Archived - Implementation Evaluation of INAC Climate Change Adaptation Program: Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: December 8, 2009

Project No.: 1570-07/09053

PDF Version (268 Kb, 52 Pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Climate Change Overview

- 3.0 Program Description

- 4.0 Methodology

- 5.0 Findings

- 6.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

Executive Summary

Introduction

This report provides the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the Implementation Evaluation of the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program (the Program), which forms part of the Adaptation Theme of the Clean Air Agenda (CAA).

The implementation evaluation examined the core issues of relevance and performance as outlined in the Treasury Board Secretariat's (TBS) new directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009), including the design, delivery, and accountability issues of the Program. Specifically, the evaluation focused on the design and implementation of the Program and its preliminary results/success since its inception in 2008–09. Environment Canada will use the findings of this evaluation, and a summative evaluation planned for 2010–11, to contribute to the reporting on the CAA's Adaptation Theme by fiscal year 2010–11.

The objectives of the Program are to assist northerners to:

- "Assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change; and

- Develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans to increase the capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to address the impacts of a changing climate."

To achieve these objectives, this three-year (2008–09 to 2010–11), $14 million Program awards contributions to departmental partners (territorial governments, non-governmental organizations, Aboriginal organizations, related federal departments such as Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), communities and other northern institutions, and associations) to help northern communities understand the impacts of climate change and take steps to adapt or respond to anticipated changes.

Methodology

A matrix of questions, indicators, and data sources guided the evaluation. Note that the research questions relating to the short-term results/success of the Program were drawn from the immediate and intermediate outcomes of the Adaptation Theme and the CAA in an effort to increase the compatibility of the present evaluation with future Theme- and Agenda-level evaluations.

The evaluation methodology comprised the following data collection tasks: document review, literature review, file review (n=37); key informant interviews (n=29); and a focus group (n=3). Limitations of the evaluation methodology included: the ability of the evaluation to measure outcomes, as the Program has only completed one funding cycle and many of the projects funded in the second cycle are just getting underway; the extent to which the Program increased awareness of climate change adaptation issues could not be determined because benchmark data on climate change awareness was not collected prior to the start of the Program; the file review was limited to identifying project activities and outputs that were likely to achieve outcomes as identified in project final reports (since these reports did not contain information on achieved outcomes); and case studies with program recipients were a planned line of evidence to demonstrate results, but a preliminary review of project files illustrated that this line of evidence was premature. Instead, a focus group was conducted to gather information on Northern regions' climate change adaptation progress.

The Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) contracted the consulting firm, Prairie Research Associates to help conduct the evaluation.

Findings, conclusions and recommendations

Key findings and conclusions from the evaluation are as follows:

Rationale/Relevance

The Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program is designed to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change and to enhance beneficial impacts. The Program is addressing northern climate change on northerners and adaptation needs by helping communities understand what efforts are being undertaken to address climate change and to determine how they can plan to adapt to these changes.

The evaluation found that the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program aligns well with the priorities of the federal government and INAC. The Government of Canada has a long history of involvement in climate change initiatives and remains committed to addressing climate change, including adaptation, as demonstrated by its CAA and its involvement in the International Polar Year, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the International Panel on Climate Change. The Program contributes to three of INAC's strategic outcomes: The North, The People, and The Land, and it builds on two former INAC programs: the Aboriginal and Northern Climate Change Program and the Aboriginal and Northern Community Action Plan.

The evaluation found that there is a continued need for climate change adaptation planning and implementation programming in the North. First, this three-year program does not have the capacity or resources to reach all of the communities in the North; consequently, there are some communities that have yet to engage in adaptation planning. Second, there is substantial evidence to suggest that most communities would likely cease adaptation planning if the Program was not available because no other climate change adaptation programs targeting the North exist and communities have a wide range of competing non-climate change-related priorities to address. Third, without continued support, communities are unlikely to implement their adaptation plans and, therefore, will revert to a reactive approach to adapting to the impacts of climate change. This issue will be further examined in the upcoming summative evaluation.

There is no evidence of duplication with other programs. No other formal climate change programs aimed at the North exist, and the Program works with other federal departments involved in climate change adaptation activities to ensure programs across government do not duplicate each other. As a result of the Program, projects have leveraged about $1.9 million in financial and in-kind resources.

Some complementary activities are occurring. Partially through support of the Program, the Yukon and Nunavut territorial governments are developing territory-wide climate change action plans. The Government of the Northwest Territories recently developed a climate change impact and adaptation report.[Note 1] While some northern communities are adapting to climate change without assistance from the Program, many of these adaptations are being implemented in reaction to specific climate change challenges and focus on behaviour change (e.g., taking extra care and caution while travelling, altering hunting practices, preparing for anticipated flooding).

Design and Delivery

All of the funded projects support the Program's objectives to assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change in specific communities, and to develop climate change adaptation plans. The second objective of the Program, however, suggests that it is intended to assist northerners to develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans. Much of the Program focuses on the development of adaptation planning. Most costs related to implementation (e.g., infrastructure and capital costs) are not eligible for funding as the Program does not have access to the financial resources needed to support implementation projects.

For the most part, the Program has been implemented as planned. The Program is funding projects that are designed to raise awareness of climate change, identify climate change risks and opportunities, generate new scientific knowledge, help build capacity to adapt to climate change, and begin work on developing adaptation plans. Key challenges encountered included the following:

- Establishing the adaptive capacity of communities and identifying key players with climate change adaptation mandates; and

- Working with internal services (e.g., on communications, contribution agreements, and human resources issues).

The Program has developed and implemented formal management structures such as an Operational Management Guide, Applicant Guide, and Technical Review Committee. However, some management and accountability deficiencies were encountered: some proposals do not clearly identify the activities, outputs, and outcomes associated with the current funding year; project reports do not include information on achieved outcomes; and the Advisory Committee has yet to be established.

The Program is attempting to measure performance. A project performance database is used to ensure diversity in type and location of projects; to identify projects' expected outcomes; to brief senior management; and to collect data for evaluations and program renewal. Nonetheless, a number of opportunities exist to improve the database (e.g., identifying which communities have been reached and which have completed adaptation plans).

Best practices include using a Technical Review Committee to review proposals; having people who will stay in the community to develop adaptation plans; having a project representative on the ground in the community; and obtaining letters of support for the project from the community.

Lessons learned are that programs should be built on equal partnerships; repeat messaging about climate change is needed; communities have many priorities other than climate change to address; jurisdictional barriers can make it difficult to conduct the research; adaptation takes time; and communities need additional resources to implement their adaptation plans.

Preliminary Results/Success

- Intended outcome: Greater collaboration to address issues of climate change

A wide range of stakeholders such as scientists, consultants, experts, and communities are collaborating on climate change adaptation projects. These collaborations have helped create a strong network of researchers and communities who are interested in climate change adaptation.

- Intended outcome: Increased availability of and access to information, technical expertise, and climate change adaptation products

Community awareness of climate change is increasing; however, the evaluation found that since baseline data was not collected prior to the start of the Program, it was difficult to assess the extent of increased awareness. There is considerable evidence that the Program brought technical expertise into northern communities and projects are developing climate change adaptation information that is accessible and relevant to these communities.

