Archived - Formative Evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education Program On Reserve

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Evaluation Matrix

- Appendix B - Interview Guides

List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

The formative evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education (conducted in 2009-10) will be followed by a summative evaluation of Elementary/Secondary Education in 2010-11 and to be completed in 2011-12, in accordance with the agreement reached between Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Treasury Board Secretariat in May 2008. The formative evaluation study is required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program, which expire March 31, 2010. The summative evaluation will begin in 2010-11 and be completed in 2011-12, in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13.

While the summative evaluation scheduled for 2010-11 is intended to entail a systematic review of educational outcomes with meaningful engagement of First Nations and Inuit education representatives, this evaluation addresses relevance and, to the extent possible, performance. Further, this study provides a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education in INAC; reviews existing literature on First Nations education; and provides some additional insight on assessing educational outcomes in order to lay the groundwork for the summative evaluation. Recommendations for major policy or program changes are deferred to the summative evaluation.

The overall objective of elementary/secondary education programming is to provide eligible students living on reserve with education programs comparable to those that are required in provincial schools by the statutes, regulations or policies of the province in which the reserve is located. It is expected that eligible students will receive a comparable education to other Canadians within the same province of residence, with similar educational outcomes to other Canadians and with attendant socio-economic benefits to themselves, their communities and Canada.

The evaluation examined elementary and secondary education program activities including: instructional services for Band Operated Schools, Federal Schools and Provincial Schools; Elementary and Secondary Student Support Services; New Paths for Education; Teacher Recruitment and Retention; and Parental and Community Engagement.[Note 1] It further considered INAC's Cultural Education Centres Program, last evaluated in 2004.

In line with Treasury Board requirements, the evaluation looked at issues of relevance (i.e., continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities), performance (demonstration of efficiency and economy) and design and delivery.

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of four main lines of evidence (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix[Note 2]): Literature review; Document and File review; data analysis; and key informant interviews.

Conclusions:

There was a clear demonstration of need with respect to improving the rates of high school completion; addressing funding gaps between First Nation and non-First Nation schools; and addressing Aboriginal-specific learning needs as well as circumstances unique to First Nations including the need for more culturally-appropriate learning. Additionally, the intent of elementary/secondary education programming is consistent with Government of Canada objectives of eliminating systemic barriers faced by Aboriginal populations and facilitating participation in the labour market and economic success. However, there is a lack of clarity with respect to roles and responsibilities and their alignment with program objectives; specifically, the delineation of roles and responsibilities with respect to program design and operation, and with respect to First Nations control of Education.

While detailed analysis of resources (to be incorporated in the summative evaluation) was not available for the current study, evidence detailed in the literature and by key informants indicated a lack of resources to achieve the identified objectives such as provincial comparability. Additionally, one of the most pervasive themes in the literature and among key informants was that the approach to First Nations funding for education is not based on current cost realities. In particular, the recurrent theme with respect to resource limitations was capacity building. It was noted repeatedly that the two percent cap on First Nations spending means that while costs inflate, resources do not keep pace with needs relative to non-First Nations schools.

While data from Nominal Roll, to be used in the summative evaluation, will provide a more complete picture of student results, Canadian Census data suggest that there have been noticeable improvements among Aboriginal populations in educational attainment overall. However, further analysis reveals that such improvements are very modest or non-existent within First Nation communities on reserve. Various reports and studies indicate that this issue is prevalent in other countries as well, and that emphasis on culturally-appropriate and relevant learning appears to show promise with respect to increasing success of First Nations students.

Also of key importance, reporting regimes of data collected by INAC that existed over the period of study have not been adequate to provide meaningful analysis of outcomes in relation to program investments.

Based upon these findings, it is recommended that:

- INAC, with meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, explores alternatives to current funding and delivery approaches to better utilise resources and achieve desired outcomes, while retaining the principles of First Nations Control of Education;

- INAC ensures that it is comprehensively analysing the information collected in the Nominal Roll tool to track student outcomes in order to maximise its ability to meaningfully report on outcomes;

- INAC ensures its new approach to collecting data allows for the ability to link and systematically mine data on expenditures and outcomes; and

- INAC, with significant input from First Nations education representatives, clarifies roles and responsibilities of the Department, keeping in mind its responsibility to report results to Canadians.

Management Response / Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. INAC, with meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, explores alternatives to current funding and delivery approaches to better utilise resources and achieve desired outcomes, while retaining the principles of First Nations Control of Education. | INAC, with input from First Nation education, will review and undertake analysis of existing data and research on current funding for First Nation elementary and secondary education including comparisons with provincial tuition rates. | Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Operations, Regional Directors General, CFO. | March 2011 |

| 2. INAC ensures that it is comprehensively analysing the information collected in the Nominal Roll tool to track student outcomes in order to maximise its ability to meaningfully report on outcomes. |

INAC will review the data captured in the Nominal Roll to determine the relevant and pertinent data needed to support improved reporting on outcomes. The Education Information System, presently under construction, will improve the ability to report to Canadians. |

Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Operations, Corporate Information Management Directorate, Regions. | Education Information System launch planned for September 2012. |

| 3. INAC ensures its new approach to collecting data allows for the ability to link and systematically mine data on expenditures and outcomes. | The Education Information System, presently under construction, will provide the ability to collect, link and report on the financial and non-financial data, and will support mining the data to accurately report on expenditures and outcomes. | Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Directors General, Regional Operations. |

2012-13 |

| 4. INAC, with significant input from First Nations education representatives, clarifies roles and responsibilities of the Department, keeping in mind its responsibility to report results to Canadians. | Post-secondary education is a matter of shared responsibility and reciprocal accountabilities, where all share an interest in improving results. |

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The formative evaluation of the Elementary/Secondary Education (conducted in 2009-10) will be followed by a summative evaluation of Elementary/Secondary Education in 2010-11, to be completed in 2011-12, in accordance with the agreement reached between Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Treasury Board Secretariat in May 2008. The formative evaluation study is required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program, which expire March 31, 2010. The summative evaluation will begin in 2010-11 and be completed in 2011-12, in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13.

While the summative evaluation scheduled for 2010-11 is intended to entail a systematic review of educational outcomes with meaningful engagement of First Nations and Inuit education representatives, this evaluation addresses relevance and, to the extent possible, performance. Further, this study provides a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education in INAC; reviews existing literature on First Nations education; and provides some additional insight on assessing educational outcomes in order to lay the groundwork for the summative evaluation.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the Parliament of Canada legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians." Canada exercised this authority by enacting the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, the enabling legislation for the Department of Indian and Northern Development (DIAND). The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary school services to Indian children living on reserves, providing the Department with a legislative mandate to support elementary and secondary education for registered Indians living on reserve.

