Archived - Evaluation Update of the Climate Change Adaptation Program: Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 2011

Project Number: 1570-7/10006

PDF Version (264 Kb, 51 Pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Evaluation findings - Summary of the 2009 implementation evaluation

- 4. Performance - Results

- 5. Results - Economy, efficiency & cost-effectiveness

- 6. Summary of Findings, Conclusions & Recommendations

- Annex A: Key informant interview selection criteria

List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

Introduction

Program profile & purpose of evaluation

This report presents the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the Update Evaluation of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program, which forms part of Canada's Clean Air Agenda (CAA), Over the past three fiscal years (2008-09 to 2010-11), this Program has provided over $10 million to Aboriginal and northern communities and other organizations working at the local-level to assess and identify climate change risks and develop and implement projects and plans that increase community-level capacity to address climate change impacts.

The present evaluation was conducted as a follow-up to a 2009 implementation evaluation which focused on relevance of adaptation programming and the design and delivery of the Program. In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat's (TBS) directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009), the present evaluation completes the evaluation requirement for this program through an examination of the Program's achievement of outcomes, and its economy, efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Scope and timing of evaluation

The evaluation focuses on program performance from September 1, 2008 (the date when projects first received funding) to October, 2010 (the start of the evaluation). Following TBS requirements, the evaluation scope includes both $10.2 million in contributions funding and $3.8 million in related administrative departmental spending. INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch and the consulting firm Prairie Research Associates Inc. jointly conducted the evaluation between October 2010 and January 2011.

Methodology

Building on the relevance and design and delivery findings of the 2009 implementation evaluation, the evaluation posed the following questions: 1) What progress has the Program made toward achieving its intended outcomes? 2) Have there been unintended outcomes as a result of the Program? 3) How efficient and cost-effective is the Program? 4) How does the relationship between the Program and its partners contribute to cost-effectiveness? and 5) Are there more cost-effective and efficient means of achieving the objectives of the Program? A matrix of indicators and data sources for each evaluation question guided all stages of the evaluation. Further quality control was ensured through internal peer review and review f the methodology report, preliminary findings PowerPoint presentation and draft report by program representatives.

The evaluation questions were addressed with information drawn from the following data collection tasks: document review; administrative and financial data review; file review; and key informant interviews. Interviews were conducted with 24 respondents representing program staff and management; project proponents; other federal government departments with related climate change programs and territorial and provincial climate change directors and coordinators.

The evaluation encountered a number of limitations. An absence of baseline data made it difficult to determine the general capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to address climate change issues and the extent to which the program has raised awareness. Information on the value of the program and communities' use of climate change information in planning and decision-making processes was not available in project final reports and the accuracy of information gathered from project leaders and INAC staff was not verified with community members. Most importantly, the timing of the evaluation in the final year of the three year program meant that the evaluation must focus on the Program's progress toward outcomes, rather than arriving at firm conclusions concerning the extent to which the program has achieved its intermediate and long-term outcomes. Mitigating strategies were put in place for each of the identified limitations.

Key findings

Continued need / Responsiveness to need

There is continued need for the Program. There is a need to continue to build capacity and work with communities that have not begun to engage in adaptation planning. It appears that the Program may not have reached communities in greatest need of support or those requiring immediate support. Possible explanations are that communities in need of support may not have the capacity to participate in the Program; without a formal call for proposals, the Program may not have identified communities in greatest need and, finally, given its short duration, the Program targeted communities that were ready to begin working on adaptation projects.

Outcomes –Performance

Collaboration

The Program worked to strengthen its relationships with other federal departments and territorial governments. It fostered the development of relationships between scientists, consultants, experts, and communities. Despite these efforts, some projects have experienced challenges. Several have found it difficult to achieve long-term commitments and shared vision. Additionally, there is significant staff-turnover at the community and territorial levels that can hinder relationship building. Finally, some community members are experiencing consultation fatigue and are reluctant to participate in climate change discussions.

Access/availability to information

The Program has contributed to increased availability of climate change information and expertise. Almost half of the funded projects focused on assessment of climate change risks and impacts. To a lesser extent, projects facilitated information-sharing and the development of adaptation tools. Nonetheless, there is a need to increase community-level coordination of adaptation work and sharing of project results. There is also a need to continue the work underway in participating communities and to engage new communities in adaption projects.

Increased ability to assess climate change risks

Most of the funded projects identified climate change risks and, in large part, this process directly involved community members. These projects identified a vast range of climate risks from permafrost degradation to flooding to reduced ice thickness. In addition, projects identified a number of specific impacts to communities associated with these risks such as infrastructure vulnerability, loss of traditional land-use practices and cultural identity and food security issues. Although many communities in a geographical area face the same core set of risks, the magnitude of risk varies across communities. Few communities have recognized opportunities from climate change.

Another noteworthy finding in relation to the Program's role in increasing communities' ability to assess risks was that roughly one quarter of funded projects involved the scientific assessment of risks including those to water, permafrost and seal-level rise. These projects provide vital data for planning activities and climate change trend analysis.

Capacity

The Program is increasing awareness of climate change within participating communities. However, there is a continued need to raise awareness of climate change impacts as some community members question whether the changes experienced simply reflect unusually variable weather conditions. Additionally, there is a need for repeat messaging.

The Program has begun to increase the capacity of participating communities to adapt to climate change. In part, this is the result of increased awareness of risks and possible adaptation strategies. It also results from increases in communities' ability to understand, support, and benefit from research, particularly through projects that actively engage community members. More generally, the Program's close relationship with territorial governments has increased capacity at that level. Nonetheless, many communities lack the financial and human resources required to engage in adaptation planning, pointing to the need for continued work in this area.

The evaluation found some evidence that communities are developing adaption plans. By the end of the Program, adaptation plans will be in place for 15 communities. The evaluation found mixed evidence relating to the usefulness of these plans, though it should be noted that it difficult to draw conclusions on this point given the fact that plans have either only recently been completed or are still underway. On the whole, plans that apply a community-based approach and successfully integrate climate change data appear more likely to be incorporated into community-level decision-making.

Unintended outcome: Actions to reduce vulnerability

Some projects have resulted in actions taken to reduce vulnerability to climate change. Few communities have begun to implement projects. Implementation of projects is one step ahead of the long-term expected outcome of the Program.

Results – Economy, Efficiency & cost- effectiveness

The Program complements other CAA Adaptation Theme Programs, the National Roundtable on the Environment and Economy work on Climate Change Adaptation, and the Public Infrastructure Engineering Vulnerability Committee (PIEVC) national engineering vulnerability assessment. To a limited extent, evidence suggests that the Government of Canada's program for International Polar Year duplicates the Program as these two programs fund similar adaptation projects.

Successes

The Program provided 75 percent of its available funding to projects and planned and actual expenditures were closely aligned. The Program funded 86 projects, thereby exceeding its goal by 26 projects. The Program attempted to maximize its efficiency by coordinating administrative activities with INAC's ecoENERGY Program, having regional offices set-up funding agreements, travelling to more than one community during trips to the North and co-funding projects where possible.