- Intended outcome: Northern communities and user groups are using tools and information to assess climate change risks/opportunities and to plan adaptation strategies

Communities are assessing climate change risks and opportunities and defining adaptation priorities. While projects are developing adaptation tools, there are no processes in place to track how they are being used.

The evaluation did not find evidence to support whether planning decisions are being based on identified risks and opportunities, or if climate change information or adaptation information is being integrated into planning and decision-making processes. This will be investigated further in the summative evaluation.

Alternatives

The evaluation found that this Program is the best approach to support climate change adaptation planning. The Program directly targets the North, has the flexibility to meet the needs of communities, involves communities in projects, and fosters the development of partnerships. However, the following are opportunities for Program enhancement: increasing program managers' presence in communities; establishing long-term, community-based positions that focus on climate change; increasing collaboration with other federal departments and territorial governments; strengthening relationships with INAC regional offices; coordinating the Program with the ecoENERGY Program; and providing multi-year funding for projects.

It is recommended that INAC:

- Conduct an environmental scan to:

- Determine the awareness of climate change and the capacity for adaptation planning in northern communities.

- Ensure that the Program targets communities in greatest need of support.

- Determine the awareness of climate change and the capacity for adaptation planning in northern communities.

- Clarify Program objectives:

- Develop a strategy that responds to the greatest need, allowing for transition through planning phases and into implementation.

- Develop a strategy that responds to the greatest need, allowing for transition through planning phases and into implementation.

- Continue to develop a website that can be used to:

- Facilitate the sharing of climate change adaptation information and tools.

- Extend Program reach.

- Facilitate the sharing of climate change adaptation information and tools.

- Identify and allocate specific resources to performance measurement to:

- Improve proposal review to ensure performance information is clearly articulated.

- Develop reporting template.

- Monitor project reporting requirements / ensure quality control.

- Strengthen and expand the performance tracking database.

- Manage the Program's performance measurement responsibilities (i.e., annual reporting).

- Improve proposal review to ensure performance information is clearly articulated.

- Increase Program efficiency and effectiveness by:

- Coordinating the Program with the ecoENERGY Program.

- Strengthening relationships with INAC regional offices.

- Establishing an Advisory Committee, which includes representatives of other federal departments, territorial governments, and communities.

- Providing multi-year support to projects.

- Coordinating the Program with the ecoENERGY Program.

Management Response / Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation and Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

1. INAC should conduct an environmental scan to:

|

|

Departmental Climate Change Coordinator & Manager, Adaptation | September 30, 2010 |

2. Clarify Program objectives:

|

|

Departmental Climate Change Coordinator & Manager, Adaptation | March 31, 2010 |

3. Continue to develop a website that can be used to:

|

|

Departmental Climate Change Coordinator & Manager, Adaptation | March 31, 2010 |

4. Identify and allocate specific resources for performance measurement to:

|

|

Departmental Climate Change Coordinator & Manager, Adaptation | March 31, 2010 |

5. Increase Program efficiency and effectiveness by:

|

|

Departmental Climate Change Coordinator & Manager, Adaptation | March 31, 2010 |

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan*

________________________________

Patrick Borbey

Assistant Deputy Minister

Date: _________________________

The Management Response and Action Plan for the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee December 7, 2009.

1.0 Introduction

This report provides the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the Implementation Evaluation of the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program (the Program), which forms part of the Adaptation Theme of the Clean Air Agenda (CAA).

The implementation evaluation examined the core issues of relevance and performance as outlined in the Treasury Board Secretariat's (TBS) new directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009), including the design, delivery, and accountability issues of the Program. Specifically, the evaluation focused on the design and implementation of the Program and its preliminary results/success since its inception in 2008–09. Environment Canada will use the findings of this evaluation, and a summative evaluation planned for 2010–11, to produce a thematic evaluation for the CAA's Adaptation Theme by fiscal year 2010–11.

The objectives of the Program are to assist northerners to:

- "Assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change, and

- Develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans to increase the capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to address the impacts of a changing climate."[Note 2]

To achieve these objectives, this three-year (2008–09 to 2010–11), $14 million Program awards contributions to departmental partners (territorial governments, non-governmental organizations, Aboriginal organizations, and related federal departments such as Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), communities and other northern institutions, and associations) to help northern communities understand the impacts of climate change and take steps to adapt or respond to anticipated changes.

1.1 Outline of the Report

Section 2, based on a literature review, provides the context for climate change adaptation planning and describes the Program. Section 3 defines the evaluation scope and outlines the evaluation methodology. Section 4 presents the evaluation findings in four subsections: rationale/relevance; design and delivery; preliminary results/success; and alternatives. Section 5 concludes the report and offers recommendations for consideration.

2.0 Climate Change Overview

This section, based on a literature review, provides an overview of climate change and the context within which the Program was established. It defines climate change, reports on the status of climate change in the North, describes the process of adapting to climate change, and identifies potential adaptation strategies.

2.1 Arctic most at risk

Climate change is a long-term shift in weather conditions including temperature, wind patterns, precipitation, and frequency/severity of storms.[Note 3] It may refer to increased climate averages (temperature, wind, precipitation) and increased variability in climate. While climate change has always occurred naturally, the preponderant view of scientists worldwide is that the world is experiencing changes in both rate and magnitude of weather conditions and global climate change. In part, this shift in climate patterns is believed to be a result of human activities such as land use changes and the combustion of fossil fuels, which have added substantial amounts of three common Greenhouse Gas (GHGs)—carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane—to the atmosphere. Human activities have increased and continue to increase concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere.[Note 4]

A natural system, the "greenhouse effect," regulates the temperature of the Earth. This system relies on the GHGs mentioned above and water vapour (another GHG) to trap the heat of the sun (like the glass of a greenhouse does), which maintains the Earth's average temperature at about 15°C, as opposed to the –18°C it would be without the greenhouse effect. Increasing the amount of GHGs in the atmosphere is presumed to enhance the ability of the greenhouse effect to warm the Earth, which in turn raises the average temperature of the Earth in what is commonly known as global warming.[Note 5]/[Note 6]

Many experts agree that Arctic regions are most at risk and will continue to undergo significant changes due to global warming.[Note 7] Many studies show that the Arctic has warmed significantly, and faster than the global mean over the last few decades, and will continue to get warmer in the future. For example, marine, terrestrial, and atmospheric studies synthesized by Serreze et al. (2000) indicated that "the climate of the Arctic has warmed significantly in the last 30 years."[Note 8] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that winter warming in the Arctic will be 40 percent greater than the global mean by the end of the century, and the temperature in the Arctic will rise approximately 3–4°C over the next 50 years.[Note 9]

2.2 Climate change impacts

Several changes to the physical and biological systems of the Arctic are being witnessed due to warming temperatures. It is predicted that these changes will continue and be more severe over the next century as the concentration of GHGs in the Earth's atmosphere continues to increase.[Note 10] These changes will also have social, economic, and cultural impacts on northerners.

