Archived - Summative Evaluation of Consultation and Policy Development and Basic Organizational Capacity Funding

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 16, 2009

PDF Version (612 Kb, 93 pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Background

- 2.0 Overview

- 3.0 Evaluation Questions

- 4.0 Key Recommendations

- Action Plan

- Annexes

Executive Summary

Introduction

The Institute On Governance is pleased to submit the following report to the Audit and Evaluation Committee of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC). The report is on a summative evaluation of two of the Department's contribution programs that had similar objectives and recipients – contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development (C&PD) and basic organizational capacity of representative Aboriginal organizations program (BOC). The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and rationale, success and impacts, and cost effectiveness of both programs as well as the potential for synergy between the two.

The evaluation was conducted through a document and file review; interviews with INAC and other federal officials, experts and Aboriginal organizations; and case studies of three organizations, one Regional Office and one policy consultation. The evaluation covered the five year period from 2003/04 to 2007/08 and focussed more on the C&PD program given its size relative to the BOC program and the fact that it had not been evaluated since its inception. The major limitation in conducting the evaluation was the lack of consolidated performance information for both programs.

Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development

The objective of "Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development" is to provide support to Indians, Inuit and Innu so that the Department can obtain their input on all policy and program developments. Over the longer term this should result in better informed policy, improved relations, and support for INAC's policies.

The C&PD authority was extended in 2005 to March 31, 2010. Eligible recipients are Indians, Inuit and Innu individuals and related organizations. C&PD funding is provided on a project basis linked to a proposal or application. Program directors and regional directors have delegated authorities to receive and approve applications and are accountable for agreements, reporting and monitoring. Performance monitoring for the program as a whole has been defined but performance information is not being collected, assessed and reported annually.

C&PD is not the only project funding that is provided to some or all of the eligible recipients – for example, many of the recipients receive contributions to support claims and self-government negotiations. C&PD funding is also not the only authority that funds consultations and policy development – for example the Office of the Federal Interlocutor provides consultation and policy development funding to Métis and Non-Status Indian representative organizations through its contribution program authority.

The total amount of funding using the C&PD authority varies greatly from year to year depending on what consultations are held and how allocations are made. Actual expenditures range from a low of $34.6 million to a high of $64.4 million. There is an initial allocation to C&PD made at the beginning of the financial year, and this amount is amended as required throughout the year through reallocations from other program authorities.

The funding is divided into two components: a "base" amount and a "variable" amount. The base amount is allocated by INAC's Regional Offices and through the Intergovernmental Relations Directorate (IRD) and the Inuit Relations Secretariat (IRS) to support ongoing policy discussions on priority issues. This base amount is provided predominantly to regional Aboriginal representative organizations and to two National Aboriginal Organizations - the Assembly of First Nations and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Many of the Regional Offices and IRD and IRS combine the base amount with BOC funding and other project funds in order to support an agreed annual work plan for the organizations.

The "variable" amount of C&PD funding is linked to subject-specific and time limited consultations. These consultations have been related to constitutional, governance, human rights, and finance issues as well as sectoral policies related to education, economic development, water, and housing. Many of the consultations have been large scale – for example, consultations on Matrimonial Real Property On Reserve had a total budget of $10 million over several years - and may be initiated by different programs in Headquarters, primarily within Policy and Strategic Direction. The program director is responsible for providing the budget to reallocate to the C&PD authority.

Most of the C&PD funding is provided to First Nations and First Nation-related organizations. Inuit organizations receive a much lower proportion and other Aboriginal organizations an even lower proportion. Some funding has been provided to organizations representing off-reserve or non-status Indians or Métis. The Terms and Conditions of the C&PD authority include different terminology – i.e. status Indians, Indians on or off reserve, Aboriginal organizations – and there is a need to clarify the target groups and beneficiaries.

Aboriginal representative organizations have received over 75% of the total C&PD funds in the past five years. About two-thirds of the funding has gone to regional Aboriginal organizations and one-third to national Aboriginal organizations.

Contributions to basic organizational capacity

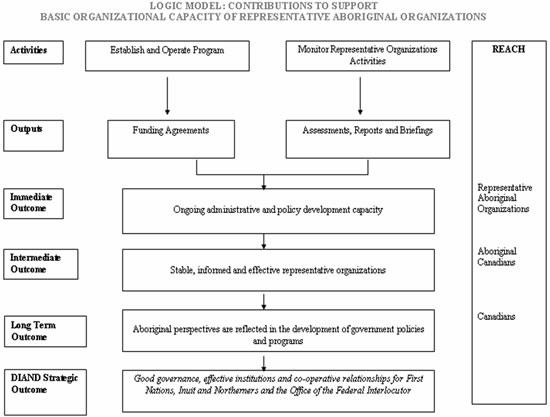

The objective of contributions to support basic organizational capacity of representative Aboriginal organizations is to build their ongoing administrative and policy development capacity so that they can become stable, informed and effective representatives of their constituents and ultimately Aboriginal perspectives are reflected in the development of government policies and programs.

Prior to 2007, core funding to status Indian representative organizations was provided by INAC and core funding to Inuit, Métis, non-status Indian, and Aboriginal women's representative organizations was provided by Canadian Heritage. As of 2007/08, INAC is responsible for providing core support to all Aboriginal representative organizations and does so through its Regional Offices and IRD, IRS, and the Office of the Federal Interlocutor.

The BOC authority was approved in 2007 and extends to March 31, 2012. Funding is provided through contributions based on work plans, rather than through grants. Eligible recipients are Aboriginal representative organizations at the national, provincial/territorial or regional level and national Aboriginal women's organizations. Recipients must be incorporated and provide evidence that their membership is restricted to a defined or identifiable group of communities or organizations; that they are mandated by their membership to represent or advocate on their behalf; and that they are not in receipt of other core funding from any other federal department for the purpose of maintaining a basic organizational capacity to represent or advocate for the interests of their members.

IRD has been assigned responsibility for preparing program reports and carrying out program reviews. The performance measurement strategy has defined performance indicators linked to immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes.

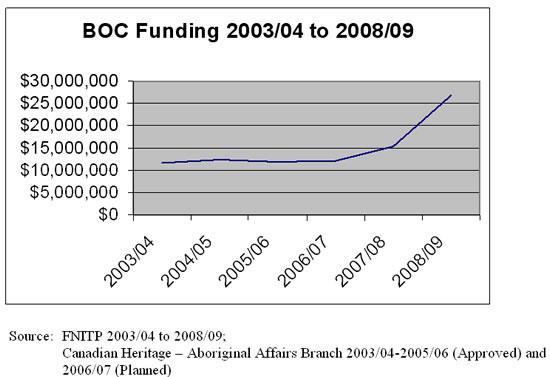

The total amount of BOC funding was stable at $12.6 million annually from 2003/04 to 2006/07. In 2007/08 it increased to $15.5 million, and in 2008/09 it increased again to $26.8 million. We were however told by INAC officials and recipients that the increase in BOC funding to First Nation and certain Inuit organizations was offset by a decrease in the "base" amount of C&PD funding – in other words, through a reallocation of funds between the two program authorities.

About two thirds of the BOC or core funding is provided to regional organizations and one-third to national organizations. First Nations' representative organizations have received the highest proportion of BOC or core funding followed by Métis and non-Status Indian representative organizations, Inuit representative organizations, and Aboriginal women's representative organizations. Core funding to the different Aboriginal groups has been linked to historical trends rather than populations and each recipient group is managed through different divisions within INAC. We did not hear of any rationale for allocating funds across the recipient groups or between national and regional organizations.

