Archived - Evaluation of the Federal Government's Implementation of Self-Government and Self-Government Agreements

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

* Table figures for On-Reserve Population retrieved from INAC website. First Nations Profiles: Registered Population (current to July, 2010). On-Reserve figures include males and females living on other reserves.

* Table figures for student enrolment were retrieved from Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey nominal roll submitted to INAC for the 2009-2010 school year.

In addition, the Agreement supports both on and off reserve Mi'kmaq Nova Scotians enrolled in post secondary studies. In 2008-2009, there were 496 post-secondary students supported under the Agreement.

History of Negotiations

In recognition of the vital importance of education to the future of the Mi'kmaq Nation, in 1991 the Assembly of Nova Scotia Chiefs approached INAC and proposed that a Mi'kmaq Education Authority be established for the devolution of federal education programming to the thirteen Mi'kmaq communities in Nova Scotia. In June 1993, the chiefs changed their request from the transfer of the responsibility to administer education on reserve from INAC to a complete transfer of Canada's jurisdiction over education on reserve. This jurisdiction includes the power to make and administer laws and regulations with respect to primary and secondary education, and law-making powers with the respect to the administration and expenditure of community funds in support of post-secondary education, enabling the thirteen Mi'kmaq communities to assume full legal responsibility and control over First Nations education in Nova Scotia. Their request was met with an agreement from Canada to commence negotiations, which formally began in 1994 when a political accord was struck between the parties. In December of 1996, A Tripartite Agreement between First Nations, the Province of Nova Scotia and Canada was signed, affirming Nova Scotia's acknowledgement of Mi'kmaq jurisdiction. Federal and Provincial legislation (Bill C-30 and Bill no.4 respectively) were enshrined in federal and Nova Scotia Law in 1999, giving force to the Agreement with Respect to Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia (the Agreement) between nine of the thirteen Mi'kmaw bands and Canada.

The Agreement with Respect to Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia

Jurisdiction with respect to Mi'kmaw education is exercised by individual First Nations in accordance with the Agreement. In addition to the transfer of law-making and administrative authority for primary and secondary education on reserve, and law-making power with respect to the administration and expenditure of community funds in support of post-secondary education, the Agreement removes participating communities from s. 114-122 of the Indian Act and provides for the harmonization of Mi'kmaw, federal and provincial laws over education. In addition, the Agreement provides for the establishment of education boards and outlines the standard of education to be provided for by participating communities. The Agreement states "the participating communities shall provide primary, elementary and secondary education programs and services comparable to those provided by other education systems in Canada, so as to permit the transfer of students between education systems without academic penalty, to the same extent as the transfer of students is effected between education systems in Canada" (s. 5.4).

The Agreement is supported by a separate five year funding agreement that is renegotiated and renewed normally during a five year cycle. Through the Funding Agreement, INAC transfers an annual grant to participating communities through a single administrative body (Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey – MK) for capital repairs and replacement, second level services as well as governance. The amount of the annual grant is adjusted annually for price and volume and is distributed on a quarterly basis. The current agreement took effect in 2005/06 and established an annual transfer of $29,063,977 (base amount). A one year extension to the current agreement was established in March 2010. It is anticipated that the renewal of a successor (3rd) funding agreement will be complete by March 31, 2011.

MK also receives addition funding for INAC-targeted education programs through contribution agreements which are separate from the grant. There are currently nine targeted programs that MK applies to, on behalf of communities:

- Elementary/Secondary Instructional Services – Band Operated Schools;

- Teacher Recruitment and Retention;

- Parental and Community Engagement Strategy;

- New Paths for Education;

- First Nations SchoolNet;

- First Nation Student Success Programs;

- Partnership Initiative – Education;

- Special Education/High Cost; and

- Youth Employment Strategy Program.

Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey (MK)

The objectives of the Agreement are to:

- Specify the procedures and instruments through which education jurisdiction of participating communities will be realized; and

- Determine the specific governance and administrative structures through which the participating communities will exercise jurisdiction with respect to education.

In fulfillment of these objectives, the Agreement provides for the creation of Mi'kmaw Kina'matnewey, a legally recognized corporate authority whose Board of Directors consists of the elected Chiefs from each participating community.

MK administers the Final Agreement with Respect to Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia and allocates funding to participant communities as provided for by the Funding Agreement (Schedule "A" of the main Agreement). The organization is led by and Executive Director who manages the education programming, finance and administration staff. MK does not have the authority to enact education laws as jurisdiction lies solely with the communities themselves. Only individual band councils may enact laws applicable to primary, elementary and secondary education programs and services in their respective communities.

MK serves as the collective voice in education for the ten participating communities. The primary purpose of MK is to identify the needs of the communities and to assist them in meeting common objectives in the delivery of education programs and services. The corporation takes its direction from the elected chiefs of the ten member communities who each occupy a seat on MK's Board of Directors. The Board, in turn, makes decisions on budgets and programming on the advice of several working groups comprised of the Directors of Education, principals and educators, community members as well as provincial and federal officials. The Agreement requires that MK establish a constitution, setting out the powers of the organization, the powers of the Board as well as general procedures for establishing budgets and funding allocation, voting, and a process for dispute resolution which includes the use of a traditional Mi'kmaq process called Nuji Koqajatekewinu'k.

As stated in their constitution, the objectives of MK are:

- To assist and provide services to individual bands in the exercise of their jurisdiction over education;

- To assist individual Bands in the administration and management of education for the Mi'kmaq Nation in Nova Scotia;

- To provide the Mi'kmaq Nation in Nova Scotia a facility to research, develop and implement initiatives and new directions in the education of Mi'kmaq people; and

- To coordinate and facilitate the development of short and long-term education policies and objectives for each Mi'kmaq community in Nova Scotia, in consultation with the Mi'kmaq communities. [Note 30]

In addition to supporting communities in the delivery of education programs and services, MK has established a number of key program areas in which they initiate and manage a range of small and large scale projects including the establishment of a web based Mi'kmaw language dictionary and the introduction of the student data gathering and monitoring system. Through an agreement with INAC, MK has also assumed responsibility as the Regional Management Organization for the Atlantic Canada's First Nation Help Desk, to deliver the First Nations SchoolNet Program (FNS). FNS provides First Nation schools in Nova Scotia with support and resources to manage information and integrate technology into education. The program also assists schools with Internet connectivity and in troubleshooting local area networks and connectivity problems through the Help Desk.

Through the Agreement, MK has the authority to negotiate tuition agreements and financial arrangements with the Province of Nova Scotia. In 2008, MK and the Province established the Master Education Agreement. The Master Agreement sets out the rate that MK contributes for students to attend public schools. The Master Agreement also includes provisions for enhanced services such as professional development, and provides for assessments of students both on and off reserve.

MK has also established partnerships with other organizations and institutions that support the enhancement of education services and programming in participant communities. For example, MK participates as a representative on the Education Working Committee of the Mi'kmaq-Nova Scotia-Canada Tripartite Forum. The purpose of the Forum is to discuss, investigate, negotiate and implement solutions to substantive issues of mutual concern and jurisdictional conflict. As a member of the Committee, MK assists in identifying issues through research and community engagement and brings them back to the forum for consideration. Other partnerships established by MK include research activities through St. Francis Xavier University, as well as culture and language activities with the University of Cape Breton program for Mi'kmaq Studies.

