Archived - Formative Evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education Program

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 24, 2010

(Project Number: 1570-7/09056)

PDF Version (273 Kb, 39 Pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Methodology

- 3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

- 5. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Evaluation Matrix

- Appendix B - Interview Guides

List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

The formative evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education (PSE) Program (conducted in 2009‑10) will be followed by a summative evaluation of Elementary/Secondary Education in 2010-11, in accordance with the agreement reached between Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Treasury Board Secretariat in May 2008. The formative evaluation study is required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program, which expire March 31, 2010. The summative evaluation will begin in 2010-11 and be completed in 2011-12, in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13.

While the summative evaluation scheduled for 2010-11 is intended to entail a systematic review of educational outcomes with extensive consultation of First Nations and Inuit education representatives, this evaluation does address relevance and, to the extent possible, performance. Further, this study provides a preliminary examination of the state of information on education in INAC; reviews existing literature on First Nations education; and provides some additional insight on assessing educational outcomes in order to lay the groundwork for the summative evaluation.

The overall objective of INAC's post-secondary education programming is to improve the employability of First Nation, Inuit and Innu individuals by providing eligible students with access to education and skill development opportunities at the post-secondary level. This is expected to lead to greater participation of these individuals in post-secondary studies, higher graduation rates from post-secondary programs and higher employment rates. It is expected that students funded by this program will have post-secondary educational outcomes comparable to other Canadians.

INAC's post-secondary education programming is primarily funded through two authorities: Grants to Indians and Inuit to support their post-secondary educational advancement, and Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education – Contributions to support the post-secondary educational advancement of registered Indian and Inuit students.

The evaluation examined PSE program activities, including all three components of the post-secondary education programming, namely, the Post-Secondary Student Support Program, the University and College Entrance Preparation, and Indian Studies Support Program.

In line with Treasury Board requirements, the evaluation looked at issues of relevance (i.e. continued need, alignment with government priorities, alignment with federal roles and responsibilities), performance (demonstration of efficiency and economy), and design and delivery.

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following multiple lines of evidence (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix[Note 1]):

- Literature Review:

A literature review was conducted using national and international sources. This included, but was not limited to, Aboriginal-specific literature, academic journals, newspaper articles, reports from relevant national and international organisations, and federal/provincial/territorial government websites. - Document and File Review:

A document and file review was undertaken and included Treasury Board Submissions, previous audits and evaluations, previous Results-based Management and Accountability Frameworks, management plans, progress and performance reports, project files, and other administrative data. - Data Analysis:

A review of the National Post-Secondary Education System (NPSES) database was undertaken for fiscal years 2004-05 to 2008-09. However, as data were still being aggregated and analysed by the program at the time of writing the report, NPSES data will not be included in the formative evaluation.

An analysis of Canadian Census data was further undertaken, as well as a statistical analysis of data from the Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, which is a composite index of census data measuring well-being in the areas of income, education, housing, and labour force activity.

An analysis of the First Nation and Inuit Transfer Payment system was also undertaken to determine budgeted and actual expenditures by region. - Key Informant Interviews:

A total of 28 interviewees (both INAC staff and key stakeholders) were interviewed to address formative questions (three INAC Headquarters, 23 INAC Region, two First Nations). Key informants were selected based on their level of knowledge of education policies and programming, and/or their expertise in First Nations education issues.

Conclusions:

The gap between Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginal people in post-secondary education remains wide and numerous factors, including a rapidly growing Aboriginal population and the increasing cost of tuition and cost of living indicate that the need for support from the federal government to address barriers to accessing post-secondary education will continue to grow. While evidence suggests that needs will continue to increase, the current reporting mechanisms at INAC do not allow for proper measurement of need or outcomes.

Aboriginal access to PSE remains a major federal priority. Improved educational attainment is viewed as key to future Aboriginal participation in the labour market and economic success. The federal government has shared this view on numerous occasions, including Budget 2008 and INAC's Report on Plans and Priorities. INAC is also in the development stages of a new integrated reporting system that will merge many of its stand-alone databases and, it is hoped, increase INAC's ability to report on outcomes while reducing the reporting burden on First Nation and Inuit organisations. However, there is evidence to suggest that INAC has not formalized its roles and responsibilities with regards to PSE since it began providing bands with funding for the program, which has resulted in inequity of services to students and ensured INAC's inability to measure meaningful outcomes at regional and national levels.

Though INAC's main PSE database, the NPSES, was not able to be analysed and reported on for this report, census and CWB Index data show that while there have been marked improvements in education scores in other Canadian communities, very little improvement was seen in First Nation and Inuit communities. Similar to the rest of Canada, Aboriginal women tend to be slightly more successful than their male counterparts in graduating from post-secondary institutions. Interestingly, there is also evidence to suggest that while slightly more Aboriginal people enrol in university, there is a higher graduation rate for Aboriginal people attending college.

Unintended impacts of the PSE program include students feeling increased confidence, as well as students becoming positive role models in their communities. A further unintended impact has been referred to as a brain drain in First Nations communities; in other words, students who leave to be educated in more urban centres have a tendency not to move back to their community.

In terms of possibilities for economy, there is some evidence to suggest that opportunities to leverage money within the current system have not been maximised, and that it can be very difficult for some individual First Nations to seek out these opportunities. Examples of instances where economies of scale have been achieved will most likely become available in the summative evaluation.

The allocation of funding is a clear area of concern for the PSE program.Evidence indicates that the current approach to funding results in allocations is insufficient to meet the demands and is not reflective of actual costs. There is further concern that INAC's funding approach and the lack of guidance to Aboriginal communities on managing the distribution of resources ultimately lead to inequitable access for Aboriginal students to funding.

The quantity of reporting requirements remains an issue, particularly for smaller communities who often do not have the capacity (human or financial) to dedicate to reporting. The Department equally has limited capacity to aggregate and analyse the data it collects. Thus, reports completed by First Nation and Inuit communities often lack in terms of providing quality data to INAC, and INAC subsequently cannot maximise its use of the data to report on results.

It is recommended that INAC:

- With meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, explores alternatives to its PSE funding approach to maximise economies of scale and retains the principles of First Nation Control of First Nation Education;

- Ensures that it is comprehensively analysing the information collected in the NPSES tool to track student results in order to maximise its ability to meaningfully report on outcomes;

- Ensures its new approach to collecting data allows for the ability to link and systematically mine data on expenditures and outcomes; and

- With meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, clarifies roles and responsibilities of the Department, keeping in mind its responsibility to report results to Canadians.