The Program demonstrated cost-effectiveness by leveraging $5.2 million funding and in-kind resources from other sources. However, little sharing of information resources across and between communities occurred and few funded projects are replicable because they are location-specific

Areas for improvement

According to key informants, several opportunities to improve the economy and efficiency of the Program exist. Information and resources including tools and manuals could be more effectively shared across communities. INAC headquarters' relationship with regional offices could be strengthened to improve the Program's understanding of regional issues. Program-related communications could be increased to raise awareness about the Program. Project funds could be distributed to projects in a more timely fashion (depending on constraints involved with INAC financial processes). Program and project duration could be expanded to limit the time involved in applying for funding. Proposals could be solicited through a formal call to enable the Program to better target specific projects. Finally, a joint funding application could be established with other programs and departments.

Alternative approaches

The cross-jurisdictional review revealed that other jurisdictions are taking a number of different approaches to adaptation support. These include incorporating adaptation into existing programming channels (e.g. infrastructure funding); providing training to planners; developing toolkits and manuals for planning exercises; providing information through online databases and funding macro studies on climate change adaptation. Additionally, some key informants felt that adaptation planning could potentially be integrated into other planning processes given the availability of adequate modeling, climate change scenarios and other climate change assessment information.

Conclusion

The Program appears to be on-track to achieve its intended immediate and intermediate outcomes. The Program has fostered collaboration with other federal departments involved in the Adaptation Theme of the CAA, territorial governments and a range of others on adaptation projects. It has increased participating communities' awareness of climate change risks and impacts and increased the availability of climate change adaptation information and tools. It has supported assessment of climate risks and development of some adaptation plans.

Despite the Program's successes, more time is needed to fully realize outcomes and improvements can be made to help achieve future success. Many communities lack capacity to participate in adaptation projects. Few communities have begun to implement projects to reduce their vulnerability to climate change. Improvements can be made to the Program to better target communities in need as well as those with existing capacity. The benefits of funded projects can be maximized through more efficient and effective processes.

Recommendations

The evaluation offers the following recommendations to improve the success, efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the Program:

- To increase its ability to identify and reach communities in need and better align efforts with regional strategies,INACshould:

- Continue to strengthen relationships with INAC regional offices.

- Continue to seek opportunities to work with provincial and territorial climate change offices.

- Continue to strengthen relationships with INAC regional offices.

- To increase communities' awareness of funding opportunities, secure a broader range of applicants and better target funding,INACshould:

- Continue to proactively inform individual communities of funding opportunities.

- Solicit applications through a formal call for proposals.

- Continue to proactively inform individual communities of funding opportunities.

- To provide Aboriginal and northern communities with one-window access to funding opportunities, INAC should explore opportunities for coordinating its call for proposals and application processes with other similar programs.

- To take advantage of the climate change adaptation research that has been completed, INAC should find additional ways to share results across communities through, for example, integrating data into the Government of Canada's International Polar Year database.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation Update of the Climate Change Adaptation Program: Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program

Project #: 1570-7/10006

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) | Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. To increase its ability to identify and reach communities in need and better align efforts with regional strategies,INACshould:

a. Continue to strengthen relationships with INAC Regional Offices. b. Continue to seek opportunities to work with provincial and territorial climate change offices. |

We _do____ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Sheila Gariépy, Director, Environment and Renewable Resources / Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: Upon program initiation |

| Future programming (subject to renewal) will formalize information exchange processes and seek opportunities to work more closely with INAC Regional Offices and other jurisdictions | Completion: March 31, 2012 |

||

| 2. To increase communities' awareness of funding opportunities, secure a broader range of applicants and better target funding, INAC should: a. Continue to proactively inform individual communities of funding opportunities. b. Solicit applications through a formal call for proposals. |

We _do____ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Sheila Gariépy, Director, Environment and Renewable Resources / Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: Upon program initiation |

| Future programming (subject to renewal) will

a) develop a communications strategy to target and inform communities of funding opportunities; b) solicit applications through a formal call for proposals |

Completion: March 31, 2012 |

||

| 3. To provide Aboriginal and northern communities with one-window access to funding opportunities, INAC should explore opportunities for coordinating its call for proposals and application processes with other similar programs. | We _do____ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Sheila Gariépy, Director, Environment and Renewable Resources / Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: Upon program initiation |

| Future programming (subject to renewal) will work closely with federal departments delivering complementary programs to more closely align the call for proposal and proposal application processes. | Completion: March 31, 2012 |

||

| 4. To take advantage of the climate change adaptation research that has been completed, INAC should find additional ways to share results across communities through, for example, integrating data into the Government of Canada's International Polar Year database. | We _do____ concur. (do, do not, partially) |

Sheila Gariépy, Director, Environment and Renewable Resources / Northern Affairs Organization | Start Date: Upon program initiation |

| Future programming (subject to renewal) will work closely with communities to facilitate information exchange | Completion: March 31, 2012 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed by

Name: Judith Moe

Position: Acting Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed by

Name: Janet King

Position: Assistant Deputy Minister, Northern Affairs Organization

MRAP was signed by A/Director of EPMRB and Sr. ADM/ Regional Operations Sector on February 15, 2011

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation Update of the Climate Change Adaptation Program: Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on February 22, 2011.

1. Introduction

This report provides the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of the Update Evaluation of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program (the Program), which forms part of the Adaptation Theme of the Clean Air Agenda (CAA) of the Government of Canada.

The present evaluation was conducted as a follow-up to a 2009 implementation evaluation which focused on relevance of adaptation programming and the design and delivery of the Program. [Note 1] In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat's (TBS) directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009), the evaluation update examines the Program's achievement of outcomes, and its economy, efficiency and cost-effectiveness, thereby completing the evaluation requirement for the Program.

The objectives of the Program are to assist Aboriginal and northern communities to assess and identify climate change risks and develop and implement projects and plans that increase community-level capacity to address climate change impacts. [Note 2] To achieve these objectives, this three-year (2008–09 to 2010–11), $14 million Program awards contributions to territorial governments, non-governmental organizations, Aboriginal organizations, related federal departments such as Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), communities and other northern institutions, and associations to help northern and Aboriginal communities understand the impacts of climate change and take steps to adapt or respond to anticipated changes.

1.1 Scope and timing of evaluation

The evaluation focuses on program performance from September 1, 2008 (the date when projects first received funding) to October, 2010 (the start of the evaluation). Following TBS requirements, the evaluation scope includes both $10.2 million in contributions funding and $3.8 million in related administrative departmental spending. INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) and the consulting firm Prairie Research Associates Inc. jointly conducted the evaluation between October 2010 and January 2011.

1.2 Outline of the report

The remainder of Section 1 describes the Program. Section 2 defines the evaluation scope and outlines the evaluation methodology. Section 3 summarizes the findings of the 2009 implementation evaluation. Section 4 presents the findings for program performance and Section 5 presents the findings of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Section 6 concludes the report and offers recommendations.