Some of the documented physical climate change impacts are:

- Changing sea- ice thickness/melting and snow cover. The extent and thickness of sea ice and the extent of snow cover over land areas in the Arctic are decreasing. The melting sea ice and snow cover, along with shorter winters and the resulting shortening of the snow season, will continue to increase the impacts of climate change on the North. As the sea ice and snow melt, more of the ocean's dark blue water and the Arctic's dark terrain are exposed to absorb the heat from the sun, resulting in a faster warming Arctic.[Note 11] This is one of the reasons climate change impacts are expected to be greater in the Arctic than other areas of the world.

Melting sea ice and snow cover, along with melting glaciers, result in rising sea levels. It is predicted that by 2100, the melting of arctic glaciers alone will contribute four to six centimetres to global sea-level rise. It is expected that sea-level rise in the Arctic will "inundate marshes and coastal plains, accelerate beach erosion, exacerbate coastal flooding, and force salt water into bays, rivers, and ground-water."[Note 12] - Degrading permafrost. It is expected that over the next century, permafrost degradation will occur over 10 to 20 percent of the current permafrost area and the southern limit of permafrost will shift northward by several hundred kilometres. The thawing permafrost can have major impacts on infrastructure in the Arctic. Also, in combination with other climate change events, permafrost degradation can cause rockslides and avalanches.

- Warming temperatures. The warming temperatures in the North will increase evaporation, which will lead to increased rainfall. Much of the increased precipitation will appear in the winter months, which results in faster snowmelt and, when the rainfall is intense, can result in flash flooding in some regions.[Note 13] The amount of precipitation in the Arctic is predicted to increase by 20 percent by the end of the century.

The warming temperatures are also diminishing lake and river ice and are resulting in rising river flows. The shorter and warmer winters in the Arctic are causing later freeze up and earlier ice breakup of rivers and lakes, thereby causing peak river flows to occur earlier in the spring. - Increasing weather variability and severity. In general, Aboriginal communities in the Canadian Arctic have noted that weather has become less predictable and that storm events progress more quickly than they did in the past.[Note 14]

Some of the predicted biological impacts include:

- Shifts in vegetation zones. It is expected that climate change causes the boreal (northern) forests to shift into the Arctic tundra, and the tundra to shift into the polar deserts.[Note 15] The shrinking of the Arctic tundra and the polar deserts will result in major species shifts and possible extinction of endangered species that depend on these habitats.[Note 16]

- Decline in species. Species dependent on sea ice and the Arctic climate (e.g., polar bears, certain types of seals, walruses, and some marine birds) are at risk and likely to decline in numbers. If the sea ice continues to melt as predicted, some of these species may face extinction.[Note 17]

- Changes in fish populations. Fish populations may increase or decrease due to climate change. However, barring any major shifts, slightly warming temperatures may increase fish stocks, such as cod and herring, as higher temperatures and reduced ice cover could provide a more extensive habitat.[Note 18]

Examples of the social, economic, and cultural impacts of climate change on northerners include the following:

- Traditional land and resource use. The depletion and shift of species, shorter winters, and changes in snow and ice characteristics are making hunting more difficult and dangerous. Reduced snow accumulation and hard-packed snow caused by changing wind patterns makes it difficult for hunters to build igloos as temporary and emergency shelters.[Note 19] Unexpected storms and a lack of shelter have resulted in major injuries and deaths among northerners. Additionally, because many people in the Arctic often now live in permanent settlements, their ability to move with species as they shift locations is limited.[Note 20]

Northerners' land is susceptible to coastal erosion, which could result in the need for communities to incur costs to maintain buildings along the coastline and to develop measures for avoiding flooding, or to relocate further inland. For example, severe coastal erosion is already present in Tuktoyaktuk, Canada, leading the community to abandon an elementary school, houses, and other buildings.[Note 21] - Health. The melting sea ice has two key negative effects on human health in the Arctic. First, the risk of injury increases as hunters venture out onto the unstable ice. Second, melting sea ice may change the distribution of marine animals and fish, which could result in a change of diet for northerners. It has been noted that shifts to a more western diet increases risks of cancer, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease among Arctic populations.[Note 22]

Human health may also be affected by drinking water quality. Permafrost thawing, coastal erosion, extreme weather events such as floods and rockslides, and intense rainfall may affect the quality of drinking water, limit efficient delivery of water, or cause direct damage to water facilities.

Increases in injury, death, and disease from climate change are also related to weather events, such as extremes of temperature (both cold and heat) floods, storms, rockslides, avalanches, and intense rainfalls.

Severe psychological impacts can result from climate change in the North. Approximately half of the Arctic population have their culture, language, and identity tied to the land and sea of their Aboriginal heritage.[Note 23] This population will be forced to change their culture as the opportunities for subsistence hunting, fishing, herding, and gathering diminish. The inability of elders to predict weather and the loss of cemeteries and habitat from flooding, erosion, and permafrost thawing will also have severe impacts on their culture.[Note 24] These stresses have been associated with symptoms of psychosocial, mental, and social distress, such as alcohol abuse, violence, and suicide.[Note 25] - Infrastructure. The melting permafrost is expected to cause shifting in infrastructure such as buildings, industrial facilities, and pipelines. Since climate warming considerations were not incorporated in engineering designs and environmental impact assessments for infrastructure until the late 1990s, constant upgrades to existing infrastructure in the Arctic will be required to avoid structural failures.[Note 26]

- Transportation. In the winter, northern communities rely on ice roads for the delivery of groceries and other supplies. Once the ice roads melt, goods can only be delivered to certain areas by air or by water, which is much more costly. Ice roads are also very important for industry. Gas, mining, and oil industries use the ice roads to transport hundreds of tonnes of supplies to their sites each year, and for land exploration activities.

The melting permafrost will also have an effect on cement roads and railroads. As the layer of permafrost degrades, roads and railroads will shift, resulting in cracks and breaks. Therefore, continual maintenance of the roads and railroads will be necessary.

The melting and earlier breakup of the sea ice will, however, increase marine transport and access to resources. Extension of the navigation season will open up the possibility of more transportation in certain areas. It will also increase access to natural resources and may increase offshore extraction of oil and gas.

2.3 Adaptation strategies

Climate change is being addressed through mitigation and adaptation.

- Mitigation involves taking actions to reduce GHG emissions.

- Adaptation consists of initiatives and measures to decrease humans' and communities' vulnerability to the impacts of actual or expected climate change effects.