However, the Indian Act does not discuss social programming. Since the early 1960s, DIAND (currently referred to as Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, or INAC) has sought incremental policy authorities to undertake a range of activities to support the improvement in the socio‑economic conditions and overall quality of life of registered Indians living on reserve. These activities include support for cultural education for Indians and Inuit. Thus, DIAND's position is that the Department's involvement in cultural education programs is a matter of policy as opposed to legislation.

Although there have been significant gains since the early 1970s, First Nation participation and success in elementary and secondary education still lags behind that of other Canadians. Drop‑out rates are higher for First Nations than other Canadian students. Increasing Indian and Inuit retention rates and successes at the elementary/secondary programming level will support the strategic goal of greater self-sufficiency, improved life chances, and increased labour force participation.

INAC's elementary and secondary programming is primarily funded through the following authorities:

- Grants to participating First Nations and First Nations Education Authority pursuant to the First Nations Jurisdiction over Education in British Columbia Act;

- Grants to Indian and Inuit to provide elementary and secondary educational support services;

- Grants to Inuit to support their cultural advancement;

- Payments to support Indian, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education (including Cultural Education Centres; Indians Living On Reserve and Inuit; Registered Indian and Inuit Students; Special Education Program; and Youth Employment Strategy);

- Grants for Mi'kmaq Education in Nova Scotia;

- Contributions under the First Nations SchoolNet services to Indians living on reserve and Inuit;

- Contributions to First Nation and Inuit Governments and Organizations for Initiatives under the Youth Employment Strategy Skills Link program and Summer Work Experience Program; and

- Contributions to the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation.

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

According to the program's Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF), the overall objective of elementary/secondary education (ESE) programming is to provide eligible students living on reserve with education programs comparable to those that are required in provincial schools by the statutes, regulations or policies of the province in which the reserve is located. It is expected that eligible students will receive a comparable education to other Canadians within the same province of residence, with similar educational outcomes to other Canadians and with attendant socio-economic benefits to themselves, their communities and Canada.

The objective of the Cultural Education Centres (CEC) Program is to support Indian and Inuit communities in expressing, preserving, developing and promoting their cultural heritage through the establishment and operation of Indian and Inuit CEC.

Education falls under INAC's strategic outcome, "The People," whose ultimate outcome is "individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit." Education is its own Program Activity, which includes the following sub‑activities (SA) covered in this evaluation: Elementary and Secondary Education and CEC.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The management of education programming at INAC is undertaken by the Education Branch in the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector (ESDPP).

Contributions for the ESE program may be flowed directly to chiefs and councillors, or to organizations designated by chiefs and councillors (bands/settlements, tribal councils, education organizations, political/treaty organizations, public or private organizations engaged by or on behalf of Indian bands to provide education services, provincial ministries of education, provincial school boards/districts or private education institutions).

In addition, INAC may enter into agreements: directly with provincial education authorities for the delivery of elementary/secondary education services; with private firms to administer program funds jointly with or on behalf of the First Nation (i.e., co‑managers, or third‑party managers); or in some cases, INAC may deliver services directly (e.g., in the remaining seven federal schools).

In order to be eligible for elementary/secondary education, a student must:

- be attending and enrolled in a federal, provincial, a band‑operated or a private/independent school recognized by the province in which the school is located as an elementary/secondary institution;

- be aged 4 to 21 years (or the age range eligible for elementary and secondary education support in the province of residence) on December 31 of the school year in which funding support is required, or a student outside of this age range who is currently funded by INAC for elementary and secondary education; and

- be ordinarily resident on reserve.

With respect to CEC, INAC directly funds First Nations, Inuit and Innu CEC and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK).& INAC also funds the First Nations Confederacy of Cultural Education Centres who manages the funds and administration for a majority of First Nations CEC, through a Flexible Transfer Payment (FTP) funding authority.

1.2.4 Program Resources

In 2008-09, INAC's ESE and CEC programming received $1.2 billion in funding.

Education programming is funded through annual Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFA) and five-year Canada or DIAND/First Nations Funding Agreements (CFNFA/DFNFA). These arrangements include various funding authorities, notably, grants, contributions, FTPs and Alternative Funding Arrangements (AFA).

The allocation of program funding involves the distribution of funds from Headquarters (HQ) to the regions and from the regions to the recipients. The DFNFAs are formula-driven, and are consistent throughout the country. The CEC allocation model for the program, on the other hand, varies sometimes significantly by region. Findings from the 2009 Audit of Elementary and Secondary Education Programming found that this variance may be causing inequitable access to program funding.

In terms of the allocation of funds from HQ to the regions, program funding is a component of each region's annual core budget. The Education Branch does not determine the amount of program funding to be allocated to each region. This is the responsibility of the Resource Management Directorate in Finance at HQ. National budget increases (currently two percent annually) are allocated to each region in proportion to their existing budgets. The regions have the authority to allocate funds across the various programs included in their core budget and therefore, ultimately decide the extent of program funding to provide to their recipients.

An analysis of data in the First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment (FNITP) System was undertaken; however, was excluded from this study due to concerns with the completeness of the extracted reports, and will instead be thoroughly assessed for the summative evaluation to provide a clear analysis of expenditures.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined elementary and secondary education program activities, including instructional services for Band‑Operated Schools, Federal Schools and Provincial Schools; Elementary and Secondary Student Support ervices; New Paths for Education; Teacher Recruitment and Retention; and Parental and Community Engagement. It also included INAC's CEC Program, last evaluated in 2004. This evaluation provides information on relevance and, to the extent possible, performance, to support the management of program authorities in compliance with Section 6.5.3 in the Policy[Note 3] on Transfer Payments. In addition, it provides some preliminary information on the state of data collection in elementary/secondary programming, and facilitates the contextualizing and framing of questions for the summative evaluation in 2010-11. Terms of Reference were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 4, 2009. A contract for the implementation of key informant interviews was approved in November 2009, and a contract for the implementation of a literature review was approved in January 2010. Data collection and analysis was undertaken primarily between January and February 2010.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference, the evaluation focused on the following issues:

Relevance

- Continued Need

- To what extent are the intended outcomes of the program in line with the needs of First Nations students? Is the elementary/secondary program capable of meeting these needs?

- To what extent are the intended outcomes of the program in line with the needs of First Nations students? Is the elementary/secondary program capable of meeting these needs?

- Alignment with Government Priorities

- To what extent are the objectives of the elementary/secondary education program aligned with the Government of Canada's approach to First Nations education?

- To what extent are the objectives of the elementary/secondary education program aligned with the Government of Canada's approach to First Nations education?

- Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- Is this program still a priority of INAC and/or the federal government?

Effectiveness

- Performance

- To what extent is the elementary/secondary program achieving the intended outcomes?

- How are existing partnerships (e.g. with Other Government Departments, provinces and the private sector) benefitting or impacting First Nations schools, as well as education and skills development, more broadly?

- Have there been any unintended positive or negative impacts of the program?