1.3 Program profile

This section provides a brief overview of the Program including the Program background, objectives and expected outcomes, resources and management structure. Additional information about the Program is available in the 2009 implementation evaluation report.

1.3.1 Background

Through an extensive literature review, the 2009 implementation evaluation found evidence, from both scientific and local observations, that climate change poses significant risks to Canada's northern regions. Conversely, it is expected that climate change will present opportunities for resource extraction and other economic development. Research suggests that climate change will have substantial effects on a number of areas including the environment and ecosystems of the North; Indigenous traditional lifestyles and resource sustainability, development and conservation. [Note 3]

In response to climate change, many jurisdictions are combining mitigation measures (i.e. greenhouse gas emission reduction) with adaptation strategies. While mitigation plays an important role in slowing and preventing climate change, it is clear that climate change impacts will be felt in many regions of the world, particularly high risk areas such as Canada's arctic. Adaptation efforts similar to those supported through INAC's climate change program help communities apply a proactive approach to preparing for climate change.

1.3.2 Objectives and expected outcomes

The objectives of the Program are to assist Northerners to:

- "Assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change; and

- Develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans to increase the capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to address the impacts of a changing climate." [Note 4]

The Program does not fund the implementation of adaptation planning. Eligible projects include those that:

- "Assess the risks and vulnerabilities to Aboriginal and northern communities related to the impacts of climate change;

- Support the preparation of action plans focusing on economic, social, cultural, environmental, and security issues;

- Address major issues related to climate change, such as:

- Emergency management and food security,

- Integration of climate change impact considerations into land use and community planning processes,

- Vulnerability of community infrastructure and of industrial and resource sectors,

- Development of adaptation management options, and

- Taking into account long-term changes to major project lifecycles; and

- Emergency management and food security,

- Result in specific tangible adaptation measures to address critical community issues such as storm surges and coastal erosion." [Note 5]

The Program's intended outcomes are listed in Table 1.

| Timing | Intended outcomes |

|---|---|

| Long-term outcome |

|

| Intermediate outcomes |

|

| Immediate outcomes |

|

Source: INAC (2008). Climate Change Adaptation for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Initiative. Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk Based Audit Framework

1.3.3 Program resources

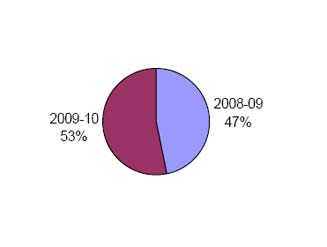

TBS allocated the Program $14 million in funding over the three-year period 2008–09 to 2010‑11. As Table 2 below shows, the Program's planned expenditures for each fiscal year were: $4.7 million in 2008‑09, $4.8 million in 2009–2010, and $4.5 million in 2010–2011. Section 5 compares planned and actual expenditures. Due to the level of work required to develop and launch the Program in its first year of funding, as well as the need to build community awareness of the Program (refer to Section 4.1), program expenditures for the first two years of the Program were $1.9 million less than anticipated. Consequently, the Program re-profiled $600,000 to 2009–10 and $1,550,000 to 2010–11.

Table 2 represents the Program's planned expenditures for 2008-09 to 2010-11 and Table 3 shows actual expenditures (TB and A-base) in the first two years of the Program and planned expenditures for the final year. Planned and actual expenditures are closely aligned.

| Requirement | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ($ '000) | ||||

| Salaries | $454 | $454 | $359 | $1,456 |

| Operating Expenses | $996 | $596 | $522 | $1,862 |

| Employee Benefits Program | $91 | $91 | $72 | $292 |

| Transfer Payments – Grants | - | - | - | - |

| Transfer Payments – Contributions | $3,100 | $3,600 | $3,500 | $10,200 |

| PWGSC Accommodation Costs | $59 | $59 | $47 | $189 |

| Total | $4,700 | $4,800 | $4,500 | $14,000 |

Source: INAC (2008). Climate Change Adaptation for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Initiative. Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk Based Audit Framework.

| Requirement | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 (planned) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ($ '000) | ||||

| Salaries | $428 | $428 | $389 | $1,245 |

| Operating Expenses | $353 | $617 | $689 | $1,841 |

| Employee Benefits Program | $91 | $91 | ||

| Transfer Payments – Grants | - | - | - | - |

| Transfer Payments – Contributions | $1,182 | $4,036 | $4,800 | $10,018 |

| PWGSC Accommodation Costs | $59 | $59 | Not available | $118 |

| Corporate Support | $123 | $115 | Not available | $238 |

| Total | $2,236 | $5,346 | $5,878 | $13,460 |

Sources: Program-provided financial documents.

A review of program expenditures reveals that over the three-year period, projects in the Yukon received the most funding with roughly $2.5 million, or 25 percent of total funding. Projects benefiting communities in the Northwest Territories received approximately $2 million (20 percent of total spending). Nunavut projects totalled $1.2 million (12 percent of the total). [Note 6] Finally, just under a third of project funding ($3.2 million) went to projects in the four provinces of Quebec, British Columbia, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador and 12 percent ($1.2 million) was directed at other projects.

The following funding authorities are being used to support implementation of INAC's Climate Change Adaptation Program:

- Funding Authority 334 - Contribution for promoting the safe use, development, conservation and protection of the North's natural resources. This Authority was to have expired March 31, 2010, but will be renewed April 1, 2010.

- Funding Authority 341 – Contributions for the purpose of consultations and policy development. This Authority expires March 31, 2010.

1.3.4 Program management, key stakeholders, and beneficiaries

Project management & governance

The Program fits into INAC's program architecture within the Environment and Renewable Resources Directorate (ERR) of Northern Affairs Organization and comprises the following:

- Director, ERR, who is responsible for the overall strategic management of the Program.

- Climate Change Coordinator, who operates immediately under the Director, ERR, and is responsible for ensuring that the Program is aligned with corporate policies within INAC's mandate.

- Program Manager, who oversees the program administration, delivery and reporting.

- Program Staff, who areresponsible for the day-to-day operations of the Program including providing technical advice to applicants, supporting the Project Technical Committee, monitoring project implementation and providing support to recipients. [Note 7]

The Program has eight full-time staff including one Program Manager, four Program Analysts, one Policy Analyst, one Project Officer and one Administrative Officer. In the last year of the Program, one of these staff members was seconded to another position. According to program representatives, since the inception of the Program, the distribution of human resource time and effort across various tasks was:

- Reviewing proposals and managing/monitoring funded projects: 33 percent

- Reporting, briefings, and information management: 26 percent

- Communications and developing partnerships: 16 percent

- Program analysis (advisory committee, setting priorities, defining processes): 12 percent

- Audit and evaluation: 7 percent

- Human resources and financial management: 4 percent

- Other: 2 percent

INAC Regional staff, liaise with project applicants and recipients, and assist in the establishment of funding agreements with local project representatives.