- Vulnerability is the degree that a community or ecosystem is susceptible to or can be harmed by adverse effects of climate change, and is determined by the adaptive capacity of communities to environmental changes.[Note 27]

- The adaptive capacity of a community is the extent to which it can address changes to its environment and depends on the following factors: wealth, technology, education, information, skills, infrastructure, access to resources, and management.[Note 28]

- Vulnerability is the degree that a community or ecosystem is susceptible to or can be harmed by adverse effects of climate change, and is determined by the adaptive capacity of communities to environmental changes.[Note 27]

The primary global response has been to address climate change through mitigation.[Note 29] Examples of mitigation methods include technological developments and awareness campaigns o try and control the level of GHG emissions released into the atmosphere.[Note 30/[Note 31] However, mitigation does not rapidly reverse climate change. Experts have confirmed that efforts to reduce GHG emissions have been slow and that it will take decades to stabilize climate change.[Note 32]

Adaptation, therefore, complements mitigation and is necessary to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change and to enhance beneficial impacts. daptation in the public policy context has been defined as "measures taken by any level of government […] to lessen the overall vulnerability of the public."[Note 33] Government easures ultimately fall into two categories: moral suasion and regulation. Moral suasion includes tools used by government to persuade the behaviour of populations without force. General policy tools include education programs and financial incentives. Regulation, on the other hand, forces populations to meet a particular standard. For example, a government could introduce a law that compels behavioural change.

Government can also choose to implement proactive, rather than reactive, climate change adaptation policies.

- Proactive policies develop adaptation methods in preparation for future climate change- related events. For example, enhancing adaptive capacity is a proactive approach because it prepares individuals and communities for expected future climate change events.

- Reactive policies implement methods for adapting to climate change following a major event. For example, bearing the costs and spreading or sharing the loss are reactive approaches because the effects of climate change are only being dealt with following a disturbance.

While a proactive approach is initially more costly to government and requires foresight, Warren et al. (2004) and Budreau and McBean (2007) agree that it is more beneficial than a reactive approach.[Note 34] Firstly, the proactive approach develops adaptive capacity because it prepares for future circumstances and incorporates long- and short-term climate change adaptation goals. However, the reactive approach only offers short-term solutions and does not develop adaptive capacity. Secondly, in the long run, it is predicted that proactive adaptation methods will be more cost-effective. Nonetheless, a combination of reactive and proactive approaches is most likely required in any community.

The drivers of adaptation are mainly economic development and poverty alleviation; therefore, they are already embedded in broader development, sectoral, regional, and local planning initiatives.[Note 35] The integration of adaptation strategies with economic and sustainable development initiatives is a useful option for territorial, provincial, national, and international governments to leverage funding from multiple sources and to align adaptation with broader governmental goals.

A review of the literature on climate change impacts on the physical and biological systems in the North, as well as the social, economic, and cultural impacts on northerners, clearly demonstrates a need for the Program and the rationale for why it was established. The following section describes the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program.

3.0 Program Description

This section identifies Program objectives and intended outcomes; reviews the Program theory; outlines the financial resources available to the Program; describes the governance structure and funding application and review processes; and outlines recipient reporting requirements.

3.1 Program objectives and intended outcomes

As previously mentioned, the objectives of the Program are to assist northerners to:

- "Assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change; and

- Develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans to increase the capacity of Aboriginal and northern communities to address he impacts of a changing climate."[Note 36]

However, as discussed in Section 5.1.1, the Program's main objective is to assist communities with adaptation planning. The Program does not have sufficient resources to fund the implementation of adaptation plans and therefore has not engaged in any activity in this area.

The Program's intended outcomes are listed in Table 1.

| Timing | Intended outcomes |

|---|---|

| Long-term outcome |

|

| Intermediate outcomes |

|

| Immediate outcomes |

|

| Source: INAC, 2008 (February). Climate Change Adaptation for Aboriginal and Northern Communities Initiative. Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk Based Audit Framework. | |

3.2 Resources

TBS allocated the Program $14 million in funding over the three-year period 2008-09 to 2010 11. The Program's planned expenditures for each fiscal year were: $4.7 million in 2008 09, $4.8 million in 2009-2010, and $4.5 million in 2010-2011. Section 5.2.1 compares planned and actual expenditures.

3.3 Governance

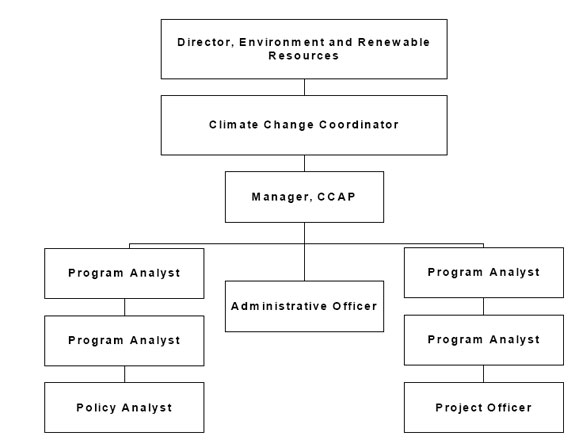

The Program fits into INAC program architecture within the Environment and Renewable Resources Directorate (ERR). Figure 1 illustrates the full organizational structure of the Program.

Figure 1

Organizational Structure

This chart shows the reporting relationships and organizational structure that the Assist Northerners program operates within. The chart shows three levels of management descending vertically including the Director, Environment and Renewable Resources; Climate Change Coordinator; and Manager, Climate Change Adaptation Program (CCAP).

Two arms extending below the program manager tier include a total of six program officer positions. The left arm contains two Program Analyst positions and one Policy Analyst position. The right arm shows two Program Analysts and one Project Officer.

Finally, an Administrative Officer position lies in the centre of the diagram, indicating that this position provides managerial and other office support.

Director, ERR. The Director, ERR, is responsible for the overall strategic management of the Program[Note 37].

Climate Change Coordinator. Operating immediately under the Director, ERR, the Climate Change Coordinator holds responsibility for ensuring that the Program is aligned with corporate policies within the INAC mandate and for being a point of formal contact between Program staff and the Director, ERR.[Note 38]

Program Staff. Program staff are responsible for the day-to-day operations of the Program including assisting proponents with proposals, participating in the Project Technical Committee, monitoring project implementation, and providing support to recipients. Additionally, INAC regional staff are involved in liaising with project applicants and recipients and assisting in the establishment of funding agreements with local project representatives.[Note 39]

Committees. The Program committed to develop the following two committees:

Project Technical Committee. The role of the Project Technical Committee is to review project applications and to make funding recommendations to the Director, ERR. The Committee is to appraise project proposals for feasibility and the degree to which they meet funding eligibility criteria.[Note 40] This Committee is functional (see Section 5.2.3).

Program Advisory Committee. The Program Advisory Committee is to be composed of various regional stakeholders, northern organizations, territorial governments, and other federal departments involved in climate change adaptation. The Committee is charged with reviewing the objectives of the Program, discussing the continued relevance of these objectives, and providing advice to the Program on the overall direction of operations and policy.[Note 41] This Committee has yet to be established (see Section 5.2.3).