To set priorities and determine the direction of the organization from year to year, MK hosts an annual education symposium in which participating communities are invited to present their achievements from the past year, and communicate their specific education needs and priorities to MK and the Board of Directors. MK also reports on its own priorities, activities and expenditures through an annual report, a requirement set out in the terms of the Funding Agreement. [Note 31]

Community Initiatives

In addition to education programs and service support provided by MK, since the establishment of the Agreement, individual communities have taken up a number of initiatives to enhance education programming, particularly in the area of culture and language. For example, the communities of Membertou and Eskasoni have established Mi'kmaq Emersion programming. In Membertou, the program is offered to students beginning in Kindergarten through to Grade 2. In Eskasoni, this program is offered to students beginning in Kindergarten through to Grade 3. Other community initiatives include the development of Mi'kmaw language tools such as children's books, day care programs with Mi'kmaw language instruction, adult learning programs and attendance initiatives, among others. Through the Agreement, communities have also formed partnerships to plan, develop and implement community-specific programming. Information on these initiatives and other education activities are outlined in MK's Annual Reports and community websites.

5. Evaluation Findings: Relevance

The evaluation examined the relevance of the federal government's implementation of self-government by providing an assessment of the alignment of the goal of the IRP with government priorities, its consistency with federal roles and responsibilities as well as demonstration of continuing need.

Findings from the evaluation conclude that the goal of the IRP, to implement a process that will allow practical progress to be made and empower Aboriginal people to become self-reliant, remains highly relevant as the Policy provides a viable alternative to the Indian Act for Aboriginal communities wishing to negotiate self-government. The Policy supports federal government priorities as well as international norms towards greater recognition of the rights of Indigenous people to self-government. Moreover, the negotiation and implementation of self-government under the IRP is fully consistent with federal roles and responsibilities.

Self-government remains relevant to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Through the IRP, the Government of Canada recognizes the inherent right of self-government as an existing Aboriginal right under Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Policy provides the framework for negotiation for those Aboriginal communities wanting to exercise their inherent right.

Canadian courts recognize that Section 35 can include the right to self-government. However, the courts have set a high standard for proving the existence and extent of such a right. Findings from the evaluation suggest that the IRP has removed pressure from the courts to decide on this issue.

National Aboriginal organizations have been highly critical of the IRP. As well, Aboriginal governments have expressed difficulty in establishing a government to government relationship with the Crown. A review of the literature and discussions with First Nation community members point to an overall frustration with what has been accomplished under the IRP. Outstanding issues also include self-government as it applies to Métis off a land base and the link between self-government and historic treaties.

5.1 Alignment with Government Priorities

INAC negotiates and implements self-government agreements on behalf of the Government of Canada, with other federal departments being involved where self-government agreements involve their areas of responsibility or jurisdiction. The negotiations and implementation of treaties and self-government agreements are important contributors to INAC's overarching mandate and currently one of the department's priority areas. Self-government negotiations are linked to the Cooperative Relationships program activity within the Government strategic outcome as outlined in the 2011-12 departmental Program Activity Architecture. Self-government implementation is linked to the Treaty Management program activity.

These activities support INAC's priorities by fulfilling is obligations to Aboriginal people and building strengthened relationships through progress on governance and self-government. [Note 32] Self-government activities also support INAC priority of improving economic development and sustainability, as the IRP supports Aboriginal governments and institutions developing their own sources of revenue in order to reduce reliance on transfers from other governments.

The desire of Aboriginal peoples to be self-governing political entities can be fully realized only with a transformation in their capacity to provide for themselves. A nation does not have to be wealthy to be self-determining. But it needs to be able to provide for most of its needs, however these are defined, from its own sources of income and wealth. [Note 33]

Moreover, the negotiation and implementation of self-government supports international norms towards greater recognition of the rights of Indigenous people to self-government as expressed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, to which Canada became a signatory in November of 2010. As stated in Article 4 of the Declaration,

Indigenous peoples, in exercising their right to self-determination, have the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions. [Note 34]

5.2 Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The negotiation and implementation of self-government is fully consistent with federal roles and responsibilities. The IRP represents Canada's responsibility towards Aboriginal people under Section 91(24) and Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. As stated in the IRP,

The Crown has a unique, historic and fiduciary relationship with Aboriginal peoples of Canada. While the Government's recognition of an inherent right of self-government does not imply the end of this historic relationship, Aboriginal self-government may change the nature of this relationship. [Note 35]

5.3 Continuing Need

The IRP provides the framework for negotiation for those Aboriginal communities wanting to exercise their inherent right and provides a viable alternative to the Indian Act. The large number of tables negotiating self-government, currently there are 91 tables with 70 active tables and 21 inactive tables, reflect this demand.

The IRP serves as a tool to foster reconciliation of Crown and Aboriginal interests through negotiations rather then litigation. Canadian courts recognize that Section 35 can include the right to self-government. However, the Courts have set a high standard for proving the existence and extent of such a right. For example, in a leading decision on the issue (R. v. Pamajewon [1996]), the Supreme Court of Canada found that, even if Section 35 could include self-government rights, the particular Aboriginal community in that case was unable to prove the right to control gaming initiatives on its land. Findings from the evaluation suggest that the IRP has removed pressure from the courts to decide on this issue.

5.4 Aboriginal Perspectives

Self-government remains relevant to First Nations, Inuit and Métis. As noted by Aboriginal key informants, self-government supports:

...creating space in Canada's federal state for First Nation, Métis, and Inuit people to govern their own affairs. It is about creating room in post colonial Canada for the continuation of indigenous people.

...bringing Aboriginal people into the confederation in a distinct and meaningful way. Self-government means that Aboriginal Government becomes part of the governing structures of the country. [Note 36]

National Aboriginal organizations have however expressed strong concerns with the Inherent Right Policy and its implementation. The IRP is perceived as a federal government policy that did not include Aboriginal input into its development and that negotiations with Métis groups without a land base has been limited.

The existing inherent right policy was developed unilaterally by thefederal government contrary to what the Supreme Court of Canada has been declaring with respect to consultation, the fiduciary relationship and reconciliation. The policy has been rejected by First Nations and has not produced the desired results, therefore, needs to be revisited in its entirety. [Note 37]

Although the policy clearly indicates that Métis are to have access to the policy and that resulting rights in agreements (with provincial support) can be protected as constitutionally-protected Section 35 rights, federal negotiators have refused to enter into substantive discussions on implementing self-government off a land base. [Note 38]

The link between self-government and historic treaties is also an outstanding issue. For example, in Saskatchewan, governance arrangements for the province's Treaty First Nations led to an Agreement-in-Principle and Tripartite-Agreement-in-Principle in 2003 though an impasse on negotiations was reached and these agreements were not ratified. The reasons are documented in the Office of the Treaty Commissioner report on treaty implementation and include:

What is missing, both in the federal government's 1995 "Inherent Right Policy" and the Agreement-in-Principle, is a commitment to define the relationship between the treaties and the overlapping sovereignties of the parties and explicitly recognize that contemporary governance agreements where treaties have been made will necessarily build upon a pre-existing foundation of reconciliation. [Note 39]

Moreover, as self-government agreements are between an Aboriginal signatory and the Crown, Aboriginal governments expressed difficulty in establishing a government to government relationship with the Crown. As stated by the Land Claims Agreement Coalition in 2006,

Recognition that the Crown in Right of Canada, not the Department of Indian and Affairs and Northern Development, is party to our land claims agreements and self-government agreements. [Note 40]

A Review of the Literature

The following section highlights key findings from a literature review that explores self-government over the past two decades from a First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives as well as Aboriginal women's perspectives. The focus of the literature review focused primarily on Aboriginal authors, most of whom are renowned scholars, lawyers, and/or politicians and generally recognized experts, both in their own communities and across Canada. Appendix A provides a bibliography of all documents reviewed for this section.