In addition, the Program is governed by two committees:

- Program Advisory Committee, comprised of representatives from northern organizations, territorial governments, and other federal departments involved in climate change adaptation and various regional stakeholders. The committee is charged with reviewing the objectives of the Program, discussing the continued relevance of these items, and providing advice to the Program on the overall direction of operations and policy. The Committee became operational in early 2010.

- Project Technical Committee, whichreviews project applications and makes funding recommendations to the Director, ERR.

The Program provides funding to organizations, institutions, communities and individuals who propose a project that is well-matched to the objectives of the Program (refer to Section 1.3.2 above) and targets either northern or Aboriginal communities. Proposal requirements are designed to identify project partners and provide evidence that the project will engage communities. Proposals are selected based on their alignment with the Program's guiding principles; capacity and expertise of project team; consistency of project objectives with those of the Program, including a clear methodology of how project objectives will be achieved and the ability of the project to benefit the targeted community and other communities. The Program does not issue a formal call for proposals.

Key stakeholders and beneficiaries

Key stakeholders include other federal departments, territorial and aboriginal governments, and northern and aboriginal communities.

Targeted beneficiaries are aboriginal and northern communities, national aboriginal organizations, northern organizations, aboriginal community groups (volunteer groups, community associations and institutions), territorial and aboriginal governments, professional organizations, and research institutions.

2. Methodology

This section outlines the evaluation methodology. It describes the data collection tasks and identifies data and analysis limitations.

2.1 Overview

The update evaluation builds on an implementation evaluation of the Program completed in 2009. The implementation evaluation examined the core issues of relevance and performance as outlined in theTBS directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009). Its focus was on the relevance, design and delivery and preliminary results/success of the Program. Field work was completed between July 2009 and October 2009 and the final report was tabled atINAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) meeting in December 2009.This evaluation focuses on the extent to which the Program has achieved its expected outcomes. INAC's EPMRC approved the Terms of Reference for the present evaluation on September 24, 2010. Data collection and analysis was completed between October 2010 and January 2011.

2.2 Evaluation issues and questions

A matrix of evaluation questions, indicators and data sources guided the evaluation. The matrix addressed two TBS core performance evaluation issues: results/success and efficiency, economy and cost-effectiveness. The evaluation questions associated with each issue were:

Results/success

- What progress has the Program made toward achieving its intended outcomes?

- Have there been unintended outcomes as a result of the Program?

Economy, efficiency & cost-effectiveness - How efficient and cost-effective is the Program?

- How does the relationship between the Program and its partners contribute to cost-effectiveness?

- Are there more cost-effective and efficient means of achieving the objectives of the Program?

The evaluation findings (refer to Sections 4 and 5 below) are organized according to these issues. The evaluation questions associated with each issue are listed at the start of each of the findings sub-sections.

2.3 Evaluation methods

This section describes the data sources and analysis processes used in the evaluation, identifies limitations and related mitigating strategies and the reviews the evaluation's quality control measures.

2.4 Data sources and analysis

2.4.1 Data sources

The evaluation methodology included four data collection tasks:

- Document review toupdate the 2009 implementation evaluation and gather evidence program performance. Examples of documents reviewed included the implementation evaluation, performance tracking spreadsheets, quarterly reports, the INAC Climate Change Division's Annual Report for 2008–09, and the Adaptation Theme-level Evaluation report. A cross-jurisdictional review was conducted to determine alternate approaches to climate change adaptation programming.

- Administrative and financial data review to detail the scope of the evaluation and to gather evidence on related to efficiency, economy and cost-effectiveness. This included all available performance data collected as part of the Program's Results-based Management Accountability Framework (RMAF) concerning the number of projects managed by community members, the completion of adaptation plans, risk/vulnerability assessments completed and other performance indicators. Finally, the evaluation team reviewed planned and actual expenditures and performance data.

- File review to gather evidence on project-level outcomes based on a review of final reports for projects funded in the 2008-09 and 2009-10 fiscal years (n=55) and progress reports for projects funded in the 2010-11 fiscal year (n=21). [Note 8]

- Key informant interviews to gather evidence on climate risks and opportunities, partnerships and collaborations, project results and economy, efficiency and cost-effectiveness issues. A total of 28 key informants were interviewed by telephone, including program representatives (n=3), representatives of other federal departments involved in the Adaptation Theme of the CAA (n=2), project leaders (n=19), and provincial and territorial government climate change coordinators and directors (n=4).

A sample of representative project leader key informants was selected using the following considerations: geographical location of project, type of project, type of recipient, and funding year (refer to Annex A for more detail on the extent to which project leaders represented each of these categories). In order to assess the achievement of outcomes to the greatest extent possible, only project leaders from the first two funding cycles (2008-09 and 2009-10) were interviewed. Program managers, both from INAC and other government departments, were selected based on their direct relationship with the Program. Finally, climate change directors and coordinators from other levels of government were invited to participate from the three territories and five provinces where projects were funded.

Two technical reports with detailed summary and analysis were prepared as part of the evaluation: an updated document, data, and file review report and a key informant interview summary report.

2.4.2 Analysis

Presentation of findings

Where possible, the evaluation findings included in Sections 4 and 5 are based on triangulation of all of the lines of evidence to ensure the strongest possible analysis and to mitigate the impact of limitations on the evaluation. The strength of the support for the findings presented is assessed as follows:

- Substantial – all lines of evidence provide strong support for the finding;

- Considerable – most lines of evidence provide some support for the finding; and

- Some – few lines of evidence support the finding and/or there is limited support for the finding.

Additionally, the terms listed in Table 4 are used to refer to the proportion of key informants in agreement with an opinion:

| Term | Percentage range |

|---|---|

| All | 100% |

| Almost all | 80-99% |

| Many | 50-79% |

| Some | 20-49% |

| Few | 10-19% |

| Almost none | 1-9% |

| None | 0% |

The findings section is divided into two subsections: results/success and efficiency, economy and cost-effectiveness. The headings within each section respond to the evaluation question being addressed.

Gender-based, sustainable development & self-governemnt analysis

In line with departmental policies, INAC's evaluations apply gender-based and sustainable development lenses to analysis when possible. In addition, evaluation reports attempt to share lessons learned from self-government experiences. Analysis in this evaluation is limited to sustainable development analysis (refer to Section 4.4 below), the one form of analysis of the three where information was available and subject matter applied.

2.5 Evaluation limitations and mitigating strategies

The evaluation encountered the following data and analysis limitations and developed mitigating strategies as a result:

- Benchmark comparison. Benchmark data on climate change awareness and capacity to address issues of climate change were not collected prior to the start of the Program. Consequently, the evaluation could not determine the extent to which the Program increased awareness of climate change adaptation issues. As a mitigating strategy, key informants were asked to comment on the extent which they believe the Program raised awareness among community members and whether communities have the capacity to adapt to climate change as a result of the Program.