Management Response / Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title/Sector) | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. That INAC, with meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, explores alternatives to its post-secondary education funding approach to maximise economies of scale and retains the principles of First Nations Control of Education. | INAC, with input from First Nation education experts and other stakeholders, will review and undertake analysis of existing research on financial and non-financial barriers to access to post-secondary education. | Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Directors General, Regional Operations. | Fall 2010 |

| 2. That INAC ensures that it is comprehensively analysing the information collected in the National Post-Secondary Education System tool to track student outcomes including graduation, drop-out, length of time to completion and entry into the labour force, all by academic program in order to maximise its ability to meaningfully report on outcomes. | INAC will review the data captured in the First Nations Post Secondary Education System to determine the relevant and pertinent data needed to support improved reporting on outcomes. The Education Information System, presently under construction, will improve the ability to report to Canadians and First Nations. |

Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Directors General, Regional Operations, CIO | Education Information System launch planned for September 2012. |

| 3. That INAC ensures its new approach to collecting data allows for the ability to link and systematically mine data on expenditures and outcomes. | The Education Information System, presently under construction, will provide the ability to collect, link, and report on the financial and non-financial data, and will support mining the data to accurately report on expenditures and outcomes. | Director General, Education Branch, ESDPP, with support from Regional Directors General, Regional Operations. | 2012-13 Completion is contingent on EIS implementation |

| 4. That INAC, with meaningful input from First Nations education representatives, clarifies roles and responsibilities of the Department, keeping in mind its responsibility to report results to Canadians. | Post-secondary education is a matter of shared responsibility. The Government of Canada supports access to post-secondary education as a matter of social and economic policy. | N/A | N/A |

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The formative evaluation of the Post-Secondary Education (PSE) Program (conducted in 2009-10) will be followed by a summative evaluation of Post-Secondary Education in 2010-11, in accordance with the agreement reached between Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and Treasury Board Secretariat in May 2008. The formative evaluation study is required to approve the continuation of terms and conditions of the program, which expire March 31, 2010. The summative evaluation will begin in 2010-11 and be completed in 2011-12, in time for consideration of policy authority renewal in 2012-13.

While the summative evaluation scheduled for 2010-11 is intended to entail a systematic review of educational outcomes with extensive consultation of First Nations and Inuit education representatives, this evaluation addresses relevance and, to the extent possible, performance. Further, this study provides a preliminary examination of the state of information on First Nations education in INAC; reviews existing literature on First Nations education; and provides some additional insight on assessing educational outcomes in order to lay the groundwork for the summative evaluation.

1.2 Program Profile

1.2.1 Background and Description

Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the Parliament of Canada legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians." Canada exercised this authority by enacting the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, the enabling legislation for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND). The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary education services to Indian children living on reserves. Thus, the Indian Act (1985) provides the Department with a legislative mandate to support elementary and secondary education for Registered Indians living on reserve.

Since the early 1960s, DIAND has sought incremental policy authorities to undertake a range of activities to support the improvement in the socio-economic conditions and overall quality of life of Registered Indians living on reserve. These activities include support of Indian and Inuit access to and participation in PSE programs and support for cultural education for Indians and Inuit. Thus, DIAND's position on its involvement in post-secondary education is that it is a matter of policy.

Although there have been significant gains since the early 1970s, First Nation participation and success in post-secondary education still lags behind that of other Canadians. Drop-out rates are higher for First Nations than other Canadian students. Increasing Indian and Inuit retention rates and successes at the post-secondary programming level, as well as facilitating Indian and Inuit participation in, and achievement of, post-secondary education will support the strategic goal of greater self-sufficiency, improved life chances, and increased labour force participation.

INAC's post-secondary programming is primarily funded through two authorities: Grants to Indians and Inuit to support their post-secondary educational advancement, and Payments to support Indians, Inuit and Innu for the purpose of supplying public services in education – Contributions to support the post-secondary educational advancement of registered Indian and Inuit students.

This evaluation will look at all three components of the PSE programming, namely, the Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP), the University and College Entrance Preparation (UCEP), and Indian Studies Support Program (ISSP).

PSSSP is the primary component of the PSE program. PSSSP provides financial support to First Nation and Inuit students who are enrolled in post-secondary programs including: community college and CEGEP diploma or certificate programs; undergraduate programs; and advanced or professional degree programs.

UCEP provides financial support to First Nation and Inuit students who are enrolled in UCEP programs to enable them to attain the academic level required for entrance to degree and diploma credit programs.

ISSP program provides Indian organisations, Indian post-secondary institutions and other eligible Canadian post-secondary institutions with financial support for the research, development and delivery of college and university level courses for First Nation and Inuit students.

1.2.2 Program Objectives and Expected Outcomes

According to the program's Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF), the overall objective of INAC's PSE programming is to improve the employability of First Nation, Inuit and Innu by providing eligible students with access to education and skill development opportunities at the post-secondary level. This is expected to lead to greater participation of these individuals in post-secondary studies, higher graduation rates from post‑secondary programs and higher employment rates. It is expected that students funded by this program will have post-secondary educational outcomes comparable to other Canadians.

Education falls under INAC's strategic outcome, "The People," whose ultimate outcome is "individual and family well-being for First Nations and Inuit." Education is its own Program Activity, which includes the following sub-activity covered in this evaluation: Post‑Secondary Education.

1.2.3 Program Management, Key Stakeholders and Beneficiaries

The management of education programming at INAC is undertaken by the Education Branch in the Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships Sector (ESDPP).

INAC arranges for the administration of the funding for PSSSP services with the chiefs and councils of First Nations. When chiefs and councils choose to continue having INAC deliver services on reserve or administer some components of the PSSSP program funding, INAC may make grant payments directly to individual Registered Indian (First Nation or Innu) and Inuit participants. The Department may also grant payments directly to individual First Nation students who are not members of a band (registered in the General Register) and to individual Inuit students who are normally resident outside Nunavut or the Northwest Territories.

Eligible recipients of funding are Registered Indians and Inuit students who ordinarily reside in Canada, have been accepted by an eligible post-secondary institution into either a degree or certificate program, or a university or college entrance preparation program, and enrol with and maintain continued satisfactory academic standing within that institution. Applicants for UCEP must not have previously received financial support from INAC's PSE program, although an exemption may be given for medical reasons.

1.2.4 Program Resources

In 2008-09, INAC's PSE programming received $344 million in funding. An extraction was taken from the First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payment (FNITP) System for 2003-04 to 2004-05, and 2007-08 to 2008-09. Note that 2006-07 was excluded from this analysis due to data concerns that were not resolved in time for the release of this report, but will be included in the summative evaluation scheduled for 2010-11, which will also include updated expenditure data for 2009-10.

Education programming is funded through annual Comprehensive Funding Arrangements (CFA) and five-year DIAND/First Nations Funding Agreements (DFNFA). These arrangements include various funding authorities, notably, grants, contributions, Flexible Transfer Payments (FTP) and multi-year block funding under Alternative Funding Arrangements (AFA).

The allocation of program funding involves the distribution of funds from Headquarters (HQ) to the regions and from the regions to the recipients. The DFNFAs are formula-driven, and are consistent throughout the country. The CFA allocation model for the program, on the other hand, varies sometimes significantly by region. The 2009 Audit of PSE programming found that this variance may be causing inequitable access to program funding.

In terms of the allocation of funds from HQ to the regions, program funding is a component of each region's annual core budget. The Education Branch does not determine the amount of program funding to be allocated to each region. This is the responsibility of the Resource Management Directorate in Finance at HQ. National budget increases (currently two percent annually) are allocated to each region in proportion to their existing budgets. The regions have the authority to allocate funds across the various programs included in their core budget and therefore, ultimately decide the extent of program funding to provide to their recipients.

2. Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation examined PSE program activities, including all three components of the PSE programming, namely, PSSSP, UCEP, and ISSP. This evaluation will provide information on relevance and, to the extent possible, performance to support the management of program authorities in compliance with the Policy on Transfer Payments. In addition, this evaluation will provide some preliminary information on the state of data collection in post-secondary programming and assist in contextualizing and framing the questions for the summative evaluation in 2010-11. Terms of Reference were approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on June 4, 2009. A contract with TNS Canadian Facts for two technical reports based on a document/file review and key informant interviews was approved in October 2009, and a contract with Harvey McCue Consulting for a technical report based on a literature review was approved in January 2010. Data collection and analysis was undertaken primarily between January and February 2010.

2.2 Evaluation Issues and Questions

In line with the Terms of Reference, the evaluation focused on the following issues:

Relevance

- Continued Need

- To what extent are the intended outcomes of the program in line with the needs of First Nations students? Is the post-secondary program capable of meeting these needs?

- To what extent are the intended outcomes of the program in line with the needs of First Nations students? Is the post-secondary program capable of meeting these needs?

- Alignment with Government Priorities

- To what extent are the objectives of the Post-Secondary Education Program aligned with the Government of Canada's approach to First Nations education?

- To what extent are the objectives of the Post-Secondary Education Program aligned with the Government of Canada's approach to First Nations education?

- Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- Is this program still a priority of INAC and/or the federal government?

Effectiveness

- Success (or Performance)

- To what extent is the post-secondary program achieving the intended outcomes?

- How are existing partnerships (e.g. with other government departments, provinces and the private sector) benefitting or impacting students, and education and skills development, more broadly?

- Have there been any unintended positive or negative impacts of the program?

- To what extent is the post-secondary program achieving the intended outcomes?

- Demonstrations of Efficiency and Economy

- Can the same amount of resources be used to produce better outcomes?

- Do the administrative systems and operational practices allow for the efficient delivery of the post-secondary program in a cost-effective manner?

- Can the same amount of resources be used to produce better outcomes?

Design and Delivery

- Design

- Does the program have clearly stated activities, outputs and outcomes? How and to what extent can these be measured?

- What is the program's reach and target? Is this clearly articulated in the program authorities?

- Are the roles and responsibilities of all parties well defined (i.e. INAC, regional management organisations (RMO)?

- Does the program have clearly stated activities, outputs and outcomes? How and to what extent can these be measured?

- Delivery

- Are the current funding instruments the most effective and efficient methods to manage the program?

- Are there any capacity issues for INAC, RMO's, and/or tribal/band councils regarding the administration and delivery of the program?

- Do other key challenges exist with respect to the administration and delivery of the program (for schools, RMOs, tribal/band councils, INAC regional offices, INACHQ, etc)? If so, what are these challenges?

- Are the current funding instruments the most effective and efficient methods to manage the program?

Other evaluation issue(s)

- What recommendations, options, alternatives, possible strategies or changes should be considered to achieve the intended outcomes?

2.3 Evaluation Method

The following section describes the data collection methods used to perform the evaluation work, as well as the major considerations, strengths and limitations of the report.

2.3.1 Data Sources

The evaluation's findings and conclusions are based on the analysis and triangulation of the following multiple lines of evidence (see also Appendix A, Evaluation Matrix[Note 2]):

- Literature Review:

A literature review was conducted using national and international sources. This included, but was not limited to, Aboriginal-specific literature, academic journals, newspaper articles, reports from relevant national and international organisations, and federal/provincial/territorial (F/P/T) government websites. - Document and file review:

A document and file review was undertaken and included Treasury Board (TB) Submissions, previous audits and evaluations, previous RMAF/Risk-based Audit Framework's, Office of the Auditor General reports, management plans, progress and performance reports, project files, and other administrative data. - Data Analysis:

A review of the National Post-Secondary Education System (NPSES) database was undertaken for fiscal years 2004-05 to 2008-09. However, as data were still being aggregated and analysed by the program at the time of writing the report, NPSES data will not be included in the formative evaluation.

An analysis of Canadian census data was further undertaken, as well as a statistical analysis of data from the Community Well-Being (CWB) Index, which is a composite index of census data measuring well-being in the areas of income, education, housing, and labour force activity.

An analysis of the FNITP system was also undertaken to determine budgeted and actual expenditures by region. - Key informant interviews:

A total of 28 interviewees (both INAC staff and key stakeholders) were interviewed to address formative questions (three INACHQ, 23 INAC region, two First Nations). Key informants were selected based on their level of knowledge of education policies and programming, and/or their expertise in First Nations education issues.

2.3.2 Considerations and Limitations

The formative evaluation of PSE is largely administrative, and focuses mainly on how INAC collects and uses data to determine the needs and outcomes of students. This is reflected in the number of interviewees, as well as the limited involvement of individuals and organisations outside INAC, including First Nations representatives. As the summative evaluation to be administered in 2010-11 will focus heavily on results, including achieved outcomes for students and First Nations communities, extensive involvement of First Nations and Inuit organisations and other experts will be sought both in the design of the summative study and for inclusion as key informants.

Significant delays in getting the proper mechanisms in place to move the evaluation forward caused considerably tight timelines and impacted the extent to which information could be collected and examined. As a consequence, the response rate of First Nations representatives contacted for key informant interviews was extremely low for this study. Additionally, a full census of reports available through INAC's data systems was not obtainable; and a sample of reports was pulled to examine the state of information flow and reporting. These constraints also hampered the resolve of data integrity issues with respect to examining program expenditures.

While it was originally anticipated that data would be analysed using NPSES reports on UCEP and PSSSP, there were significant data integrity concerns, including irregularities in data reports, and concerns regarding data reliability. At the time of writing this formative evaluation study, revised reports from NPSES were being generated by the program that will be included in the summative evaluation. Given that NPSES is the most thorough element of data collection for PSE at the federal level and includes data on graduation, drop-out, and is gender-specific, it contains very important information on moving forward. It is, thus, critical to ensure these data are fully assessed for reliability and are accurately analysed before drawing conclusions from the information contained within the database.

In examining information on program expenditures, there are concerns with the accuracy and completeness of data contained in this particular extraction, given that the data were extracted using current coding mechanisms and expenditures not coded under these would be missed (i.e. any codes used in previous fiscal years).

