelled a "fast track" stream. Even then, delays incurred as a result of the backlog of files could still generate significant impediment to the completion of this portion of the process.

3.2.3 Internal procedures within First Nations

Some First Nations have needed considerable time to complete some of the steps required as part of the specific claims process. The first area that proved challenging for some First Nation claimants was the review and approval of the historical report, which was to be transferred to the Department of Justice Canada. Among files reviewed as part of this evaluation, there were instances where First Nation claimants took several years to respond to the Specific Claims Branch. The other area of contention is the Band Council Resolution needed, when the federal government has accepted a claim (entirely or partially), to proceed with the negotiation. Here again, evidence gathered as part of this evaluation indicates that several months, and sometimes years, may be required to obtain this Resolution. Changes in the leadership of the Band Council or other more pressing issues appear to have caused these delays.

3.2.4 Technical studies

Technical studies, typically required during the negotiation process, had, from time to time, significantly slowed down the negotiation process. Typically undertaken jointly, these studies may have involved land appraisals, environmental assessments, loss of land uses, or other types of valuation. Evidence gathered as part of this evaluation indicates that even agreeing on the proper terms of reference to frame these studies sometimes took several months, and in some cases a number of years.

3.2.5. Involvement of other stakeholders

While First Nation claimants, INAC, and the Department of Justice Canada are the primary stakeholders when it comes to addressing a specific claim, there are other stakeholders whose direct involvement may be required to settle a valid claim.

- Provincial governments may participate in the specific claims process. Their interest may stem from a particular file that deals with a flooding claim, a treaty land entitlement, a claim that involves land currently owned or used by a province (for road or parks purposes for example), or a pre-Confederation claim [Note 13].

- Private interests may be involved in the settlement of a claim. These include companies that have acquired land that is now the object of a claim and, in some cases, have built infrastructure that are now located on disputed land.

- Some claims also require the involvement of other federal departments such as Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

In the particular case of provincial governments, their involvement may be required to provide the land necessary for settling a specific claim. In a number of these provinces, procedures to deal with specific claims have been established, and these may or may not align with the federal framework, particularly as it relates to the expected timeframe to complete certain portions of the specific claims process.

3.2.6 The perceived imbalance

One aspect of the specific claims process that has consistently been debated is the perceived imbalance it creates between the federal government and First Nations. Put simply, the federal government is seen as the entity that establishes the framework for addressing specific claims in a non-judicial setting, determines independently whether a claim gives rise to a lawful obligation owed to a First Nation, and determines the process to be followed to provide compensation. Some have characterized this relationship has representing an "inherent conflict of interest in the claims process, a process in which it was both a party and a judge." [Note 14]

Over time, this particular framework has proved challenging, particularly in cases where the federal government concluded that no lawful obligation had been breached and, consequently, no negotiation would be entertained. At that point, the First Nations that disagreed with this decision would be left with no other option but to undertake what would typically be lengthy and costly legal proceedings before the courts. The context changed in 1991 when the federal government established, as in interim measure, the Indian Specific Claims Commission whose mandate was to conduct public inquiries and offer mediation services to the parties. By the time it ceased its operations in March 2009, the Commission had completed 88 inquiries and 17 mediations. [Note 15] While systematically considered by INAC, the recommendations from the Commission were not binding.

3.3 Rationale for proceeding with the implementation of the four pillars

By the time the federal government tabled its Action Plan in 2007, the specific claims process was under enormous stress. There were close to 800 outstanding claims, the vast majority of which where under review and assessment or awaiting a legal opinion. The timeframe for resolving a claim averaged 13 years, and First Nations were submitting two times more claims each year than were resolved. The fairness of the system continued to be questioned, and human resources were increasingly stretched with little hope of relief in the foreseeable future. [Note 16]

The scope of the Action Plan, as articulated through its four pillars, appears adequate to address the most pressing issues that have negatively affected the specific claims process. Findings gathered as part of this evaluation found support for the current scope among representatives of INAC, the Department of Justice Canada, and First Nations.

While the four pillars may be expected to improve the specific claims process, the fact remains that a number of factors, such as procedures within First Nation communities or the involvement of provincial governments, fall beyond the control of INAC. Even the extent to which the Department of Justice Canada will be able to improve the efficiency of its process for delivering comprehensive yet timely legal opinions rests largely beyond INAC's control. As a result, the rationale for proceeding with the implementation of the four pillars may be sound, but the extent to which the Action Plan will reach its fundamental objectives will require the contribution of a range of stakeholders with whom INAC will unavoidably have to interact.