This limitation impacted the ability of the evaluation to fully assess the extent to which the Program has contributed to greater awareness and increased capacity among beneficiary communities. - Limited key informant perspectives. Information on awareness of climate change and perceptions of the value of the program were not available in project final reports. It is important to note that community members, the best source of this information, were not interviewed.

As a mitigating strategy, project leaders were asked to comment on the extent to which communities and individuals benefited from the Program.

The impact of this limitation on the evaluation was minimal as most projects are at the stage of identifying, assessing, and prioritizing risks and adaptation strategies, rather than putting these strategies into use. Nevertheless, important information relating to the Program's ability to support these community-level outcomes was only captured indirectly, leading to the risk of data bias. - Achievement of outcomes. As the evaluation was conducted during the final year of the three-year program, it was difficult to assess the extent to which outcomes have been achieved.

As a mitigating strategy, the evaluation questions at times combine several of the Program's intended outcomes in an attempt to broaden analysis. For example, the development of guidance material for safer and more reliable infrastructure was assessed as part of availability of information. In another example, the intermediate outcome of increased professional and institutional capacity was combined with the Program's long-term outcome of increased capacity among Aboriginal people and northerners to adapt to climate change impacts.

In addition to this approach, the evaluation focused analysis on whether the program appears to be on track to achieve its intermediate and long-term outcomes. When interpreting findings in Sections 4 and 5, the reader needs to consider that the Program was operational for roughly two years at the time of the evaluation.

The early timing of the evaluation had a fairly significant impact as useful outcome information, for instance relating to the use of adaptation plans, was not available. - Performance and financial information. There was limited performance information available both at the program-level and in the final reports of projects. In addition, it was difficult to determine with accuracy the total cost of funded projects as some were able to leverage funding from a variety of sources. As a mitigating strategy, the evaluation relied on key informant interviews for much of the information related to outcomes. This was supplemented with all available performance and financial data.

The overall impact of this limitation was minimal as a representative group of key informant interviewees from several stakeholder groups and other interested parties involved more generally in climate change adaptation adequately answered evaluation questions related to performance.

2.6 Quality control

The following quality control measures were undertaken during the evaluation:

- An evaluation matrix based on the Program RMAF and other key program documents guided all stages of the evaluation including design of research instruments, analysis in technical reports and finally, reporting.

- PRA administered the key informant interviews and members of INAC observed many. Key informant interviews were audio-recorded and interview notes were sent back to key informants for validation.

- Representatives from the Program reviewed and provided comments on the methodology report, preliminary findings PowerPoint presentation and the draft report.

- The methodology and draft report underwent a process of internal EPMRB peer review.

- An advisory committee consisting of four members with extensive knowledge and expertise of climate change issues both north and south of 600 reviewed the 2009 implementation evaluation methodology and participated in a focus group. Input from this group was considered in the development of this evaluation update.

3. Evaluation findings - Summary of the 2009 implementation evaluation

This section summarizes the findings of the 2009 implementation evaluation of the Program.

Relevance

- The Program is relevant to northerners and Aboriginal communities and addresses the continued need to adapt to climate change. The implementation evaluation concluded that there is a continued need for climate change adaptation planning and implementation programming in the North because:

- This three-year program does not have the capacity or resources to reach all of the communities in the North.

- Without continued support, communities are unlikely to implement their adaptation plans and therefore will revert to using a reactive model to respond to climate change issues.

- No other climate change adaptation programs target the North.

- This three-year program does not have the capacity or resources to reach all of the communities in the North.

- The Program aligns well with federal priorities.

- The Program forms part of the CAA, which represents Canada's commitment to addressing climate change.

- The Program contributes to three of INAC's strategic outcomes: The North, The People and The Land.

- The Program forms part of the CAA, which represents Canada's commitment to addressing climate change.

Design & Delivery

- The Program was essentially implemented as planned although some challenges were encountered.Two significant implementation challenges were:

- Delays in obtaining communications approval prevented the Program from launching a formal communications strategy to raise awareness of the funding opportunity. To overcome this challenge, program staff proactively contacted communities to tell them about the Program and help them identify research needs and prepare proposals.

- The Program was not fully staffed until summer 2009 and there was little capacity among project leaders and awareness to build project proposals and implement the projects. Therefore, the Program did not have sufficient human resources to review proposals and manage projects. This led to the Program's re-profiling of $600,000 in funding from 2008-09 to 2009-10.

- Delays in obtaining communications approval prevented the Program from launching a formal communications strategy to raise awareness of the funding opportunity. To overcome this challenge, program staff proactively contacted communities to tell them about the Program and help them identify research needs and prepare proposals.

Results

- The Program is beginning to make progress toward its immediate outcomes. The implementation evaluation found evidence of the following progress toward outcomes:

- A wide range of stakeholders such as scientists, consultants, experts, and communities are collaborating on climate change adaptation projects.

- The Program has brought technical expertise into northern communities and projects are developing climate change adaptation information that is accessible and relevant to these communities.

- Communities are assessing climate change risks and opportunities and defining adaptation priorities. While projects are developing adaptation tools, there are no processes in place to track how they are being used.

- It was not possible to determine whether climate change or adaptation information was being integrated in planning and decision-making processes (refer to Section 4.4 below for an update).

- A wide range of stakeholders such as scientists, consultants, experts, and communities are collaborating on climate change adaptation projects.

Update on implementation evaluation recommendations

In the past year, the Program has made considerable progress in addressing the recommendations of the implementation evaluation. The Program has partnered with the Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), Council of Yukon First Nations, McGill University and the Delphi Group to review existing adaptation work and conduct an environmental scan/needs assessment for each territory, Inuit land settlement areas and First Nations south of 600. Communication and coordination have been improved by updating the Program website and increasing the regularity of meetings with INAC's ecoENERGY program, Territorial adaptation offices and INAC Regional offices. Finally, the Program has taken steps to improve the quality of performance information and reporting processes by revising the performance tracking system and completing annual reports through the Horizontal Management, Accountability and Reporting Framework (HMARF).

3.1 Relevance, design and delivery update

3.1.2 Need for adaptation support

Following findings discussed in detail in the 2009 evaluation, program representatives and project leaders indicated there is a continued need for the Program. These individuals mentioned that there is a need to continue to build capacity and work with communities that have not begun to engage in adaptation planning. Similarly, there was a trend of increasing demand for the program over its three-year duration. The Program met its target of funding 20 projects per year in 2008-09 and exceeded it in 2009-10 (n=36) and 2010-11 (n=30), by June 2010, the Program was oversubscribed.

Not all communities in need of support have the necessary capacity to participate in the Program as it is currently delivered. Many program representatives and project leaders cautioned that some of the communities most in need are also faced with a number of other urgent issues and therefore may not have financial and/or human resources to devote to climate change adaptation projects.

3.1.2 Responsiveness to need

Despite increasing interest in the Program, the extent to which the Program reached new proponents decreased in each funding year. In 2008–09, 17 unique proponents received funding. Of those, 10 received funding in 2009–10 along with eighteen new recipients. In 2010–11, the Program funded two new proponents and 19 of the previous proponents who were funded. In total, seven proponents received funding in all three years of the Program. Nevertheless, one should interpret these figures with caution as much of the success of the program can be attributed to its ability to provide sustained support to a number of projects over funding years.