Of key concern in using data from the Canadian Census and the CWB Index, is that data are only reflective of individuals measured at the time of the census. Additionally, there are numerous First Nation communities that do not participate in the Canadian Census. Thus, neither the Canadian Census nor the associated CWB data are able to account for individuals who complete or leave school and then leave the community and move to a non-First Nations community, or who leave for post-secondary training and do not return to the community. The CWB Index also only includes communities with a population of greater than 65 people. It is also critical to note that the census indicator, and thus, the formula to calculate CWB score for education, changed for the 2006 Census. Whereas, the census prior to 2006 included data on functional literacy (those aged 15 or older with at least a grade 9 education) and those aged 20 or older with at least a high school education, the 2006 Census included data on this latter variable, but not on functional literacy, and instead on those aged 25 or older with at least a bachelor's degree. This is a critical consideration because the formula for CWB had to change accordingly and thus, the score prior to 2006 and the score for 2006 do not measure the same indicator. Analysis of CWB data between 1981 and 2006 shows a modest but steady increase in CWB score for First Nations communities up to 2001, and from 2001 to 2006, there is either a decline or levelling off of CWB Education score. Given there is no theoretical explanation for this sudden change, it is highly probable that this is related to the change in methodology. Thus, data between 2006 and the other census years are not directly comparable.

Finally, given that there is a high tendency of youth to move off reserve and that First Nation populations are highly mobile,[Note 3] results from both the Canadian Census and the CWB Index must be interpreted cautiously.

Key informants for this study were selected based on the recommendations of the Advisory Committee with respect to persons who would be most knowledgeable about INAC education programs and policies, and First Nations education issues. Thus, the selection is inherently biased as no formal selection procedure was used. This issue will be mitigated in the summative evaluation with a formal selection procedure for key informants from First Nations.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of INAC's Audit and Evaluation Sector was the project authority for the PSE evaluation, and managed the evaluation in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy and Quality Control Process.

An Advisory Committee was established between INAC's EPMRB, ESDPP and the Assembly of First Nations, which considered both the Elementary/Secondary and Post-Secondary Education evaluations. The purpose of the Advisory Committee was to work collaboratively to produce evaluation products, which are reliable, useful and defendable to both internal and external stakeholders.

Furthermore, the evaluation team organised an internal peer review of the methodology report and held two validation sessions regarding technical reports.

A significant portion of the work for this evaluation was completed in-house. Two contractors, TNS Canadian Facts and Harvey McCue Consulting, were utilised for some portions of the work. Oversight of daily activities was the responsibility of the EPMRB evaluation team, headed by a Senior Evaluation Manager. The EPMRB evaluation team identified key documents, provided documentation, data for the study, and names and contact information of First Nations representatives, and INAC resource persons at HQ and regional offices. The team further expeditiously reviewed, commented on and approved the products delivered by the contractors.

3. Evaluation Findings - Relevance

The evaluation looked for evidence that the intended outcomes of PSE programming at INAC are in line with the needs of First Nations students. It further looked at whether PSE programming is consistent with government-wide and departmental priorities, and roles and responsibilities.

There is a clear demonstration of need for Aboriginal PSE programming given the significant gap in enrolment and graduation rates that exist between Aboriginal populations (particularly First Nations on reserve) and non-Aboriginal populations, and the implications this may have on access to labour market participation.

Post-secondary programming is aligned with federal government priorities and roles and responsibilities for promoting the elimination of systemic barriers faced by Aboriginal Canadians and, specifically, First Nations education. This is also reflected in the stated priorities to facilitate First Nations students in completing education and consequently, be better positioned to achieve labour market and economic success.

3.1 Continued Need

Population growth trends and the key informants interviewed in this study suggest that the growth of Aboriginal populations will undoubtedly generate further need with respect to education. As stated in INAC's 2009-10 Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP),[Note 4] Canada's Aboriginal population is young and growing almost twice as fast as the country's general population (1.8% per year vs. 1.0%).

According to Census 2006, only six percent of Aboriginal people have received a university degree, compared to the rest of the Canadian population at 18 percent.

Generally, key informants indicated that the current level of need for post-secondary access outweighs the capacity through funding. While post-secondary enrolment rates among Aboriginal populations have remained relatively stable in recent years, key informants indicated that this is not a result of lack of interest but rather a limited budget, as well as increased tuition and cost of living. For example, Canadian full-time students in undergraduate programs are faced with persistently rising tuition costs. On average, students paid $4,917 in tuition fees in 2009/2010, compared with $4,747 in 2008/2009.[Note 5] College fees, while lower than university tuition, have been increasing, as well as related expenses for books, accommodation and living costs.[Note 6] At best, a fixed funding cost may at best keep enrolment rates stable if there is not enough funding to provide each interested and eligible person the opportunity to take post‑secondary training. According to areport released by INAC's Information Management Branch in 2009, the number of actual students funded for post-secondary education has decreased 12 percent between 1997-98 and 2007-08.[Note 7] Unfortunately, data on the frequency of individuals not able to attend post-secondary studies due to insufficient funding is not tracked at the federal level, and would only be available from First Nations. A more thorough review of this issue will be examined in the summative evaluation, which will include extensive consultation with First Nations and Inuit education organisations and a significant amount of First Nations and Inuit interviewees.

While there are data gaps in specific student performance with respect to enrolment, retention and completion of post-secondary studies, an analysis of CWB Index data suggests that, with the exception of Quebec, in the vast majority of cases, CWB Education[Note 8] scores decreased the further away people lived from a service centre (according to Geo-zone categories). [Note 9] For some regions, particularly Atlantic and British Columbia, this has become more pronounced over time. In most cases, the reason for this trend is the much higher CWB Education scores in Zone 1 communities compared to Zones 2, 3 and 4. This is most apparent in Northwest Territories and in Quebec, where the CWB Education score does not necessarily decrease with increasing distance across all geo-zones, but scores for Zone 1 communities are clearly higher than the rest, which are not very different from one another.

Further, when analysing CWB Education scores in relation to Environmental Remoteness,[Note 10] the tendency towards poorer education scores with increasing distance to the North was less evident, though still present. This tendency, however, eems to be becoming more pronounced over time, particularly in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia Additionally, there was a tendency for communities classified as Environmental Remoteness B to have higher CWB Education scores than all others (there were no Class A communities in the data). This data suggests that there is a clear need to address specific community circumstances through education programming. Analysis of CWB data is further discussed in Section 4.1 on impacts.

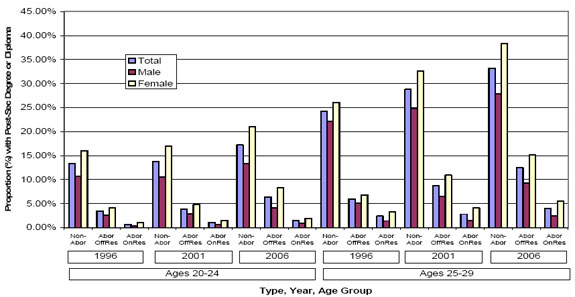

Differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations are also illustrated by Canadian Census data. As shown in Figure 1 below, the proportion of non-Aboriginal populations aged 20-29 with a post-secondary degree or diploma[Note 11] hasbeen consistently much higher than Aboriginal populations either off or on reserve, and has shown sharp increases over the three census years, particularly for populations in their late 20s. Aboriginal populations off reserve have shown modest but noticeable increases over time; however, populations on reserve, which have consistently had far lower proportions of individuals with post-secondary education, have not improved over time. These results, however, must be interpreted with caution, as it is entirely possible that Aboriginal individuals with post-secondary training may simply not return to, or move to, First Nation communities on reserve due to fewer employment opportunities than in larger centres. See Section 4.1 for a more detailed discussion.