Findings, conclusions and recommendations

1. Contributions to consultation and policy development

1.1 Rationale and Relevance

We have concluded that the objectives of the contributions for consultation and policy development remain consistent with the Government of Canada's priorities and the Department's strategic objectives. The Government of Canada is committed to a partnership approach with Aboriginal peoples, communities and organizations; and this approach underlies all of the Department's strategic objectives.

The C&PD authority has primarily benefited First Nations. There is no longer a need to separately identify the Innu as they are now covered by the Indian Act. There has occasionally been a need to consult with other Aboriginal groups including non-status Indians, Métis and Aboriginal women.

We recommend that the list of eligible recipients be clarified and expanded to provide for all Aboriginal groups. This would reflect INAC's current mandate that covers all Aboriginal groups as well as the historical and recent use of C&PD funding, and would provide flexibility when engaging in consultations in the future on issues that have a potential impact on all Aboriginal groups.

The adequacy of support is a difficult question to answer because C&PD has a fluctuating budget. The "base" allocation is under pressure given caps on INAC's budget. Substantial amounts have been provided for subject-specific consultations.

More critical issues that were raised were the risk of consultation overload; the inadequate time provided for consultations; and the lack of sustainability of the project funding approach given the need to build consultation and policy development capacity.

We recommend that funding for consultation and policy development be more sustainable and less ad hoc and that there be fewer subject-specific consultations underway at any one time.

1.2 Success and Impacts

Over 400 Aboriginal organizations have been provided with the opportunity to participate in consultation and policy development activities over the past five years. These are predominantly First Nations' organizations. On the other hand, three quarters of the funding is provided to Aboriginal representative organizations and 40% of the recipients have received less than 1% of the funding.

We recommend that the use of C&PD funds be focussed on fewer recipients.

The reach of the C&PD funding in terms of individuals is not known because relevant information is not gathered, not reported, or not consolidated into a performance report for the C&PD authority as a whole.

We recommend that subject specific consultations should have clear objectives about who they are intending to reach, should select the most appropriate intermediaries, and should ensure that reporting is provided on who has actually been reached, and that a gender based analysis and gender disaggregated data should be part of these considerations.

The "base" allocation of C&PD funding has supported ongoing working groups together with core funding and other project funding. According to INAC officials and recipients, this has helped to foster and maintain a good working relationship between INAC and the recipient organizations.

The "variable C&PD allocation has been used for subject-specific consultations and according to INAC officials this has improved their understanding of the issues and concerns of Aboriginal peoples and communities and improved relations at the working level.

One aspect that is not dealt explicitly in the C&PD logic model is the degree to which C&PD funding improves the relationship between recipients and their constituents. Where C&PD funding has been provided on an ongoing basis, recipients are better able to set up processes and structures for engaging their own stakeholders. Where C&PD funding is provided on an ad hoc basis, recipients sometimes have had difficulty engaging their constituents.

We recommend that more frequent reviews be conducted of the relationship between INAC and Aboriginal representative organizations and other major recipients of C&PD funding; and of the relationship between recipients and their constituents. The latter should be conducted by the recipients themselves.

At the regional level, participation in consultations is related primarily to the communication of information or taking joint decisions on the implementation of INAC's programs. At the national level, participation is related more to the development of legislation, policies and programs. INAC officials indicated that they had been influenced by the consultations that were held. Recipients on the other hand expressed a great deal of frustration with both the approach of the government to consultations and with the outcome.

We recommend that large scale consultations should be assessed more rigorously in terms of their purpose, process, people involved, context, and outcomes and that best practices and lessons learned be captured and shared within and outside of INAC.

1.3 Cost Effectiveness and Alternatives

As indicated above, more sustainable consultation and policy development capacity is needed in key partner organizations as well as a more strategic approach and more rigorous assessment of the consultation process and outcomes.

The C&PD funding authority is being managed by the program directors and Regional Offices consistent with the terms and conditions with a very few exceptions in terms of the organizations or activities funded.

We recommend that performance monitoring of C&PD be improved in order to provide a clearer picture of what consultations the Department is engaged in, the approaches that have been taken, the organizations that have been involved, the impact on policy and best practices and lessons learned.

2. Contributions for basic organizational capacity of Aboriginal representative organizations

2.1 Rationale and Relevance

The objectives of BOC are also consistent with Government of Canada's priorities and the Department's strategic objectives. Aboriginal representative organizations are key partners for INAC and involved in all of INAC's strategic areas.

INAC officials, recipients and experts were in general agreement that there was a continuing need to support the basic organizational capacity of Aboriginal representative organizations. It is too early to judge where further changes are necessary. There were differing opinions about what an appropriate amount of BOC funding would be, how closely it should be linked to INAC's priorities, whether more funding should come from other sources including members, or whether the amount should cover minimum costs for a set of core positions and operations. There were also differing opinions about the allocation of the funding among the organizations.

BOC appears to have been implemented as intended although 2008/09 is the first full year of implementation and therefore it is too early to judge. There has been an increase in BOC funding in 2007/08 and 2008/09 due to the reallocation of funds from the "base" C&PD allocation. The transfer of responsibility from Canadian Heritage to IRD, IRS and OFI has taken place, INAC is of the view that management control procedures have improved, and recipients commented favourably about INAC's and OFI's management in comparison to Canadian Heritage.

It is not clear whether performance indicators related to the Performance Measurement Strategy have been incorporated into the funding arrangements with all recipients. It is also not clear where performance information will be collected, analyzed and reported across all Aboriginal representative organizations.

We recommend that the performance monitoring of BOC be improved in order to ensure that relevant performance information is collected, analyzed and reported by INAC for all Aboriginal representative organizations.

2.2 Success and Impacts

The historical timeline of Aboriginal representative organizations indicates that they have been very stable over the past decade. The achievement of administrative and policy development capacity cannot however be attributed primarily to BOC funding because it is a very minor portion of the total revenue of most of the organizations.

BOC funding covers some board, executive, finance and administrative costs but has not generally provided for policy capacity. Core costs are covered primarily by the administrative portion of project funding. This creates instability, reduces efficiency, and impedes the sustainability of communication and consultations with constituents.

The Aboriginal representative organizations receive a mandate from their constituents and are guided to varying degrees by the inputs from members. The degree to which they are effective in representing their members is not regularly assessed however.

We recommend that Aboriginal representative organizations be encouraged and supported by INAC to regularly conduct reviews of organizational effectiveness. We also recommend that membership and governance information be made publicly available on the organizations' websites to increase their transparency to their members and to the Canadian public.

None of the organizations depends on its members for financial support and few charge membership fees. Financial support from members improves the accountability relationship between members and their organizations and allows organizations to engage in activities that the Government does not support.

We recommend that Aboriginal representative organizations be encouraged to raise revenue from their members and that INAC consider providing an incentive for increasing the revenue raised from members, for example by providing matching funds up to a ceiling.

As indicated under the discussion of C&PD funding, there is no performance information on the degree to which Aboriginal perspectives are reflect in the development of government policies and programs and a difference of opinion between INAC officials and recipients. In addition, given the amount, it would be hard to attribute any impact to BOC funding.

2.3 Cost Effectiveness and Alternatives

As indicated previously, more basic organizational capacity and long-term funding for policy development and less ad hoc project funding would enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the organizations. This should promote the hiring of long-term policy staff, systems development, knowledge management, improved communications and support for regional affiliates. It should also promote more strategic management by INAC of the relationship with these organizations.

We recommend that more long term and sustainable funding for policy capacity and less project funding be provided to Aboriginal representative organizations. This appears to be happening to some extent in the past year with the shift of funds from C&PD to BOC by IRD, IRS and the Regional Offices.