The file review and key informant interviews revealed with substantial evidence that projects funded through the Program directly respond to climate change needs. However, the evaluation did not find evidence that the Program reached the communities in greatest need of support, or conversely, that it applied a structured approach to identify communities that possess existing capacity and interest (discussed in greater detail in section 5 below). An analysis of Community Well-being Index (CWB Index) scores of communities that benefited from the program, however, shows that the Inuit and First Nations communities benefiting from the Program had a slightly higher CWB Index score than the overall average for these groups. These results, shown in Table 4 below, may suggest that the program benefited communities with some existing capacity.

| Community | Average project CWI score | Average population CWI score |

|---|---|---|

| First Nations | 62 | 57 |

| Inuit | 64 | 62 |

| Other | 71 | 77 |

Key informant interviewees questioned whether the Program was able to identify the communities with the greatest or most immediate need for support. Many of the reasons for this step from the fact that the Program has just recently begun and processes to target communities are not yet in place. As discussed in the implementation evaluation, the Program was not able to launch a widespread communications strategy to inform communities of the Program due to delays in approval. Therefore, the Program used mostly informal means to inform communities about the Program. For example, to solicit interest in the program, staff contacted communities and stakeholders they had existing relationships with as well as communities they believed could immediately start on projects. A few project leaders said they did not become aware of the Program until it was in its second or third year. Others said they did not have a clear understanding of the types of activities eligible for funding. Funding applications were reviewed and approved on a first-come, first-served basis, without giving consideration to need or existing capacity.

As noted above, in response to a recommendation from the 2009 implementation evaluation, the Program has been conducting a gap analysis to better target communities in greatest need as well as those with existing capacity to undertake adaptation work. In addition, some work in this area is being planned in the provinces and territories. For instance, the government of Yukon will be conducting a community needs assessment. Data from this survey will help to identify priority communities.

4. Performance - Results

This section provides key findings related to the results of the Program. It discusses progress towards immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes.

Immediate outcomes

4.1 Collaboration

This section responds to the following evaluation question: What progress has the Program made toward greater collaboration to address issues of climate change?

The evaluation found substantial evidence that the program contributed to successful partnerships. To a far lesser extent, collaboration challenges hindered project success.

Collaboration successes

Program-level

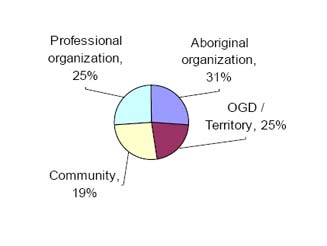

Over its three year duration, the Program funded 38 proponents including research organizations (n=13), including consulting firms and related Aboriginal organizations; community councils (n=7); Aboriginal governments (n=7); associations (n=6), such as planning and standards associations; territorial governments (n=3); and academic institutions (n=2).

Table 6 shows the number and value of projects funded by recipient type and fiscal year.

| Proponent type | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projects | ||||||||

| Number | Value | Number | Value | Number | Value | Number | Value | |

| Research organizations | 8 | $506,900 | 16 | $1,648,600 | 9 | $1,674,500 | 33 (38%) | $3,830,000 (40%) |

| Territorial governments | 2 | $95,000 | 6 | $820,500 | 7 | $760,600 | 15 (17%) | $1,676,100 (17%) |

| Community councils | 3 | $142,900 | 4 | $429,600 | 5 | $856,200 | 12 (14%) | $1,428,700 (15%) |

| Aboriginal governments | 4 | $302,500 | 4 | $465,300 | 5 | $643,300 | 13 (15%) | $1,411,000 (15%) |

| Associations | 2 | $158,000 | 5 | $548,900 | 3 | $349,500 | 10 (12%) | $1,056,300 (11%) |

| Academic institutions | 1 | $30,000 | 1 | $107,400 | 1 | $64,600 | 3 (3%) | $202,100 (2%) |

| Total | 20 | $1,235,300 | 36 | $4,020,300 | 30 | $4,348,700 | 86 | $9,604,200 |

Source: Program performance measurement summary spreadsheet

Funding a broad range of recipients has enabled the Program to foster the development of relationships between scientists, consultants, experts and communities. Many program representatives reported that, in addition to its role as funder, the Program has helped researchers and communities identify partners. They believe the program has been able to get the right people to provide the right information and expertise to communities.

CAA level

The Program worked to strengthen its relationships with other federal departments involved in the Adaptation Theme of the CAA such as such as NRCan, Environment Canada and Health Canada. These departments have been working together on program renewal processes, participate in each other's workshops and are considering issuing joint calls for proposals in future programs.

Since the completion of the implementation evaluation, the Program has established a Program Advisory Committee consisting of regional stakeholders, northern organizations, territorial governments, and other federal departments involved in adaptation.

Collaboration challenges – Project level

The evaluation found evidence of several challenges to collaboration at the project-level. While almost all project leaders said project-level partnerships were successful, they identified some challenges that should be considered in future partnerships:

- It can be difficult to achieve shared vision, especially if partners have different research interests or approach the project from different research disciplines.

- Community-level and territorial-level contacts change due to staff turnover.

- Community members may experience consultation fatigue if more than one project is being conducted in a specific community.

- Some community members may be reluctant to participate in discussions and workshops marketed as relating to climate change. They may associate climate change with large catastrophes or traumatic events or they may be overwhelmed by the problem.

- A recurring theme that emerged during many key informant interviews was the difficulty of maintaining long-term relationships due to the uncertain future of the Program. Program representatives reported the need to reject some good applications due to funding limitations could damage relationships. They also mentioned that partnerships are losing momentum because it is not clear what future funding, if any, will be available for adaptation-related projects. Further, a few project leaders cautioned that funding interruptions may lead to the loss of important project resources such as project coordinators, community contacts and experts whose positions depend on program funding.

4.2 Available information and expertise

This section responds to the following evaluation question: What progress has the Program made toward increased availability of and access to information, technical expertise, and products on adaptation to climate change?

The evaluation found considerable evidence that the Program is contributing to increased availability of and access to information, technical expertise and other adaptation products. However, some evidence suggests areas for improvement and the need for additional work.

Successes

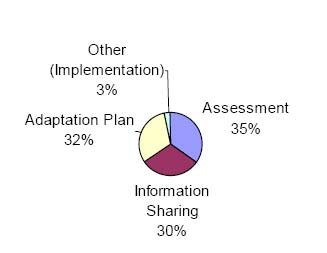

Almost half of the funded projects (n=41) focused on assessment of climate change risks and impacts. While these projects are not intended to result in the development of adaptation plans, they are generating information and tools that communities may be able to use to inform their planning and adaptation work.

To a lesser extent, funded projects focused specifically on information-sharing activities and awareness building (24 percent, n=21) and the development of adaptation tools (9 percent, n=8).