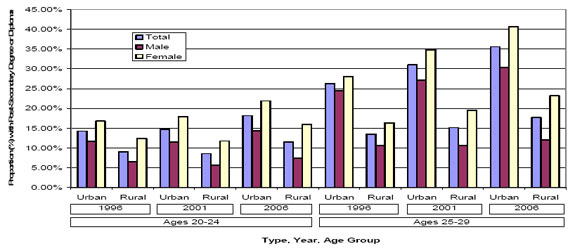

Figure 1: Proportion (%) of Age Groups with a Post-Secondary Degree or Diploma by Gender by Type (non-Aboriginal; Aboriginal Off Reserve;

Aboriginal On Reserve),[Note 12] by Year, by Age Group of

Interest[Note 13] (20-24; 25-29)

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of Canadian Census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by type, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a status (non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal Off-reserve and Aboriginal On-Reserve) by gender, year (1996, 2001 and 2006), and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 13% of the Non-Aboriginal population (11% of males and 16% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 3.5% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (3% males and 4% of females) and 1% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.5% of males and 1.5% of females).

In 2001, approximately 14% of the Non-Aboriginal population (11% of males and 17% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 4% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (3% males and 5% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

In 2006, approximately 18% of the Non-Aboriginal population (14% of males and 22% of females) aged 20-24 post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (4.5% males and 8% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 24.5% of the Non-Aboriginal population (22% of males and 27% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 6% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (5% males and 7% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2% of males and 4% of females).

In 2001, approximately 29% of the Non-Aboriginal population (25% of males and 33% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 9% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (7% males and 11% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2% of males and 4% of females).

In 2006, approximately 33% of the Non-Aboriginal population (28% of males and 38% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 13% of the Aboriginal Off-Reserve population (9.5% males and 15.5% of females) and 4% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2.5% of males and 5.5% of females).

It is not clear whether the statistics for on reserve populations are reflective of an issue with individuals completing high school and advancing to post-secondary, or whether they are a result of students leaving the reserve to pursue post-secondary education. However, according to a study performed by INAC in 2004,[Note 14] as well as key informant interviews, Aboriginal students from Northern communities or reserve schools are often lagging academically behind their provincial counterparts by one to two years. This makes university preparation and counselling essential components to ensuring First Nations success in post-secondary education.

3.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

In the Government of Canada's annual report to Parliament Canada's Performance – The Government of Canada's Contribution 2008-09, First Nations education falls under the outcome area "A Diverse Society That Promotes Linguistic Duality and Social Inclusion." According to the report, government efforts in this outcome area are intended to promote, among others, the elimination of systemic barriers faced by Aboriginal Canadians and, specifically, First Nations education.

The need to improve Aboriginal education outcomes was also identified in Budget 2008. In this report, the government committed to continuing its review of First Nations and Inuit PSE programs to ensure their coordination with other programs, and that they provide the support to facilitate First Nations and Inuit students' completing their education.

Alignment of Aboriginal education with government priorities is also discussed in the 2009-10 RPP, with the priority in First Nations education being to build a foundation for structural reform to improve education outcomes. The Government's strategy for building this foundation is in line with what was outlined in Budget 2008; namely, to work with First Nations communities to help schools develop success plans, conduct learning assessments, develop performance measurement systems, and develop tripartite partnerships with First Nations communities and provinces.

A review of the Government of Canada priorities suggests that improved First Nations educational attainment is key to future participation in the labour market and economic success. According to the 2008-09 RPP, the benefits of this will be felt in First Nations communities and Canada at large through higher levels of self-esteem, well-being and participation in Canadian society. What is more, in 2009, the Centre for the Study of Living Standards indicated that if the educational attainment gap between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals were to close by 2017, an additional $71 million could be infused into the Canadian economy.

Additionally, INAC, in partnership with the Inuit of Canada, as represented by the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and other Inuit and public government bodies, signed the Inuit Education Accord in April 2009. The purpose of the accord is to establish a National Committee on Inuit Education that will work together to develop a strategy for moving forward on educational outcomes for Inuit students. With this initiative, the federal government has made a commitment to promoting social and economic development in the North.[Note 15]

3.3 Alignment with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The federal government obtained its legislative authority in matters pertaining to "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians" under Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The Indian Act (1985), sections 114 to 122, allows the Minister to enter into agreements for elementary and secondary school services to Indian children living on reserves. Despite the fact that the Constitution Act and the Indian Act fail to make explicit reference to post-secondary education, INAC has taken the official view that their involvement in Aboriginal post-secondary education is a matter of social policy rather than a legal responsibility.

INAC pays for education by funding band councils or other First Nations education authorities through several types of funding arrangements, namely, FTP, AFA, DFNFA and CFA.

After the National Indian Brotherhood[Note 16] publication of Indian Control of Indian Education was released in 1972, the federal government accepted the principles of this policy and, in 1974, began funding individual bands to administer PSE funding to their students. Since then, there has been uncertainty around the role of the federal government in First Nations education. In a 2000 report, the Auditor General reported that many INAC regional offices saw their role in First Nations education as funders.[Note 17]

In response to the OAG report, the Standing Committee on Public Accounts expressed its concern regarding the lack of clear roles and responsibilities, stating that "the Department must clarify and formalise its role and responsibilities, otherwise, its accountability for results is weakened and assurances that education funding is being spent in an appropriate fashion are unclear at best."[Note 18]

In the 2004 follow-up[Note 19] to her 2000 report, the OAG expressed concern for "the Department's lack of progress in defining its roles and responsibilities." The OAG goes on to express that "until the Department clarifies these and its capacity to fulfill them, and reaches a consensus with other parties on their own roles and responsibilities, it will remain difficult to make progress in First Nations education and close the education gap."

Partly in response to the OAG's 2000 report, the Department established the Education Branch in 2004. In the branch's 2008 RMAF, it described its role as "being limited to providing funding to support the educational needs of those living on reserve." While some key informants argued that this makes sense in terms of maximising First Nations control of education, others argued that a lack of clarity around education policy from INAC allows for inequity of services to students (both between bands and between bands and the province), and ensures INAC's inability to measure meaningful outcomes at regional and national levels.

INAC's vision is a future in which First Nations, Inuit, Métis and Northern communities are healthy, safe, self-sufficient and prosperous - a Canada where people make their own decisions, manage their own affairs and make strong contributions to the country as a whole.

Education programming is essential to achieving this vision. Numerous publications cite how education is the key to success both in terms of preserving and promoting Aboriginal culture and identity, as well as economic success. A recent report from the Canadian Council on Learning states that learning from—and about—culture, language and tradition is critical to the well-being of Aboriginal people. Indeed, the report finds that such activities play an important role in the daily lives of many Aboriginal learners and are commonplace in Aboriginal communities across Canada.[Note 20] Another report from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards states that an important portion of the employment rate gap can be attributed to lower educational attainment among the Aboriginal population than among the non-Aboriginal population. Aboriginal Canadians are much less likely than non-Aboriginal people to either earn a high school diploma or a post‑secondary certificate.[Note 21]

4. Evaluation Findings - Performance

The evaluation looked for preliminary evidence that students are able to succeed at school, as well as whether INAC's administrative systems and operational practices allow for the efficient and cost-effective delivery of the Post-Secondary Education Program.