First Nation Perspective

The literature review reveals a number of First Nations perspectives on self-government and all begin with a general frustration that despite recent dialogue, negotiations, and policies, very little has actually been accomplished. The relationship continues to be unequal, with Canada possessing more power in negotiations while attitudes remain adversarial and inflexible instead of working towards mutually beneficial and community-specific partnerships. Canada continues to set the rules for engagement and expresses Canadian vision and self-interest, an approach that simply reinforces a colonial relationship maintained by INAC. Most authors express a need to decolonize political institutions (including the Indian Act, the reserve system, and the Assembly of First Nations) and some criticise the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoplesfor not doing enough to promote an entrenchment of self-government along similar lines as the Charlottetown Accord.

These mostly First Nations authors use history to confirm, from their point of view, the inherent Aboriginal right to self-government, which has been recognized in the past by the Royal Proclamation (1763) and various treaties (although some argue against an over-reliance on treaties since they exclude provincial governments today and are not internationally binding as Aboriginal nations are not states). Of course, different understandings of the Proclamation and treaties existed, understandings that evolve over time and shape our comprehension of the relationship today, as do diverse notions of concepts like sovereignty and ownership. Even the idea of self-government is contentious, as it implies recognition by a superior political power, while some authors prefer terms like nationhood and self-determination to better express the idea of 'right relationships' with people and the land. Additionally, from their point of view, the right to self-determination is guaranteed by international law and provinces cannot assume the Crown's fiduciary and constitutional obligations without Aboriginal consent.

All authors suggest big-picture ways in which to move forward, although they do not necessarily speak with one voice. While some argue that Aboriginal rights to self-determination are already entrenched in the Constitution thanks to various treaties (that express multiple pluralisms instead of a single Canadian sovereignty), others insist on a constitutional amendment to clearly outline the scope and protection of these rights (somewhat similar to the 'domestic dependent nation' status in the United States). Indeed, a better definition of what exactly self-government would entail and how it would be implemented is of major focus. Suggested reforms include:

- development of First Nations constitutions, legal codes, and procedural codes to develop the rule of law in communities;

- creation of Aboriginal Charters of Rights to be included in First Nations constitutions that would consider Aboriginal values and dispute-solving mechanisms, would protect legal and individual rights, and would preserve social, economic, and collective rights and responsibilities. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms need not be replaced, but these community-based charters would help contextualize Aboriginal values and responsibilities;

- abolition of INAC and the creation of a 'Ministry of First Nation—Crown Relations,' establishment of auditor and attorney generals, an ombudsman, a treaty commissioner, an Aboriginal and Treaty Rights tribunal and a national treaty policy (that the AFN has been promoting for years);

- respect for the spirit and intent of treaties and formation of various structures and mechanisms for treaty implementation in both the short and long-term (26 recommendations to achieve these steps in Saskatchewan listed in Arnot's work);

- development of a centralized education body, either on a national scale or based on specific language groups and/or cultures, to devise curricula, accredit teachers, and provide resources to fully realise the promise of Aboriginal-controlled education.

Emphatically, self-government should not simply reflect what many authors viewed as insubstantial municipal powers, but must include real powers, such as:

- personal and territorial jurisdiction, that stems from the Creator, to be applied to all residents on First Nation territories; Crown responsibility to demonstrate that Aboriginal jurisdiction in a particular area has been diminished (the 'full box' model);

- concurrent and exclusive powers for the expression of law on the territory;

- intergovernmental cooperation in the area of Aboriginal law (so that First Nations governments could 'rent' services out to another government as they develop their own capacity to deliver);

- administration of justice that may be carried out in collaboration with other orders of government; and

- financial support of self-government by levying taxes, borrowing money, and accessing transfer monies from other levels of government.

Finally, in order to realise self-government aspirations, First Nations need capacity building, a strong leadership, and good governance (that includes accountability and transparency, a constitution and rule of law, and a system of conflict resolution). Economic integration is key for self-sufficiency and a stable government and transparent business approaches will make communities attractive to investors. Democratic reform is also needed for success (which includes an improved band council structure and better election processes) in order to decolonize the mindset of dependency on the federal government and to empower Aboriginal communities to solve problems themselves. Finally, education is also closely linked to self-government and both the leadership and the communities must be trained in ways of governing and building businesses.

Métis Perspective

The Métis perspectives surveyed through the literature review highlight several key governance goals, including land security, local autonomy, and self-sufficiency. All authors stress the idea of evolution over time: contemporary governance is not meant to be rigid or final, but should be an evolving relationship between the Métis Nation and the Crown. Historical, cultural, and political issues of the Métis provide a context for self-government discussions, as does the examination of some current examples of successful Métis governance. Several themes appeared quite frequently: lack of a Métis land base and defined Métis membership; a constitutional obligation for the Crown to negotiate and actively protect and promote Métis rights instead of ignoring the issue; and a need to stop jurisdictional quarrels between the federal and provincial governments on who is responsible for the Métis.

The lack of a Métis land base remains of major concern for all authors. One article explores the Métis Settlements of Alberta, Canada's only legislated, land-based Métis Government, which might provide a model for other Métis or Aboriginal governments. Most other Métis governance structures to date have evolved off a land base and a significant urban population exists with their own developed organisations. Of course, the question of whom these organisations represent is also central and the Crown, several authors claim, has used this perceived lack of unity to deny constitutional rights on the basis of not knowing who or where the Métis actually are. The Supreme Court Decision Powley set out self-identification, ancestral connection, and community acceptance as criteria for determining membership, but one author criticises the centrality of race as a factor (ancestral connection) and protests the use of the Court—instead of the Métis themselves—to define a people.

The Powley decision also found that the Métis had constitutional rights similar to other Aboriginal peoples and the Crown has a duty to take positive action to negotiate and define them. While most authors view Section 35 of the Constitution as a guarantor of Métis and other Aboriginal rights, one author rejects what he considers a colonial framework and describes his offence at the apparent equivalence of the right to weave baskets to the right to good governance under s.35. Instead, international human rights doctrine is a better protector of Métis rights, he maintains.

Regardless of how exactly these rights are protected, all authors agree they must be negotiated, which the federal government has avoided doing until recently. Political participation of the Métis and other Aboriginal peoples in these negotiations is crucial for Canada to have a legitimate governing order. Of course, recognition of Métis rights can also be achieved in the courts—one author suggests simply exercising a right, like hunting, and then taking it to court when the province challenges it—but litigation is a costly and time-consuming process.

The authors suggest fewer concrete recommendations than other perspectives, likely due to the relatively new way of conceptualizing Métis rights and the recent reversal of the federal refusal to negotiate. Nevertheless, the recommendations touch on several issues:

- Métis membership: establish a Métis National Registry based on their own national definition of citizenship to define the scope of the Métis Nation and its homeland; establish a National Métis Citizenship and Elections Commission; have an independent Métis Nation Auditor General audit the registration system.