- To what extent is the elementary/secondary program achieving the intended outcomes?

- Demonstrations of Efficiency and Economy

- Can the same amount of resources be used to produce better outcomes?

- Do the administrative systems and operational practices allow for the efficient delivery of the elementary/secondary program in a cost-effective manner?

- Can the same amount of resources be used to produce better outcomes?

Design and Delivery

- Design

- Does the program have clearly stated activities, outputs and outcomes? How and to what extent can these be measured?

- What is the program's reach and target? Is this clearly articulated in the program authorities?

- Are the roles and responsibilities of all parties well defined (i.e. INAC, Regional Management Organizations (RMOs)?

- Does the program have clearly stated activities, outputs and outcomes? How and to what extent can these be measured?

- Delivery

- Are the current funding instruments the most effective and efficient methods to manage the program?

- Are there any capacity issues for INAC and/or the RMO's or tribal/band councils regarding the administration and delivery of the program?

- Do other key challenges exist with respect to the administration and delivery of the program (for schools, RMOs or tribal/band councils, INAC regional offices, INAC HQ, etc)? If so, what are these challenges?

- Are the current funding instruments the most effective and efficient methods to manage the program?

Other Evaluation Issue(s)

- What recommendations, options, alternatives, possible strategies or changes should be considered to achieve the intended outcomes?

2.3 Evaluation Method

The following section describes the data collection methods used to perform the evaluation work, as well as the major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report.

2.3.1 Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following multiple lines of evidence (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix):

- Literature Review:

A literature review was conducted using national and international sources. This included, but was not limited to, Aboriginal-specific literature, academic journals, newspaper articles, reports from relevant national and international organizations, and federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) government websites. - Document and File Review:

A document and file review was undertaken and included Treasury Board Submissions, previous audits and evaluations, previous RMAF/Risk-based Audit Framework's, management plans, progress and performance reports, project files and other administrative data. - Data Analysis:

A review of the Nominal Roll database for fiscal years 2004-05 to 2008-09. However, as data were still being aggregated and analysed by the program at the time of writing the report, Nominal Roll data will not be included in the formative evaluation.

An analysis of Canadian Census data was further undertaken, as well as a statistical analysis of data from the Community Well-being Index, which is a composite index of census data measuring well-being in the areas of income, education, housing, and labour force activity.

Expenditure data were extracted using the FNITP System. Note, however, there were concerns with the completeness of the extract and thus, these data will be further vetted and reanalysed for reporting in the summative evaluation (see Section 2.3.2). - Key Informant Interviews:

A total of 23 interviewees (both INAC staff and key stakeholders) were interviewed to address formative questions (19 INAC, four First Nations). Key informants were selected based on their level of knowledge of education policies and programming, and/or their expertise in First Nations education issues.

2.3.2 Considerations and Limitations

The formative evaluation of Elementary/Secondary Education was largely administrative, and focused mainly on how INAC collects and uses data to determine the needs and outcomes of students. This is reflected in the number of interviewees, as well as the limited involvement of individuals and organizations outside INAC, including First Nations representatives. As the summative evaluation to be administered in 2010-11 will focus heavily on results, including achieved outcomes for students and First Nations communities, extensive involvement of First Nations organizations and other experts will be sought both in the design of the summative study and for inclusion as key informants.

Significant delays in getting the proper mechanisms in place to move the evaluation forward caused considerably tight timelines and impacted the extent to which information could be collected and examined. As a consequence, the response rate of First Nations representatives contacted for key informant interviews was extremely low for this study. Additionally, a full census of reports available through INAC's data systems was not obtainable, and thus, a sample of reports was pulled to examine the state of information flow and reporting. These constraints also hampered the resolve of data integrity issues with respect to examining program expenditures.

While it was originally anticipated that data would be analysed using Nominal Roll reports, there were significant data integrity concerns and an inability to analyse the data in a manner that could answer questions posed by this evaluation study. At the time of the writing of this formative evaluation, revised reports from Nominal Roll were being generated that will be included in the summative evaluation. Given that Nominal Roll is the most thorough element of data collection for elementary/secondary education and includes data on graduation and drop‑out, it contains very important information moving forward. It is, thus, critical to ensure these data are fully assessed for reliability and are accurately analysed before drawing conclusions from the information contained within the database.

In examining information on program expenditures, concerns were also raised about data integrity given some irregularities in the data. Data integrity concerns prevented the inclusion of expenditure data from FNITP in this report; and consequently, a more thorough examination of updated expenditure data is scheduled for the summative evaluation in 2010-11. Specifically, there were concerns with the accuracy and completeness of data contained in this particular extraction given the data were extracted using current coding mechanisms, and expenditures not coded under these would be missed. For example, coding for particular types of activities may be different depending on fiscal year or how the funding arrangement was designed. Therefore, the expenditure data analysed was likely not fully reflective of total expenditures by activity, year and region.

Of key concern in using data from the Canadian Census and the Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, is that data are only reflective of individuals measured at the time of the census. Additionally, there are a number of First Nation communities that do not participate in the Canadian Census. Thus, neither the Canadian Census nor the associated CWB data are able to account for individuals who complete or leave school and then leave the community and move to a non-First Nation community. The CWB Index also only includes communities with a population of greater than 65 people. It is also critical to note that the census indicator, and thus, the formula to calculate CWB score for education changed for the 2006 Census. Whereas the census prior to 2006 included data on functional literacy (those aged 15 or older with at least a grade 9 education) and those aged 20 or older with at least a high school education, the 2006 Census included data on this latter variable but not on functional literacy, and instead, on those aged 25 or older with at least a bachelor's degree. This is a critical consideration because the formula for CWB had to change accordingly and thus, the score prior to 2006 and the score for 2006 does not measure the same indicator. Analysis of CWB data between 1981 and 2006 shows a modest but steady increase in CWB score for First Nations communities up to 2001, and from 2001 to 2006, there is either a decline or levelling off of the CWB education score. Given that there is no theoretical explanation for this sudden change, it is highly probable that this is related to the change in methodology. Thus, data between 2006 and the other census years are not directly comparable.

Finally, given that there is a high tendency of youth to move off reserve and that First Nation populations are highly mobile[Note 4], results from both the Canadian Census and the CWB Index must be interpreted cautiously.

Key informants selected for this study were selected based on the recommendations of the Advisory Committee with respect to persons who would be most knowledgeable about INAC education programs and policies and First Nations education issues. Thus, the selection is inherently biased as no formal selection procedure was used. This issue will be mitigated in the summative evaluation with a formal selection procedure for key informants from First Nations.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of INAC's Audit and Evaluation Sector (AES) was the project authority for the Elementary/Secondary Education evaluation, and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process.