While data from the NPSES to be used in the summative evaluation will provide a more complete picture of student results, Canadian Census data suggest there have been small but noticeable improvements among Aboriginal populations in educational attainment overall. However, further analysis of census data and its associated CWB Index suggest that such improvements are very modest or non-existent within First Nations communities on reserve.

4.1 Effectiveness

4.1.1 Achievement of Outcomes

The key tool to report on student outcomes is the NPSES database for UCEP and PSSSP. However, at the time of this report, a revised summary of NPSES data was underway and not available for reporting in the formative evaluation. A full analysis of NPSES data is scheduled for the summative evaluation in 2010-11 (see Section 5.1 for further discussion of NPSES).

An analysis of custom tables from Canadian Census data (see Figure 1) shows a very wide gap between non-Aboriginal populations and Aboriginal populations both on and off reserve in the proportion of the populations having completed post-secondary education for individuals aged 20-29. Despite this gap, the rate of increase in this proportion between non-Aboriginal populations and Aboriginal populations off reserve is roughly similar. That is, increases are being achieved at roughly the same rate (although slightly higher increases for non-Aboriginals). Statistics from Aboriginal populations on reserve, however, do not show such increases; although, it is entirely possible that this is related to a low rate of persons from First Nations communities returning to their community after they complete post-secondary studies. While there are gender differences in that the proportion of post-secondary completion for women is higher than that of men, these differences are consistent with Aboriginal populations off reserve, and of non-Aboriginal populations.

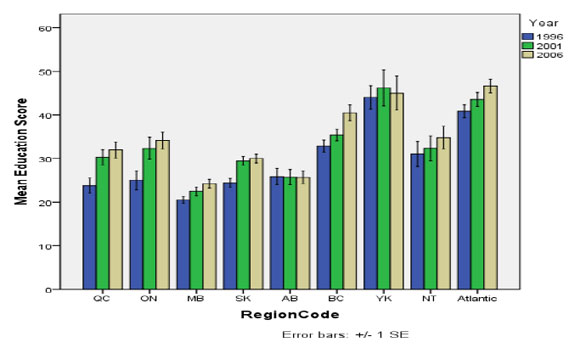

An analysis of CWB Index data further revealed that while there have been increases[Note 22] in CWB Education scores (see Figure 2 below) in most regions (with the exceptions of Alberta, Yukon and Northwest Territories), these increases have been modest compared to the average Canadian community increase (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Mean CWB Education Score for On Reserve Populations

by Region by Census Year

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of CWB Index data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the First Nations mean CWB scores for Education by region and by year. Each region of comparison (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Atlantic) is represented by a cluster of bars with each bar in the cluster representing the year (1996, 2001 and 2006). The mean Education scores recorded for each region, named along the x axis, are indicated along the vertical y axis.

In Quebec, the mean Education score was approximately 24 in 1996, 30 in 2001 and 32 in 2006. The scores for Ontario were 25 in 1996, 32 in 2001 and 34 in 2006. In Manitoba, the scores were 21 in 1996, 23 in 2001 and 25 in 2006. In Saskatchewan, the scores were 25 in 1996, 29 in 2001 and 30 in 2006. In Alberta, the score was approximately 26 for all three years. The scores were 34 in 1996, 36 in 2001 and 42 in 2006 for British Columbia. The scores for Yukon were 44 in 1996, 46 in 2001 and 45 in 2006. In the Northwest Territories, the scores were 33 in 1996, 35 in 2001 and 40 in 2006. The Atlantic region's scores were 41 in 1996, 44 in 2001 and 47 in 2001.

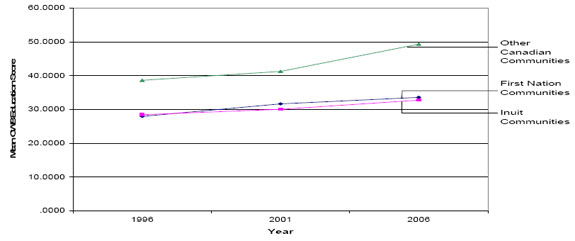

Figure 3: Mean CWB Scores Over Time between First Nation Communities; Inuit Communities and Other Canadian Communities

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of CWB Index data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph indicating the mean Community Well Being (CWB) Education scores for Inuit, First Nations and Other Canadian Communities over the years 1996, 2001 and 2006, each represented by a separate line. The Mean CWB Education Scores are indicated along the y axis and the years are indicated along the x axis.

The graph illustrates that the CWB scores of Inuit were roughly the same as those of First Nations Communities, while remaining markedly lower than the scores of Other Canadian Communities.

According to the graph, the scores for Inuit Communities were approximately in 28 in 1996, 30 in 2001 and 33 in 2006; the scores for First Nations Communities were 27.5 in 1996, 32 in 2001 and 34 in 2006; and the scores for Other Canadian Communities were 38 in 1996, 41 in 2001 and 49 in 2006.

With the exception of Atlantic Canada, there appears to be marked improvements in CWB Education scores for other Canadian communities, but little to no improvement for First Nations and Inuit communities. Generally, the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities is extremely wide and has not narrowed in recent years in any region; in fact, in some instances, the gap appears to be widening.

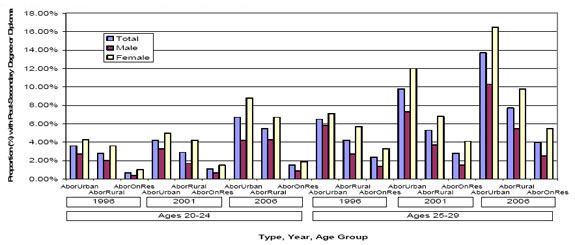

Further analysis of census data reveals that when examining Aboriginal populations off reserve between persons in rural versus urban communities, as shown in Figure 4, that proportions of persons with a post-secondary degree or diploma is greater among urban than rural communities. The data also shows that both the proportions and the rates of improvement for both age groups are considerably higher for Aboriginal populations off reserve in rural communities than for Aboriginal populations on reserve, and this gap is growing considerably over time, especially in examining the 25-29 age group.

Figure 4: Proportion (%) of Age Groups with a Post-Secondary Degree or Diploma by Gender by Type (Aboriginal Urban; Aboriginal Rural; Aboriginal On-reserve), by Year, by Age Group of Interest (20-24; 25-29)

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by status, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a type (Aboriginal Urban, Aboriginal Rural and Aboriginal On-reserve) by gender, total population, year (1996, 2001 and 2006) and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 3.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (3% of males and 4.5% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 3% of the Aboriginal Rural population (2.75% of males and 3.5% of females) and 0.75% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.5% of males and 1% of females).

In 2001, approximately 4.25% of the Aboriginal Urban population (3.25% of males and 5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 3% of the Aboriginal Rural population (1.75% of males and 4% of females) and 1.25% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (0.75% of males and 1.75% of females).