- Métis participation: establish a wide and transparent consultation process for the Métis Nation to discuss constitutional development and the following issues: roles and responsibilities of different levels of Métis governments; leadership selection issues and accountability; the Métis Nation's vision within Canadian federation.

- Métis governance: develop the Métis Nation's capabilities: look to successful past practices to expand longer-term capacity building and Métis-specific training initiatives; explore how to generate revenue for Métis governments.

- Intergovernmental relationships: address the jurisdictional impasse where both the federal and provincial governments refuse to take responsibility for the Métis, a policy that results in the denial of much needed programs and services (the Métis National Council has long claimed that the federal government has primary responsibility although one author argues the provincial and federal Crowns cannot be separated); expand effective relationships and review other intergovernmental models.

- Build upon the Canada-Métis Nation Framework Agreement to recognize the Métis Nation, their contributions to the Canadian federation, and to commit to a new nation-to-nation negotiation approach that includes the Métis in federal policies and in the development and implementation of future initiatives.

- Develop and pass a Canada-Métis Nation Relations Act to focus on a nation-to-nation relationship and the recognition of existing Métis Nation self-government institutions. Maintain transparent and accountable democratic governance, a Métis Nation citizenship registry, and the delivery of social and economic government services and programs paid for by the federal government, as occurs in other Aboriginal communities. Establish a Métis Nation Commission, similar to the Indian Claims Commission, to look at scrip, treaty, and compensation claims. Negotiate self-government based on Métis jurisdiction and law-making authority on a Métis land base, control over cultural and socio-economic activities, establishment of effective intergovernmental relations, and the Crown's legal duty to consult and accommodate.

Inuit Perspective

Since a number of self-government agreements for Inuit have already been—or are in the process of being—ratified, Inuit perspectives in this section concentrate less on the actual right to self-determination and focus instead on existing challenges, implementation, and policy priorities. Key areas of engagement include implementation and governance, sovereignty, global warming, economic development, funding, and education. Little focus is placed upon difficult social conditions in communities (the three biographies do recount past injustices), although issues of housing shortages and problems with drinking and violence are mentioned peripherally; a number of authors also insist that Inuit standards of living must be brought in line with the rest of the country. Similarly, the unique concerns of women do not feature prominently in these summaries (perhaps as only two authors are women), except for two biographies, which briefly mention the idea of creating a gender parity rule for Nunavut's legislature, a proposal that failed when put to the people. A number of authors concentrate on the past negotiation of various agreements and two contentious issues that continue to divide Inuit and Canadian authorities frequently appear: offshore jurisdiction and the extinguishment clause.

Moving on to the key areas of engagement, implementation continues to frustrate some authors as they feel the Canadian Government has not done enough to negotiate in the context of a renewed relationship and instead simply fulfil the bare minimum of obligations. That said, three new areas of Inuit self-government now exist or are close to being realised, with public governments in Nunavut and under negotiation in Nunavik, while Nunatsiavut is a regional government for Inuit only in Labrador. Of course, regardless of having a public government, the large Inuit majority in Nunavut allows—and will allow in Nunavik—them to shape policy and services in culturally and linguistically appropriate manners and integrate Inuit customs into laws. All systems are interesting hybrid, distinctly northern models; the newer regions of Nunavik and Nunatsiavut envision devolving jurisdictions, and, like Nunavut, high levels of community involvement. Most authors agree that Government should be decentralised so it can best respond to local concerns, but others fears this will create too large of a bureaucracy with redundant jobs. Education, housing, and health care remain of primary importance and several authors dislike having federal policy imposed upon them, like a new hunting license requirement or same-sex marriage legislation.

Sovereignty also played a major role in the literature, but it should be mentioned that all authors viewed Inuit sovereignty as being exercised within the Canadian state. That said, one author described sovereignty as beginning at home and stressed that Canada must ensure Inuit have the same standard of education, health care, infrastructure, and economic involvement as other Canadians. Inuit connections also extend beyond Canadian borders to Indigenous peoples in Greenland, Alaska, and Russia, all of whom possess the right to self-determination under international law and remain united under the Inuit Circumpolar Council. Regional institutions provide useful mechanisms for international cooperation and security and several initiatives should be explored, including Arctic-orientated military initiatives, a marine authority for transportation purposes and jurisdictional issues, responsible environmental management, sound civil administration, as well as common education and language priorities.

The authors highlighted that global warming is also opening up the Arctic to outside involvement; Inuit want to ensure they stay at the forefront of negotiations and that Canada and the international community value their consent, perspectives, and expertise as we create international partnerships in areas such as sustainable development, global environmental security, and other economic, military, health, and social initiatives. Similarly, discussion by the authors around the economy focused on renewable resources, the heritage of all Inuit, and a need for environmental monitoring (perhaps by the Arctic Rangers). Sustainability is also important, especially in light of climate change, and a permanent economy must focus on industries like fishing, windmills, and sun power instead of natural resource extraction with negative boom and bust cycles. Inuit must be onside for major development projects and, in the years since the creation of Nunavut, relations between Inuit and investors have improved, creating greater confidence in the Nunavut market and success in industries such as share holding in ships, the Qikiqtaaluk Corporation and an Inuit-owned airline. In terms of funding these new self-government entities, a number of authors call for a reduction in unnecessary costs and for the end of an unwieldy and costly system of applying for funding that is neither efficient, nor stable and hinders the development of long-term policy. Authors lament the large disparity in funding exists compared to First Nations communities, but Inuit governments are slowly establishing their own revenue streams through taxes, rent, royalties, etc.

Finally, protecting, preserving, and actively promoting language and culture remains of critical importance and multiple authors discuss the importance of teaching Inuktitut in schools and making it the primary language for Government. Just as the federal government supports English and French minorities in the rest of the country, Inuktitut must be supported in the North. Authors also call for a greater Inuit control of education: one author calls for establishment of an Inuit northern university while another desires an Inuit Knowledge Centre focused on research. Inuktitut-speaking teachers must be trained, Inuit curricula developed, and elders should be honoured for their knowledge and contributions.

Aboriginal Women Perspective

The literature revealed that Aboriginal women place much emphasis on the barriers to realising self-government, including the poor socio-economic conditions and extreme violence lived by many women, as well as discriminatory policies of the Indian Act, patriarchal values adopted by Aboriginal men that muzzle women, and the loss of language and culture in residential schools. Fundamental human rights must be addressed for self-government to be achieved, including the protection of the family, mother, and child, as well as the right to an adequate standard of living and to health. Unfortunately, mainstream remedies do little in poor, remote communities and authors instead call for gender-based, culturally appropriate approaches to health, social services, and governance structures. Historic origins of female involvement in governance also help guide the way and many women look to a resurgence of traditional values where women chose chiefs, helped govern by consensus, and passed down the language and culture.

Some authors see the Canadian Government as restricting Aboriginal self-government to fit under their own jurisdiction and law, and instead propose their own understanding of the term: the concept of "our way of life" or "our way of being," preferred by women at one forum, reflect indigenous languages, cultures, beliefs, ceremonies, and responsibilities, all of which are implied in the term self-government. A distinction between self-government and self-determination is also important for some with the former being a mid-point between assimilation and self-determination and reflected by agreements such as the Indian Act, which ultimately restricts indigenous independence.