It is worth noting that Canada is not the only country facing challenges when it comes to settling specific claims. For instance, in New Zealand, the Office of Treaty Settlements operates much like the Specific Claims Branch, dealing with claims relating to breaches to the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between the Māaori and the Crown. In 1975, New Zealand established the Waitangi Tribunal, which has been given "exclusive authority to determine the meaning and effect of the Treaty as embodied in [the Treaty's Māori and English texts] and to decide issues raised by differences between them." [Note 17] Struggling with inefficiencies and a backlog of claims, the Tribunal adopted, in 2001, a New Approach to streamline the Waitangi Tribunal's process by implementing new timelines to shorten the inquiry and settlement process. In 2005, the Waitangi Tribunal announced its objective to settle all historical claims by 2020. [Note 18]

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

This section of the report summarizes findings related to the implementation of the four pillars of the Action Plan as well as examines monitoring and performance measurement under the Action Plan.

4.1 Pillar 1: The Specific Claims Tribunal

Arguably, the establishment of the Specific Claims Tribunal may be considered the most significant component of the Action Plan. This marks the end of a longstanding debate in Canada on whether an independent tribunal should be established to deal specifically with those breaches now included under the concept of specific claims. This milestone also marked the end of the Indian Specific Claims Commission, the interim measure that the federal government had implemented in 1991.

4.1.1 Establishment of the Tribunal

The federal government has succeeded in establishing the foundation allowing the Tribunal to operate. Parliament passed the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, which came into force on October 16, 2008, just a little more than a year after the release of the Action Plan. It should be noted that INAC and the Department of Justice worked jointly with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) to draft the initial bill that was submitted to Parliament. This is an efficient timeframe considering the complexity of the matter. The Act covers all aspects of the operation of the Tribunal and the Registry of the Specific Claims Tribunal.

The federal government also proceeded to the appointment of judges to be assigned to the Tribunal. The facts leave no doubt that this process has proven to be challenging. It took two and a half years following the launch of the Action Plan, and more than a year after the Act had been passed, for the federal government to appoint the chairperson and two full-time Members to the Tribunal. Interviews conducted as part of this evaluation confirm that it has proven difficult to convince Superior Court judges to move into these positions.

INAC has also completed the steps required to establish the Registry of the Specific Claims Tribunal. The Department provided funding for the operations of the Registry up until the end of fiscal year 2008–2009.

The Tribunal is a stand alone, arms-length adjudicative body. The Tribunal has its own budget and is fully accountable to Parliament for its expenditures and operations. The Tribunal is also responsible for preparing its own annual reports to keep the Government and all Canadians up-to-date on its activities. As public funds are involved, there must be a Minister responsible to Parliament. As set out in the legislation, the annual reports will be tabled in the House of Commons by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Registry was established as a separate federal department under the Financial Administration Act. The Registrar is the Deputy Head of the Department. It is independent from existing government departments, but forms part of the federal public administration to ensure financial accountability.

At the time of this evaluation, the Tribunal was still in the process of establishing its rules and procedures and, to this end, held consultations with various stakeholders, including INAC, the Department of Justice Canada, and First Nation representatives. Since the actual work of the Tribunal falls beyond the mandate of this evaluation, no assessment of the content, quality, or appropriateness of these rules and procedures has been completed. Suffices to say, all stakeholders closely monitor the development of these rules and procedures as they will have a significant impact on the operation of the Tribunal.

4.1.2 Benefits of the Tribunal

The very establishment of the Tribunal represents a significant achievement. It largely puts to rest concerns that INAC was both a party and a judge in the specific claims process. Literature reviewed as part of this evaluation indicates this may well be the first such Tribunal to be established in the world to deal with claims related to treaties signed between the Crown and Aboriginal groups. The Tribunal can be expected to contribute to the fair resolution of claims by establishing a significant case law and building a body of knowledge on specific claims.

The other significant benefit of the Tribunal process is the fact that no considerations relating to any statutes of limitation or to the doctrine of laches (unreasonable delays) can be considered in any claims submitted to the Tribunal. This, again, puts to rest a fair amount of speculation on the extent to which these theories may be applicable to specific claims that, by their very nature, are often traced back over many decades.

4.1.3 Impact on stakeholders

The establishment of the Tribunal is bound to transform the role of INAC, the Department of Justice Canada, and First Nations. Both parties (the Crown and First Nations) will need to build the capacity to interact and make representations before this new structure. The extent of this impact is not known at this point since the Tribunal is not yet operational. Evidence gathered as part of this evaluation clearly indicates, however, that each party will need to find ways to direct new resources toward this function. In particular, First Nations remain uncertain whether appropriate funding will be available for them to adequately represent themselves before the Tribunal.