We also recommend that INAC encourage and support the Aboriginal representative organizations to diversify their funding sources and reduce their dependency on the federal government. Alternative sources could include membership fees, provincial or territorial governments, the private sector, or non-profit organizations. Reducing financial dependency on the federal government could increase accountability to members, increase sustainability, and expand the range of issues that the organization could engage in.

3. Synergy between C&PD and BOC

There are similarities between the C&PD and BOC programs in terms of objectives and recipients. The programs have been managed jointly to a certain extent. An alternative would be to consolidate the two programs under one authority. The major barrier identified to consolidation is that C&PD has a larger number of recipients.

We recommend that there be one authority combining BOC and C&PD funding, with several streams to provide for different types of recipients.

Key recommendations

The conclusions and recommendations of the previous section can be summarized in three key recommendations:

- Consolidate funding authorities for consultation and policy development into one authority through an organizational rather than program approach that:

- has similar objectives and outcomes to C&PD and BOC,

- has multiple streams - basic organizational capacity funding for Aboriginal representative organizations; consultation and policy development funding for a broader range of Aboriginal organizations on specific issues; and capacity building funding;

- increases the proportion of basic organizational capacity funding in relation to project funding;

- is based on one work plan, one report, and one organizational assessment; and

- is linked to one performance measurement strategy and one evaluation.

- Improve strategic coordination and management of consultation and policy development, regardless of the program authority that is used to fund it, through:

- longer term agenda, fewer high priority issues at any one time, fewer intermediaries;

- more rigorous planning, management and reporting of major consultations; and

- the consolidation of outcomes, lessons learned and best practices.

- Review and clarify allocations across the different Aboriginal recipient groups or within each recipient group.

Gender Based Analysis

Although the Evaluation's Statement of Work did not include a Gender Based Analysis, we have reported to some extent on gender-related issues and information in this Evaluation Report and provide a summary of those issues and that information in this section.

Neither the C&PD nor the BOC Treasury Board submissions included a Gender Based Analysis despite the fact that INAC's Gender Based Analysis (GBA) Policy requires that the differential impact on men and women of proposed and existing policies, programs, and legislation as well as consultations and negotiations be considered by INAC officials. The opportunity to reinforce the GBA Policy itself through the terms and conditions for C&PD or BOC was therefore lost.

The objectives and outcomes of both programs are not gender specific and gender disaggregated performance information is not required for either program. With the consolidation of funding to Aboriginal representative organizations in INAC but in different divisions, there is no longer a distinct Aboriginal women's program.

C&PD funding for Aboriginal women's organizations is low in comparison to other Aboriginal representative organizations. Most of the C&PD funding has been provided to the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC), although there are a few regions (Alberta, Nova Scotia, and Quebec) that have provided C&PD funding to NWAC's affiliates.

BOC funding to Aboriginal women's organizations is also low in comparison to other Aboriginal representative organizations. Aboriginal women's organizations have historically been funded only at the national level and not at the regional level – unlike all of the other Aboriginal representative organizations.

We have made two key recommendations that specifically address gender issues:

- that subject specific consultations should conduct a gender based analysis when setting their objectives about who should be reached and how they should be reached; and reporting on who has actually been reached should include gender disaggregated data;

- that allocations to Aboriginal women's organizations should be reviewed in terms of the level of funding and support for their regional affiliates.

Section 1 – Background

1.1 Introduction

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) provides support to Aboriginal Representative Organizations, First Nation Band Councils and other Aboriginal organizations through two contribution programs:

- Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development (C&PD)

- Contributions to support the basic organizational capacity of representative Aboriginal organizations (BOC).

In the Treasury Board decision on creation of the BOC program (TB 833715, June 13, 2007), a summative evaluation was required to be undertaken in 2009 to cover both the BOC and the C&PD programs for efficiency purposes since the two programs have a large number of recipients in common. The Institute On Governance is therefore pleased to submit the following report on the summative evaluation of both contributions to the Department's Audit and Evaluation Committee.

1.2 Statement of Work

The objectives of the summative evaluation are:

- To evaluate the relevance and rationale, success and impacts, and cost-effectiveness of both programs;

- To evaluate the implementation of the BOC contribution program during its relatively short history with INAC;

- To identify issues, gaps in data collection and performance information processes, lessons learned, and best practices and provide strategic advice; and

- To identify conclusions and recommendations to improve both programs.

The focus of the evaluation is to assess whether the two programs allow for effective consultation with Aboriginal people for the purposes of developing policy and whether funding is achieving measurable results in a way that provides value for money.

The full Statement of Work is provided in Annex 1.

1.3 Evaluation Scope

The evaluation covers a five year period from 2003/04 to 2007/08 for both programs. Because C&PD has never been evaluated, we also looked at financial information from the previous five year period, 1998/99 to 2002/03, drawing on the Estimates and Public Accounts. Previous evaluations of core (i.e. BOC) funding have covered the period up to 2003/04 and the findings of these evaluations will be brought into the analysis. Allocations for BOC funding in 2008/09 will also be analyzed because it is the first full fiscal year of implementation of the new authority.

The evaluation focuses more on the C&PD program given its size relative to the BOC program; the fact that it has not been evaluated since its inception; and the fact that BOC is only into its first full year of implementation. Issues of synergy, duplication or gaps across the two programs are explored since they have similar objectives and similar recipients.

The evaluation looks at the policies, logic models, terms and conditions, program profiles and program files related to the two programs. It also considers other information that provides the context within which the two programs were implemented and that may have affected the achievement of the outcomes. It assesses the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the programs through qualitative and quantitative data; and triangulates the information across a number of sources. INAC and recipient perspectives are taken into account as well as those of other federal departments and experts who have a knowledge and interest in the evaluation issues.

The major limitation in conducting the evaluation was the lack of consolidated performance monitoring information, particularly for C&PD funding, summarizing the organizations, activities and outputs that were funded over the past five years. This was critical given the wide range of recipients and the diversity of activities funded. We therefore had to try and construct a picture of what activities had been funded through our interviews and the picture is far from complete. Few informants had the historical and detailed knowledge required to recall what had been funded over the past five years. Most of the recipients did not know what authority had been used to fund their activities.[Note 1] Many of the recipients received funding under several authorities for one work plan and therefore could not distinguish C&PD funding from other project and core funding.

This limitation could be addressed in future through better performance monitoring – an issue we return to in the sections on conclusions and recommendations.

1.4 Approach and Methodology

The evaluation was conducted from September 2008 to January 2009 in three phases:

Phase 1 Preparatory phase resulting in the evaluation work plan.

Phase 2 Data collection phase resulting in the presentation of preliminary findings and conclusions on 15 December 2008.

Phase 3 Analysis and reporting phase resulting in the draft and final evaluation reports.

Four lines of evidence were employed in the conduct of the evaluation:

- a document and file review;

- interviews with officials in INAC, other federal departments and experts;

- interviews with a number of recipients;

- case studies related to the C&PD and BOC funding.

All of the lines of evidence have been used to formulate a response to the issues and questions of the evaluation as outlined in the Evaluation Matrix (Annex 2).

Document and File Review

Relevant documents and information were gathered and reviewed including the following types of documents:

- Speech From the Throne, Budget Speeches, news releases

- Treasury Board Submissions, Departmental Reports on Plans and Priorities, Departmental Performance Reports;

- HQ and Regional Office procedures (as identified by interviewees from HQ and ROs);

- program profiles and expenditures for the five year time period from 2003/04 to 2007/08; financial information for the previous five year period from 1998/99 to 2002/03 for C&PD; and allocations for 2008/09 for BOC;

- selected application requests and reports;

- staffing levels and organizational structures within HQ and selected Regional Offices to administer the two contributions.