3.4 Application Requirements and Process

The Program funds projects that:

- "Assess the risks and vulnerabilities to Aboriginal and northern communities related to the impacts of climate change;

- Support the preparation of action plans focusing on economic, social, cultural, environmental, and security issues;

- Address major issues related to climate change, such as:

- Emergency management and food security,

- Integration of climate change impact considerations into land use and community planning processes,

- Vulnerability of community infrastructure and of industrial and resource sectors,

- Development of adaptation management options, and

- Taking into account long-term changes to major project lifecycles; and

- Emergency management and food security,

- Result in specific tangible adaptation measures to address critical community issues such as storm surges and coastal erosion."[Note 42]

It should be noted that project funding is strictly confined to assessment, feasibility, and/or other types of research-based endeavours. The Program does not provide funding for infrastructure development, renewable energy or energy efficiency, capital development, political advocacy on climate change, or international adaptation initiatives and events.[Note 43]

The Program aims to provide project funding to any organizations, institutions, communities, and individuals who provide a project proposal that is well-matched to the objectives of the Program (see Section 3.1). It does not confine project funding to northern-based recipients; any group that shows a commitment to identifying risks related to the impacts of climate change in the North and/or to increasing capacity to address the impacts of a changing climate in the North can be considered as a potential Program recipient.[Note 44]

Proposals are to be funded according to a template included in the Applicant Guide and should contain the following information:

- Project title;

- Proponent, project coordinator, and contact partners;

- Background and rationale for the project;

- Project description;

- Objectives;

- Methodology;

- Community engagement;

- Work plan;

- Deliverables;

- Funding breakdown, including INAC and other sources; and

- Funding partners, indicating whether the contribution is cash or in-kind.

The primary consideration made during proposal review is the perceived strength of a linkage between the proposed project and the Program's Guiding Principles, which are:

- "Recognition that climate change impact intensity and form will vary by region;

- Recognition that communities and individuals are the essence of the projects;

- Contribution to managing risk related to climate change for individuals and communities in order to maintain safe and sustainable communities for all individuals;

- Developing the capacity at the community/organization level to increase the overall adaptive capacity of communities;

- Contribution to developing a strong information base integrating science, engineering practices, socioeconomic development, and traditional knowledge, to promote sustainable communities; and

- Using a partnership approach, building on regional and national initiatives, and leveraging tools, knowledge and funding as available."[Note 45]

The Project Technical Committee (as discussed in Section 5.2.3) conducts a subjective review of proposals based on the following criteria:

- "Eligibility of the applicant and the initiative according to the Guiding Principles;

- The project team has the capacity and expertise to conduct the project;

- The objectives of the project are consistent with Program objectives and priorities;

- The methodology clearly demonstrates how the proponents will address the objectives of the project;

- The proposal includes community involvement and engagement throughout the process; and

- The community and other communities can benefit from the project (directly or from lessons learned)."[Note 46]

3.5 Program recipient reporting requirements

Each funded project is managed under the conditions of TBS's Policy on Transfer Payments as well as INAC's own financial policies and procedures. All project funding is dispersed through a contribution agreement that details TBS and INAC funding criteria and basic project expectations and conditions. Contribution agreements are made for a maximum period of one year and a maximum amount of $200,000, although funding recipients may reapply annually. If agreements have been previously negotiated with INAC, exceptions can be made to fund projects beyond the $200,000 limit (for example, to cover the cost of travelling to the North).[Note 47] Upon project completion, Program recipients are required to submit detailed financial and program reports.

- Financial reports are required to outline project expenditures and funding from all sources during the project life cycle.[Note 48]

- Program reports are required to outline the findings and outcomes of the project work, and to detail the processes by which these outcomes were achieved. The Program reviews these reports at three different levels: first, by the Program Manager; second, by the Climate Change Coordinator; and finally, by the Director, ERR.[Note 49]

4.0 Methodology

This section outlines the evaluation methodology. It describes the data collection tasks and identifies the limitations of the methodology.

4.1 Evaluation objectives and scope

The implementation evaluation examined the core issues of relevance and performance as outlined in the TBS new directive on the evaluation function (effective April 2009), including the design, delivery, and accountability issues of the Program. Specifically, the evaluation focused on the design and implementation of the Program and its preliminary results/success since its inception in 2008–09. The Terms of Reference for this implementation evaluation were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee in April 2009. Field work was completed between July 2009 and October 2009

A matrix of questions, indicators, and data sources guided the evaluation. The matrix addresses four evaluation issues: rationale/relevance, design and delivery, preliminary results/success, and alternatives. The evaluation findings (see section 5) are organized according to these issues. The evaluation questions associated with each issue are listed at the start of each of the findings sub‑sections (Sections 5.1 to 5.4).

Note that the research questions in the evaluation matrix that relate to the short-term results/success of the Program were drawn from the immediate and intermediate outcomes of the Adaptation Theme and the CAA in an effort to increase the compatibility of the present evaluation with future Theme- and Agenda-level evaluations. This was accomplished by integrating the immediate and intermediate outcomes for the present Program as indicators for these higher-level outcomes. In most cases, the language of the outcomes at the Theme and Agenda levels were closely related with those of the Program. The main difference taken into consideration during the integration of outcomes was capacity building at the Adaptation Theme level, which was identified as an ultimate outcome for the Program, and was therefore excluded from this implementation evaluation.

A summative evaluation, planned for 2010–11, will gather additional evidence on the results.

4.2 Data Collection Tasks

The evaluation methodology included the following data collection tasks: document review, literature review, file review, key informant interviews, and a focus group. A technical report was prepared following the completion of each task. The evaluation findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of these multiple lines of evidence. INAC contracted the consulting firm, Prairie Research Associates to help conduct the evaluation.

4.2.1 Document review

A profile of the Program was prepared based on a review of documents provided by the Program, such as Treasury Board Submissions, the Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework (RMAF-RBAF), the Operational Management Guide, and the Applicant Guide. The information contained in the Program Profile provided the necessary background for the completion of the other evaluation tasks.

4.2.2 Literature review

The literature review included an initial scan of the relevant literature followed by the selection of key articles from the initial scan references. A scan of Canadian federal government, other countries', and international organizations' climate change initiatives concluded the search.

The literature review gathered evidence related to the rationale/relevance of the Program. The literature review report provides an overview of what climate change is, identifies the impacts of climate change on northerners, describes the process of adapting to climate change in the North, and reviews some of the adaptation strategies that are being implemented.

4.2.3 File Review

The file review provided a profile of the projects funded in 2008–09 and 2009–10, and described the progress the Program made toward its intended outcomes. It was based on the following information sources:

- Individual project files, which include the proposal, funding approval letter, contribution agreement, progress reports, final reports, and financial reports.

- The Program's performance tracking spreadsheet. This spreadsheet records project-level financial information and uses indicators to measure progress against activities, outputs, and outcomes. This spreadsheet is up-to-date for 2008–09 projects but not for 2009–10 projects as they are currently underway.

- The Program's project tracking spreadsheet, which collects information about proposal submissions, funded proposals, funding arrangements, and amendments. This spreadsheet was put in place for the 2009–10 funding year.

A total of 37 projects were included in the file review, including 19 projects[Note 50] funded in 2008–09 (which have been completed) and 18 projects funded in 2009–10[Note 51] (which are just getting underway).

4.2.4 Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews gathered respondents' perspectives on the Program's relevance, design and implementation, and progress to date.

Using a list of potential key informants provided by INAC, interviews were completed with 29 representatives from the following groups:

- INAC senior management (n=1)

- INAC representatives (n=7)

- Representatives of other federal government departments (n=3)

- Program recipients (n=18)

Key informants were emailed an introductory letter describing the objectives of the evaluation and explaining that they may be contacted for an interview.