Multiple authors use domestic and international laws, statutes, and covenants to insist upon an end to discrimination against indigenous women. The Canadian Constitutionprotects the inherent Aboriginal right to self-government and by consequence could affirm matriarchal governments and women's rights to political and cultural participation in Aboriginal societies. That said, some remain frustrated that litigation focuses on Aboriginal and Treaty rights, which often concentrate on traditionally male domains, such as hunting and fishing, usually ignoring female economies, such as gathering, agriculture, tanning skins, and sewing clothing. Furthermore, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms should protect the individual equality rights of women, which need not conflict with the collective rights of Aboriginal communities as both coexist in international law. Some authors argue for a hierarchy of rights where individual (political and civil) rights of women prevail over rights of Aboriginal collectivities, while others assert all rights exist within both the individual and the collective. Indeed, an Aboriginal woman cannot be removed from her culture and therefore her idea of rights differs dramatically from mainstream feminism: instead of demanding equality, for instance, indigenous women might desire a return to their traditional roles. One author emphasises that the entire concept of rights is wrong; the dialogue should instead focus on responsibilities in an Aboriginal context.

Much discussion revolved around Bill C-31, which continues to discriminate against women and their children with its second-generation cut-off rule, and the now-defunct Bill C-7, the First Nations Governance Act, which some authors saw as perpetuating discriminatory practices in violation of Canada's domestic and international promises. Similarly, some sexist Indian Act provisions include: continued status restriction even after the 1985 amendments; required identification of child's father and his status; denial of band membership to some women; prevention of non-members from living on reserves; and registration of homes and property in the male spouse's name. On the last note, the literature was also concerned with the issue of matrimonial real property and one article outlined the different concept of ownership found in Aboriginal customary law—opposed by the Indian Act—whereby, a custodial relationship exists between the land and the people who hold it in trust for future generations (for westerners, the emphasis is placed on land value, individual rights, and exclusive ownership).

Each author presented several recommendations to end discrimination against indigenous women and to move self-government forward. Key recommendations include:

- reform the Indian Act to eliminate all discriminatory provisions and policies; create a mechanism for dispute resolution and to remove leaders;

- fill legal gaps concerning matrimonial real property by consulting with elders and families; ensure equality in the division of assets after a divorce; prioritize solutions that serve the best interests of children;

- cut funding to band councils who refuse to provide services to re-instated women and children; re-evaluate membership laws and status declaration;

- fund a culturally relative gender-based analysis framework to be adopted by all levels of government involved in negotiations; focus on capacity-building for First Nation's women's groups;

- promote equal representation and participation for women in leadership roles at the negotiation and policy tables;

- guarantee equality rights set out in the Charterand the Constitution; possible establishment of an Aboriginal-specific charter or a national or regional human rights panel and a First Nations ombudsperson;

- adopt the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples;

- apply the recommendations of the RCAP, especially those related to family law;

- apply Aboriginal customary law but stress the principles of equality, fairness, and rights that may have been removed due to colonial and sexist practices;

- encourage good governance with accountable, transparent structures of decision-making, an inclusion of gender equality principles, an understanding of the past to better envision the future, a focus on the rule of law, the centrality of the land, and consensus-based decision making;

- define the roles and responsibilities of women, men, elders, youth, the family, and the clan; educate community members to their roles, responsibilities, and traditions to help them heal from a legacy of cultural genocide and abuse; and

- create a code of conduct for leaders, men, and women to help communities unite and stop fighting and discriminating against themselves; return power to the people; create independence and self-sufficiency with a land and resource base.

6. Evaluation Findings - Performance

The evaluation examined the achievement of results as indicated by the status of current self-government agreements and negotiations; a quantitative assessment of results based on an analysis of CWB Index for communities currently under self-government arrangements; and, qualitative assessment of results based on the case studies undertaken for this evaluation.

There are currently 18 self-government agreements in place as well as 91 tables negotiating self-government, 70 active tables and 21 inactive tables. Of the active tables, 50 tables are comprehensive land claims related with 20 tables as stand-alone/sectoral self-government negotiations. It is worthy of note that 51 percent (36 of the 70) of the active negotiating tables are within British Columbia as part of the BC Treaty Process. Data from the 2009-2010 Table Review process indicate that tables in negotiations, both active and inactive, represent approximately 350,000 Aboriginal people.

Empirical research shows that taking control of selected powers of self-government and capable governance institutions are indispensable tools to successful long-term community development in Aboriginal communities. The CWB analysis conducted indicates that Aboriginal communities currently with a self-government arrangement in place score higher on the CWB Index than First Nation communities (9 points higher) and Inuit communities (4 points higher), though remain lower than all Canadian communities (11 points lower).

Qualitatively, self-governing communities report that a major perceived benefit of self-government is a renewed sense of pride that they now have their own government as well as the right to elect their own governments and to make important decisions affecting their lives. Issues of scope and complexity of operating a new government, unrealistic expectations for what would be achieved under self-government, as well as access to financial resources were however identified as barriers to success.

6.1 Current Status of Self-Government Agreements and Negotiations

The following section provides information on the current status of self-government arrangements in place as well as the status of self-government negotiations underway. Claims related self-government agreements are defined as those negotiated in context with land claim agreements; stand-alone self-government agreements cover a wide range of subject areas but are not negotiated as part of a land claim; and sectoral self-government agreements include governance arrangements and may include additional jurisdiction such as education or child welfare.

Self-Government Agreements in Place

There are currently 18 self-government agreements in place. Eighty-three percent (15 of the 18 agreements) are associated with a comprehensive land claim. Also of note is that 61 percent (11 of the 18 agreements) are self-government agreements in the Yukon negotiated under the Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA). There are currently two stand alone agreements, both located in British Columbia – Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Agreement and Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement. In addition, the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act gives effect to nine Cree communities and one Naskapi community on local government commitments contained in the JBNQA and the NEQA.

Table 2: Self-Government Agreements in place by Province/Territory

| Province/ Territory | Year Agreement Signed | # of Communities | Registered Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claims Related Self-Government Agreements | ||||

| Nisga'a Final Agreement | BC | 2000 | 4 | 5,807 |

| Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement | BC | 2009 | 1 | 286 |

| Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement | NFLD | 2005 | 5 | 7,102 [Note 41] |

| Tilcho Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement | NWT | 2005 | 2 | 2,832 |

| Umbrella Final Agreement (1993) | ||||

| Vuntut Gwichin First Nation Self –Government Agreement | YT | 1995 | 1 | 524 |

| First Nation Nacho Nyak Dun Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1995 | 1 | 474 |

| Teslin Tlingit Council Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1995 | 1 | 573 |

| Champagne and Aishihik First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1995 | 1 | 813 |

| Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1998 | 1 | 609 |

| Selkirk First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1998 | 1 | 514 |

| Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in Self-Government Agreement | YT | 1998 | 1 | 695 |

| Ta'an Kwach'an Council Self-Government Agreement | YT | 2002 | 1 | 237 |

| Kluane First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 2004 | 1 | 143 |

| Kwanlin Dun First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 2005 | 1 | 964 |

| Carcross/Tagish First Nation Self-Government Agreement | YT | 2005 | 1 | 615 |

| Stand-Alone Self-Government Agreements | ||||

| Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Agreement | BC | 1986 | 1 | 1,267 |

| Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement | BC | 2004 | 1 | 691 |

| Sectoral Self-Government Agreement | ||||

| Mi'kmaq Education Agreement | NS | 1999 | 10 | 2,735 [Note 42] |

| Additional Self-Government Arrangements | ||||

| Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act | QC | 1984 | 10 | 17,260 |

Self-Government Negotiations

As of February 2011, INAC reports 91 negotiation tables with 70 active and 21 inactive. These tables represent 331 Aboriginal communities, including 302 First Nations, 20 Inuit communities and 9 James Bay Cree communities, and some Métis locals. Of the active tables, 50 tables are comprehensive land claims related with 20 tables as stand-alone/sectoral self-government negotiations. It is worthy of note that 51 percent (36 of the 70) of the active negotiating tables are within British Columbia as part of the BC Treaty Process. Data from the 2009-2010 Table Review process indicate that tables in negotiations, both active and inactive, represent approximately 350,000 Aboriginal people.