- INAC and Aboriginal organizations' policy documents on the legal duty to consult;

- organizational profiles, strategic plans and reports for the sample of Aboriginal organizations (obtained from organizational websites or interviewees);

- Census data and analysis and statistical research on Aboriginal groups;

- surveys of Aboriginal peoples;

- relevant reviews, evaluations and audits;

- current relevant studies or draft policies on consultation, capacity building or financial support;

- previous studies or policy documents;

- contextual information of relevance such as land claim, self-government, treaty, sectoral or other negotiations;

- history of the formation and dissolution of Aboriginal representative organizations over the past four decades.

A list of documents referenced in this report is provided in Annex 3.

Interviews with INAC, other federal officials and experts

We conducted interviews with the following federal officials:

- Officials from INAC Headquarters who are involved in the contribution programs including Policy and Strategic Direction (Intergovernmental Relations, Women and Gender Equality, Consultation and Accommodation, Strategic Policy), Office of the Federal Interlocutor, the Inuit Relations Secretariat, Governance Branch, and Lands and Trust Services;

- Officials from INAC's 10 Regional Offices;

- Additional officials from INAC (HQ and Regions) in relation to the five case studies;

- Officials from three other federal departments who provide policy and consultation support to the same recipients – Health Canada's First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), Aboriginal Policy Directorate in Human Resource and Social Development Canada (HRSDC); and Aboriginal Policing in Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness (PSEPC) Canada.

We also conducted interviews with five experts in Aboriginal governance, representation, policy development and capacity building in order to test out certain findings and conclusions prior to the analysis and reporting phase.

Interviews with Aboriginal Organizations

We selected a sample of 29 Aboriginal organizations to be interviewed. About half of the organizations have received both C&PD and BOC funding; and about half have received only C&PD funding.

To ensure that the sample was adequately reflective of the organizations who receive funding, a number of variables were considered. These variables included: the Aboriginal groups that are represented (First Nations, Inuit, Métis, non-Status Indians, and Aboriginal women); the amount of funding received; the regions where the organizations are located; and the size of the organization (small, medium and large).

The sample consisted of:

- All of the National Aboriginal Organizations – Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Métis National Council (MNC), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP), and Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC);

- A random sample of provincial/territorial First Nation organizations (PTOs) and MNC and CAP affiliates spread across the regions;

- One national urban Inuit organization and two regional Inuit organizations; and

- First Nations, Tribal Councils, and other Indian-administered organizations.

We contacted the organizations by telephone and provided an introductory letter and interview template. By the end of the data collection period, we had completed interviews with a total of 20 Aboriginal organizations. These included 10 of the 14 organizations receiving BOC and C&PD funding and 10 of the 15 organizations that only received C&PD funding. As mentioned previously, many of the organizations had not heard of the C&PD authority and therefore could not identify what activities had been funded under that authority. Interviews with these organizations were therefore of limited utility in terms of addressing questions related to success, impact and cost-effectiveness of the funding.

Case studies

We conducted five case studies across Canada. Three of the case studies were of organizations; one was of an INAC Regional Office; and one was of a specific policy consultation.

The three organizational case studies were selected from the interview sample and chosen to reflect C&PD and BOC funding allocations, Aboriginal groups and amount of funding as follows:

- A national representative organization that has received both BOC and substantial C&PD funding (over $200,000 in the last three years);

- A regional representative organization that received BOC and moderate C&PD funding; (between $25,000 and $200,000 in the last three years); and

- An organization that received a small amount of C&PD funding ($25,000 or less) and no BOC funding.

The organizational case studies looked at issues such as representation and accountability to membership; core (operating), policy development and consultation capacity; sources and application of funding from all sources; extent and quality of relationship or engagement over the past five years with INAC, other federal government departments, or other governments; lessons learned; and potential for improvement or recommendations for change.

The Ontario Region was selected as the regional case study because it is one of the three largest regions in terms of C&PD and BOC funding. A member of our team travelled to the region to conduct interviews with INAC officials and recipients and to review files. The regional case study looked at C&PD and BOC contributions and issues such as how the funding was allocated; who was eligible to receive funding; what the approval or rejection rate of applications was; what the perceptions of key stakeholders in the region are in terms of the degree to which they are consulted or engaged and the extent to which their input is taken into account in policy or program development; and what are the best practices and lessons learned.

Consultation on Matrimonial Real Property (MRP) on reserve was selected as the policy case study because it is fairly recent, completed and well documented. The policy case study was used to explore issues such as who is involved from the federal government and Aboriginal side in consultations and negotiations; what support is provided to which Aboriginal organizations to engage in the issue; what is the impact of that consultation on the policy that is finally developed; how could the consultations have been improved in terms of scope, range, support, or outcome.

We will use all of the case studies to illustrate certain points in greater detail throughout this report.

1.5 Outline of Report

This report provides an overview of the key findings, conclusions and recommendations from the evaluation. It is divided into four main sections:

| Section I | Background – this section which provides the statement of work for the evaluation, its scope, the approach and methodology used, and an outline of the rest of the report. |

| Section II | Overview – an overview of the historical context, recent developments, previous reviews and evaluations, and terms and conditions of the two programs as well as a profile of funding and recipients and examples of activities or expenditures supported. |

| Section III | Evaluation Questions – the key findings and conclusions and initial recommendations related to the rationale and relevance, success and impacts, cost effectiveness and alternatives of each program as well as the synergy across the two programs. |

| Section IV | Key recommendations for improvements to increase the effectiveness of the two programs. |

Section 2 – Overview

This section is divided into two sub-sections - one on the contributions to consultation and policy development and one on the contributions to basic organizational capacity. In each sub-section, we provide a brief background and context for each program, outline the terms and conditions, provide a profile of funding over the past five or ten years, and analyze the recipients and activities in a bit more detail.

2.1 Overview of Contributions to Consultation and Policy Development

Background and Context

The federal government began funding Aboriginal organizations for the purpose of consultation as early as 1964 in the lead up to the White Paper on Aboriginal Policy released in 1969. The White Paper galvanized Aboriginal organizations into action in opposition to its proposal to assimilate Indians into mainstream Canadian society and abandon the system of reserves.

In 1976, Cabinet approved consultations with Indians, Inuit and Innu[Note 2] as a matter of policy (Cabinet Decision 360-76), with a focus on the development of programs and services to improve the quality of life of Aboriginal peoples. In the 1980s, funding under the C&PD authority was used to support Aboriginal participation in Constitutional discussions and biennial Aboriginal Conferences from 1983 to 1987 to discuss the meaning and implications of Section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982 which recognized and affirmed Aboriginal and treaty rights.[Note 3]

In the 1990s, consultation with the Canadian public in general and with Aboriginal peoples and organizations in particular received an increasingly high profile. A Consultation Directorate was created in INAC in 1993 to provide support and guidance for consultation activities. This support included training programs, the identification of best practices, the provision of advice, involvement in financial support for consultation activities, and production of a National Consultation Framework. Around that time, the Department was reorganized, operations were decentralized to the regions, responsibilities were increasingly transferred to First Nations and Inuit governments, and the Consultation Directorate "effectively ceased to exist."[Note 4]

In 1995, C&PD funding was used to support the preparation and participation of Aboriginal groups, organizations and individuals in the hearings of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). The government's response to RCAP, Gathering Strength: Canada's Aboriginal Action Plan, re-confirmed the rationale for supporting representative Indian organizations and involving Aboriginals as partners in the design, development and delivery of programs and services affecting their lives and communities.[Note 5]

In 1995/96, a review of the Department's consultation practices was initiated. The review found that there were substantial consultation activities occurring at all levels in the department for different purposes – funded through core support, C&PD funding, and through various programs. Consultation was regarded as a sound management practice as opposed to a program in its own right. Headquarters tended to see consultations as subject specific and time-limited whereas regions saw it as a continuous process based on established working relationships.