Interviews were conducted over the phone, in the key informant's preferred official language. Prior to the interview, key informants received a copy of the interview guide so that they could provide considered responses. Separate interview guides were prepared for each type of key informant. A four-member Evaluation Advisory Committee, comprised of extensive climate change adaptation and experience and representing regions North and South of 600, reviewed and provided feedback on the draft interview guides.

Key informants were assured of the anonymity of their responses. To ensure accuracy, the interviews were audio-recorded (with the respondents' permission), then destroyed once the interview notes were completed.

4.2.5 Focus Group

The four members of the Evaluation Advisory Committee, who provided feedback on the draft interview guides, were invited to participate in the focus group. These individuals have extensive climate change adaptation knowledge and experience. Three of the invitees participated.

The one-hour focus group was conducted via teleconference. Participants received a copy of the discussion questions prior to the teleconference so they could prepare considered responses. The discussion centred on participants' perspectives on climate change impacts and risks, the capacity of northerners to adapt to climate change and progress made to date, and the next steps that INAC should take in supporting communities adaptation efforts.

4.3 Limitations of the Evaluation Methodology

The following are limitations associated with the evaluation methodology:

- The ability of the evaluation to measure outcomes is limited as the Program has only completed one funding cycle and many of the projects funded in the second cycle are just getting underway. However, a summative evaluation planned for 2010–11 will gather additional evidence on intended outcomes.

- Benchmark data on climate change awareness was not collected prior to the start of the Program; therefore, the evaluation could not determine the extent to which the Program increased awareness of climate change adaptation issues.

- The file review determined that project final reports did not include information on the achievement of outcomes. Therefore, the file review had to focus on identifying project activities and outputs that were likely to achieve outcomes.

- Case studies with Program recipients were a planned line of evidence to demonstrate results. However, a preliminary review of project files illustrated that this line of evidence was premature. Therefore, to gather general information on communities' adaptation progress, a focus group was conducted.

4.4 Analysis

The evaluation findings included in Section 5 are based on triangulation of all of the lines of evidence. As described in Section 4.2, the lines of evidence include a document review, a literature review, a file review, key informant interviews, and a focus group.

The strength of the support for the findings presented is assessed as:

- Substantial – all lines of evidence provide strong support for the finding;

- Considerable – most lines of evidence provide some support for the finding; and

- Some – few lines of evidence support the finding and/or there is limited support for the finding.

The findings section is divided into four subsections: rationale/relevance, design and delivery, preliminary results/success, and alternatives. The headings within each section provide a high‑level response to the evaluation question being addressed. The findings presented reveal the analysis of multiple lines of evidence; individual lines of evidence are only identified where notable.

5.0 Findings

This section provides the evaluation findings, which are divided into the following four subsections: rationale/relevance; design and delivery; preliminary results/success; and alternatives.

5.1 Rationale/Relevance

This section provides the findings relating to the rationale/relevance of the Program. It discusses the continued need for the Program, its alignment with government priorities, and whether it duplicates or overlaps with other programs.

5.1.1 The Program is relevant to northerners and addresses the continued need to adapt to climate change

This section responds to the following evaluation question: Is the Program addressing key environmental climate change needs? Is it relevant to the needs of northerners?

The Program is addressing northern climate change and adaptation needs

The evaluation found substantial evidence that the Program is addressing key environmental climate change needs and is relevant to the needs of northerners. Key informants reported that one of the strengths of the Program, and one of the factors that ensures it is relevant to northerners, is that it involves communities in climate change adaptation and encourages their ownership of projects. The Program is responsive to the needs of communities because the eligibility criteria (see Section 3.4) does not specify which climate change risks projects should address (see Section 2.1 for an overview of climate change impacts on the North); rather, communities have the freedom to define the climate change priorities that their project will focus on. This flexibility is further reflected in the level of effort that Program staff put into working with proponents to ensure their proposals meet the Program requirements as well as the needs of their community, which has resulted in only one proposal being rejected.

The evaluation also found substantial evidence that the Program is helping communities understand what efforts are being undertaken to address climate change and to determine how they can plan to adapt to these changes. The Program is funding projects in each of the territories as well as South of 60º. Based on the file review, the Program funded 37 projects, including 19 in 2008–09 and 18 in 2009–10. However, some projects received two phases of funding in a single fiscal year and some received funding in each of the Program's first two funding cycles. Table 2 below shows the distribution of projects across each region and funding year.

| Region | 2008–09 | 2009–10 (as of June 16/09) | Total | *Number multi-year projects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nunavut | 3 | 5 | 8 | 3 |

| Northwest Territories | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Yukon | 6 | 6 | 12 | 3 |

| South of 60º | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 |

| Other[Note 52] | 3 | - | 3 | - |

| Total | 19 | 18 | 37 | 10 |

| *This column indicates how many multi-year projects were funded. | ||||

Through funded projects, communities are increasing their capacity to understand the risks associated with climate change and to undertake a systematic assessment of, and formulate a coordinated and proactive response to, the vulnerabilities and opportunities associated with climate change. They are accomplishing this by conducting literature reviews, scientific research, risk assessments, and workshops. The following are some examples, from the file review, of the work being conducted through the Program:

- Nunavut. Most of the projects funded in Nunavut support the territory's Climate Change Strategy, one component of which is the development of a Nunavut Climate Change Adaptation Plan. Three partners have received funding through this Program to support the development of an adaptation plan for the territory. Examples of activities undertaken include visiting communities, holding community workshops, conducting literature reviews, training research coordinators, and conducting scientific research. Some of the outputs produced include a research report (Climate Change Priority Issues in Nunavut), a draft Coordinators Manual for the Ittaq Heritage and Research Centre, scientific data sets and reports, and community posters. Outcomes achieved include generating new knowledge about adapting to climate change, engaging communities in climate change adaptation planning, beginning to develop adaptation tools, and beginning to prepare adaptation plans for five pilot communities.

- Northwest Territories. Some of the projects in the Northwest Territories support the northern chapter of the national assessment of climate change and adaptation, From Impacts to Adaptation: Canada in a Changing Climate. Activities undertaken through this Program include visiting communities to promote climate change programming, conducting climate change workshops, and assessing climate change risks/opportunities relating to infrastructure and water, reviewing literature on climate change vulnerability and adaptation, and interviewing community members. Outputs generated include community climate change planning posters, notes on public information meetings, a report entitled Navigating the Waters of Change, and a report on gaps in adaptation and vulnerability literature. Outcomes achieved through these projects include raising awareness of climate change in northern communities, engaging communities in the adaptation process, generating new information for use in adaptation plans, and beginning to prepare pilot adaptation plans in two communities. Another project builds on general community sustainability planning efforts and a previous climate change‑related workshop.