Table 3: Active Self-Government Negotiations by Province/Territory

| # of Active Tables | # of Communities | |

|---|---|---|

| Claims Related Self-Government Negotiations by Province | ||

| British Columbia | 36 | 82 |

| Ontario | 1 | 1 |

| Quebec | 4 | 12 |

| Atlantic | 4 | 32 |

| NWT | 5 | 16 |

| Total Claim Related Self-Government Negotiations | 50 | 143 |

| Stand Alone / Sectoral Self-Government Negotiations by Province | ||

| British Columbia | 0 | 0 |

| Alberta | 1 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 9 |

| Manitoba | 1 | 1 |

| Ontario | 3 | 91 |

| Quebec | 4 | 25 |

| Atlantic | 1 | 1 |

| Yukon | 1 | 1 |

| NWT | 7 | 13 |

| Total Active Stand Alone Self-Government Negotiations | 20 | 142 |

| Total Active Self-Government Negotiations | 70 | 285 |

6.2 Quantitative Assessment

Though no comparable study has been conducted in Canada, the emphasis on governance capacity is grounded in a growing body of evidence on the impact of good governance on the development of strong, healthy, and prosperous communities. The fundamental impact of good governance on socio-economic development objectives is supported by more than fifteen years of empirical research at Harvard University's Project on American Indian Economic Development. Their research consistently confirms that taking control of selected powers of self-government and capable governance intuitions are indispensable tools to successful long-term community development. [Note 43]

For the evaluation, an analysis of the CWB Index was conducted. CWB measures the quality of life of First Nations and Inuit communities in Canada relative to other communities. It uses Statistic Canada's Census and Population data to produce well-being scores for individual communities based on four indicators: Education, Labour Force, Income and Housing. It is important to note that the CWB Index data does not assess if the improvements of well-being in the self-governing communities are associated with the agreement themselves. This does not say that such association does not exist, but rather that these CWB measures do not demonstrate a direct relationship and that other factors may be more influential. In addition, communities are defined in terms of census subdivisions and these subdivisions at times do not accurately reflect the population under the self-government agreement. For example, non-Aboriginal people may be included with the census subdivision, as in the case for Tsawwassen First Nation. Moreover, CWB scores do not include members who do not reside in the community,

The CWB Analysis conducted indicates that overall Aboriginal communities currently with a self-government arrangement in place score higher on the CWB Index then First Nation, and Inuit communities though lower than all Canadian communities.

Table 4: CWB 2006 Average Scores

| 2006 Average CWB Score | Differential | |

|---|---|---|

| All Canadian communities | 77 | +11 |

| Self-government communities [Note 44] | 66 | - |

| Inuit communities | 62 | - 4 |

| First Nation communities | 57 | - 9 |

The following section provides details of the CWB data including scores by individual self-governing communities. [Note 45]

Table 5: CWB Index Data from 1981 to 2006 [Note 46]

| Province/ Territory | Year Agreement Signed | CWB Score 1981 | CWB Score 1991 | CWB Score 1996 | CWB Score 2001 | CWB Score 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claims Related Self-Government Agreements | |||||||

| Nisga'a | BC | 2000 | 51 | 57 | 61 | 66 | 65 |

| Tsawwassen | BC | 2009 | - | 81 | 78 | 81 | 89 |

| Labrador Inuit | NFLD | 2005 | 51 | 52 | 57 | 62 | 66 |

| Tilcho | NWT | 2005 | - | - | 51 | 59 | 60 |

| Vuntut Gwichin | YT | 1995 | - | - | 64 | 70 | 71 |

| Nacho Nyak Dun | YT | 1995 | - | - | 73 | 73 | 79 |

| Teslin Tlingit Council | YT | 1995 | - | 57 | 64 | 66 | 72 |

| Champagne and Aishihik | YT | 1995 | - | - | 76 | 79 | 80 |

| Little Salmon / Carmacks | YT | 1998 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Selkirk | YT | 1998 | - | - | - | 72 | 71 |

| Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in | YT | 1998 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kluane | YT | 2004 | - | - | 74 | 78 | |

| Kwanlin Dun | YT | 2005 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Carcross/Tagish | YT | 2005 | - | 53 | 67 | 71 | 74 |

| Stand-Alone Self-Government Agreements | |||||||

| Sechelt | BC | 1986 | 53 | 64 | 67 | 63 | 70 |

| Westbank | BC | 2004 | 69 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 78 |

| Sectoral Self-government Agreements | |||||||

| Mi'kmaq Education Agreement | NS | 1999 | 48 | 51 | 58 | 60 | 63 |

| Acts | |||||||

| Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act | QC | 1984 | 47 | 51 | 60 | 60 | 64 |

| First Nations and Inuit Communities and Other Canadian Communities | |||||||

| First Nation communities | - | - | 47 | 51 | 55 | 57 | 57 |

| Inuit communities | - | - | 48 | 57 | 60 | 61 | 62 |

| Other Canadian Communities | - | - | 67 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 77 |

| Self-governing Aboriginal communities | - | - | - | - | - | - | 66 |

The following provides details of the CWB analysis by self-governing community.

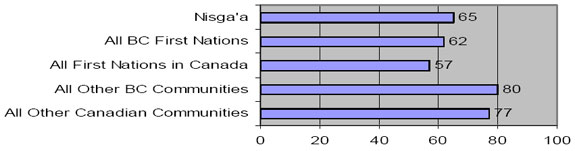

Nisga'a : Average CWB Scores for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Nisga'a as compared to all BC First Nations, all First Nations in Canada, all other BC communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Nisga'a: 65/100

- All BC First Nations: 62/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other BC Communities: 80/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Nisga'a scored

- 3 points higher than all BC First Nations;

- 8 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 15 points lower than all other BC communities; and

- 12 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nisga'a | 57 | 48 | 75 | 70 |

| All BC First Nations | 59 | 38 | 76 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other BC Communities | 85 | 58 | 94 | 85 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

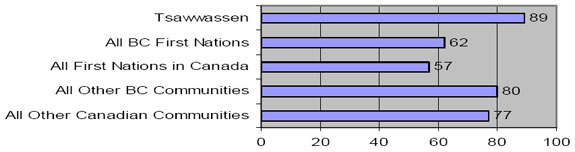

Tsawwassen: Average CWB Scores for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Tsawwassen as compared to all BC First Nations, all First Nations in Canada, all other BC communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Tsawwassen: 89/100

- All BC First Nations: 62/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other BC Communities: 80/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Tsawwassen scored:

- 27 points higher than all BC First Nations;