The review also found that there was no explicit departmental policy or directive guiding consultation. On the one hand, this provided flexibility for the development of different strategies in the various regions and sectors to meet diverse needs. On the other hand, it meant that there was not a consistent set of principles and no sharing of best practices across the department.[Note 6] Suggestions from departmental representatives at the time to increase efficiencies in using consultation funding included the following:

- provide more structure to consultations;

- reduce any resource duplication at a departmental and First Nation level;

- use specialists to facilitate consultations;

- ensure consultation priorities and objectives are clear; and

- adhere to a reasonable schedule for the discussion of specific issues.[Note 7]

In 2004, the government re-affirmed its commitment to consult with Aboriginal peoples on legislative, regulatory, policy and programming developments that affect them (Aboriginal Peoples Roundtable, April 19, 2004). Political accords were negotiated between the Crown and each of the national Aboriginal organizations – Assembly of First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Métis National Council, Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and Native Women's Association of Canada – that committed the parties to work cooperatively on policy development according to the principles of "mutual recognition, mutual respect, mutual benefit, and mutual responsibility."[Note 8]

The October 16, 2007 Speech From The Throne re-emphasized partnership and working with Canada's Aboriginal peoples. In four of the five priority areas, specific reference was made to involving Aboriginal peoples and addressing their concerns.[Note 9] A Métis Nation Protocol was signed on September 5, 2008 to guide ongoing dialogue between the Government of Canada and the Métis Nation on priority issues.

Recent Developments

The preceding discussion relates to the more traditional concept of government consultation – i.e. an exchange of information, views and opinions with relevant stakeholders to improve the design, implementation and evaluation of legislation, policies, programs and other government initiatives and ultimately achieve better outcomes. While the decision to consult in these cases is discretionary, it is increasingly seen as a matter of good governance. The definition of consultation and the use of the C&PD program authority are almost entirely linked to this type of consultation.

INAC also has statutory or contractual obligations to consult under various statutes, comprehensive land claim and self government agreements or other contractual arrangements. The C&PD authority includes the beneficiaries of comprehensive land claims and self government agreements among its eligible class of recipients, and we found a few examples of C&PD funding to these groups. This type of consultation was not however a major focus for C&PD funding and there are other program authorities available for consultation or negotiation with certain treaty, land claim or self government groups.

Recently consultation has taken on yet another meaning for INAC and the federal government. In 2004 with the Haida and Taku River decisions[Note 10], the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that the federal and provincial Crown have a common law duty to consult, and, where appropriate, accommodate when Crown conduct may adversely impact established or potential Aboriginal and Treaty rights. This legal duty to consult differs from the more traditional good governance type of consultation in two key respects. First, it is directed at government action that affects constitutionally protected rights as opposed to government action that affects public policy programming in areas such as social development, post secondary education, economic development, housing, etc. Second, the duty to consult is a legally enforceable obligation rather than a matter of discretion.

Since November 2004, INAC, Justice Canada and 14 other federal departments and agencies have been working on the issue of the legal duty to consult. On November 17, 2007, the Government of Canada announced a federal Action Plan on First Nation, Métis and Inuit consultation and accommodation.[Note 11] The measures in the Action plan include the development of federal policy on consultation and accommodation. Interim consultation guidelines have been produced that include both legal and good practice guiding principles:[Note 12]

- Legal principles – honour of the Crown, reconciliation, reasonableness, meaningful consultation, good faith and responsiveness.

- Principles from consultation practice – mutual respect, accessibility and inclusiveness, openness and transparency, efficiency, and timeliness.

There are therefore three types of consultation – good governance or discretionary consultation; a statutory or contractual obligation to consult; and the legal duty to consult. There are common principles that would apply to all three types – i.e. the principles from consultation practice – and good governance consultation can provide a foundation for successful consultations from a statutory, contractual or legal basis.

Aboriginal Views on Consultation

According to the Assembly of First Nations, the Crown has a moral duty to consult when developing federal legislation or policy.[Note 13] The AFN argues that where the Crown has proceeded unilaterally, "First Nations have pursued litigation, media campaigns, political advocacy, and direct action to frustrate the Crown's intentions, sometimes quite successfully. This has cost far more money than the cost of any consultation process. The price of lost time and good will is incalculable."[Note 14] The AFN also argues that the legal duty to reconcile the sovereignty of the Crown can only be achieved through consultation at the earliest stages of law and policy development to ensure that First Nations' rights are not infringed.[Note 15]

Furthermore, the AFN points out that the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples calls for free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous peoples, including for the development of legislative or administrative measures which affect them and development activities on their lands. The UN Declaration is also supported by the Métis National Council, the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, and the Native Women's Association of Canada. The Government of Canada voted against the UN Declaration, partly because of concerns that this provision for consent could imply a veto.[Note 16]

First Nations have consistently taken the position that consultation between First Nations and the Crown must take place on a government to government basis and not through the AFN because the AFN is neither a national Aboriginal government nor an agent of the Crown.[Note 17] The AFN can however support and facilitate a First Nations-Crown engagement. In the AFN's experience, the following general elements are required for successful engagement:[Note 18]

- the engagement of First Nations' leadership

- national dialogue

- independent research and expertise

- clear mandate for change

- a joint principled policy process

Several First Nations have begun to develop their own consultation policies and protocols as part of comprehensive self-government agreements or as separate documents (e.g. Hul'quminum First Nation, Treaty 8 First Nations). The Federation of Saskatchewan Indians and the Quebec and Labrador Regional Office of the AFN have developed consultation guidelines related to all types of consultation. These guidelines encourage early interaction, respectful relationship building, recognition of inherent and treaty rights, and the engagement of First Nations in the decision-making process.[Note 19]

The Métis National Council has developed A Guide for Métis on Consultation and Accommodation (Fall 2007) to ensure that Métis are engaged, that appropriate Métis representatives are being consulted, that the right questions are being asked, that the results are being implemented properly, and that the process is adequately funded. Many of the Métis Nation's regional affiliates are also in the process of developing Métis-specific consultation models for local, regional and provincial levels.

There is therefore considerable agreement between the federal government and Aboriginal representative organizations about the need to consult from both a good governance and a legal perspective and on the principles that would guide such consultation. There is however some disagreement about when Aboriginal rights are affected. For example, in our policy case study First Nations were of the view that law making in relation to matrimonial real property could infringe on their Aboriginal and treaty rights whereas the Department of Justice concluded that there was no legal duty to consult.[Note 20] There is also disagreement between the federal government and Aboriginal organizations about the extent to which consent is required for policies and programs that affect Aboriginal people.

C&PD Authority

Treasury Board authority to provide consultation funds was first approved in 1978 (TB 757362). In 2005, the C&PD authority was extended for another five years to March 31, 2010 (TB 831952, March, 2005), conditional on the Department returning with a Departmental Results Based Management Accountability Framework/Results Based Audit Framework (Departmental RMAF/RBAF).

Because the Department achieved its priorities and objectives primarily through grants, contributions and other transfer payments and operated with more than 80 separate authorities at the time, INAC and the Treasury Board Secretariat agreed that the Department would consolidate its authorities, adopt a strategic risk-based approach to audits and evaluations, and develop an umbrella RMAF and RBAF to support the remaining authorities.[Note 21] Authorities were consolidated down to 48 in the Departmental RMAF/RBAF, but the C&PD authority remained as a separate authority.