- Information-sharing projects involved workshops (n=8); state-of-knowledge and/or gap analysis reports (n=5); development of climate change scenarios (n=4); development of success stories (n=2); and community visits to raise awareness of climate change (n=2). The eight formal workshops addressed a variety of issues such as raising awareness of climate change and data analysis. It should be noted that other types of projects, such as adaptation planning, often involved an awareness-building component. For instance, a recent audit of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development of Government of Canada climate change adaptation including INAC's program, highlights a planning project funded in Clyde River as an example of how scientific information was successfully shared with the community through a variety of means including, workshops, presentations and community gatherings. [Note 9]

- Adaptation tools were developed for:

- Water-related assessments and monitoring including a protocol to conduct site-specific assessments of vulnerabilities in water and wastewater systems, an adaptation of Engineers Canada's Engineering Vulnerability Assessment Protocol, a Water Information Tool and a guidebook for the use of data loggers to measure water temperatures.

- Assessing and monitoring infrastructure vulnerability including a methodology for conducting a vulnerability assessment of community infrastructures in terms of permafrost degradation and a methodology for the installation of adfreeze piles.

- Community-based adaptation planning including a risk-based guide outlining a process for approaching climate adaptation issues in communities North of 600, a workbook for community-based adaptation planning, and a success stories publication and webcast.

- Water-related assessments and monitoring including a protocol to conduct site-specific assessments of vulnerabilities in water and wastewater systems, an adaptation of Engineers Canada's Engineering Vulnerability Assessment Protocol, a Water Information Tool and a guidebook for the use of data loggers to measure water temperatures.

Project recipients indicated that these information sources and tools may be used in future projects.

Program representatives and some project leaders said the Program has made support available to participating communities by connecting proponents with experts and organizations to partner with. Some program recipients also mentioned that NRCan may be able to provide communities with scientific expertise and territorial governments may be able to provide planning and engineering expertise.

Areas for improvement & work needed

Although there is substantial evidence of information being shared within projects, there is a need for increased sharing of results between projects and across communities. A considerable amount of climate change research is occurring and there is a need to amalgamate and synthesize findings. Few projects are at the stage of being able to share information. However, some information is being shared through informal conversations, posting information on the Internet, and presentations to communities, Aboriginal and other organizations, and workshops and conferences. INAC posts some information about funded projects on its website [Note 10] and refers communities of available information upon request; however, the Program does not formally facilitate information-sharing between communities and across funded projects. According to Program managers, these include risk assessment guidelines and Public Infrastructure Engineering Vulnerability Committee guidelines. Suggestions for improvement in this area can be found in Section 6 below in relation to efficiency and economy. Further, respondents mentioned that many of the funded projects are developing and testing methodologies and processes. These tools may become available for use in future projects.

Key informants identified several areas for improvement and additional/ongoing work.

- Some program representatives and project recipients said there will always be a need to provide outside expertise, as it cannot be expected to be retained within individual communities.

- Some program recipients discussed the need for local or territorial climate change coordinators to ensure climate change continues to be a priority, to liaise with government departments, and to connect communities with appropriate partners. Several respondents thought that there is an ongoing need for comprehensive baseline data such as climate scenarios that can be used to support decision-making.

4.3 Identification and assessment of climate change risks

With information, tools and other resources such as expertise becoming increasingly available, the next question the evaluation sought to answer was to what extent are these resources being used and what role do they play in increasing community involvement in assessing risks and opportunities.

Community identification of risks and opportunities

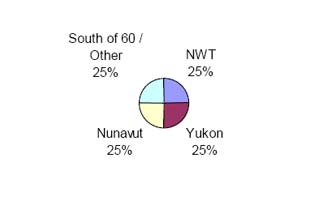

Key informants emphasized the strong role communities have played in identifying and assessing climate change risks and opportunities. They noted that there is a high level of community interest in these discussions, and in many cases, communities have ownership over the assessment process. Based on the file review, by the conclusion of the Program, community consultations to identify risks and opportunities will have occurred in 32 communities including:

- eleven South of 600

- ten in the Northwest Territories

- six in Yukon

- five in Nunavut.

Project leaders identified a vast range of climate risks such as increased severity and duration of extreme weather events, unpredictable freezing and thawing, permafrost degradation, flooding, landslides, reduced ice thickness, warmer waters and shoreline erosion.

Key informants reported that these climate risks can lead to impacts such as infrastructure vulnerability; diminished water quantity and quality; loss of traditional land-use practices and cultural identity (e.g., species hunted, traditional medicinal ingredients); food security issues; road wash-outs; increased risk of forest fires; introduction of invasive species and bacteria; changing animal migration patterns and increased presence of problem animals in communities. Project leaders noted that while most communities in a geographical region face the same risks, the magnitude of risk may differ. For example, they explained that some communities have different warming trends and/or permafrost conditions.

Most project leaders noted that communities have yet to recognize opportunities resulting from climate change. Some of the opportunities that were identified include a longer growing season, longer shipping season, increased tourism, increased forest growth, increased grasslands available for animals and lower heating bills.

Scientific assessment

About one-quarter of the projects (n=25) focussed on scientific assessment of climate risks laying the groundwork for regional climate change trend analysis and providing raw data which many informants felt was crucial to successful planning activities.

- Seventeen of the projects were conducted in the Territories including nine in Yukon, six in the Northwest Territories and two in Nunavut. Five were conducted South of 600 and two focussed broadly on the North.

Most of the scientific assessment projects were led by research institutes or consultants (n=9), community councils or associations (n=7), or territorial governments and other federal government departments (n=8). One project was community-led. - Scientific assessments investigated water risks (n=8); permafrost risks (n=7); sea-level rise and sea-ice risks (n=4); risks to tree species (n=3) and other risks (n=3). Table 7 describes the projects that involve scientific assessment.

| Climate risk | Funded projects |

|---|---|

| Water |

|

| Permafrost |

|

| Sea-level rise and sea-ice risks |

|

| Tree species |

|

| Other risks |

|

Source: Final reports for funded projects

Intermediate and long-term outcomes

4.4 Capacity to adapt to climate change

This section focuses on the following evaluation question: What progress has the Program made toward increased capacity of aboriginal and northern communities to adapt to climate change? In addition, to the greatest extent possible, it speaks to Program outcomes concerning professional and institutional capacity and the integration of climate change information into planning and decision-making.

A study on adaptive capacity discusses a range of conditions that together form capacity. Among others, these include the availability of technology and other information resources, human and social capital, the ability of decision-makers to manage information and a public understanding of the source of the risk and its significance. [Note 11] Building on the outcome sections above, this and the next section discuss elements of this list as they apply to the development of capacity and the use of this awareness and skill set to begin to take actions to adapt to a changing climate.

As mentioned in the limitations section above, not enough time has passed to properly assess the extent to which the Program has contributed to increased capacity. With that said, early evidence points to the fact that funded projects are making progress towards this outcome.