- Yukon. Projects in Yukon also build on previous work including climate change-related workshops, risk assessments, vulnerability studies, and the northern chapter of the national assessment of climate change and adaptation, From Impacts to Adaptation: Canada in a Changing Climate. Activities undertaken include holding a workshop to communicate the importance of adaptation, developing a risk assessment workshop, preparing a work plan for community outreach, and conducting preliminary work to support the eventual development of regional climate change scenarios, and reviewing forest management and ecology to determine the impacts of climate change. Outputs of these projects include a workshop report, a workshop agenda and materials, publication of research results and preparation of an outreach plan, and collection of preliminary archival data. Outcomes of these projects achieved include strengthened partnerships, the generation of new information for use in adaptation plans, increased community awareness of climate change, and increased community capacity to engage in adaptation planning.

- South of 60º. Two of the South of 60º projects continue with previous work. One of them builds on the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources report, Climate Change and First Nations South of 60º: Impacts, Adaptations and Priorities, assessing the adaptive capacity of First Nation communities. The other builds on work that the Nunatsiavut Government completed, and continued the dialogue on climate change adaptation planning and built community capacity. Activities completed through these projects include a literature review, an environmental scan, the creation of a literature and knowledge database, and key informant interviews. Outputs include final reports. Outcomes achieved include strengthened partnerships, the generation of new information for use in adaptation plans, and increased community awareness of climate change.

Continued support for adaptation is needed

The evaluation also confirmed there is a continued need for adaptation in the North, to reduce the adverse impacts of climate change, and to enhance beneficial impacts. Key informants reported that communities would cease adaptation planning if the Program was not available. Partly, this is because no other climate change adaptation programs targeted at the North exist (see Section 5.1.3). However, as documented in the literature and raised by key informants, it also reflects the wide range of priorities communities must address, including the environment (e.g., contaminants), community infrastructure, pipelines, and social issues (i.e., housing, food security, and poverty). According to the literature, the ability of communities to adapt to climate change without support is limited by their high reliance on natural resources, poverty, inadequate safety nets, and limited financial resources to undertake projects.[Note 53] Budreau and McBean (2007) argue that government intervention is necessary to assist with these limitations.[Note 54]

The evaluation also demonstrated that a three-year program cannot address all of the adaptation needs in the North. Although the Program has been successful in reaching several communities, as is discussed in Section 5.2.1, and many Program recipients have participated in previous INAC programs, some communities are just becoming aware of climate change-related issues and have not had the opportunity to participate in adaptation planning activities as the Program is just starting to build momentum. Moreover, adaptation planning is a long-term process that involves multiple phases, as follows:

- Raising awareness of climate change;

- Identifying climate change risks/opportunities;

- Developing the capacity to address climate change; and

- Establishing adaptation plans.

As such, some communities will require multiple years of funding to complete their adaptation plans. Further, the evaluation found substantial evidence that communities are unlikely to implement their adaptation plans without access to additional resources.

The following is typical in developing climate change adaptation strategies:

Assessment of community vulnerabilities/adaptive capacity → Development of an adaptation plan → Implementation of sector-specific adaptation actions.

Although the Program's objectives and eligibility criteria suggest that funding can be used for some implementation activities (excluding infrastructure development, renewable energy or energy efficiency and capital development), Program staff indicated that the Program recognizes that it does not have sufficient financial resources to support this activity. Therefore, the current Program is addressing the first two items only, in the adaptation strategy.

Some key informants indicated that if the Program is not continued, this would signal to communities that climate change is no longer a priority issue for the Government of Canada, which may discourage communities from proactively adapting to climate change. They also suggested that gaps in programming will likely result in the need to redo work due to lost momentum, and the turnover in community members actively engaged in responding to climate change challenges.

5.1.2 Program aligns well with government priorities

This section responds to the following evaluation question: Is the Program aligned with federal government priorities and INAC priorities?

The evaluation found that the Program aligns well with the priorities of the federal government and INAC.

Alignment with federal government priorities

The Government of Canada has a long history of involvement in climate change initiatives and remains committed to addressing climate change today. The following are some of the Government of Canada's current climate change-related activities:

- The Clean Air Agenda (CAA). CAA represents Canada's continued commitment to addressing climate change. It forms the Government of Canada's response to improve the environment by reducing air pollution and GHGs. The CAA includes program measures to address actions in key areas, including adaptation. Programs under the Adaptation Theme seek to increase the resiliency and capacity of Canadians to reduce their vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

By funding adaptation-related projects, the Program aims to increase the capacity of northerners to adapt to climate change impacts. This outcome supports the CAA's long‑term outcome to reduce risks to communities, infrastructure, and the health and safety of Canadians resulting from climate change. It also supports the intermediate outcome of Canadians and communities taking action to reduce their vulnerabilities from and adapt to predicted impacts of climate change.

- International Polar Year (IPY). The Canadian government dedicated $150 million to Canadian science and research projects as part of IPY 2007–2008, which was "the largest-ever international program of scientific research focused on the Arctic and Antarctic regions."[Note 55] Canada is funding 43 projects,[Note 56] focusing on science and research activities related to climate change impacts and adaptation, and the health and well-being of northern communities.[Note 57]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC took effect in 1994 and includes the participation of 192 countries around the world, including Canada. The UNFCCC is an international treaty that considers options to reduce global warming and adapt to inevitable temperature changes. In support of the treaty, participating countries agreed to develop national programs to slow climate change and support climate change activities in developing countries.

- The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Canada is one of the member countries of the IPCC, which the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization established in 1989 to "provide the governments of the world with a clear scientific view of what is happening to the world's climate."[Note 58] One of the IPCC's working groups focuses on climate change impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. The IPCC is currently working on a special report: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation.

Despite substantial documented evidence of the Government of Canada's commitment to address climate change, some key informants said they had limited understanding of how the Program aligns with government priorities. The only climate change-related activity that they identified the federal government as being involved in was the CAA, although they were not clear on how the Program supported it. It is not clear what factors contributed to this; it may reflect that most Program staff do not have responsibilities directly linked to the CAA; as well, it could be the lack of clarity and collaboration around the theme level objectives of the Program. This issue could be further explored in the summative evaluation.

Alignment with INAC priorities

The evaluation found that the Program closely aligns with INAC's priorities.

INAC has a departmental mandate to assist northern communities in efforts to "improve social well-being and economic prosperity; develop healthier, more sustainable communities; and participate more fully in Canada's political, social and economic development – to the benefit of all Canadians."[Note 59] To this end, the Department delivers programs through six strategic outcomes, three of which the Program contributes to: The North – The people of the North are self-reliant, healthy, skilled and live in prosperous communities; The People – Individual and family well‑being for First Nations and Inuit; and The Land – Sustainable management of First Nations and Inuit lands, resources and environment.[Note 60]

Additionally, the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program builds on the following two former INAC programs:

- The Aboriginal and Northern Climate Change Program (ANCCP). The purpose of the ANCCP (2001 to 2003) was to create awareness of and interest in sustainable energy use and production in northern communities. Through this program, many opportunities were realized for energy use and GHG emissions reductions.

- The Aboriginal and Northern Community Action Program (ANCAP). INAC delivered this $30.7 million program (2003 to 2007) in partnership with NRCan. The aimed to create sustainable energy solutions for northern communities, with a specific focus on reducing the consumption of diesel fuels.