The objective of "Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development" is to provide support to Indians, Inuit and Innu so that the Department may obtain their input on all policy and program developments. The authority is part of INAC's Operations activity and therefore supports effective program and policy development in all of the department's strategic outcomes.[Note 22] In this respect, the authority relates to good governance or discretionary consultation.

According to the Logic Model for C&PD (Figure 1, Annex 5), C&PD funding of research, meetings and discussions by the recipients should lead to policy and position papers and advice. As a result, INAC should obtain diverse viewpoints on a wide range of issues concerning programs and services for Indians, Inuit and Innu and the understanding of all parties should be improved. Over the longer term, better informed policy, improved relations, and support for policies should result.[Note 23] The evaluation issues are based on this logic.

The following recipients are eligible to receive C&PD support:

- Indians, Inuit and Innu individuals, on or off-reserve

- Indian Bands and Inuit Settlements

- District Councils and Chiefs' Councils

- Indian and Inuit Associations and Organizations

- Tribal Councils

- Other Indian and Inuit Communities

- Indian and Inuit Economic Institutions, Organizations and Corporations

- Partnerships or groups of Indians and Inuit

- Beneficiaries of comprehensive land claims and and/or self-government agreements with any group of Indians, Inuit or Innu

- Indian Education Authorities

- Indian Child Welfare Agencies

- Cultural Education Centres

- Indian and Inuit Co-operatives

- Boards and Commissions.

The maximum amount payable to any one recipient per year for any one project is $5 million. C&PD funding is provided on a project basis linked to a proposal or application. Program directors and regional directors have delegated authorities to receive applications for funding and approve them in accordance with the Terms and Conditions. These directors are accountable for negotiating agreements, defining deliverables, and establishing project reporting requirements as well as for ongoing monitoring of agreements and identifying and resolving any potential issues that may arise. Recipients are accountable to INAC for carrying out the agreed activities, reporting, maintaining appropriate financial systems and administrative records, and cooperating in evaluation or audit activities.

C&PD funding is not the only project funding that is provided to some or all of the eligible recipients – for example, many of the recipients also receive contributions to support the negotiation process for comprehensive, specific and special claims and self-government initiatives. C&PD funding is also not the only authority that funds consultations and policy development – for example, the Office of Residential Schools and the Office of the Federal Interlocutor provide consultation and policy development funding to their target groups.

According to the Performance Measurement Plan in the Departmental RMAF/RBAF, the following performance indicators are to be collected and assessed annually:[Note 24]

- Number of organizations, individuals or other eligible entities being funded;

- The annual amount of subject specific consultation funding by region and topic;

- The number and scope of legislative and policy initiatives being consulted upon;

- The number of reports, studies, briefings, advice and guidance provided to the Department by status Indians, Innu and Inuit and other stakeholders;

- Analysis of compliance with funding agreements; and

- The general level of satisfaction of Indians, Inuit and Innu and other stakeholders with the government's commitment to, and support of, the consultation and policy development process.

Data sources include the financial system, administrative records and files, annual program reports, information from the recipients, and periodic surveys to determine the level of satisfaction. Only significant consultation and policy development activities at the initiative or program level are to be reported in the Report on Plans and Priorities and the Departmental Performance Report.

In terms of monitoring and reporting, our investigations revealed that:

- recipients are reporting to INAC on activities and expenditures in accordance with contribution agreements although they may not be aware of the funding authority that has been used to support those activities;

- program directors are reporting to senior management and sometimes the Minister, Parliament or the Canadian public on individual subject-specific consultations in various ways according to the nature, scope and purpose of the consultations;

- Regional Offices are reporting on all funding to Provincial/Territorial Organizations (PTOs) in terms of the Interim Policy on Funding to Representative Status Indian and Inuit[Note 25] PTOs from 2005/06, and a consolidated report has been produced by IRD for 2005/06 and 2006/07, but the reports do not provide details of C&PD funding to all recipients or detail the types of consultations that have been funded;

- reports on the number, dollar amount and recipients of funding is available from INAC's financial system; and

- RPPs and DPRs have noted a few significant consultation initiatives over the past five years – for example, the RPP for 2008/09 refers to consultations on the duty to consult and accommodate.[Note 26]

On the other hand, we found that:

- performance indicators are not being collected and assessed annually;

- there is no annual performance report summarizing all of the activities that have been funded under the C&PD authority;

- no performance reporting expectations related to C&PD have been conveyed to program directors and Regional Offices; and

- no surveys have been conducted of the satisfaction of recipients and other stakeholders with the consultation and policy development process.

There is therefore a need for greater clarity about what information should be collected, reported and monitored for the program as a whole.

The TBS Submission did not include a Gender Based Analysis. INAC's Gender-Based Analysis Policy requires that all sectors and units the Department consider the differential impact on men and women during policy and program development and in consultations and negotiations.[Note 27] In our view, the authority that provides funding for consultation and policy development should reference this GBA Policy. Performance monitoring of the issues and organizations funded should include a gender-based analysis. Data on participants and surveys of stakeholders should also be gender disaggregated.

Profile of Funding

The costs of consultation and policy development approved in the Treasury Board submission for 2005/06 to 2009/10 are as follows:

| Vote 10 – Grants and contributions | 2005-2006 | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 and ongoing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contributions for the purpose of consultation and policy development | $30,604,000 | $29,847,000 | $24,470,000 | $24,470,000 | $24,470,000 |

| Source: TB 831952, 6 April 2005, p. 3. | |||||

The profile of funding over the past ten years in the Estimates and the Public Accounts is presented in the following chart with further details provided in Table 1, Annex 5.

This linear graph represents the actual and estimated funding for consultation and policy development (CPD) from 2003-04 to 2007-08. The graph contains two lines: one represents the budget, and the other, actual funding. The line that represents actual contribution expenses exceeds the line that represents budget.

These two lines show the amounts (in millions of $) for each period, from 1998-99 to 2007-08. The X axis (horizontal) represents the years, from left to right, from 1998-99 to 2007-08. The Y axis (vertical) represents the amounts (in millions of $) from $0 to $70,000,000, divided in increments of $10,000,000.

For 1998-99, the amount budgeted is $16,909,000, whereas the actual figure is $47,865,566. For 1999-2000, the amount budgeted is $22,064,000, whereas the actual figure is $64,369,920. For 2000-01, the amount budgeted is $17,657,000, whereas the actual figure is $57,863,021. For 2001-02, the amount budgeted is $13,457,000, whereas the actual figure is $39,975,274. For 2002-03, the amount budgeted is $13,957,000, whereas the actual figure is $34,625,748. For 2003-04, the amount budgeted is $15,524,000, whereas the actual figure is $36,855,249. For 2004-05, the amount budgeted is $31,610,000, whereas the actual figure is $46,540,726. For 2005-06, the amount budgeted is $24,570,000, whereas the actual figure is $46,482,953. For 2006-07, the amount budgeted is $31,287,000, whereas the actual figure is $54,808,068. Finally, for 2007-08, the amount budgeted is $24,824,000, whereas the actual figure is $39,800,703.

Actual expenditure has varied from a low of $34.6 million in 2002/03 to a high of $64.4 million in 1999/2000. The variance in total funding is primarily due to the number and size of subject-specific consultations that are funded in any year. This also explains the variance between the amount budgeted in the Estimates (which is provided in the September of the preceding year) and the amount reported in the Public Accounts (which are produced at the end of the year). Resource adjustments or reallocations may be made throughout the year to the Annual Reference Level Update (ARLU) to reflect senior management decisions on departmental priorities, including to the reference level for C&PD funding.