Awareness-building and influencing decision-making

The file review found that, typically, projects do not focus specifically on building capacity, but rather involve a capacity building component. This might take the form of information sharing, or as discussed in greater detail above, active participation of community members in adaptation projects by identifying climate risks and opportunities and defining possible responses to them. Key informant interviews revealed that through this participation, these community members have gained a better understanding of the climate risks their community is facing and have learned about some of the actions they can take as individuals to begin adapting to climate change.

Many project leaders said communities are acutely aware that climate change is occurring, as they live witness it on a daily basis. Nevertheless, there is a need for continued effort in this area. Some community members are questioning whether the changes being experienced are the result of long-term climate change or simply reflect unusually variable weather. Sustained awareness of the impacts of climate change and motivation to act on this awareness often requires repeat messaging.

Some key informants said the program has increased communities' capacity to understand, support and benefit from research. For example, program representatives and project leaders noted that by engaging communities in projects, community members are developing relationships with experts, receiving adaptation training and ensuring project results/reports are useful to communities. Program representatives also indicated that involving communities in research projects helps ensure that decision-makers are accessing the information needed to inform decision-making processes.

In addition to the Program's role in raising awareness among community members, there is some indication that information from projects has begun to be fed into the realm of local-level decision-making. Several respondents agree that projects have helped community leaders make linkages between climate change and community needs. Through an understanding of basic issues, these individuals have a better ability to plan and prioritize realistic actions in response to climate risks.

Other capacity building activities

Students, community members, and others have received training related to monitoring activities through six projects (7 percent). This training was related to the monitoring of permafrost, water sources, sea ice, air and ground temperatures, weather, and shoreline erosion. Other projects (n=15, 17 percent) have hired local residents to serve as project coordinators or have invited them to participate in project advisory or steering committees. It is unknown if the community members who participated in these projects have used the skills gained to support other climate change adaptation work.

The Program has worked to strengthen the capacity of territorial governments. The Program funded territorial-led projects in all three funding years. During this time, key informants said the Program increased territorial governments' understanding of the impacts of climate change, ensured climate change is considered in government and community planning processes, and created the forum to discuss joint priorities for the future. With greater capacity, informants believe territorial governments will be better able to fulfil their role as the primary source of support for northern communities. Program representatives and representatives of other federal departments believe that once additional capacity is built in territorial and Aboriginal governments, responsibility to continue adaptation planning and implementation could be devolved to them.

Finally, the Program's role in facilitating community engagement and increasing community capacity sets communities on the right track to achieve sustainable development. It is clear that the Program directly contributes to several of INAC's sustainable development principles among others including: engagement of interested local communities and organizations when planning and implementing federal programs and decisions based on the best available, scientific, traditional and local knowledge. Of course, sustainable development will occur only if the funded projects influence decision-making, or spur-on individual and community level action to address climate change issues.

4.5 Action to reduce vulnerability

This section responds to the following evaluation question: What progress has the Program made toward aboriginal and northern communities taking action to reduce their vulnerabilities from and adapt to climate change impacts and realize opportunities?

Adaptation planning

The evaluation found some evidence that communities are developing adaption plans. By the end of the Program, adaptation plans will be in place for 15 communities including seven communities in the Northwest Territories, five communities in Nunavut, and three communities South of 600. The plans are being developed through 10 projects (or 12 percent of all projects); nine of these received more than one year of funding. The following are noteworthy findings related to the Program's support of adaptation planning:

- The Program directed $2.0 million in funding (or 21 percent of all the funding provided to projects) to the development of adaptation plans.

- Most of the adaptation plans are being prepared under the guidance of an external consultant. Research or professional organizations are leading six of the projects. Three of the projects are being led by Aboriginal governments; one of these Aboriginal governments worked with an external research organization to develop the adaptation plans for the communities in its jurisdiction.

- The development of a community adaptation plan can take one to three years to complete. The process typically involves the development of a project advisory committee and community consultations to identify and prioritize risks/opportunities and plan potential adaptation strategies. It may also involve special projects to further assess specific risks. Typically the organization or researcher leading the project will prepare a draft adaptation plan for review and approval by the community.

Table 8 provides a brief overview of the ten projects expected to result in the development of an adaptation plan in fifteen communities.

| Lead | Communities | Cost | Duration | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Institute of Planners | Nunavut:

|

Total: $537,000 Per community: $107,400 |

3 years |

|

| Tlicho Government with support from Ecology North | Northwest Territories:

|

$648,000 Per community: $162,000 |

2 years |

|

| Ecology North | Northwest Territories:

|

$338,000 | 2 years |

|

| Arctic North Consulting | Northwest Territories:

|

Total: $195,000 Per community: $97,500 |

1 year |

|

| Hesquiaht Band | Clayoquot First Nations, British Columbia:

|

Total: $250,000 Per community: $83,000 |

2 years |

|

Source: Final reports for funded projects

The evaluation found some evidence that the adaptation plans funded through the Program were worthwhile investments. Though only recently completed or still underway, key informants were optimistic that adaptation planning would influence decision-making and that elements of the plans would be implemented, depending on associated costs. Another benefit of the planning process cited was its ability to bring together numerous viewpoints and knowledge from a range of community members, experts and other stakeholders.

Alternatively, a few program recipients suggested that some of the adaptation plans that have been prepared may not be as useful to the communities as initially intended. Possible reasons for this are that these adaptation plans were not based on concrete data, there was little community representation in consultations and there was no community ownership of the planning process.

4.6 Unintended Outcomes

Implementation

Although implementation of adaptations and other actions was not an objective of the Program, the evaluation found some evidence that communities are beginning to take action to reduce their vulnerability to climate change.

Although many program recipients indicated that communities have yet to begin implementing adaptation projects, they provided some examples of actions communities are taking to respond to climate change as a result of knowledge and resources gained through the Program. These include: changing travel routes, hunting different species, planning development on higher ground and constructing breakwaters.

Based on the file review, three of the funded projects specifically involved implementation activities (although reports were only available for two of them).

- One project involved developing two sea ice safety courses – one for K to 12 students and the other for young adults and apprentice hunters – and continuing sea ice monitoring activities, which began in 2006 with funding from the National Science Foundation.

- A second project involved holding workshops related to fuel tank and hazardous material awareness.

4.7 Best practices and lessons learned

Best practices

A number of key informant interviewees from all groups shared best practices and lessons learned around climate change initiatives:

- Information database. To address a lack of coordination in information management, one province is developing a one-stop adaptation information database that will include key information about climate change vulnerability, tools to help communities adapt, climate change modelling and scientific data from Natural Resources Canada and Environment Canada.

- Resilience-based capacity-building. Two provinces have adopted a resilience-based approach to community capacity-building. Instead of taking a risk mitigation approach, these provinces encourage resilience in the face of vulnerability. The underlying belief to this approach is that strong communities will naturally be better able to adapt to the impacts of climate change as they occur. Moreover, this approach is in keeping with an Aboriginal worldview.