In 2006, approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (4% of males and 9% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 5.75% of the Aboriginal Rural population (4.25% of males and 7% of females) and 1.5% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1% of males and 2% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 6.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (5.75% of males and 7% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 4.25% of the Aboriginal Rural population (2.5% of males and 5.75% of females) and 2.25% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1.5% of males and 3% of females).

In 2001, approximately 9.75% of the Aboriginal Urban population (7.5% of males and 12% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 5.25% of the Aboriginal Rural population (3.5% of males and 7% of females) and 3% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (1.5% of males and 4.25% of females).

In 2006, approximately 13.5% of the Aboriginal Urban population (10.25% of males and 16.5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 7.5% of the Aboriginal Rural population (5.5% of males and 9.75% of females) and 4% of the Aboriginal On-Reserve population (2.5% of males and 5.5% of females).

Also, as shown in Figure 5, while rates for non-Aboriginal populations are consistently higher than those of Aboriginal populations, the gap between urban and rural is roughly similar for both groups and shows a similar trend of widening over time, particularly for populations in their late 20s. These analyses suggest that rural isolation does not independently account for the lower proportions of completion seen among First Nations populations on reserve. It is entirely possible that there are far lower completion rates among populations on reserve, but it is equally plausible that low recruitment or retention of Aboriginal peoples with post-secondary education on reserves may account for this large discrepancy. However, without controlling for degree of isolation and latitude (which is not available for this analysis), other mediating variables associated with being on reserve cannot be ruled out.

Figure 5: Proportion (%) of Non-Aboriginal Population with a Post-Secondary Degree or Diploma by Gender by Type (Urban; Rural), by Year, by Age Group of Interest (20-24; 25 29)

Source: Completed Internally by Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch using an aggregated extract of Census data received from Strategic Planning, Policy and Research Branch

This figure shows a graph comparing the proportion of people with a post-secondary degree or diploma by gender, by status, by year and by age group of interest.

The age groups of interest (20 to 24 and 25 to 29) are segmented along the horizontal x axis. Each cluster of bars on the graph represents a type (Non-Aboriginal Urban and Non-Aboriginal) by gender, by total population, year (1996, 2001 and 2006) and age groups of interest. The proportion of those with a post-secondary degree or diploma is indicated along the vertical y axis.

Within the age group of 20 to 24 years, approximately 14.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (12% of males and 17% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 9% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (7% of males and 12% of females).

In 2001, approximately 14.75% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (11.5% of males and 18% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 9% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (6% of males and 12% of females).

In 2006, approximately 18% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (14% of males and 22% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 11.75% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (7.5% of males and 16% of females).

Within the age group of 25 to 29 years, approximately 26.25% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (24.75% of males and 28% of females) had a post-secondary degree or diploma in 1996, compared to approximately 13.25% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (10.5% males and 16.25% of females).

In 2001, approximately 31% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (27% of males and 35% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 15% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (10% of males and 20% of females).

In 2006, approximately 35.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Urban population (30.5% of males and 40.5% of females) aged 20-24 had a post-secondary degree or diploma, compared to approximately 17.5% of the Non-Aboriginal Rural population (12% of males and 23% of females).

Unfortunately, there are significant limitations to data stemming from the Canadian Census, given that it assesses information from a community at a specific time (i.e. a snapshot), and does not allow for the analysis of entry in or completion of post-secondary education; nor is it able to assess labour force participation, given the high probability of out-migration after completion of secondary school and possible low likelihood of returning to the reserve after completion of post‑secondary education.

In order to fully assess student performance, analysis of the progression from completion of high school, to entry into post-secondary, to completion of post-secondary, and to labour market entry would be essential. As discussed above, while the NPSES for PSSSP and UCEP does not contain this information per se, it does mine data on graduation and drop-out rates by year and gender, and thus, will provide a very useful analysis in the summative evaluation in 2010-11.

In terms of the type of post-secondary studies Aboriginal students tend to pursue, there is evidence to suggest that, with few variations, slightly more Aboriginal students enrol in university than college. There is also evidence to suggest that the reverse is true for graduation rates. In other words, more Aboriginal students consistently graduate from college than university.[Note 23] After a scan of recipient reporting, it appears that the most common areas of study for Aboriginal students include General Arts & Sciences, Education, Business & Commerce and Social Sciences.

Generally speaking, most key informants interviewed stated that the PSE program has had a positive impact on the overall well-being of Aboriginal students. In particular, they indicated that the program provided hope to students, enhanced life skills, a sense of pride and accomplishment, as well as improvements on general outcomes such as health and quality of life that are associated with improved education.

4.1.2 Unintended Impacts

Given the relatively small number of key informants for the formative evaluation and particularly, given the very low number of First Nation participants in the key informant interviews, subjective assessments of unintended impacts were very limited. It is expected that the much broader range of First Nations stakeholders to be interviewed in the summative evaluation will likely have more to say on unintended impacts.

Interviewees in this study did, however, identify a few key positive impacts that were not necessarily within the expressed purpose of post-secondary programming; including increased confidence among students; increased pride in Aboriginal culture; students becoming ambassadors for their communities and positive role models for other First Nations people; and an increased ability among non-Aboriginals to work in Aboriginal communities. To elaborate on the latter point, according to some interviewees there has been a considerable and unexpected uptake of Aboriginal studies programs among non-Aboriginal students. One of the examples provided was a nursing program geared to nurses with aspirations of working with Aboriginal people in the health field. This opportunity allowed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students alike to learn cultural customs and get a sense of First Nations' approaches to health in order to better serve Aboriginal people on or off reserve.

One key unintended outcome that potentially has negative implications is the perceived 'brain drain' from communities. In other words, given the incentives and the likely increased ease of finding gainful employment off reserve, there is anecdotal evidence to suggest there is a loss of skills from communities with respect to individuals who obtain post-secondary education. This is not surprising as in smaller rural communities, opportunities for gainful employment can be somewhat limited. Students who graduate from a post-secondary institution have better chances at making further income if they remain in a more urban setting. This inequity of opportunity means that communities often lack the very people in professions that their students are sent to study. One strategy used to mitigate this has been the use of internet courses through the First Nations SchoolNet program. In some instances, this program has allowed students to earn college and university credits while remaining in their communities.

4.2 Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

4.2.1 Effectiveness of Reporting Procedures

While economic and cost-benefit analyses were not possible for this study due to severe data limitations, common issues of efficiency raised appeared to centre on measuring needs and reporting. Specifically, and as discussed in further detail in Section 5.1, there is a lot of data that is being collected at the local level but is not collected by INAC regional or national levels to be streamlined for consistent reporting. While the reports often describe desired outcomes, they more often list outputs and the actual reporting on outcomes is scant and not streamlined, which makes it difficult to roll-up into a database and analyse. Therefore, a meaningful discussion on efficiency and/or economy is difficult given that outcomes are not clearly or consistently reported, and the little outcome data that is available is not matched to specific activities or expenditures.