- 32 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 8 points higher than all other BC communities; and

- 12 points higher than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsawwassen | 100 | 70 | 96 | 91 |

| All BC First Nations | 59 | 38 | 76 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other BC Communities | 85 | 58 | 94 | 85 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

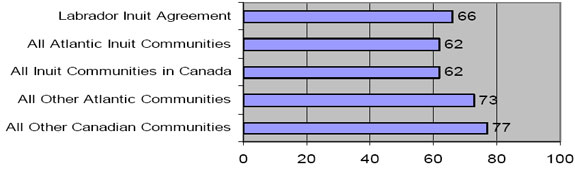

Labrador Inuit Agreement: Average CWB Scores for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Labrador Inuit Agreement as compared to all Atlantic Inuit communities, all Inuit communities in Canada, all other Atlantic communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Labrador Inuit Agreement: 66/100

- All Atlantic Communities in Canada: 62/100

- All Inuit Communities in Canada: 62/100

- All Other Atlantic Communities: 73/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 the Labrador Inuit Agreement scored:

- 4 points higher than all Atlantic Inuit Communities;

- 4 points higher than all Inuit communities in Canada;

- 7 points lower than all other Atlantic communities; and

- 11 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labrador Inuit Agreement | 70 | 42 | 78 | 68 |

| All Atlantic Inuit Communities | 71 | 43 | 81 | 68 |

| All Atlantic First Nations Communities | 56 | 46 | 81 | 73 |

| All Other Atlantic Communities | 76 | 46 | 94 | 76 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

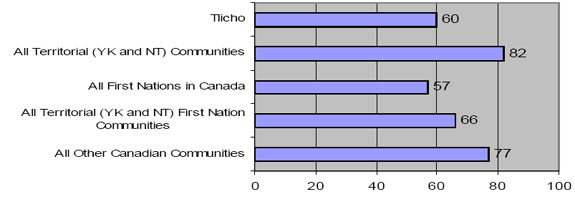

Tlicho: Average CWB Scores for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Tlicho as compared to all Territorial (YK and NT) communities, all First Nations in Canada, all Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Tlicho: 60/100

- All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities in Canada: 82/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation Communities: 66/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Tlicho scored:

- 20 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 3 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 6 points lower than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 17 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tlicho | 68 | 28 | 64 | 73 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nations | 75 | 36 | 76 | 78 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities | 91 | 59 | 88 | 89 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

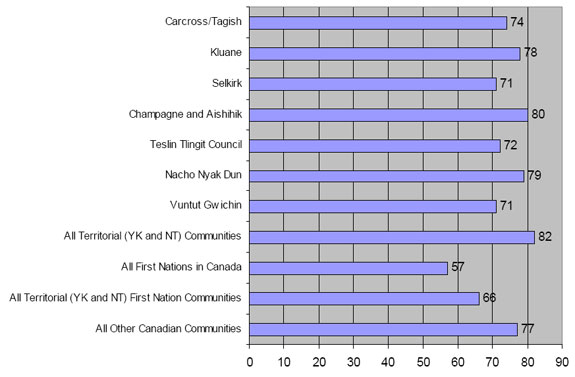

Yukon First Nations: Average CWB Scores for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for seven self-governing First Nations in the Yukon (for which a CWB score was available) as compared to all Territorial (YK and NT) communities, all First Nations in Canada, all Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Carcross/Tagish: 74

- Kluane: 78

- Selkirk: 71

- Champagne and Aishihik: 80

- Teslin Tlingit Council: 72

- Nacho Nyak Dun: 79

- Vuntut Gwichin: 71

- All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities in Canada: 82

- All First Nations in Canada: 57

- All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation Communities: 66

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Carcross/Tagish scored:

- 8 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 17 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 8 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 3 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Kluane scored:

- 4 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 21 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 12 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 1 point higher than all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Selkirk scored:

- 11 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 14 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 5 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 6 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Champagne and Aishihik scored:

- 2 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 23 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 14 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 3 points higher than all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Teslin Tlingit Council scored:

- 10 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 15 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 6 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- The same as all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Nacho Nyak Dun scored:

- 3 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 22 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 13 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 2 points higher than all other Canadian communities.

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Vuntut Gwitchin scored:

- 11 points lower than all Territorial (YK and NT) Communities;

- 14 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 5 points higher than all other Territorial (YK and NT) First Nation communities; and

- 6 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vuntut Gwitchin | 83 | 39 | 80 | 84 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nations | 75 | 36 | 76 | 78 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities | 91 | 59 | 88 | 89 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

| Champagne and Aishihik | 86 | 58 | 89 | 87 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nations | 75 | 36 | 76 | 78 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities | 91 | 59 | 88 | 89 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

| Selkirk | 80 | 43 | 78 | 82 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nations | 75 | 36 | 76 | 78 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities | 91 | 59 | 88 | 89 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

| Carcross/Tagish | 81 | 49 | 86 | 78 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) First Nations | 75 | 36 | 76 | 78 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Territorial (YK and NT) Communities | 91 | 59 | 88 | 89 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

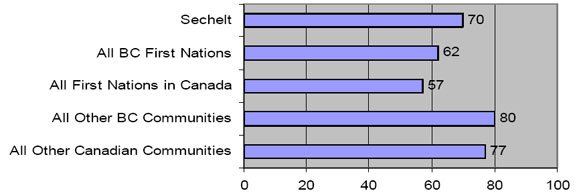

Sechelt: Average CWB Score for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Sechelt as compared to all BC First Nations, all First Nations in Canada, all other BC communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Sechelt: 70/100

- All BC First Nations: 62/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other BC Communities: 80/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Sechelt scored:

- 8 points higher than all BC First Nations;

- 13 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 10 points lower than all other BC communities; and

- 7 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sechelt | 69 | 49 | 82 | 79 |

| All BC First Nations | 59 | 38 | 76 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other BC Communities | 85 | 58 | 94 | 85 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

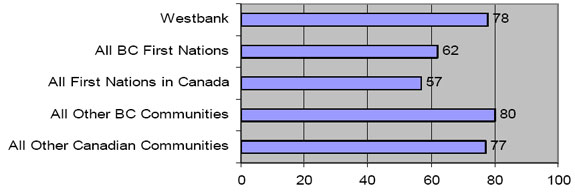

Westbank: Average CWB Score for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for Westbank as compared to all BC First Nations, all First Nations in Canada, all other BC communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Westbank: 78/100

- All BC First Nations: 62/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other BC Communities: 80/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 Westbank scored:

- 16 points higher than all BC First Nations;

- 21 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 2 points lower than all other BC communities; and

- 1 point higher than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Westbank | 78 | 53 | 94 | 84 |

| All BC First Nations | 59 | 38 | 76 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other BC Communities | 85 | 58 | 94 | 85 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

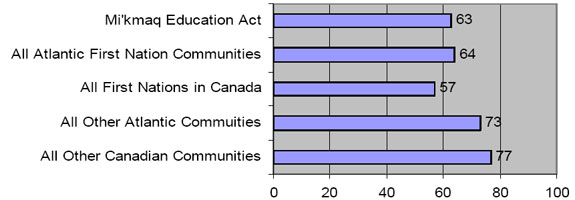

Mi'kmaq Education Act: Average Score for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for the Mi'kmaq Education Act as compared to all Atlantic First Nation communities, all First Nations in Canada, all other Atlantic communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Mi'kmaq Education Act: 63/100