C&PD funding has been provided through various divisions in Headquarters and through INAC's 13 Regional Offices. Most of the Headquarters funding is through the Policy and Strategic Directorate. The Regional Offices receive an initial allocation for C&PD in their ARLU at the beginning of the year which is adjusted when subject-specific consultations are initiated by Headquarters that involve organizations in their region. Manitoba, Ontario and BC have had the largest share of the funding over the past five years, and the three territories the lowest share.

| Region/Headquarters | Total 2003/04 to 2007/08 | % Total |

|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | $44,656,402.30 | 19.33% |

| Ontario | $27,614,967.00 | 11.95% |

| BC | $26,820,247.00 | 11.61% |

| Saskatchewan | $16,540,352.81 | 7.16% |

| Atlantic | $11,358,290.04 | 4.92% |

| Alberta | $10,247,267.00 | 4.43% |

| Quebec | $5,057,085.00 | 2.19% |

| NWT | $3,771,067.54 | 1.63% |

| Yukon | $3,287,379.00 | 1.42% |

| Nunavut | $1,044,142.66 | 0.45% |

| Sub Total Regions | $150,397,200.35 | 65.09% |

| HQ Policy & Strategic | $61,875,959.00 | 26.78% |

| HQ Lands & Trust | $13,296,844.71 | 5.75% |

| HQ Inuit Relations Sect | $3,871,129.00 | 1.68% |

| HQ Northern Affairs | $797,306.43 | 0.35% |

| HQ OFI | $304,606.00 | 0.13% |

| HQ Treaties/Abor Gov | $268,603.00 | 0.12% |

| HQ SEPRO | $175,000.00 | 0.08% |

| HQ Corporate Serv. | $82,570.00 | 0.04% |

| Sub Total HQ | $80,672,018.14 | 34.91% |

| Grand Total | $231,069,218.49 | 100.00% |

| Source: FNITP 2003/04 to 2007/08. | ||

Recipients

By Recipient Group

C&PD funding was provided to a total of 261 recipients in 2007/08. The number of organizations and amount of funding across the different recipient groups (First Nations[Note 28], Inuit, Métis, Aboriginal Women, and Other Aboriginal Organizations) is provided in the following table:

| Recipient Groups | 2007/08 $ | No. of Orgs | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian Bands | 2,182,469.00 | 59 | 5.48% |

| Tribal Councils, Sectoral Councils | 3,603,808.35 | 26 | 9.05% |

| AFN and PTOs | 26,388,983.41 | 22 | 66.30% |

| Other FN Related Organizations | 2,835,598.00 | 13 | 7.12% |

| TOTAL FIRST NATIONS | 35,010,858.76 | 120 | 87.97% |

| TOTAL INUIT | 3,142,929.00 | 10 | 7.90% |

| TOTAL MÉTIS | 30,000.00 | 1 | 0.08% |

| TOTAL OTHER ABORIGINAL | 1,077,393.00 | 6 | 2.71% |

| TOTAL ABORIGINAL WOMEN | 539,522.00 | 4 | 1.36% |

| GRAND TOTAL | 39,800,702.76 | 261 | 100.00% |

| Source: FNITP, 2007/08. | |||

Most of the funding (88%) is provided to First Nations and First Nation-related organizations. About two-thirds went to the Assembly of First Nations and the 21 Provincial/Territorial organizations. Some Indian bands have been funded but the total number is small in comparison to the total number of First Nations (59 versus 615) and the amounts tend to be very small.

Inuit organizations are the next largest recipient group, having received close to 8% of the total C&PD funding in 2007/08. The amount misrepresents the trends over the past five years, however, because $2,501,000 in core funding for Inuit representative organizations in 2007/08 was provided under the C&PD funding authority. If that amount is deducted from the total, the proportion going to First Nations organizations would increase to close to 94% and the proportion to Inuit organizations would decrease to less than 2% of the total (refer to Table 2, Annex 5).

The focus on First Nations and Inuit is consistent with the list of eligible recipients under the C&PD authority. Some funding has also been provided to organizations representing off-reserve or non-status Indians (i.e. the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples and its affiliates). There is some confusion in the terminology used in the Terms and Conditions about the target groups and beneficiaries - sometimes Status Indians are specified, sometimes Indians on or off reserve, and sometimes Aboriginal organizations more generally.

Although there is no specific reference to Métis people or organizations, a little funding has been provided to them over the past five years. This has included the Métis National Council (MNC), the NWT Métis, and the Labrador Métis. The Office of the Federal Interlocutor's contribution program includes funding for the MNC and its regional affiliates (which do not include NWT Métis or Labrador Métis) for ongoing consultations and policy development on a bilateral or tripartite basis according to an agreed work plan. Additional funds would be needed for subject specific consultations outside of that agreed work plan. For example, the $30,000 in 2007/08 was provided for Métis women participation in the National Aboriginal Women's Summit.

There were also a very few instances where the C&PD authority has been used to fund other organizations that do not fit the eligibility criteria – other governments (provincial, territorial, or municipal), universities, or non-governmental organizations. Of a total of 255 distinct recipients from 2005/06 to 2007/08, only 6 were organizations that did not fit the criteria. We have no information about what activities were funded with these organizations.

There is therefore a need to clarify the targeted groups and to ensure that funding is limited to those groups. In our view, the targeted groups and organizations should be defined broadly as Aboriginal and not restricted to Indians, Inuit and Innu. This would reflect INAC's current mandate that covers all Aboriginal groups and organizations and provide the most flexibility. It would also reflect the historical use of C&PD funding for the participation of Aboriginal organizations in key developments (see previous section on Background and Context); the use of the C&PD authority over the past five years to fund consultations with non-status Indian, off-reserve, Métis and Aboriginal women's organizations on issues that affect all Aboriginal groups (see subsequent section on Examples of Headquarters funding), and the limitations on funding for consultations under other program authorities.

By BOC Recipients

Three quarters of C&PD funding over the past five years has been provided to organizations that also receive BOC funding (refer to list in Annex 6).

| Recipient | Total | % Total |

|---|---|---|

| AFN and PTOs | $155,230,057.90 | 67.18% |

| ITK and Regional and Other Inuit Organizations | $11,266,774.66 | 4.88% |

| MNC and Affiliates | $305,000.00 | 0.13% |

| CAP and Affiliates | $4,228,864.00 | 1.83% |

| Aboriginal Women's Organizations | $4,349,217.00 | 1.88% |

| TOTAL BOC RECIPIENTS | $175,379,913.56 | 75.90% |

| OTHER RECIPIENTS | $55,689,304.93 | 24.10% |

| GRAND TOTAL C&PD FUNDING | $231,069,218.49 | 100.00% |

| Source: FNITP 2003/04 to 2007/08 | ||

The breakdown of funding between BOC and other recipients varies across the different regions and different divisions within INAC Headquarters (Table 3, Annex 5). Policy and Strategic Direction, Inuit Relations Secretariat and the Regional Offices in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba have provided over 90% of their C&PD funding to BOC recipients.

Sixty to seventy per cent of the funding has gone to regional Aboriginal organizations over the past five years and 30-40% to national Aboriginal organizations (Table 4, Annex 5).

This bar graph represents the CPD (consultation and policy development) funding provided to national and regional representative Aboriginal organizations from 2003-04 to 2007-08.