An Advisory Committee was established between INAC's EPMRB, ESDPP and the Assembly of First Nations, which considered both the Elementary/Secondary and Post-Secondary Education evaluations. The purpose of the Advisory Committee was to work collaboratively to produce evaluation products, which are reliable, useful and defendable to both internal and external stakeholders.

Furthermore, the evaluation team organized an internal peer review of the methodology report and held two validation sessions regarding technical reports.

A significant portion of the work for this evaluation was completed in-house. The consulting firm, TNS Canadian Facts was commissioned to conduct a review of documentation and to implement key informant interviews and Harvey McCue Consulting was commissioned to conduct a review of literature. Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The EPMRB evaluation team identified key documents, provided documentation, data for the study, and names and contact information of First Nations representatives and INAC resource persons at HQ and regional offices. The team further expeditiously reviewed, commented on and approved the products delivered by the contractors.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

The evaluation looked for evidence that the intended outcomes of elementary and secondary education programming at INAC are in line with the needs of First Nations students. It further looked at whether elementary and secondary education programming is consistent with government-wide and departmental priorities and roles and responsibilities.

Findings

There is a demonstration of continued need with respect to improving the rates of high school completion; addressing clear gaps between education inputs on reserve and among provincially‑operated schools; and addressing Aboriginal-specific learning needs, including culture and language.

The intent of elementary/secondary education programming is consistent with Government of Canada objectives of eliminating systemic barriers faced by Aboriginal populations and facilitating participation in the labour market and economic success. However, there is a lack of clarity with respect to roles and responsibilities and their alignment with program objectives; specifically, the delineation of roles and responsibilities with respect to program design and operation, and with respect to the principles of First Nations control of education.

3.1 Continued Need

In 2008-09, INAC invested $1.8 billion toward First Nations education, including $1.3 billion to support elementary and secondary education for approximately 120,000 First Nations students normally living on reserve.

According to key informants' general understanding of the program, the objectives of elementary/secondary programming are:

- To provide a provincially comparable education to students living on reserve;

- To improve student outcomes; and

- To improve graduation rates/reduce drop-out rates.

While there was little debate about the last point, key informant interviews revealed that what is meant by ‘provincially comparable education' and what it means to ‘improve student outcomes' for First Nations, they are not consistently understood among government and First Nations. In terms of provincially comparable education, three possible measures have been identified: funding; programming; and outcomes. From a funding perspective, in 1996, a two percent funding cap was placed on programs and services to First Nations, including education spending. Meanwhile, several provincial governments have invested a significant amount of funding into provincial education, well beyond a two percent annual increase. For example, total expenditures in public schools nationally increased at nearly twice the rate of inflation between 2000-01 and 2006-07. Specifically, expenditures increased 4.5 percent between 2005-06 and 2006-07, to $49.6 billion; and up 27.9 percent over the six-year period, while the rate of inflation over the same time period was 14.4 percent.

Add to this the rising cost of tuition, cost of living, transportation and teacher salaries, as well as inflation, there appears to be a disconnect with respect to comparable funding. Note that INAC's funding allocations and issues in determining costs will be further addressed under Section 5.1 – Design.

With regards to programming, the Education Branch's 2008 RMAF states that one of the objectives of elementary/secondary programming is to provide education programs that are comparable to those required in provincial schools by the statutes, regulations or policies of the province in which the reserve is located. While some standard programming is essential, such as numeracy and literacy, this approach clearly has the potential to overlook Aboriginal-specific approaches to learning, such as the necessity of Aboriginal culture and language to a child's identity and well-being, which was a significant gap in programming pointed out by both First Nations and non-First Nations interviewees. Additionally, the number and capacity of the centres' as well as their influence varies between regions and geographic zones.

In terms of outcomes, INAC has approached education programming much like other programming in the Department. This means that INAC has assumed the position of a funder and has given the control of education programming over to First Nations communities and organisations. In theory, this is respecting the principle of First Nations control of education. The reality, however, is that INAC still requires a large amount of reporting and has a statutory obligation for education under the Indian Act. In addition, without appropriate capacity and resources, many communities are unable to maximize the impact that First Nations control of education could have over something as fundamental as education of children.

Population growth trends and the key informants interviewed in this study suggest that the growth of Aboriginal populations will undoubtedly generate further need with respect to education. As stated in INAC's 2009-10 Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP),[Note 5] Canada's Aboriginal population is young and growing almost twice as fast as the country's general population (1.8 percent per year vs. 1.0 percent). INAC recognizes that this will affect the demand for education, among other programming, and that it will be essential to support students through skills training and education programming that is adapted to the unique circumstances (e.g. poor health, poverty, remote locations, cultural diversity) of First Nation communities.

For example, an analysis[Note 6] of CWB Index data suggests that, with the exception of Quebec, in the vast majority of cases, CWB education scores decreased the further away people lived from a service centre (according to geo-zone categories).[Note 7] For some regions, particularly Atlantic and British Columbia, this has become more pronounced over time. In most cases, the reason for this trend is the much higher CWB education scores in Zone 1 communities compared to Zones 2, 3 and 4. This is most apparent in Northwest Territories and in Quebec, where the CWB education score does not necessarily decrease with increasing distance across all geo-zones, but scores for Zone 1 communities are clearly higher than the rest, which are not very different from one another.

Further, when analysing CWB education scores in relation to Environmental Remoteness,[Note 8] the tendency towards poorer education scores with increasing distance to the North was less evident, though still present. This tendency, however, seems to be becoming more pronounced over time, particularly in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. Additionally, there was a tendency for communities classified as Environmental Remoteness B to have higher CWB education scores than all others (there were no Class A communities in the data). This data suggests that there is a clear need to address specific community circumstances through education programming. Analysis of CWB data is further discussed in Section 4.1 on impacts.

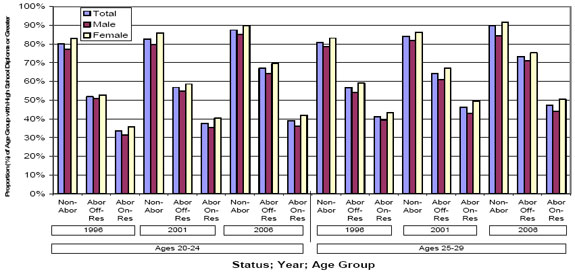

Differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations are also illustrated by Canadian Census data. As shown in Figure 1 below, the proportion of non-Aboriginal populations aged 20-29 with a high school diploma or higher has been consistently higher than Aboriginal populations both off and on reserve, and has increased approximately eight percent between 1996 and 2006. Additionally, while both non-Aboriginal populations and Aboriginal populations off reserve have shown noticeable increases over time, this has been much less pronounced for First Nations populations on reserve. Census results, however, must be interpreted with caution, as it is entirely possible that out-migration from on reserve communities may be biased toward those with a high school education or higher.