4.2 Pillar 2: Specific Claims Settlement Fund

The federal government has succeeded to establish a fund specifically dedicated to specific claims. A total of $250 million per year, for 10 years, is now available to cover settlements up to $150 million per claim and for Specific Claims Tribunal awards. This replaces an annual funding of $30 million that the federal government used to set aside for specific claims.

The experience to date under this new model points to a number of benefits. First, the fund sends a clear message that the federal government is putting aside substantial amounts of resources to address specific claims. Second, knowing this volume of resources is available appears to be facilitating the work of the Specific Claims Branch in planning and managing its various negotiation tables. For any given year, the Specific Claims Branch does not need to plan for alternative sources of funding, as long as the total settlement dollars required does not exceed the yearly allocation of $250 million. It should be noted that funds not used during one particular fiscal year may be re-profiled to the following fiscal year, funds may also be drawn from future year allotment, and that claims over $150 million are expected to be funded through the fiscal framework, and not through this set aside fund.

While the dedicated fund appears to facilitate access to financial resources, the fact remains that a fairly lengthy process involving central agencies still needs to occur for any claim over $7 million. For those, the Specific Claims Branch still needs to prepare a Treasury Board Submission, which mobilizes important resources. In order to have a coherent approach, it is worth noting that the Specific Claims Branch has created a Mandating and Valuation Unit for the purpose of providing expertise, experience, support, and consistency in the review and provision of advice to the development and approval of financial mandates as well as assessing and attributing values to specific claims. The portfolio also provides oversight, tracking, projecting, and plays an advisory role in the management of the annual settlement budget and payments made from that budget.

In addition, as reported by key informants as part of this evaluation process, there is a considerable amount of speculation about whether the total amount of $2.5 billion over 10 years will be sufficient to settle all specific claims. Again, this is largely a theoretical issue, particularly in the early stages of the Action Plan's implementation. It is worth noting that even if the $2.5 billion would fall short of the level of resources required, the federal government would still need to face its liabilities and find ways to free up the required resources.

4.3 Pillar 3: Mediation services

The Action Plan states that "mediation is an excellent tool that can help parties in a dispute to reach mutually beneficial agreements. Canada recognizes that this tool should be used more often in stalled negotiations and is committed to increasing its use in the future." [Note 19] However,mediation is the one component of the Action Plan where the least progress has been achieved thus far. Evidence gathered as part of this evaluation points to challenges at three different levels:

- The initial goal under the Action Plan was to modify the mandate of the Indian Specific Claims Commission in order to allow the Commission to provide mediation services. For legal and technical reasons, this has not proven possible forcing the Specific Claims Branch to explore alternative strategies. [Note 20]

- Findings from the evaluation conclude that the Specific Claims Branch has yet to clearly articulate which circumstances INAC negotiators would consider a mediation process.

- The process to build a roster of mediators has begun. At the time of the evaluation, INAC was expected to launch a process on MERX to build this roster. INAC has invited the AFN to represent the interests of First Nations in the development develop the mediator selection criteria and other aspects of the creation and implementation of the roster. However, INAC and AFN have not found common ground in which to jointly proceed with these matters.

Representatives from First Nation organizations noted that, while some discussions were held with INAC in the early stages of the Action Plan implementation in regards to mediation services, they are now largely excluded from the process leading up to the selection of mediators. This, in turn, could negatively affect the willingness of First Nations to agree to a mediation process.

4.4 Pillar 4: Internal Governmental Procedures

This section examines internal government procedures under the action plan as per the research and assessment phase, the negotiation and settlement phase, as well as procedures for claims over $150 million.

4.4.1 Research and assessment

As a result of the Action Plan, and more specifically, the passing of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act, INAC has reviewed its internal procedures relating to the research and assessment of a claim, leading up to the written notification of the Minister's decision on whether to negotiate the claim. [Note 21] As noted in the description of the Action Plan, the Minister is expected to inform a First Nation on whether an offer to negotiate will be made within a period of three years from the time the claim has been filed with the Minister. In cases where the Minister would fail to notify a First Nation on whether negotiation will be offered, the First Nation has the opportunity to turn to the Tribunal, which would then determine the validity of the claim and order a compensation.

Minimum standard

One of the most significant changes in the review and assessment stage of the specific claims process is the implementation of a minimum standard requirement "in relation to the kind of information required for any claim to be filed with the Minister, as well as a reasonable form and manner for presenting the information." [Note 22]