Further, the exact method for measuring student needs and outcomes varies from community to community, and results are often kept at the local level. Additionally, an overwhelming majority of key informants indicated that the existing reporting requirements do not provide a good indication of the outcomes achieved though INAC programming. Data on expenditures is also problematic because it is difficult to determine if unused allocations are because of low demand; if poor forecasting is used; or if there are other circumstances such as the timing of allocation receipt that may cause funds to be unused before fiscal year-end reporting.

Overall, the large majority of key informants believe that there is little formal process for ensuring programming reflects the needs and priorities of First Nations. While many cited the fact that programs are community-based and that First Nations have the ability to set local priorities, few could speak to formal consultation processes that ensured cooperation when creating national or regional policies.

4.2.2 Opportunities for Economy

There is evidence to suggest that there are few opportunities to leverage additional resources within the current system, and while many possible external sources exist, First Nations individually are not always able to tap into these resources. The PSE program is often one of many complex programs being managed and reported on by First Nation and Inuit organisations for communities that are relatively small, the majority being less than 1,000 residents. Under this delivery system, these organisations often do not have the human or financial capacity to maximise economies of scale. Despite this, there are Aboriginal education organisations that are dedicated to supporting all Aboriginal learners in improving education outcomes; of particular note are the First Nations Education Steering Committee in British Columbia and the First Nations Education Council in Quebec. These organisations and their impact will be further discussed in the summative evaluation.

Ultimately, a complete analysis of economy would require a meaningful analysis of cost per student and associated benefits to the economy, which is beyond the scope of the current study. Given the extreme diversity that exists between circumstances, a meaningful determination of cost per student will require significant expertise and analysis. For example, college tuition is generally lower than university tuition; graduate degree tuition is also typically higher than undergraduate; as well, married students and those with dependents require a completely different analysis of costs. Key informants indicated, however, that a breakdown of cost per student would not be particularly useful but instead, it would be more relevant to obtain information on how First Nations are maximising the resources allocated.

5. Evaluation Findings - Design and Delivery

The evaluation looked for evidence that the design of the post-secondary program provides a clear understanding of program activities and roles and responsibilities, as well as the extent to which activities, outputs and outcomes are being measured. It further looked for evidence that the delivery of the program is the most effective and efficient to ensure student success and value for money, as well as challenges with respect to program administration.

Significant concern was expressed that the current approach to funding results in allocations that are insufficient to meet demands and are not reflective of actual costs. Extensive analysis to determine actual costs, appropriate approaches to funding, and actual demand relative to resources is required to improve the current funding approach.

Reporting regimes for education do not currently meet the need for reporting on outcomes, nor provide a comprehensive understanding of costs relative to educational and labour market benefits, and therefore, do not meet requirements for basic accountability.

5.1 Design

5.1.1 Funding Approach

The current approach to funding post-secondary education has been cited by key informants and multiple sources of literature as being ineffective and no longer reflective of current cost realities. It has been further suggested that allocation methodologies used at INAC have created inequitable disbursements between regions, ultimately giving rise to significant variations in funding available for students.

Administration of the PSE program has been in the hands of individual bands since the early 1990's. Bands receive funding that has been flowed from INACHQ to INAC regions, and they allocate to their students based on the National Program Guidelines. Regions do not receive a fixed amount for post-secondary education; instead, HQ provides program funding for post‑secondary education as a component of each region's annual core budget, which since 1996-97, receives an increase of approximately two percent per year. This two percent increase to the overall budget does not meet the increasing costs of tuition and other expenses, such as cost of living and books, and it has been recommended by the Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Affairs that it be eliminated for the PSE program.[Note 24] In response to this recommendation, INAC stated, regarding funding, that "the responsibility for financing post-secondary education should be shared by learners and their families, according to their financial circumstances. It agrees that levels of support provided through INAC PSE programs should take into account the real needs of learners, but this does not mean trying to meet all of the costs they incur in pursuing post-secondary education. Instead, the Government will take a closer look at the overall efficiency of programming and ways to improve upon it."[Note 25]

In the regions, the allocation varies, sometimes considerably, from one region to the other. As stated in the recent INAC audit of the Post-Secondary Student Support Program, "in two of the regions visited, program allocations are based on the 18-34 age cohorts in each recipient First Nation and in the region as a whole. Another region allocates program funds based on the prior year's funded amounts, retaining annual program increases in a pool and allocating the funds to only those recipients that are able to demonstrate unfunded demands (wait-listed students). Lastly, another region allocates program funds based on their prior year's audited eligible expenditures and allows them to apply for additional funds from the pool of program funds that remains unallocated, assuming they can demonstrate demand."[Note 26]

5.1.2 Reporting

In order to assess performance, it is necessary to have relevant supporting data. This has been a weakness in the Department for many years, as noted in multiple audits, evaluations and external reports. The Department, in its 2009-10 RPP, explicitly states the lack of information necessary to assess student performance and grade progression as a key strategic risk in education. While a significant amount of work has been put into developing a performance measurement strategy, as well as an integrated database system (Education Information System), much is left to be done to improve INAC's performance record on collecting and analysing meaningful data.

As mentioned above, INAC is in the development phase of a new database system, which is intended to streamline and better utilise information from reports, store data in a "mineable" format to allow for complete analysis, use information from other databases to provide context on meaningful outcomes measurement (i.e., socio-economic and school infrastructure data), and enable timely reporting on results based on performance indicators to be developed in discussion with First Nations and other stakeholders. Additionally, the expectations are that this system will reduce and simplify data reporting burden; allow for data integrity measures throughout data collection; link financial information to program results; and provide timely reports on program management and performance measurement.

Currently, however, it is still very difficult to assess the extent to which outcomes have been met by students. While the evaluation team's preliminary search in FNITP showed that a significant amount of reporting was being collected, much of the information gathered falls short of what is necessary for meaningful outcomes measurement (for example, number of students enrolled). As has been reported in previous audits and evaluations, these reports do not provide the Department with a clear sense of how students are doing or whether their needs are being met. Documents reviewed and information from key informants suggest that there is a very inconsistent understanding within the Department as to what exactly is being reported, and that very little of it is being analysed or utilised for program or policy purposes by either regions or HQ. While some of this can certainly be attributed to a lack of human resources and turnover, there is also an issue of consistency in reporting (including a lack of understanding/guidance of how to complete reports, staff turnover, qualitative answers, electronic vs. paper forms to name a few) that makes reports difficult to roll-up. This results in a lack of analysis to define trends within the program. From a policy perspective, this is particularly problematic, as decision makers are not able to obtain the information necessary to make informed decisions.

For example, the large majority of INAC key informants were unable to ascertain whether learning outcomes had improved for Aboriginal post-secondary students. Though data shows that graduation rates have improved slightly over the past five years, the information currently collected by INAC does not provide any indication of where students go after they graduate, nor whether they proceed directly into to the labour force. However, given the fact that the funding envelope has remained relatively static over the past 15 years and that education costs have increased, any improvements in graduation rates would indicate ability at the local level to maximise resources, though there is currently no reporting to substantiate this finding.