While the ANCCP was an awareness program, the was an action program that assisted northern communities with the development of initiatives related to community energy planning, capacity building, raising awareness, energy efficiency, renewable energy, alternate diesel technologies, and sustainable transportation.[Note 61] Although these programs focused on mitigation, adaptation measures were also an important component. INAC and the northern community at large deemed these programs as highly successful.[Note 62]

5.1.3 No evidence of program duplication

This section responds to the following evaluation question: Does the Program complement or duplicate/overlap with other Adaptation initiatives? If so, what actions should be taken to address unnecessary duplication or overlap?

The evaluation found no evidence of duplication with other programs. None of the funded projects received funding from another climate change adaptation program. Key informant interviews provided two explanations for this:

- No other formal climate change programs aimed at the North exist.

- The Program works with other federal departments involved in climate change adaptation activities, such as NRCan and Environment Canada EC), to ensure their programs do not duplicate each other.

As a result of the Program, projects have leveraged about $1.9 million in financial and in-kind resources from other federal departments, provincial governments, professional associations/consultants, and community organizations. This includes $164,000 of financial resources and $366,000 of in-kind resources in 2008–09, and $330,000 of financial resources and $1 million of in-kind resources in 2009–10.

Complementary activities

Although the Program does not duplicate or overlap with other programs, the evaluation found some evidence that complementary activities are occurring. The literature indicates that the territorial governments are beginning to develop territory-wide climate change action plans.

- Yukon Government Climate Change Action Plan. In February 2009, the Yukon government released a Climate Change Action Plan, which builds on the Climate Change Strategy that it released in 2006. Some of the planned actions are being conducted with funding from the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program.

- Nunavut Climate Change Adaptation Plan. During the summer of 2008, the Nunavut Climate Change Adaption Plan (NCCAP) was in development and a draft version of the Plan was expected to be ready for circulation in the fall of 2008.[Note 64] Several of the projects funded through the Assist Northerners in Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and Opportunities Program are intended to support the development of the NCCAP.

- Northwest Territories Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Report. In 2008, Northwest Territories Environment and Natural Resources developed the Northwest Territories Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Report. The report describes the climate change impacts being observed in the Northwest Territories and identifies the adaptation measures being undertaken to respond to those impacts.

The literature also provides examples of northern communities that are adapting to climate change, without assistance from the Program; however, most of these adaptations are reactive responses to immediate threats and involve behavioural changes such as taking extra care and caution while travelling, altering hunting practices, preparing for anticipated flooding. They are not implementing large-scale, expensive adaptation projects without support from other sources.

- The Council of Yukon First Nations. The Council of Yukon First Nations (CYFN), representing 11 of the 14 First Nations in Yukon and four Gwich'in First Nations in the Mackenzie Delta region, is developing climate change adaptation strategies at the community level. Its climate change strategy is built around three themes: 1) core capacity to coordinate and manage Yukon First Nation responses to climate change impacts; 2) support for directed community research; and 3) communication, public education, and partnership development. CYFN's approach to enhancing the adaptive capacity of local communities is to provide the climate change concerns of Yukon First Nations to the right people at the right time. Additionally, Yukon First Nation Elders have established the Elders Panel on Climate Change, which has participated in and helped direct CYFN's work on climate change.[Note 65]

- Arctic Bay and Igloolik, Nunavut. Table 3 identifies the adaptation strategies that are being implemented in Arctic Bay and Igloolik. Similar responses have been documented throughout Nunavut.[Note 66]

| Climate change impact | Adaptation strategy |

|---|---|

| Unpredictability of weather, wind, and ice | Taking extra food, gas, and supplies in anticipation of potential dangers when venturing out on the land |

| Making sure they travel with others when possible | |

| Being risk adverse by avoiding travelling on the land or water if they expect bad weather | |

| Using TV and radio weather forecasts to complement traditional forecasts | |

| Taking along new equipment, such as personal location beacons, immersion suits, and satellite phones when venturing out on the land | |

| Waves or stormy weather (for summer boating) | Waiting in the community for adequate conditions |

| Identifying safe areas where shelter can be found prior to travel | |

| Snow covered thin ice | Avoiding snow covered areas |

| Taking extra care while travelling | |

| Reduced accessibility to hunting areas | Waiting in the community until hunting areas are accessible |

| Switching species and location | |

| Developing new access routes (e.g., overland travel instead of ice travel) | |

| Sharing country food[Note 67] | |

| Source: Ford et al., 2007, pp. 154-155 | |

- Sachs Harbour, Northwest Territories. Sachs Harbour is using several adaptive measures to address climatic and environmental changes:

- Hunters are staying closer to the community while out on the ice to avoid increasingly unpredictable sea-ice conditions;

- Weather and environmental conditions are being closely monitored due to increased unpredictability;

- All-terrain vehicles instead of snowmobiles are used for travel when there is inadequate snow cover; and

- New lakes are being used for fishing when erosion has made it difficult to fish or when fish stocks have been depleted.[Note 68]

- Hunters are staying closer to the community while out on the ice to avoid increasingly unpredictable sea-ice conditions;

- Aklavik and Fort Liard, Northwest Territories. Aklavik and Fort Liard have implemented adaptation strategies to address flooding. They include:

- Developing strong awareness of signs and conditions preceding a flood event;

- Moving belongings in preparation for anticipated flooding;

- Broadcasting flooding-related information within the community; and

- Developing evacuation procedures.[Note 69]

- Developing strong awareness of signs and conditions preceding a flood event;

Although a small number of key informants acknowledged that some communities are reactively adapting to climate change out of necessity, they indicated that communities require additional resources to formulate proactive responses. These resources would help bring communities together to share best practices and lessons learned and facilitate the development of collaborative networks across communities.

5.2 Design and delivery

This section provides the findings related to the design and delivery of the Program. It discusses the Program objectives, implementation, management and accountability, performance measurement, and best practices/lessons learned.

5.2.1 Program objectives

This section responds to the following evaluation question: Has the Program been implemented (or is it on track to being implemented) as planned?

The evaluation found that all of the funded projects support the Program's objectives to assess and identify risks and opportunities related to the impacts of climate change and to develop climate change adaptation plans. The Program is funding projects that are designed to raise awareness of climate change, identify climate change risks and opportunities, generate new scientific knowledge, help build capacity to adapt to climate change, and begin work on developing adaptation plans (see Section 5.3 for information on preliminary results). Projects closely relate to the Program objectives and rationale for the Program because, through the proposal review process, program staff work extensively with proponents to ensure proposals meet Program and departmental requirements and the specific needs of communities.

However, the second objective of the Program (see Section 3.1) requires clarification. This objective suggests the Program is intended to assist northerners to develop and implement climate change adaptation projects and/or plans. Much of the Program focuses on the development of adaptation planning. Most costs related to implementation (e.g., infrastructure and capital costs) are not eligible for funding as the Program does not have access to the financial resources needed to support implementation projects.

5.2.2 Program was implemented as planned

This section responds to the following evaluation question: Has the Program been implemented (or is it on track to being implemented) as planned?