Census data also demonstrate a higher proportion of completion for women than men, which is a trend observed among both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities both on and off reserve. Further, one study identified in the literature suggested male students are far behind their female peers with respect to numeracy and reading skills. Further, the study suggested that gender differences were greater among Aboriginal students; particularly students attending band operated schools, although this is not substantiated by census data.

Figure 1: Proportion (%) of Age Groups with a High School Diploma or Higher by Gender by Type (non-Aboriginal; Aboriginal off reserve; Aboriginal on reserve[Note 9]), by Year, by Age Group of Interest[Note 10] (20-24; 25-29)

Source: Completed internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of Canadian Census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by type, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal Off-reserve and Aboriginal On-Reserve) by gender, year (1996, 2001 and 2006), and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 13% of the Non-Aboriginal population (11% of males and 16% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 3.5% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (3% males and 4% of females) and 1% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.5% of males and 1.5% of females).

In 2001, approximately 14% of the Non-Aboriginal population (11% of males and 17% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 4% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (3% males and 5% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

In 2006, approximately 18% of the Non-Aboriginal population (14% of males and 22% of females) aged 20-24 post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (4.5% males and 8% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 24.5% of the Non-Aboriginal population (22% of males and 27% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 6% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (5% males and 7% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2% of males and 4% of females).

In 2001, approximately 29% of the Non-Aboriginal population (25% of males and 33% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 9% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (7% males and 11% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2% of males and 4% of females).

In 2006, approximately 33% of the Non-Aboriginal population (28% of males and 38% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 13% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (9.5% males and 15.5% of females) and 4% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2.5% of males and 5.5% of females).

Mobility was also an issue identified in the literature as having impacts on student success, and therefore, as warranting consideration of the uniqueness of First Nations circumstances in determining needs. One research study suggested a correlation between frequent moves and the likelihood of quitting school for students aged 15-19.[Note 11] This has considerable implications, as there is research to suggest frequent school changes among Aboriginal youth are common.[Note 12] This is further illustrated in a study[Note 13] using a cohort of 4,500 students, wherein roughly 44 percent of them had changed schools between one and four times, and the completion rate was directly relational to the number of moves (once – 48.9 percent; twice – 28.1 percent; three times – 17.3 percent; and four times – 11.3 percent).

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

In the Government of Canada's annual report to Parliament, Canada's Performance – The Government of Canada's Contribution 2008-09, First Nations education falls under the outcome area "A Diverse Society That Promotes Linguistic Duality and Social Inclusion." According to the report, government efforts in this outcome area are intended to promote, among other things, the elimination of systemic barriers faced by Aboriginal Canadians and, specifically, First Nations education.

The need to improve First Nations education outcomes was also identified in Budget 2008. In this report, the Government of Canada committed to working with provincial governments, First Nations organizations and educators to develop new and more effective tools and approaches to First Nations education. Seventy million dollars was dedicated over two years to support tripartite agreements with willing First Nations and provinces. The focus of these agreements is to improve financial and performance management systems and implement community-based school success plans. Additionally, approximately $27.3 million was dedicated to support the development of the Education Information System (see Section 4.1.3).

Alignment of First Nations education with government priorities is also discussed in the 2009‑10 RPP, with the priority in First Nations education being to build a foundation for structural reform to improve education outcomes. The government's strategy for building this foundation is in line with what was outlined in Budget 2008, namely, to work with First Nations communities to help schools develop success plans, conduct learning assessments, develop performance measurement systems, and develop tripartite partnerships with First Nations communities and provinces. This is being reflected in the new Education Partnerships Program; an opt-in program for interested First Nations and provinces that supports the establishment and advancement of formal partnership arrangements that aim to develop practical working relationships between officials and educators in regional First Nation organizations and schools, and those in provincial systems. These partnership arrangements are meant to open the way to sharing information and better coordination between First Nation and provincial schools. It is, however, too early to report on any outcomes of this program.

A review of Government of Canada priorities suggests that improved First Nations educational attainment is the key to future participation in the labour market and economic success. According to the 2009-10 RPP, the benefits of this will be felt in First Nations communities and Canada at large through higher levels of self-esteem, well-being and participation in Canadian society.

Additionally, INAC, in partnership with the Inuit of Canada, as represented by ITK and other Inuit and public government bodies, signed the Inuit Education Accord in April 2009. The purpose of the accord is to establish a National Committee on Inuit Education that will work together to develop a strategy for moving forward on educational outcomes for Inuit students. With this initiative, the federal government has made a commitment to promote social and economic development in Inuit communities.[Note 14]

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The federal government obtained its legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians" under Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary school services to Indian children living on reserves.

INAC pays for education by funding band councils or other First Nations education authorities through several types of funding arrangements, namely, FTPs, AFAs, DFNFAs, and CECs. This funding pays for students normally resident on reserve to attend schools (whether the schools are on or off reserve); student support services, such as transportation, counselling, accommodation and financial assistance; and school administration and evaluation.

After the National Indian Brotherhood[Note 15] publication of Indian Control of Indian Education was released in 1972, the federal government accepted the principles of this policy and, in 1974, began funding band-operated schools. Since then, there has been uncertainty around the role of the federal government in First Nations education. In a 2000 report, the Auditor General reported that many INAC regional offices saw their role in First Nations education as funders.[Note 16] In response to the OAG report, the Standing Committee on Public Accounts (SCPA) expressed its concern regarding the lack of clear roles and responsibilities, stating that "the Department must clarify and formalise its role and responsibilities, otherwise, its accountability for results is weakened and assurances that education funding is being spent in an appropriate fashion are unclear at best."

In the 2004 follow-up to her 2000 report, the OAG expressed concern for "the Department's lack of progress in defining its roles and responsibilities" and went on to express that "until the Department clarifies these and its capacity to fulfill them, and reaches a consensus with other parties on their own roles and responsibilities, it will remain difficult to make progress in First Nations education and close the education gap."[Note 17] Though this was written in response to the Post-Secondary Education Program, it is also in line with what has been said of elementary/secondary programming as well.

Partly in response to the OAG's 2000 report, the Department established the Education Branch in 2004.& In the Branch's 2008 RMAF, it described its role as "being limited to providing funding to support the educational needs of those living on reserve." While some key informants argued that this makes sense in terms of maximizing First Nations control of education, others argue, like the OAG and the SCPA, that a lack of clarity around education policy from INAC muddles accountability, as well as allows for inequity of services to students (both between bands and between bands and the province) and ensures INAC's inability to measure outcomes at regional and national levels.