The graph contains five bars (vertical). The bars are all proportionally separated, representing the percentage of funding among regional Aboriginal organizations and national Aboriginal organizations. The X axis (horizontal) represents the year, from 2003-04 to 2008-09. The Y axis (vertical) represents percentage of funding, from 0% to 100%. The axis is divided in increments of 10%.

For 2003-04, the national Aboriginal organizations funded 32.41% of the total budget for this period, whereas the regional Aboriginal organizations funded 57.69%. For 2004-05, the national Aboriginal organizations funded 40.94% of the total budget for this period, whereas the regional Aboriginal organizations funded 59.06%. For 2005-06, the national Aboriginal organizations funded 35.44% of the total budget for this period, whereas the regional Aboriginal organizations funded 64.56%. For 2006-07, the national Aboriginal organizations funded 38.50% of the total budget for this period, whereas the regional Aboriginal organizations funded 61.50%. Finally, for 2007-08, the national Aboriginal organizations funded 29.60% of the total budget for this period, whereas the regional Aboriginal organizations funded 70.40%.

In order to understand C&PD funding better, we will now look at some concrete examples of activities that have been funded.

Examples of Activities

Headquarters

Consultations and policy development activities funded through INAC Headquarters have been linked to the following legislation, policy, programs or initiatives over the past ten years or more. This list has been compiled on the basis of the document review and our interviews and is not a comprehensive list:

- Constitution Act, 1982

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (1995)

- Gathering Strength/Inherent Right (1998)

- FN Governance Act, Bill C-7 (2002/03)

- National Centre for First Nation Governance (2003-2005)

- Aboriginal Peoples Roundtable (2004-2005)

- Plan of Action on FN Drinking Water

- Matrimonial Real Property on reserve (2005-2008)

- Repeal of Section 67 of the Canadian Human Rights Act

- Legislation, policies and transitional funding for First Nation Tax Commission, First Nation Finance Authority, First Nation Statistical Institute (2005-2008)

- Mould in Housing Strategy

- Legislation on specific claims (2007)

- Indian Taxation Advisory Board preliminary work (2007)

- National Aboriginal Women's Summit (2008)

- Leadership Selection Reform (2007-2008)

- Indian Land Registry System (2008)

- Consultation and accommodation (2008)

- Education policies and programs – national FN educational policy framework, FN educational jurisdiction, special education network, joint working group on funding and allocation of education funds, research on the status of FN curriculum development

- Aboriginal economic development framework (2008)

- Overall approach to Inuit education

- Engagement of Inuit on Olympic policy and economic development

- Urban Inuit

According to our interviews with INAC Headquarters officials, to a large extent C&PD funding is provided for consultations that INAC has identified as a priority and set aside funds for. Headquarters may be responsive to unsolicited requests from Aboriginal organizations to some extent, particularly from First Nation or Inuit representative organizations that also receive BOC funding and provided that the request fits within INAC's priorities. There are some moves to jointly identify priorities, e.g. joint INAC-AFN working committees, and C&PD funding is used to support participation on these committees.

Most of the Headquarters initiatives are large scale consultations. For example, consultations on Matrimonial Real Property (MRP) On Reserve had a budget of $6.4 million in 2006/07 alone, and a total budget of about $10 million over several years.

The budget for the MRP consultations was approved in a Memorandum to Cabinet and a Treasury Board submission that identified that the C&PD funding authority would be used. $2.7 million was provided to both the AFN and NWAC to hold consultations across the country and the funds were transferred through the Intergovernmental Relations Directorate. $1 million was allocated through a call for proposals issued to other national or regional Aboriginal organizations not represented by NWAC or AFN. Amendments were made by HQ or Regional Offices to their comprehensive funding arrangements with the recipient organizations to include the funding for MRP consultations.

Regional Offices

INAC's Regional Offices receive an initial allocation for C&PD funding in their ARLU and plan and manage the use of these funds. In many Regional Offices, the initial allocation had not increased in the five years from 2003/04 to 2007/08. In addition, Regional Office budget increases have been capped at 2% per year for more than the past five years and allocations for education and social assistance have had to be increased. Regional officials therefore expressed a concern to us that they might have to reallocate the C&PD funding for other purposes in the not-too-distant future.

The different regional approaches to the allocation of the C&PD funds is outlined below, based on our interviews with regional officials and the financial tables provided. To varying degrees, Regional Offices use C&PD funds together with other funds to provide organizational support to PTOs and, to a more limited extent other organizations, based on work plans. The variation seems to depend on the situation in the region in terms of: the number of First Nations; the number of PTOs and independent First Nations not affiliated with a PTO; the total amount of funding available; and other factors.

- BC Regional Office

(27.35% to BOC Recipients)

The BC Region has 198 First Nations, many of which are quite small and a large number of which have no affiliation to a Tribal Council or a PTO. The Regional Office uses C&PD funding together with BOC funding to support the region's three advocacy organizations - the First Nations Summit, the Union of BC Indians, and the BC Assembly of First Nations. It also uses C&PD funding together with Professional and Institutional Development (P&ID) funding to support the region's organizations in the social, education, emergency services and financial management sectors. Other funding goes to individual First Nations and Tribal Councils. - Alberta Regional Office

(95.01% to BOC Recipients)

The Alberta Region's 44 First Nations are all members of the three Treaty Organizations - Confederacy of Treaty 6 First Nations, Treaty 7 Tribal Council, and Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta. The Regional Office channels C&PD funding to the three treaty organizations as mandated by the chiefs of the First Nations. Treaty women's organizations have also been funded. - Saskatchewan Regional Office

(92.08% to BOC Recipients)

All 70 First Nations in Saskatchewan, except one, are members of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians (FSIN). The Saskatchewan Regional Office has allocated most of the C&PD funding over the past five years to FSIN. Up to 2007/08, a small amount of C&PD funding was also allocated to the Tribal Councils in the region, but as of 2008/09 all of the C&PD funding goes to FSIN. The C&PD funding to FSIN is combined with core funding and other project funding to support the annual work plans of FSIN's various Commissions. Occasionally, but very rarely, an unsolicited proposal is also funded. - Manitoba Regional Office

(91.56% to BOC Recipients)

The Regional Office provides most of the C&PD funding to the three PTOs in combination with core funding and other capacity building funding. The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs represents 62 of the 63 First Nations in the province; Manitoba Keewatinook Ininew Okimowin represents 27 northern First Nations and Southern Chiefs Organization represents 33 southern First Nations. In the past couple of years, C&PD funding has also been provided to the Treaty Land Entitlement Committee Inc. that represents 20 First Nations negotiating additional reserve lands. Occasionally individual Indian bands or Tribal Councils are funded on a targeted basis, usually for program specific projects. - Ontario Regional Office

(76.95% to BOC Recipients)

Ontario's 134 First Nations are organized into four regional groups and one provincial organization of chiefs that represents the four groups plus independent First Nations. The Regional Office provides funding to the five PTOs in combination with core funding and other project funding and based on annual work plans. In addition, C&PD funding is provided to First Nations, Tribal Councils or other First Nation organizations on the basis of proposals that are received and the reallocation of funds from other authorities.

In the Ontario region, all funding for PTOs is recommended by a regional PTO steering committee and approved by the Regional Director General. Decisions are based on proposals and work plans submitted from the organizations and prepared in consultation with the PTO coordinators who have a direct and ongoing relationship with the PTOs. Requirements for the work plan are specified in the Interim Funding Policy for PTOs and the process emphasizes priority setting. Other C&PD funding outside of the PTO envelope is approved by a regional operations committee that reviews proposals against the terms and conditions of the authority and the availability of resources. - Quebec Regional Office