- All Atlantic First Nation Communities: 64/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other Atlantic Communities: 73/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 the Mi'kmaq Education Act scored:

- 1 point lower than all Atlantic First Nation communities;

- 6 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 10 points lower than all other Atlantic communities; and

- 14 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mi'kmaq Education Act | 49 | 47 | 77 | 70 |

| All Atlantic First Nation Communities | 56 | 46 | 81 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other Atlantic Communities | 76 | 46 | 94 | 76 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

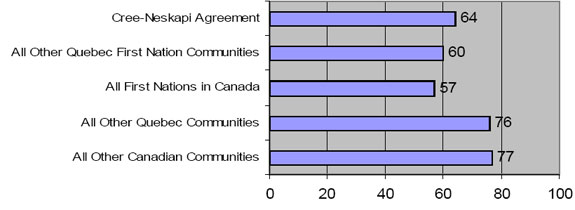

Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act: Average Score for 2006

The table above illustrates the CWB Scores for the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act as compared to all other Quebec First Nation communities, all First Nations in Canada, all other Quebec communities and all other Canadian communities for census year 2006.

- Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act: 64/100

- All Other Quebec First Nation Communities: 60/100

- All First Nations in Canada: 57/100

- All Other Quebec Communities: 76/100

- All Other Canadian Communities: 77/100

The table demonstrates that in 2006 the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act scored:

- 4 points higher than all other Quebec First Nation communities;

- 7 points higher than all First Nations in Canada;

- 12 points lower than all other Quebec communities; and

- 13 points lower than all other Canadian communities.

| 2006 Component CWB Scores | Income | Education | Housing | Labour Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cree-Neskapi (of Quebec) Act | 69 | 36 | 69 | 80 |

| All Quebec First Nation Communities | 60 | 32 | 74 | 73 |

| All First Nations in Canada | 55 | 34 | 70 | 71 |

| All Other Quebec Communities | 79 | 48 | 94 | 83 |

| All Other Canadian Communities | 80 | 49 | 94 | 84 |

6.3 Qualitative Assessment

Key qualitative findings were derived from the case studies with three participating Aboriginal communities. The following highlights their overall perspectives regarding the achievements and challenges of self-government in their communities. [Note 47]

- A major perceived benefit of self-government is a renewed sense of pride that self-governing Aboriginal groups now have their own government, the right to elect their own governments, and to make important decisions affecting their lives.

- Self-government agreements, both comprehensive and sectoral, are viewed as being sufficiently broad in terms of what is covered in the agreements to allow them to manage their own affairs. However, while the structure of the agreements is sufficient, the human and financial resources required to fully realize the potential of the agreements are not currently available.

- The manner in which federal government funding is calculated under the self-government agreements is viewed as prejudicial to successful implementation of self-government. Amounts allocated for functions taken over by the new Aboriginal governments are seen as inadequate partly because they were inadequate under the Indian Act already, and partly because they don't adequately factor in the costs of transition. Transfers for government operations are similarly viewed as inadequate because the costs of establishing a new government are higher than the funding anticipates, and because substantial funding targeted for government operations are used to cover the costs of programs and services for basic community and individual needs that are themselves not adequately funded.

- While access to financial resources was widely viewed as a barrier to success, some respondents pointed to the benefits of greater flexibility under the agreements, that allows funds to be moved more freely among programs and between fiscal years than was the case under the Indian Act. This flexibility is said to have fostered better long-term planning and more scope for innovation in service delivery. In one case this flexibility was said to have even helped attract and retain local residents who had been educated (and in some cases employed) outside the community.

- Aboriginal governments are realizing the scope and complexity of operating a new government, and the need for educated and experienced people to lead the process and fill government positions. The plan in all cases is to focus on education and training to help fill public service positions with community members. However, Aboriginal governments reportedly face difficult challenges in recruiting and retaining educated community members to take public service positions, against higher-paying positions in other levels of government and the private sector.

- Expectations for what would be achieved under self-government were described as unrealistic for both community leaders and members. In many cases, community members thought that the agreements would bring an early influx of money, jobs and improved services. Aboriginal governments recognize that change resulting from self-government will take place incrementally, over several generations. They also recognize that this change is dependent on improvements in education outcomes as well as labour and economic development opportunities.

Governance and Intergovernmental Relationships

Governance

- Interviews with Aboriginal Government officials highlight the fact that that success to date has been largely in establishing governance structures, procedures and associated legislation, and in setting priorities and preparing to take on new authorities and jurisdictions. This work surprised most respondents in its complexity and in the time it has taken to set the foundation for governance under the self-government agreements.

- Interview participants recognized that there is a degree of frustration and disappointment among community members at the slow pace of change in the communities. There was an expectation, reportedly widely shared by residents and shared to a lesser degree by community leaders, that land claim agreements and self-government (which are often viewed together by community members) would transform the lives of community members through the creation of employment, the influx of money from land claim agreement settlements, and the new ability of their own governments to make decisions in key areas. However, respondents remain cautiously optimistic that these expectations will be realized over time.

- To date, the work of Aboriginal governments has focused primarily on developing the structures, procedures and legislation that the new governments require to operate. Government respondents noted that citizens have expressed concern that their governments are "working behind closed doors". While government respondents recognized this concern, they described the extent of openness and public consultation their government has undertaken in an effort to be as transparent as possible and to engage residents in governance. The respondents believed that the concerns are largely borne out of the limited direct benefits being experienced to date in areas such as education, employment and housing.

- Public participation in governance was described as very positive compared to before self-government was in effect. More community members are running for government positions, and voter turnout has reportedly increased (up to about 75 percent in Nunatsiavut, for example, as compared to well under 50 percent before self-government). In Labrador women are reportedly more politically active as well. Respondents there noted that before self-government, women were active in community gatherings but less active in formal governance. Since self-government, many women are running for office and assuming public service positions.

Intergovernmental Relationships

Self-government establishes government-to-government relationships where they did not exist previously. Previous studies have suggested that Aboriginal groups had greater expectations of a new partnership with the federal government than what they have realized to date. [Note 48] The self-government interviews addressed this issue, and found the following:

- In program areas in which communities are not equipped or do not have sufficient resources to assume control as provided for in the agreements, the nature of the relationship with the federal government is perceived as being the same as prior to the agreements (i.e. "Band Council to federal bureaucracy" rather than government-to- government).

- Interview participants expressed concern that there is no clear location in the federal government with which to establish a government-to-government relationship. Points of contact are primarily INAC representatives on implementation committees and officials responsible for federal programs for which the communities continue to apply to for funding as they did prior to self-government.

- Interview participants in Yukon and Labrador noted the barriers to implementing self-government that result from INAC's perceived limited influence over line departments and government agencies. In particular, Yukon respondents pointed to a recent example in which INAC and local government representatives spent considerable time and effort working together to identify changes that were needed, but little change resulted due to a lack of support from other departments/agencies.

- Relationships with implementation committee representatives are described as cordial and professional, but focused on technical aspects of fulfilling the agreements, as opposed to developing a new government-to-government relationship.

- There is a perception among Aboriginal Government leaders that there is little concerted effort among line departments within the federal system to educate staff about the agreements. They said that Aboriginal governments therefore consistently have to "re-educate" their federal counterparts about the agreements and about community concerns related to implementation.