INAC's vision is a future in which First Nations, Inuit, Métis and northern communities are healthy, safe, self-sufficient and prosperous - a Canada where people make their own decisions, manage their own affairs and make strong contributions to the country as a whole. Education programming is essential to achieving this vision. Research indicates how education is the key to success both in terms of preserving and promoting First Nations culture and identity, as well as economic success. A recent report from the Canadian Council on Learning states that learning from—and about—culture, language and tradition is critical to the well-being of Aboriginal people. Indeed, the report finds that such activities play an important role in the daily lives of many Aboriginal learners and are commonplace in Aboriginal communities across Canada.[Note 18] Another report from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards states that an important portion of the employment rate gap can be attributed to lower educational attainment among the Aboriginal population than among the non-Aboriginal population. Aboriginal Canadians are much less likely than non-Aboriginal people to either earn a high school diploma or a post‑secondary certificate.[Note 19]

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

The evaluation looked for preliminary evidence that students are able to succeed at school, the extent to which this can be attributed to INAC's elementary/secondary programming, as well as whether INAC's administrative systems and operational practices allow for the efficient and cost-effective delivery of the elementary/secondary program.

Findings

While detailed analysis of resources was not available for the current study, key informants overwhelmingly indicated a lack of resources to achieve identified objectives such as provincial comparability. Interviewees and documents reviewed suggest First Nations education funding allocations are not based on current realities.

While data from the Nominal Roll, to be used in the summative evaluation, will provide a more complete picture of student results, Canadian Census data suggest there have been noticeable improvements among Aboriginal populations in educational attainment overall. However, further analysis of census data and its associated CWB Index suggest that such improvements are very modest or non-existent within First Nations communities on reserve.

4.1 Performance

4.1.1 Resources

While there was only a limited analysis of costs and expenditures for the current formative report, a more complete analysis of expenditures is scheduled for the summative evaluation where further expertise will be utilised to assist with the analysis and interpretation of expenditure data. Additionally, given the high variations in the expenditures of various programs over time and between regions, and the fact that these have not been tied systematically to reporting that is able to be easily extracted, significant analysis is needed for a meaningful understanding of program resources. This kind of analysis will also be required within each region given the high variation of funding allocations and education programming. Finally, while reports are provided to INAC by First Nations education funding recipients, the information contained in the reports is not rolled into a database available for extraction and analysis (see Section 5.1 for further discussion).

Most key informant interviewees suggested that funding was insufficient to provide for adequate programming. Concern was expressed regarding potential inequities between provincial and band-operated schools. Additionally, given the steady growth of the population of First Nations people, rising costs for teachers (especially considering the difficulty with recruitment and retention in remote areas), technological advances, increased cost of living as well as increasing program costs, concern was expressed that insufficient resources would result in the reduction of various capital projects (due to reallocation of funds) and education programming.

Most key informants indicated that the current funding approach is outdated and ineffective in that it misses crucial elements, including language and culture, technological advancements, student support needs, cooperative education, and the current realities of costs of teacher recruitment and retention. Many also suggested that the funding approach should be closer to that of provincial schools, where funding is based on actual costs. Additionally, the Auditor General's Report (2000) and INAC's Evaluation of Band-Operated and Federal Schools (2005) both indicated that the funding allocations were based on outdated information. There was no evidence in the current evaluation study of any current detailed analysis assessing the appropriateness of the current funding allocations. See Section 5.1 for further analysis of the funding allocations.

Recurrent throughout the literature was that funding is deficient for a range of areas, including education infrastructure, curriculum development, special education, and language programs (see White & Beavon (2009);[Note 20] Paquette & Smith (2001);[Note 21] and McCue (2006)[Note 22] for further discussion).

4.1.2 Capacity

Key informant interviewees indicated that the financial capacity does not currently exist to meet increases in demand. Additionally, the majority suggested that there is not currently capacity to meet needs with respect to student transportation, special needs education, attracting qualified teachers, and ensuring adequate infrastructure.

Unfortunately, data and reporting on these various issues are limited. For example, while data on teacher salaries and qualifications are collected, these data are not systematic or mined for extraction and analysis, and some are self-reported. While information currently collected on teaching staff includes salaries, gender, Aboriginal status and teacher experience, there is no information collected on benefits, nor is it indexed by cost of living or remoteness. In addition, the information is scanned and uploaded into a database. While this does make the information available to be viewed, it is almost impossible and very labour intensive to compile and analyse. To provide an adequate analysis of the current state of teacher incentives and qualifications, data on salaries and benefits would be required in a user-friendly format, and indexed by cost of living, remoteness, gender, Aboriginal status and teacher experience.

Generally speaking, capacity issues are directly linked to resource issues discussed above. Ultimately, with respect to capacity, INAC interviewees suggested that there needs to be increases in funding, a clear definition of "comparability," increased staffing, increased accountability, and a review of core funding to ensure it addresses student need and teacher retention. First Nations interviewees suggested that improved long-term planning, improved infrastructure, and a more appropriate funding approach were required.

Much of the literature reviewed focused on the need for expanding the educational infrastructure in First Nation education. In particular, the absence of second and third level educational support services[Note 23] was noted as a serious impediment to the effective delivery of education to First Nation communities and schools.[Note 24] Additionally, researchers highlighted the lack of an appropriate education infrastructure and the resultant high demands on individual First Nation communities to deliver education in an educational resources vacuum. Much of this literature went on to recommend the need to abolish the community-by-community responsibility in favour of larger aggregations, which could offer opportunities for economies of scale, the foundation for a broader educational infrastructure, and educational capacity, all of which are currently lacking under the existing education regime.[Note 25],[Note 26],[Note 27],[Note 28] Specifically, it was suggested in the literature that equating Indian control with local control of education has led to diseconomies of scale[Note 29] within the educational infrastructures, suggesting a need for aggregation of education infrastructures that are governed according to community interests and equipped with appropriate professional capacities. Further, it was recommended that what is required to achieve this is the creation of a First Nations – owned and controlled school system; and First Nations educational authorities and regional First Nations equivalents of education departments under First Nations control.

The summative evaluation will need to draw further analysis on defining capacity needs, including a thorough review of funding approaches and program design and their potential impacts on First Nations education capacity. Moreover, it will need to consider the state of First Nations education infrastructure, indexed teacher salaries and benefits, as well as an assessment of outcomes on teacher recruitment and retention strategies. While reporting does exist on some of these measures, it does not currently include a meaningful analysis of actual outcomes, and consequently, it appears data collected is not being utilised to its potential.

4.1.3 Student Results

Overall, it has been very difficult to assess the extent to which outcomes have been met by students. While the evaluation team's preliminary search in FNITP showed that a significant amount of reporting was being collected, much of the information gathered falls short of what is necessary for meaningful outcomes measurement (for example, number of students enrolled, number of graduates with no context). As has been reported in previous audits and evaluations, these reports do not provide the Department with a clear sense of how students are doing or whether their needs are being met. Documents reviewed and information from key informants suggest that there is a very inconsistent understanding within the Department as to what exactly is being reported, and that very little of it is being analysed or utilised for program or policy purposes by either regions or HQ. While some of this can certainly be attributed to a lack of human resources and turnover, there is also an issue of consistency in reporting (including a lack of understanding/guidance of how to complete reports, staff turnover, qualitative answers, electronic vs. paper forms, to name a few) that makes reports difficult to roll-up. This results in a lack of analysis to define trends within the program. From a policy perspective, this is particularly problematic, as decision makers are not able to obtain the information necessary to make informed decisions.

Currently, INAC is implementing the Education Information System, which is intended to streamline and better utilise information from reports; store data in a "mineable" format to allow for complete analysis; use information from other databases to provide context on meaningful outcomes measurement (i.e., socio-economic and school infrastructure data); and to enable timely reporting on results-based performance indicators to be developed in discussion with First Nations and other stakeholders. Additionally, the expectations are that this system will reduce and simplify data reporting burden; allow for data integrity measures throughout data collection; link financial information to program results; and provide timely reports on program management and performance measurement.

Currently, the key tool for reporting on student outcomes is the Nominal Roll database. However, at the time of this report, a revised summary of Nominal Roll data was underway through the program and unavailable for reporting in the formative evaluation. A full analysis of Nominal Roll data is scheduled for the summative evaluation in 2010-11 (see Section 5.1 for further discussion of Nominal Roll).

INAC has, however, compiled a compendium of INAC program data[Note 30] from various sources, including the Nominal Roll for education. This report shows school counts and student counts by school type (band-operated, federal, private, provincial), by year (1998-99 to 2007-08), level (elementary, secondary), and gender. It also reports drop-out rates (calculating students who were enrolled, then withdrew during the school year, and are of school age and living on reserve, but no longer attending school) by all of the above variables. One key highlight was that the drop-out rate was consistently lower in federal schools across the observed school years, averaging about 0.4 percent, while averaging above five percent in band-operated, provincial and private schools. It also showed that the graduation rate was much higher for students in private schools (ranging from approximately 40 percent to 75 percent across years) than in band-operated or provincial schools (averaging roughly 25 percent) and that it was somewhat higher for provincial schools (ranging from 30 percent to 40 percent) than band-operated schools.

It is important to note, however, that the numbers of enrolled students between each type of school are very different, and these comparisons do not take into consideration regional variations. Both of these issues could explain differences in the rates tabulated. Additionally, serious data integrity concerns have been raised with respect to the reliability of data in Nominal Roll reports, and thus, currently, these data cannot be used to draw meaningful conclusions. The detailed analysis of custom extracts from Nominal Roll to be included in the summative evaluation will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the Nominal Roll data, its limitations, and its potential usefulness.

An analysis of custom tables from Canadian Census data (see Figure 1 in Section 3.1) shows an obvious gap in high school or higher completion rates between non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal populations. However, while the proportion is very high, the rate of increase among non‑Aboriginal populations has been modest compared to Aboriginal populations off reserve. Specifically, among adults aged 20-24,[Note 31] the proportion of Aboriginal populations off reserve having completed high school or higher increased by nearly 15 percent between 1996 and 2006. A similar increase can be seen among Aboriginal populations off reserve among adults aged 25‑29. These trends, however, were not observed for First Nation populations on reserve. The proportion of the total population with a high school diploma or higher increased only slightly between 1996 and 2001 for adults aged 20-24 (approximately five percent), and no increase was observed between 2001 and 2006. This same trend was observed among adults aged 25-29. As stated in Section 3.1, while there is a slight statistical variance between men and women in terms of high school completion, these differences are consistent with Aboriginal populations off reserve, and of non-Aboriginal populations.

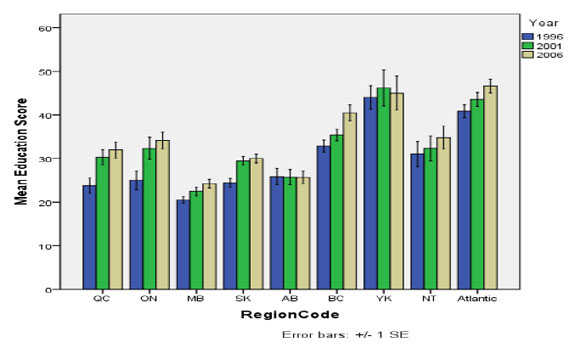

An analysis of CWB Index data further revealed that while there have been ncreases[Note 32] in CWB Education scores (see Figure 2) in most regions (with the exceptions of Alberta, Yukon and Northwest Territories), these increases have been modest compared to the average Canadian community increase (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Mean CWB Education Score for On Reserve Populations

by Region by Census Year

Source: Completed internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of CWB Index data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the First Nations mean CWB scores for Education by region and by year. Each region of comparison (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Atlantic) is represented by a cluster of bars with each bar in the cluster representing the year (1996, 2001 and 2006). The mean Education scores recorded for each region, named along the x axis, are indicated along the vertical y axis.

In Quebec, the mean Education score was approximately 24 in 1996, 30 in 2001 and 32 in 2006. The scores for Ontario were 25 in 1996, 32 in 2001 and 34 in 2006. In Manitoba, the scores were 21 in 1996, 23 in 2001 and 25 in 2006. In Saskatchewan, the scores were 25 in 1996, 29 in 2001 and 30 in 2006. In Alberta, the score was approximately 26 for all three years. The scores were 34 in 1996, 36 in 2001 and 42 in 2006 for British Columbia. The scores for Yukon were 44 in 1996, 46 in 2001 and 45 in 2006. In the Northwest Territories, the scores were 33 in 1996, 35 in 2001 and 40 in 2006. The Atlantic region's scores were 41 in 1996, 44 in 2001 and 47 in 2001.

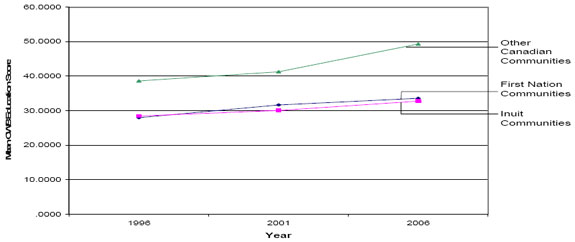

With the exception of Atlantic Canada, there appears to be a marked improvement in CWB Education scores for other Canadian communities, but little to no improvement for First Nations and Inuit communities. Generally, the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities is extremely wide and has not narrowed in recent years in any region; in fact, in some instances the gap appears to be widening.

Unfortunately, there are significant limitations to the data from the Canadian Census, given that they assess information from a community at a specific time, and thus, do not allow for the analysis of student outcomes, such as completion of high school, progression to post-secondary or labour force participation, and the high probability of out-migration after completing school. Additionally, as discussed in the limitations section above, the change in the formula used to calculate CWB Education score changed for the 2006 Census. Given the lower rates of completion of high school among First Nations onreserve relative to populations off reserve, removing from the formula a well-being indicator from information before the completion of high school would naturally be expected to moderate any increase in this score, or even decrease the score.

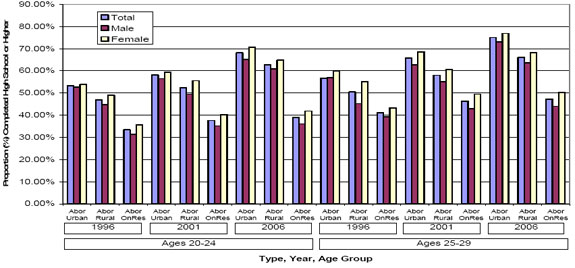

However, further analysis of census data reveals that when examining Aboriginal populations off reserve between persons in rural versus urban communities (see Figure 4), the proportion of people with a high school diploma or higher is greater among urban than rural communities. It further shows that both the proportion and the rate of improvement for both age groups are considerably higher for Aboriginal populations in rural communities than for First Nation populations on reserve. Also, as shown in Figure 5, while completion rates for non-Aboriginal populations are consistently higher than Aboriginal populations, the gap between urban and rural is roughly similar for both groups. These analyses suggest that rural isolation does not independently account for the lower completion rates seen among First Nation populations on reserve. It is entirely possible that either there are far lower completion rates among populations on reserve, or that the out-migration of people with high school or higher educations from reserves may account for this large discrepancy. However, without the ability to control for degree of isolation and latitude (which while indexed in CWB Index data, was not indexed with census data for this analysis), other mediating variables associated with being on reserve cannot be ruled out.

Figure 3: Mean CWB Scores Over Time Between First Nation Communities;

Inuit Communities and other Canadian Communities

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of CWB Index data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph indicating the mean Community Well Being (CWB) Education scores for Inuit, First Nations and Other Canadian Communities over the years 1996, 2001 and 2006, each represented by a separate line. The Mean CWB Education Scores are indicated along the y axis and the years are indicated along the x axis.

The graph illustrates that the CWB scores of Inuit were roughly the same as those of First Nations Communities, while remaining markedly lower than the scores of Other Canadian Communities.

According to the graph, the scores for Inuit Communities were approximately in 28 in 1996, 30 in 2001 and 33 in 2006; the scores for First Nations Communities were 27.5 in 1996, 32 in 2001 and 34 in 2006; and the scores for Other Canadian Communities were 38 in 1996, 41 in 2001 and 49 in 2006.

Figure 4: Proportion (%) of Age Groups with a High School Diploma or Higher by Gender by Type (Aboriginal Urban; Aboriginal Rural; Aboriginal On-reserve),

by Year, by Age Group (20-24; 25-29)

Source: Completed internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by status, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a type (Aboriginal Urban, Aboriginal Rural and Aboriginal On-reserve) by gender, total population, year (1996, 2001 and 2006) and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 3.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (3% of males and 4.5% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 3% of the Aboriginal Rural population (2.75% of males and 3.5% of females) and 0.75% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.5% of males and 1% of females).

In 2001, approximately 4.25% of the Aboriginal Urban population (3.25% of males and 5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 3% of the Aboriginal Rural population (1.75% of males and 4% of females) and 1.25% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.75% of males and 1.75% of females).

In 2006, approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (4% of males and 9% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 5.75% of the Aboriginal Rural population (4.25% of males and 7% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (5.75% of males and 7% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 4.25% of the Aboriginal Rural population (2.5% of males and 5.75% of females) and 2.25% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1.5% of males and 3% of females).

In 2001, approximately 9.75% of the Aboriginal Urban population (7.5% of males and 12% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 5.25% of the Aboriginal Rural population (3.5% of males and 7% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1.5% of males and 4.25% of females).

In 2006, approximately 13.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (10.25% of males and 16.5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 7.5% of the Aboriginal Rural population (5.5% of males and 9.75% of females) and 4% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2.5% of males and 5.5% of females).

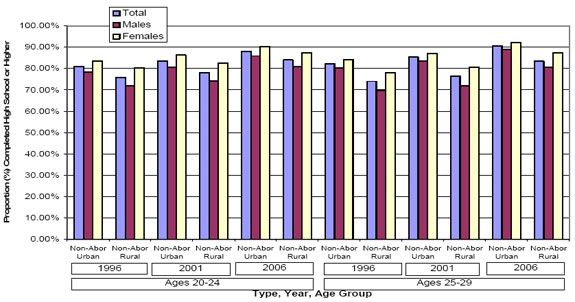

Figure 5: Proportion (%) of Age Groups with a High School Diploma or Higher by Gender by Type (Non-Aboriginal Urban; Non-Aboriginal Rural), by Year, by Age Group of Interest (20-24; 25-29)

Source: Completed internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by status, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a type (Non-Aboriginal Urban and Non-Aboriginal) by gender, by total population, year (1996, 2001 and 2006) and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 14.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (12% of males and 17% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 9% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (7% of males and 12% of females).

In 2001, approximately 14.75% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (11.5% of males and 18% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 9% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (6% of males and 12% of females).

In 2006, approximately 18% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (14% of males and 22% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 11.75% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (7.5% of males and 16% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 26.25% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (24.75% of males and 28% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 13.25% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (10.5% males and 16.25% of females).

In 2001, approximately 31% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (27% of males and 35% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 15% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (10% of males and 20% of females).

In 2006, approximately 35.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (30.5% of males and 40.5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 17.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (12% of males and 23% of females).

Figure 1 in Section 3.1 above also suggests that non-Aboriginal populations and Aboriginal populations off reserve are completing high school diplomas or higher at a younger age than First Nation populations on reserve. This is shown by larger increases in completion among populations on reserve from early 20's to late 20's than among populations off reserve and non‑Aboriginals.

While there is a clear gap between male and female rates of completion among Aboriginal populations both on and off reserve, this trend appears to be consistent with national trends among non-Aboriginal populations. This still suggests, however, that gender may require further consideration when assessing educational needs. For example, it is unknown whether the same factors are behind this difference on First Nations as among other populations; and therefore, this should be further investigated in the summative evaluation. Specifically, information should be sought from First Nations education representatives on gender differences within Aboriginal populations so that it can be analysed alongside research on gender differences in education success in Canada writ large.

It is also important to note that given that the funding envelope has remained relatively static over the past 15 years while education costs have steadily increased, any increase in graduation rates no matter how modest on reserve, indicates the ability at the local level to maximise resources; although there is no reporting to substantiate this.

A review of the literature revealed that a key theme is the lack of success in any country, United States, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, in the achievement of meaningful and positive educational outcomes among Aboriginal populations at the elementary-secondary levels. Each country continues to struggle with this issue and there is no evidence from the literature that any jurisdiction has a handle on dealing with the challenge. The results of the deficiencies at the elementary-secondary levels clearly impact negatively on the participation rates in post‑secondary.

4.2 Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy