Archived - Summative Evaluation of INAC's Food Mail Program

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: March 31, 2009

PDF Version (566 Kb, 50 pages)

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

- 2.0 Methodology

- 3.0 Evaluation Findings

- 4.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

- 5.0 Management Response/Action Plan

- 6.0 References

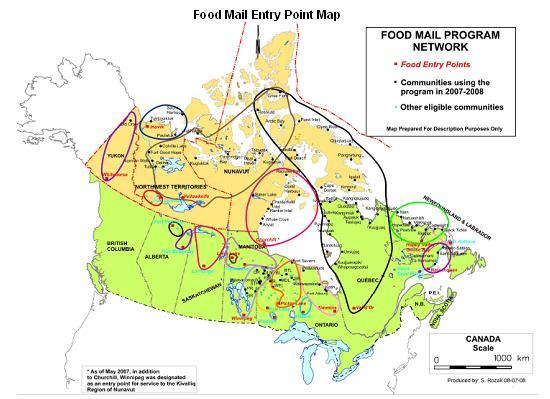

- Appendix A - Food Mail Entry Point Map

- Appendix B - Working Group Members

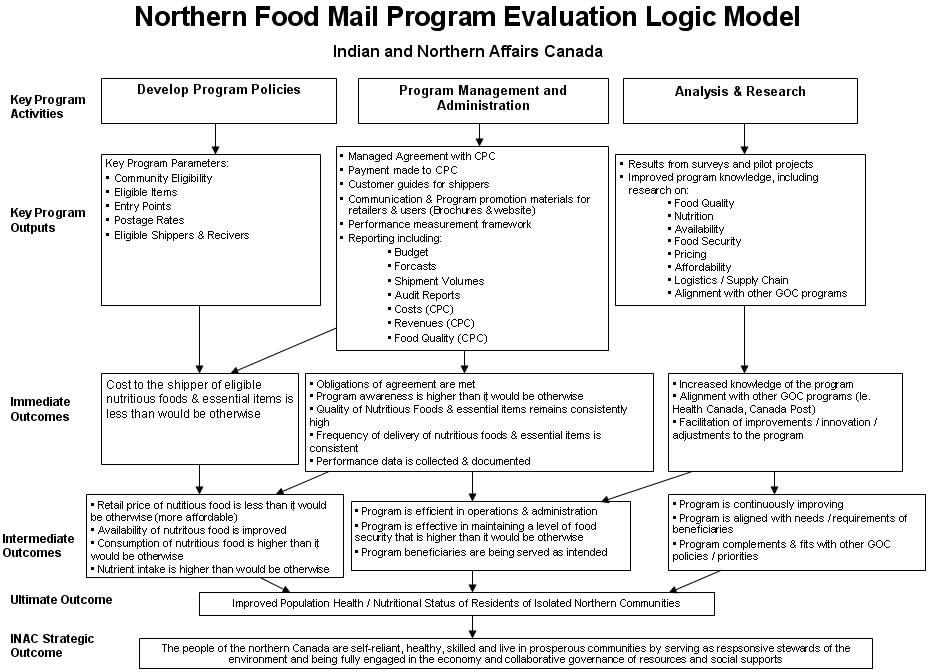

- Appendix C - Program Evaluation Logic Model

Acronyms

| AFN | Assembly of First Nations |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CPC | Canada Post Corporation |

| CHR | Community Health Researcher |

| DPR | Departmental Performance Report |

| FNIHB | First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

| FMP | Food Mail Program |

| HC | Health Canada |

| HFN | Healthy Foods North |

| INAC | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada |

| ITK | Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami |

| MB | Manitoba |

| NL | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| NPC | Northern Contaminants Program |

| NFM | Northern Food Mail Program (name changed to FMP) |

| NHFI | Northern Healthy Foods Initiative |

| NWT | Northwest Territories |

| NTI | Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated |

| NU | Nunavut |

| ON | Ontario |

| PMF | Performance Measurement Framework |

| QC | Québec |

| RDG | Regional Director General |

| RMAF | Results-based Measurement and Accountability Framework |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

Executive Summary

Introduction

The Food Mail Program (FMP) is a federal program that covers part of the transportation costs incurred when shipping nutritious, perishable food and other essential items to isolated northern communities that are not accessible year-round by road, rail or marine service. The program is managed by INAC, administered by CPC, and advice on the nutritional aspects of the program is provided by HC. The objectives of the FMP are to:

- Make nutritious, perishable food more affordable in isolated communities;

- Increase access to non-perishable food and other essential items in isolated northern communities; and,

- Promote healthy eating and a nutritious diet in isolated northern communities

The objective of the evaluation is to provide evidence on the extent to which the FMP is achieving its intended outcomes. The primary focus of the evaluation is to assess the effectiveness and impact of the FMP.

Methodology

Information used to inform the evaluation was gathered from multiple lines of evidence:

- Review of 72 files and documents

- Review of 71 sources of literature

- Statistical and econometric analysis

- Program incidence

- Program impact

- Cost effectiveness and impacts of program alternatives and complements

- 3 Expert Panels

- Panel #1 - Health/Nutrition/Food Security

- Panel #2 - Environmental Change &Traditional Food Sources

- Panel #3 - Community-based Food Issues

- 22 Key informant interviews

- 9 Community case studies

- Communities included:

- Repulse Bay, NU

- Inukjuak, QC

- Muskrat Dam, ON

- Kangiqsujuaq, QC

- Pauingassi, MB

- Cape Dorset, NU

- Nataushish, NL

- Cambridge Bay, NU

- Deline, NWT

- 174 interview/focus group participants

- Communities included:

- 3 Entry point case studies

- 24 interviews (including southern wholesalers, airline representatives, CPC-FMP inspectors)

FMP Evaluation Findings

The Food Mail Program Continues to be Relevant: The FMP increases access to nutritious, affordable foods in northern communities. Multiple lines of evidence support high levels of food insecurity, high rates of poverty, increases in diet-related diseases (e. g, obesity, diabetes), existence of nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron and vitamin D), poorer levels of general health, and decreases in the availability, safety and consumption of traditional/country foods. In the absence of a comparable program, the FMP provides a service that is essential to the physical, psychological and social well-being of northern communities.

However, the complexities of the program, its delivery system and the different relationships involved, along with the unique aspects of remote northern communities, make it challenging to understand in agencies outside those directly involved.

Limited Program Knowledge: INAC's communication about the FMP to community members is found to be lacking. The program was described as "invisible", "not widely publicized" and, as "flying under the radar". Community visits revealed little awareness about the program, the types of foods eligible for the program, and the benefits associated with the subsidy. Most residents (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) are unaware that a subsidy is being passed on to them through the retail stores. Those accessing the FMP through direct/personal orders only find out about the program through word of mouth from individuals currently placing orders in the south.

Limited Program Transparency: The roles and responsibilities of the numerous players (e.g., INAC, CPC, airlines, wholesalers, northern retailers, etc.) involved in the FMP process are not explicitly articulated. The lack of clarity limits accountability on the part of the players as no one is certain who is actually responsible for lost, damaged, spoiled or expired food items.

Program Reach: There is some question about whether the FMP is getting to those with the most need (e.g., Aboriginal people on social assistance) or those with the most money (e.g., RCMP, nurses and teachers). While direct ordering FMP items is the most cost effective way to access eligible foods (estimated saving of at least 25%), only those who possess a credit card are able to take advantage of this option. Findings from the statistical and econometric analysis suggest that food mail volume is correlated with income level, and that non-Aboriginal people may be consuming considerably more perishable foods (kg./person) than their Aboriginal counterparts, based on FMP shipment volumes and making allowance for food consumption by visitors and non-community residents in surrounding areas.

Reduced Food Costs: The FMP is providing eligible food items to northerners at prices that are more affordable than would otherwise be the case in the absence of the program. However, while food prices are reduced, they are still too expensive for many individuals who are underemployed or unemployed and dependent on social assistance. Increased subsidy rates for priority perishable foods (e.g., vegetables, fruit, eggs, etc.) in three pilot project communities resulted in significantly higher per capita volume shipments and presumably consumption of perishable items, suggesting further decreases in food costs leads to increases in healthy food purchases.

Food Quality Issues: The quality of FMP items is often compromised – spoiled or damaged – as a result of factors such as delays due to inclement weather and mechanical difficulties with the plane, length of time food spends on the tarmac, ineffective ground transportation (uncovered vehicles), and poor packaging/handling. Many items reach the north close to, or past, their expiry or best before date leading end users to question whether southern wholesalers are shipping goods to the north that could not be sold in the south.

Consumption of Nutritional Foods: Northern diets have changed over time, with a reduction in country food consumption and a generally high consumption of unhealthy high-sugar or high-fat foods of little nutritious value (e.g., pop, chips, processed foods). As a consequence, nutritional surveys have revealed decreased intakes of essential macronutrients (e.g., protein) and micronutrients (e.g., folate, calcium, and vitamins A, C, B6). Community case studies did show levels of variability in the northern diet with some individuals/families heavily dependent on country food while others are almost entirely dependent on store-bought foods. Food choice was found to be influenced by factors such as age, income level, availability of country foods, food quality, and personal preference.

Increasing Program Costs: FMP expenditures have steadily increased since 1999/2000, although postage rates have not increased since 1993 and the funding reference level has remained unchanged since 2002/2003. Yearly program shortfalls have been linked to factors such as increasing fuel costs and increasing food volumes.

Potential Program Complements: There is no evidence-based support to suggest that any identified alternatives (e.g., subsidies, program transfer, enhanced income support, other transportation options) would be more successful, cost effective, or have a greater impact on end users than the current postage subsidy. There exist a number of opportunities to complement the existing FMP (e.g., community freezer) and/or form synergies/linkages with other federal, provincial/territorial, regional and community-based initiatives (e.g., Northern Health Foods Initiative). Such an approach would assist the FMP in achieving its immediate, intermediate and ultimate program outcomes, and would improve the sustainability, effectiveness and impact of the program.

FMP Evaluation Recommendations

INAC should take the lead in developing a broad-based strategic approach aimed at building upon existing resources/programs to more effectively deal with northern food security issues from an integrated and multidisciplinary standpoint.

1. Work with federal, provincial/territorial, regional and community partners to develop a long-term Federal Food Security Strategy, which encompasses the Food Mail Program, along with other existing and future initiatives aimed at addressing issues related to health and nutrition in isolated northern communities.

2. Create a formal FMP Advisory Board composed of key stakeholders representing INAC, CPC, Heath Canada, and relevant national and provincial/territorial Aboriginal organizations to provide oversight, assist with the development of strategic objectives and priorities, and ensure community needs and perspectives are recognized.

3. Develop and maintain strong working relationships between the FMP and Health Canada programs with a nutritional component (e.g., Aboriginal Head Start, Diabetes Initiative, Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program) and community food-based programs such as day care centres and school breakfast and snack programs.

The proposed FMP Advisory Board should assist INAC in creating greater community awareness about the FMP and about the importance of proper nutrition.

4. Develop a formal communication campaign aimed at eligible communities that increases understanding and awareness of the FMP mandate, objectives, intended outcomes, administration, management and operations.

5. Work with Health Canada to develop a culturally and linguistically appropriate health promotion campaign aimed at northern Aboriginal people who are undergoing a shift in their traditional harvesting and consumption patterns as a consequence of global environmental/climate changes and changing food preferences in the younger generation.

6. Work with community-based leaders and health professionals to develop local, hands-on programs (e.g., community kitchens, recipe books) intended to teach local people about southern food preparation, nutrition content and integration with country foods.

INAC should provide overall leadership, with guidance from the FMP Advisory Board, to improve the program's efficiency and effectiveness through increased accountability and Aboriginal involvement.

7. Address food quality and service delivery issues by improving program transparency and accountability on the part of all players involved in the FMP process.

8. Engage Aboriginal organizations in reviewing and revising the FMP eligibility list to help ensure items are culturally appropriate.

9. Improve access to direct/personal orders for Aboriginal individuals and institutions (e.g., day care centre) so as to maximize their resources.

INAC, with guidance from the FMP Advisory Board, should identify existing programs and mechanisms to support local community initiatives aimed at reducing dependency on southern foods

10. Support local, sustainable complementary initiatives (e.g., community freezers, community gardens, inter-community sharing of traditional foods) that necessitate strong community involvement, development and control.

1.0 Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

1.1 Purpose and Structure of the Report

The final report outlines the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the impact evaluation of the department's Food Mail Program (FMP). This report provides a synthesis and analysis of all the data collected from the various lines of evidence used in this evaluation.

This report is structured as follows:

- Section 1: Introduction and Background to the Evaluation

- Section 2: Methodology

- Section 3: Food Mail Program Findings

- Relevance and Rationale

- Design and Delivery

- Accountability

- Effectiveness/Impacts

- Cost Effectiveness

- Alternatives

- Section 4: Conclusions and Recommendations

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Section 5: References

1.2 Objectives of the Evaluation

Accordingly, the evaluation will address the following program issues:

- Relevance and rationale

- Design and delivery

- Accountability

- Effectiveness/Impacts

- Cost effectiveness

- Alternatives

The evaluation findings, conclusions and recommendations are intended to improve the effectiveness and impact of the Food Mail Program.

While the FMP has undergone various audits, evaluations and reviews in the past, there have been no recent evaluations of the program. This evaluation will also help to inform the work that is being undertaken by internal and external reviews and will assist in program planning. In addition, it may help support work being planned for evaluations of other INAC programs with related themes and issues (e.g., Healthy Northern Communities).

1.3 Scope

This evaluation covers the ten-year period from March 1998 to March 2008. Some of the data included, however, are available for the following time frames:

- Nutritional Survey data covering the period from 1992 to 2005

- Retail Price Survey data covering the period from 1996-97 to 2007-08

- Northern Food Mail Shipment data, by community, for 1996-2008

- Canada Post Northern Food Mail transport cost and subsidy value, by community, for 2007-08

The total program spending from 1998 to 2008 was $331.7 million. Annual expenditures are illustrated graphically in Figure 1 of Section 3.5.

1.4 Background of the FMP

Food Mail, also known as the Northern Air Stage Program, is a federal program that covers part of the transportation costs incurred when shipping nutritious, perishable food and other essential items to isolated northern communities that are not accessible year-round by road, rail or marine service (INAC 2008a; CPC 2008). The intent of the FMP is to improve access to affordable nutritious food and other necessary items in remote communities where food costs would otherwise be too expensive for the majority of residents. The FMP is managed by INAC, which provides funding to Canada Post to cover some of the costs associated with transporting eligible items. Canada Post Corporation (CPC), in turn, contracts air carriers to ship the food mail to designated food entry points. A map of the various entry points is reproduced in Appendix A. Health Canada provides guidance to INAC on issues of food security and nutrition (INAC 2007a). Health Canada (HC) also contributes financially to certain components of the Food Mail pilot projects (e.g., Health Canada nutritional surveys conducted in isolated northern communities) undertaken to support FMP modifications.

The FMP offers services to approximately 140 isolated northern communities located in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon, Labrador, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. This represents a total population of approximately 100,000, the majority of whom are Aboriginal. The program enables retailers in these northern locales to sell essential perishable and non-perishable food and non-food items at a reduced postage rate. Table 1 highlights the current rates for the provinces, territories and specific communities. An additional charge of $0.75 per parcel also applies, regardless of size, contents or destination. FMP rates have not changed since July 1993.

| Destination | Eligible FMP Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Perishable Food | Non-perishable Food and Non-food | |

| Provinces | $0.80 per kg. | $1.00 per kg. |

| Territories | $0.80 per kg. | $2.15 per kg. |

| Aklavik, Tuktoyaktuk, Sachs Harbour, Paulatuk (served from Inuvik) | $0.30 per kg. | $2.15 per kg. |

Eligible items include: nutritious perishable food (e.g., fresh fruits and vegetables, milk, meat); non-perishable food such as canned food, cereal, pasta and baking supplies; and essential non-food items such as clothing, household supplies and personal care products. Non-nutritional foods such as soft drinks and potato chips, along with alcohol and tobacco, are not eligible for this subsidy (INAC 2007a).

Anyone in the eligible communities, including retailers, individuals and designated institutions (e.g., schools, daycare centres) can receive food mail. Most community members access food mail items through the retailers.

Food security and nutrition are important issues in isolated northern communities. Food security is a term that encompasses factors related to the nature, quality, and security of the food supply as well as issues of food access. It is a concept that can be examined at the level of the individual, household, community, region, or nation (Tarasuk 2001). Food security is said to exist "when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life" (Department of Agriculture and Agri-Canada 1998). The FMP helps to ensure that affordable nutritious foods are available to northern residents, thereby reducing the risk of food insecurity, which has been linked to negative nutritional, health, and social outcomes.

The FMP is one component of Canada's efforts toward achieving food security for Canadians, a commitment reflected in numerous international declarations and conventions that Canada has endorsed that recognize the right to food security. These include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Rome Declaration on World Food Security, and the World Food Summit Plan of Action of 1996.

In response to the Summit, Canada developed its Canada's Action Plan for Food Security was launched in 1998 (Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 1998). The Action Plan represents a long-term plan aimed at reducing food insecurity at both the national and international levels. The Plan involves all levels of government as well as NGOs, private institutions and groups. It builds upon international commitments as well as national economic, social and environmental programs and policies. The Plan, a working document, highlights ten priorities, one of which is the "Promotion of access to safe and nutritious food". This document notes that Aboriginal people, particularly in remote communities, experience "all or most aspects of food insecurity" as a result of a wide range of conditions.

1.5 Program Context

The FMP operates within a northern geographic, economic, social, and cultural milieu that is significantly different from that found in the south. The program is aimed at individuals living in isolated northern communities that are not accessible year-round by road, rail or marine service. The limited accessibility of these communities contributes to the high cost of food, housing, and fuel. The majority of people living in communities serviced by the FMP are Aboriginal, many of whom are living in difficult circumstances as a consequence of limited educational attainment, high rates of unemployment and/or underemployment, and high rates of poverty (often times depending on social assistance to help make ends meet). Many are forced to decide which basic need to spend their money on – food, shelter or clothing. Added to this are high levels of addiction occurring in many northern Aboriginal communities – substance abuse and gambling. The relatively quick transition from a traditional subsistence way of life to participation in the wage economy has compromised the overall health and well-being of individuals and communities. These factors all collide to create high levels of food insecurity in northern communities.

There are strong cultural differences that exist between northern Aboriginal peoples and southern non-Aboriginal populations. These cultural differences translate into variations in notions of diet, food selection, food preparation, food storage and food gathering. Northern Aboriginal cultures involve sharing and, as such, community members do not typically store food, shop for the week, or shop in bulk. This tradition is rooted in the practices of their ancestors, who were hunters and gatherers and took only what was needed from the land. As a consequence of decreasing trends in country food availability and accessibility, increasing numbers of Aboriginal people are now consuming a diet high in non-traditional foods. The relatively brief transition period from a primarily traditional diet to one heavily dependent on non-traditional foods, means that many Aboriginal people, specifically the Inuit, do not possess the nutritional knowledge about store-bought foods to discern between healthy and non-healthy food choices nor do they know how to safely prepare these foods.

The historic and cultural background of northern Aboriginal peoples must be taken into consideration when evaluating the effectiveness and impact of the FMP on northerners.

2.0 Methodology

In order to ensure that the evaluation of the FMP was comprehensive in nature, the evaluation team used multiple lines of qualitative and quantitative evidence. These included:

- Preliminary Consultations (to inform the development of the evaluation methodology);

- Document and File Review

- Literature Review;

- Statistical and Econometric Analysis (including a cost effectiveness analysis review of potential program alternatives and complements);

- Expert Panels;

- Key Informant Interviews;

- Community Case Studies; and

- Entry Point Case Studies.

Such an approach allowed for the triangulation of results, thereby improving the reliability and validity of the overall evaluation findings.

2.1 Development of the Evaluation Framework and Methods

The evaluation was structured around the need to address the following FMP issues:

- Relevance and Rationale

- Design and Delivery

- Accountability

- Effectiveness

- Cost-Effectiveness

- Alternatives [Note 1]

For each issue, relevant questions were developed to help fully explore that aspect of the FMP.

2.2 Preliminary Consultations

The evaluation team carried out preliminary consultations with five key FMP officials from INAC, Canada Post Corporation (CPC) and Health Canada First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB). The purpose of the consultations was to:

- Refine evaluation issues and questions

- Identify existing performance indicators

- Identify potential data sources

- Identify potential expert panel and key informant participants

Additionally, members of the evaluation team attended an evaluation working group meeting (October 24, 2008) in order to help refine the list of communities selected for case study analysis (refer to Appendix B for a listing of the FMP evaluation working group members).

The preliminary consultation activity began with the identification of key FMP stakeholders along with contact information for each identified individual. The evaluation team developed an invitation letter and a set of preliminary consultation interview questions. The evaluation team then contacted each individual to schedule a date/time for the interview. Some interviews were conducted in-person and others over the phone.

The primary intent of the preliminary consultations was to gather information that would assist in the development of the Detailed Methodology Report and Work Plan.

2.3 Logic Model

The evaluation team developed a FMP evaluation logic model (refer to Appendix C). The logic model was intended to guide the evaluation by articulating the stages of the FMP and identifying measurable outputs and outcomes. More specifically, the model identifies the linkages between the FMP activities (program policy development; program administration; and policy analysis and research), key program outputs (e.g., postage rates, managed agreement with CPC, documentation of research project findings), and the intended immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes of the program.

2.4 Document/File and Literature Reviews

2.4.1 Document and File Review

The document and file review was designed to assess a broad range of internal documents and files in order to demonstrate a breadth of information on the evaluation issues spanning the last ten to fifteen years. More specifically, the review was intended to help build an understanding of the FMP's history, objectives, and operations.

The evaluation team worked closely with INAC officials in compiling all available documentation. Evaluation team members were invited to review existing documents/files available at INAC headquarters. After briefly reviewing the available materials, the evaluation team determined the documents required for the evaluation. The Evaluation Manager then forwarded on hard and electronic copies of the identified documents to the team. The Evaluation Manager also provided the team with FMP-related website links in which pertinent materials could be downloaded.

Documents reviewed included program guides, research and reports, program eligibility criteria, draft RMAF, program audits, and internal documentation as provided. In addition to documents provided by INAC, materials from organizations representative of stakeholders in northern communities such as Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) were also consulted.

2.4.2 Literature Review

The literature review entailed an examination of a broad range of literature relating to key issues associated with the evaluation of the FMP. The review addressed the topic of northern food security, nutrition and health through an examination of literature on traditional and non-traditional (food mail and non-food mail foods) food sources. The review allowed the evaluation team to speak to the continued need (rationale) for the FMP. The findings help support evaluation-based discussions of more local options to food insecurity in the north.

Much of the literature was provided by INAC, although additional literature was identified through internet searches conducted by the evaluation team.

An INAC internal review of the FMP involved an extensive review of the literature on existing domestic and international alternatives to the FMP. As a consequence, much of the background material on the FMP and potential alternatives had already been examined in depth.

2.5 Statistical and Economic Analysis

This line of evidence involved two types of analysis:

- Statistical and Econometric

- Cost Effectiveness

2.5.1 Statistical and Econometric Analysis

The statistical and econometric analysis examined program incidence regarding who benefits from the FMP subsidy and estimated the program's impact on nutritious food prices and consumption in remote northern communities. The analysis also examined the extent to which there is evidence to support the hypothesis of full subsidy pass-though in northern communities.

Table 2 describes the statistical and econometric methodologies used to address some of the key evaluation questions.

| Evaluation Questions | Approaches |

|---|---|

| 1. Program Incidence: Who benefits from the FMP subsidy in remote Northern communities? |

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Per Capita FMP-Perishable Food Shipments Relative community FMP consumption; using community per capita shipments of nutritious perishable food (annual kg. per person). Canada Post (confidential data) on FMP volume shipments 1996-97 to 2007-08 (12 years for about 80-90 communities). Community population for Census 1996, 2001, 2006 and inter-census estimates based on interpolation or extrapolation. Other community socio-economic variables from Census data. Pooled (i.e. cross-sectional and time series) analysis at the community level with various socio-economic variables. |

| 2. Program Impact: a. Does the FMP subsidy result in proportionally lower nutritious food prices for remote Northern communities? |

Matched-Item Product Pricing: Using Northern Food Basket pricing data to compare communities (relative to their entry points) for selected non-eligible product items likely shipped by air to selected FMP-eligible product items. Northern Food Basket price surveys available for two years (since 2001) for up to 43 communities and 9 entry points. A sample of 17 communities and 7 entry points was selected. Canada Post (confidential data) on FMP costs and required subsidy available for 2007-08. (specific to sub-question a.) |

| b. Does the FMP subsidy promote nutritious food consumption? | Three Pilot Community Price Reduction Comparison Analysis applicable to three pilot communities (Kugaaruk, Kangiqsujuaq, Fort Severn) compared to similar communities in their region. Using community per capita shipments of nutritious perishable food (annual KG per person) and Northern Food Basket pricing data to compare communities (relative to their entry points) for 'priority' and 'other' perishable foods and non-perishable foods. Three time periods studied, looking at dynamic changes over time (relative to other periods and other communities): Baseline: six year period (1997-98 to 2001-02) prior to the start of the pilot program; Initial Pilot: two year period (2003-04 to 2004-05) immediately after the start of the pilot program; and Later Pilot: two-year period (2006-07 to 2007-08) several years after the start of the pilot program (roughly 2002-03). Uses Canada Post (confidential data) on FMP shipments. (this addresses sub-questions a. and b.) |

| c. Does the FMP subsidy support a healthy diet and positive health outcomes? | Review and Synthesis of Nutrition Survey Results Review and synthesis of relevant studies involving nutrition surveys for 5 communities and data for the entire Quebec-Nunavik region. These studies report on food and nutritient intake from 24-hour recall and food-frequency questionnaires. The study data and results can be further analyzed with a narrowly focused view on whether there were significant changes in food consumption as a result of the FMP. The studies also looked at associated health outcomes. Additional data can be brought to bear using community per capita shipments of nutritious perishable food (annual kg. per person) and Northern Food Basket pricing data to compare communities (relative to their entry points) for perishable and non-perishable foods. Uses Canada Post (confidential data) on FMP shipments. (addresses sub-questions b. and c.) |

2.5.2 Cost Effectiveness Analysis

The aim of the cost effectiveness analysis was to provide a preliminary assessment of possible alternatives to the FMP and their potential associated costs and impacts on outcomes. The analysis involved a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches including key informant consultations with INAC officials at headquarters, basic analysis of FMP costs and revenue trends, and a review of the literature relating to alternatives and costs.

More specifically, the cost effectiveness analysis considered historical trends in program costs and revenues, international equivalents of food mail programs in Australia, Alaska and Greenland, potential complements and their costs to the FMP, including hunter support, country food stores, storage and freezing facilities, agriculture initiatives in northern Canada and the U.S, other initiatives including, partnerships with other levels of government, businesses/NGOs and local programs, retail price competition, price information and consumer protection, food price signage, and finally, alternatives to the FMP such as, health food subsidies and promotion, U.S food stamps and Kativik food coupons, direct provision of food packages in the U.S and Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador, retail store subsidy and airline subsidy.

2.6 Expert Panels

The intent of the panels was to provide expertise and insight related to the current and future state of knowledge in the areas of health, nutrition, northern food security, traditional/country food harvesting and consumption, environmental contaminants, climate change and community-based perceptions of food security, as they relate to the FMP.

Three expert panels were conducted in January and February 2009. The panels focused on the following topical areas:

- Expert Panel #1 – Health/Nutrition/Food Security in the North

- Expert Panel #2 – Impact of Environmental Change on Traditional/Country Food in the North

- Expert Panel #3 – Northern Aboriginal/Community Food Access and Availability Issues

Preliminary consultations with FMP working group members and suggestions from the INAC evaluation manager, the evaluation team and key informant interview participants resulted in the identification of expert panel participants. Potential discussants were contacted and asked to participate.

Panel participants represented the following departments/organizations/academic institutions:

- Health Canada

- INAC

- Environment Canada

- Northern Contaminants Program (NPC)

- Arctic Health Research Network

- Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK)

- Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI)

- University of Northern BC

- Trent University

Each expert panel comprised three or four experts, with a total of 11 participants taking part. The sessions were scheduled to be 2.0 hours in length with most panelists participating by teleconference. Specific sets of questions were prepared for each of the three panels.

2.7 Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews were conducted from January – March 2009. A total of 22 individuals participated in the interview process. Key informants include representatives from the following:

- INAC Senior Management (e.g., RDGs)

- INAC Food Mail Program Management and Review Personnel

- CPC

- Health Canada (e.g., FNIHB)

- Provincial/Territorial Government (e.g., NU, MB)

- ITK and AFN

- Academic Institutions

The intent of the interviews was to gather knowledge, perceptions and opinions about the following evaluation themes: relevance and rationale; design and delivery; effectiveness; cost effectiveness; alternatives; and, accountability.

Preliminary consultations with FMP working group members and suggestions from the Evaluation Manager and the evaluation team resulted in the identification of key informant participants. Potential interviewees were contacted and asked to take part. Interviews were conducted in-person and by telephone. In one instance, interviewee responses were emailed to the team.

2.8 Case Studies

Case study research helps to increase our understanding of a complex issue and can add strength to what is already known through previous research. Case studies emphasize detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships. A key strength of the case study method involves using multiple sources and techniques in the data gathering process. The information collected is typically primarily qualitative, but it may also be quantitative. Tools to collect data include: interviews, focus groups, document review, and on site observation.

The rationale for using the case study approach was to spend a concentrated amount of time in the communities (2-4 days) and entry points (1-1.5 days) to maximize data collection.

2.8.1 Community Case Studies

The community case studies were conducted to determine the extent to which the program is achieving its objectives and to better understand the impacts of the program on users. The community case studies primarily addressed the evaluation themes of design and delivery and effectiveness, although there were questions focused on relevance and rationale, cost effectiveness, and alternatives.

Input obtained from the evaluation working group and the Evaluation Manager, as well as the evaluation team, resulted in the identification of potential case study community locations. Final selection of the sample was decided upon by the Evaluation Manager. An alternate list of communities was also developed as a "back-up" in the event that the evaluation team was not granted permission to enter the selected communities.

The selection of communities was guided by the following criteria:

- Geographic location by province/territory

- Variety of entry points

- Shipping volumes

- Not a Food Mail Review selected community

When conducting case studies in Aboriginal communities (or communities composed primarily of First Nations or Inuit peoples), it is important that the intent of the evaluation, the evaluation activities being carried out, and the types of community stakeholders to be involved in the evaluation are clearly communicated to the community leadership and to the community members as a whole. Initial contact with each community was in the form of an introductory letter sent by INAC to the community Mayor, Chief and Council, or Band Manager. This was followed up by phone calls to key individuals in the community by the evaluation team.

A total of nine communities were selected and case studies conducted between the weeks of December 1, 2008 and February 8, 2009 (refer to Table 3). A team of two evaluators participated in each community visit: each team had a minimum of one (and in most cases, two) senior evaluators with extensive experience in conducting consultations in Aboriginal communities.

| Case Study Community Name | Date Case Study Community Visit was Conducted |

|---|---|

| Repulse Bay, NU | Week of December 1, 2008 |

| Inukjuak, QC | Week of January 12, 2009 |

| Muskrat Dam, ON | Week of January 12, 2009 |

| Kangiqsujuak, QC | Week of January 19, 2009 |

| Pauingassi, MB | Week of January 19, 2009 |

| Cape Dorset, NU | Week of January 26, 2009 |

| Nataushish, NL | Week of February 2, 2009 |

| Cambridge Bay, NU | Week of February 9, 2009 |

| Deline, NWT | Week of February 9, 2009 |

During the community visit, a number of data collection methods were employed to allow the team to collect as much program data as possible in the allotted time:

- Face-to-face individual/group interviews;

- Focus group discussions;

- Document/file review [Note 2]; and

- On-site observation.

In a few instances, when key informants were unavailable during a community visit, telephone interviews were carried out after the identified study period.

Interviews and focus groups were conducted with community members representing the following:

- Northern retailers

- Health care professionals (nurses, medevac staff, CHR)

- School principals, cooks and breakfast/snack program managers

- Daycare centre directors and kitchen staff

- Restaurant/Hotel managers

- Airline representatives

- Residents accessing food mail items through the community retailers

- Residents accessing food mail items through southern wholesalers (teachers, nurses, RCMP)

- Others (Mayors, Council members, Landholdings Corporation representatives, Hunters and Trappers Association representatives, Community caterer, Regional government representative, Postmaster, Aboriginal Head Start Program Coordinators Treatment Centre Coordinator, FMP Coordinators (hired by airline), Family House Representative)

Over the course of the nine community case study visits, 174 individuals participated in interviews and focus group discussions. In some instances, interviews were scheduled prior to entering the community and in others, they were set up while there.

2.8.2 Entry Point Case Studies

The intent of the entry point studies was to gather information pertaining to quality control, packaging and shipping of FMP eligible items. The site visits also provided the opportunity to observe the food mail transportation and inspection processes. The entry point studies were conducted to assess evaluation issues, particularly those related to program design and delivery, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Evaluation themes including relevance/rationale and alternatives were addressed but not examined to the same degree as the other issues.

The entry point locations were selected by the Evaluation Manager in consultation with the evaluation working group and the evaluation team. Three entry point case study locations were chosen: Yellowknife, Val d'Or and Winnipeg. Entry point visits were conducted from December 2008 to February 2009.

With the assistance of the CPC Food Mail Coordinator, key informant interviewees were identified for each of the three entry points. Potential participants were contacted and asked to take part in the interview process. A total of eight individuals were interviewed at each location (some in-person and some by telephone). A total of 24 entry point interviews were conducted, eight in each site.

The Yellowknife and Winnipeg entry points involved site visits that lasted from a day to a day and a half. During that time, key informant interviews were conducted with airline representatives, wholesalers and Canada Post-FMP personnel. The Val d'Or site visit took place after the interviews were carried out by telephone. This occurred because of the constrained evaluation timelines, combined with other logistical factors, which made it next to impossible to coordinate a satisfactory number of interviews over a day and a half period. Thus, the evaluators spoke with airline representatives, a number of southern wholesalers, and CPC-FMP staff associated with the Val d'Or site to obtain sufficient information to enable a good understanding of the issues, and followed this up with a visit to the site for an inspection of the operations. This approach enabled a comprehensive review of the entry point.

3.0 Evaluation Findings

3.1 Rationale and Relevance

3.1.1 Need for the Program

The evaluation found strong evidence and overwhelming agreement that the FMP fills a need now and in the future. The FMP is described as an "essential service" since it provides food which is considered a basic need. Because of the program, isolated, northern communities are able to access healthy, nutritious food at a reduced cost. Currently, there is no other way to provide southern, nutritious foods that are affordable and accessible to northerners. The discontinuation of the FMP would have an enormous impact on food costs that are already considered too high for many Aboriginal families. It is estimated that people would pay at least two to three more for food items without access to the FMP. Only high-income earners - primarily those from the south (e.g., nurses, teachers) – would be able to afford to purchase nutritious foods. Those unemployed and dependent on income assistance – primarily Aboriginal people - would be forced to spend all of their monetary resources on food, leaving no available income for spending on other necessities. Multiple sources of evidence support the fact that an increase in food costs for those on limited incomes, and already experiencing food insecurity, would be detrimental to their health and overall well-being.

3.1.2 Factors Supporting High levels of Food Insecurity in the North

Food insecurity refers to the "…inability to acquire or consume an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so" (Radimer et al. 1992). Factors supporting high levels of food insecurity in the north include: high rates of poverty in northern communities due to high levels of unemployment and limited educational attainment; high cost of store-bought food; increased costs associated with hunting country food (e.g., vehicle, fuel, hunting supplies); shift from subsistence way of life to wage-based economy resulting in little time for hunting and a loss of knowledge and skills pertaining to the harvesting and preparing of country food; larger family sizes; high proportion of the population under 18 years of age and particularly vulnerable to food insecurity; social factors such as addiction (e.g., gambling, drugs, alcohol); changes in consumption patterns of traditional foods (decreased dependence on traditional food and increased dependence on store bought food); limited knowledge about what constitutes a healthy, nutritious diet and thus leads to poor food choices (high calorie, low cost foods); limited availability and poor quality of store-bought food; and the effects of climate change (e.g., decreasing availability of, and accessibility to, traditional food sources).

Food insecurity was described by key informants and expert panelists as having a negative impact on nutrition, physical and psychological health, and social/community well-being of northern populations. These negatives outcomes include:

- Nutrient deficiencies (e.g., low iron intake during child development leads to decreased intellectual capacity)

- Diet-related diseases (e.g., obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dental caries)

- Poorer health overall (based on general indicators)

- Increased stress, anxiety and worry associated with not being able to feed one's family

- Decrease in overall level of success for children at school and adults at work (lack of concentration and energy due to lack of nutrient intake)

- Loss of culture (decreased access and availability of country foods leads to inability to share foods leading to decreased social interaction and decreased mental health)

- Decreased community participation (as people become preoccupied with getting enough to eat, they may be less inclined to participate in the larger community)

3.1.3 Impact of Current and Anticipated Trends in Country/Traditional Food Harvesting

As a result of global processes, the northern environment has become more variable and less predictable than in the past. The evaluation found that environmental and climate changes have had a significant impact on traditional harvesting activities. As a result of these modifications, the existing food web is shifting; new species are migrating into traditional harvesting areas. These changes are linked to both negative and positive outcomes. In some instances, traditional food sources are being displaced, out-competed or preyed upon by new species moving in from the south (e.g., killer whales preying upon beluga whales). In other instances, new species mean new sources of food for northern people (e.g., moose).

Expert panel participants and key informants went on to note that exposure to new and emerging environmental contaminants is negatively impacting wildlife populations. As a result of these changes, Inuit have less confidence in traditional foods. For example, when Inuit notice animals acting oddly or when the taste and quality of the meat is different than before, they become fearful of eating it.

Climate change has led to an increase in the unpredictability of factors such as weather, ice and wildlife behaviour. This in turn, has created an atmosphere of anxiety and stress among hunters. There are an increasing number of accidents due to changes in weather patterns and ice composition (changes in ice flow). Climate change is having an influence on freeze-up and break-up patterns, which is affecting the movement of animals and thus the availability and accessibility of these traditional food sources. Increases in temperature have resulted in heat stress for northern animals and have disrupted breeding schedules, and resulted in the emergence of new wildlife diseases in the north as a consequence of disease vectors moving up from the south.

Traditional harvesting is also on the decline due to changing attitudes regarding country food. The evaluation found evidence of a decrease in traditional food intake by the younger generation and this has led to a change in the types of harvesting activities. The way in which people eat country food is beginning to change. It used to be that Inuit would eat almost the entire animal but now, there is a tendency for the younger generation to eat much less (i.e., they have different tastes). The high cost of hunting (noted above) and food have acted as a deterrent to traditional harvesting among Inuit and First Nations living in the north.

3.2 Design and Delivery

3.2.1 Program Objectives

The primary objectives of the Food Mail Program are to address issues of northern food security and nutrition by improving access to affordable healthy food and other essential items in remote communities where costs of food would otherwise be too expensive for most residents (INAC 2008b).

3.2.2 Program Outcomes

The outcomes of the Program, as indicated in INAC's 2006-07 Department Performance Report (INAC 2007b) include:

- Improved supply and increased consumption of nutritious food in isolated northern communities;

- Improved food security, nutrition and health for Northerners; and

- Strengthened individual and family well-being for First Nations, Inuit and Northerners in support of an improved quality of life.

3.2.3 Policy Framework for the FMP

The evaluation found no evidence of a comprehensive policy framework that addresses issues of food security and its relation to nutritional/health status for isolated communities in northern Canada. It is not clear that an integrated food security policy exists, of which the FMP is presumed to be a key instrument. In fact, the June 2008 audit of the FMP noted that there are a number of policy issues related to the program, including the fact that there is no explicit policy context for the program, a lack of clarity as to whether the program is a core federal responsibility and a question about whether the program would best be delivered by the federal or provincial, territorial and regional governments (INAC 2008c).

Expert panel participants noted that the lack of a comprehensive policy framework and an integrated food security policy compromises the ability of the FMP to effectively achieve its overarching program objectives and outcomes. The task of improving food security, nutrient intake, and the health and well being of isolated northern residents is complex and requires a multidisciplinary approach.

3.2.4 Communications

Multiple lines of evidence found that INAC's communication about the FMP to community members is lacking. There is little awareness of the program, about what foods are eligible for the program, and about the benefits associated with the subsidy. Most residents (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) are unaware that a subsidy is being passed on to them through the retail stores. Those accessing the FMP through direct/personal orders find out about the program by word of mouth from individuals currently placing orders in the south. It appears as though the onus is on individuals to find out about the program rather than INAC advertising its existence. There are also ineffective communications between the FMP and Aboriginal organizations at the national and regional level. This limits the ability of these organizations to help assist their respective community members.

Challenges also arise in sending clear messages to stakeholders outside the participating agencies (INAC, CPC and HC). The complexities of the program add difficulty in communicating with such agencies with respect to program operational requirements and the uniqueness of the beneficiaries.

For example, key informant and expert panel participants noted that many bureaucrats located in the south and southern Canadians in general have a limited understanding of the geographic limitations (e.g., remoteness, weather) associated with northern locales. There is also a tendency for stakeholders to be unaware of the multi-disciplinary nature of the program (i.e., food is linked to health, nutrition, culture, food security, transportation, and retail).

3.2.5 Roles and Responsibilities

The key FMP stakeholders – INAC, CPC, and HC – believe that their respective roles and responsibilities are well-communicated, understood and agreed upon by all. The FMP is managed by INAC, administered by CPC, and advice on the nutritional aspects of the program is provided by HC (although they have no decision making power).

INAC works very closely with CPC. The two parties meet monthly and enjoy open lines of communication. Although INAC does not meet regularly with HC, HC provides advice on such things as the list of foods eligible for the program, input on nutrition survey work, and advice on the development of the Northern Food Basket. CPC, on the other hand, noted that the role of HC is not clear to them because they have little direct contact. Other interview respondents stated that HC should play a greater role in the delivery and communication of the FMP. It has been suggested that HC should be more engaged and take more of a proactive role in the program. Specifically, interviewees noted that the FMP should be directly linked to all HC programs that have a nutritional component (e.g., Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program, Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative, Aboriginal Head Start, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Program, and Children's Oral Health Initiative). No specific examples of how HC and the FMP would work together on these programs were provided

Community-base airline representatives expressed some confusion about the roles and responsibilities assigned to each of the players involved the FMP delivery chain. There is some question about who handles each leg of the delivery process and the timelines associated with those deliveries.

3.2.6 Program Capacity

The evaluation found evidence that the FMP is challenged by resource constraints. The FMP suffers from a lack of program capacity: few staff and a limited budget. Respondents noted that more people are needed to enhance communication, research and analysis. Currently the program has four staff – the largest full-time complement in the program's history. Typically, INAC has assigned two staff members to manage a $45 million program. The funding challenges of the FMP consume a significant amount of program staff's time and energy. Increased funds for the program would make it possible for staff to engage to a greater degree in research, analysis, policy development and program monitoring at the community level.

Entry point interview participants noted that effective program delivery is dependent on the capacity of all players involved in the FMP, including CPC, airlines, and wholesalers. For instance, airlines must have the capacity to ensure fast and efficient delivery of goods, stores in the south must have the capacity to adequately pack the boxes and transport them to the airport, and CPC must have the staff need to inspect the eligible item packages in a timely fashion.

High rates of turnover among northern store managers compromise the capacity of northern retailers to successfully deliver the FMP. Community members believe that effective and efficient store management includes the removal of expired or spoiled FMP items, ordering requesting FMP items, and keeping the stores shelves as stocked as possible with quality products.

3.3 Accountability

3.3.1 Results-based Management and Accountability Framework

At the start of the evaluation of the FMP (August 2008) there was no comprehensive results-based management and accountability framework (RMAF) in place to help manage the administration of the FMP. In October 2008, a draft version of an RMAF was released for discussion; revisions to the framework have since been made. Program accountability has occurred through annual Departmental Performance Reporting (DPR).

3.3.2 Performance Measurement Framework

As of August 2008, when this evaluation commenced, no performance measurement framework (PMF) had been developed to help track the progress of the FMP. The draft 2008 RMAF contained a recently developed PMF.

3.3.3 Results-based Information

There is no formal monitoring and reporting requirement for the FMP in its entirety. The program is, however, required to report on certain aspect of the program to the Deputy Minister at specified times and to contribute to the reporting of results in the Departmental Performance Report (DPR).

Key informant interviews revealed that the FMP collects a great deal of data although until quite recently, this has never been done formally. With the release of the RMAF and the PMF, the FMP is now moving toward a more formalized reporting process. The program has now begun writing internal quarterly reports for INAC (includes information such as CPC payment amounts, food mail volumes). Additionally, the program reports on nutrition surveys and the highlights of regional/community price survey results (the findings of the price surveys are typically disseminated to participating communities). FMP personnel also collect information to help explain/measure increasing volume and costs, as well as the impact of the FMP on increasing costs. CPC carries out four end-to-end inspections each year to evaluate how well the FMP process of shipping the food is working. The end-to-end inspections involve INAC, CPC, shippers, airlines and retailers. The inspections do not, however, extend into the communities.

3.3.4 Overall Program Accountability

Community members aware of the FMP subsidy suggested the need for improved monitoring of the prices in the retail outlets to help ensure that FMP savings are being passed along to the consumers. Many feel that northern retailers are not passing along the full subsidy. Community members expressed concern regarding food safety issues and highlighted the stores' responsibility in ensuring that outdated and spoiled products are not sold to community residents. The retailer should be responsible for protecting community members from potential food borne illness caused by spoiled food.

Many retailers and community members accessing the FMP through direct orders complained about damaged or spoiled goods. While many direct order recipients noted their ability to receive a refund or exchange for any damaged items, retailers are not as lucky. Many retailers are responsible for absorbing 100% of the costs associated with damaged or spoiled products since most times the product is thrown away. Some retailers feel that CPC should assume some responsibility for losses incurred during the shipping of FMP eligible items. Other retailers believe that airlines should accept responsibility for the delivery of goods, including lost or missing manifests, delays in delivery due to mechanical difficulties, damaged items, and lack of notification about shipment arrivals.

Southern wholesalers should be responsible for ensuring that the products they ship to the north are of high quality. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that southern wholesalers may be shipping products that are close to their expiry/best before date to the north because they cannot sell them in their southern stores. During field visits, in fact, evaluators found that there are no longer expiry dates on bread in some communities because, as retailers conceded, the bread would have to be taken off the shelves.

3.4 Effectiveness

3.4.1 Program Reach

The FMP is intended to target all residents in eligible northern communities regardless of income level. There is some question about whether the FMP is reaching those with the most need (e.g., Aboriginal people on social assistance) or those with the most money (e.g., RCMP, nurses and teachers). While direct order purchases are less expensive (because they do not include retail mark-up), those most in need of affordable food items are unable to access this FMP option because they often times lack a credit card (required for payment) and/or the communication format required to carry out the ordering (phone, fax or email). Consequently, the majority of direct orders are placed by southerners, with high incomes, residing in the north. There are some instances, however, in which individuals with credit cards, or Band Councils, place orders on behalf of those without a card. An alternative to the credit cards (e.g., cash link (debit) system used in Winnipeg) could improve residents' capacity to access affordable food items through direct orders.

There is a positive association between median individual income and food mail volumes such that for every additional $1000 of individual income in a community, per capita shipment volumes go up approximately 10 kg.. Additionally, for each one percent of non-Aboriginal population composition in a community, the per capita food mail volume of shipments increases by 5-8 kg.. These findings suggest that food mail volume is correlated with income level, and that non-Aboriginal people may be consuming considerably more perishable foods (kg. per person) than their Aboriginal counterparts, based on FMP shipment volumes and making allowance for food consumption by visitors and non-community residents in surrounding areas.

3.4.2 Food Affordability

The evaluation found that the FMP is achieving greater degrees of food affordability relative to what would be the case in the absence of the program. There are, however, food price differences between regions and communities as result of variations in electricity costs, the costs of surface transportation to the entry points, local handling costs at the destination point, and retail competition. While perishable food costs are approximately twice as high in northern communities as in southern Canada, costs would be much higher without the program.

Pilot projects undertaken in Fort Severn, Kangiqsujuak and Kugaaruk found that the two of the five main reasons that people in the north do not buy nutritious, perishable food is because it costs too much money and they cannot afford it. The pilot projects which were carried out to asses the impacts of further reductions in the rate charged for shipping key "priority perishable" foods (vegetables, fruit, most dairy products, frozen juice and eggs), led to improvements in the quality, variety and availability of healthy foods in all three pilot communities and a reduction in the hunger in two of them. The increased subsidy also resulted in significantly higher per capita volume shipments (and presumably of consumption) of perishables. Thus supporting the notion, that further decreases in food costs lead to increases in the purchase of nutritious foods in the north.

While food prices are lower as a result of the FMP subsidy, food is still not affordable, even at reduced rates, for many northerners. Those individuals depending on social assistance do not have enough money to meet their basic food needs given payment amounts do not match cost of living increases nor do they take into consideration fluctuations in food prices (as a result of access – summer roads versus fly in during the winter). The FMP subsidy does not address the adequacy of northern household incomes in relation to housing and living costs (including the overall cost of food). While the FMP makes a difference in terms of food affordability and attempts to influence food security, programs aimed at northern household income levels and shelter costs are likely to play a larger role in terms of food security than does the FMP. Those aware of the subsidy expressed concern about the degree to which the FMP subsidy is being passed on to communities.

Nutritious food choices are made easier when healthy foods (e.g., 100% orange juice) are less expensive that unhealthy items (e.g., pop). Health professionals and researchers agree that nutritional foods should cost less than unhealthy food options that have a negative affect on the overall health and nutrition of community members. Community members and retailers suggested that essential or staples items such as bread, milk and fruit juices should include additional subsidies so as to make these products more affordable to the northern population. The high price of eligible foods is a deterrent to northerners on a fixed budget experimenting with new food items. Community members are unwilling to risk spending their money on food items that their families may not enjoy; they would prefer to remain with foods they know will be readily accepted.

Direct ordering of FMP items is the most cost effective way to access eligible items. Community members estimate savings of at least 25% when comparing direct orders with retail orders. This difference in price reflects the elimination of many of the middlemen and the retailer overhead (e.g., costs of transportation from the drop off point to the store, the costs of electricity and heat, building and maintenance costs, and staff salaries), which are traditionally included in the price of all retail items. Although significant savings are associated with direct ordering, some community members and program/institutional representatives prefer to shop in the retail stores as a show of community support.

3.4.3 Food Quality, Selection and Cultural Appropriateness

The quality of eligible food items was identified as a challenge to the FMP. Food mail items are often past their expiry date, spoiled or damaged due to mechanical difficulties, inclement weather, and/or poor packaging/handling. Fruits and vegetables have a tendency to freeze during the winter months and rot during the summer months if left on the tarmac or un-refrigerated for a period of time. Community members, as well as entry point respondents and key informant interview participants expressed the belief that items that are nearing their expiry date or best before date are shipped to the north because they cannot be sold in the south (i.e., southern shoppers have the prerogative to be more discerning about their shopping purchases). During site visits, evaluators observed spoilage first hand in different locations and heard such concerns from some store managers and people purchasing direct orders.

The need for greater quantities of perishable items was noted. When the items arrive in the community, there is a rush to purchase them quickly, leaving the shelves bare. This is a particular problem in communities that only receive food shipments once a week. Community members and retailers spoke about going without essential items such as bread for weeks due to winter weather.

Direct order recipients indicated that food costs, quality and selection are typically much better when ordering directly from the south than purchasing from community retailers.

Expert panel participants suggested disconnect between Ottawa and the north with respect to food choices. The belief is that the south is imposing food ideas on the north. For example, should items like lettuce, kiwis and star fruit be shipped up north when that money can be spent subsidizing more culturally appropriate food items? Aboriginal people tend to buy items that have a long shelf life, require little preparation and are high in calories. It was suggested that the program revise the eligibility list to more accurately represent the food preferences of northerners, with the aid of Aboriginal organizations. A rationale for the inclusion/exclusion of items is required. Other individuals believe that the eligibility list should be expanded to include all food items available at the store since some find the process to be patronizing to northerners (e.g., not educated enough to determine what foods to eat).

3.4.4 Diet and Nutrition

The evaluation found that northern diets have changed over time, with a reduction in country food consumption and a generally high consumption of unhealthy high-sugar or high-fat foods of little nutritious value. Nutrition surveys conducted by INAC from 1992-2004 revealed the following:

- Macronutrients: In terms of mean daily caloric composition of macronutrients, there are general trends of an increased consumption of carbohydrates and a decreased consumption of protein.

- Micronutrients: Low consumption of organ meat, country fat and fruit and vegetables and dairy products was responsible for the low intake of certain micronutrients: principally folate, calcium, and vitamins A, C, B6. This was of particular health-concern for pregnant and lactating women.

- FMP-Eligible Food Groups: In terms of mean daily caloric composition by FMP-eligible food groups, there are general trends of an increased consumption of 'nutritious perishable foods', a decreased consumption of non-perishables foods and 'country foods' and an increased consumption of 'other foods' (i.e. generally high in fat or sugar content and not judged to be 'nutritious).

- Food Type: In terms of mean daily caloric composition by food type, there has been very little change in dairy and egg consumption, and some trend of increases fruit and vegetable consumption in certain communities. Generally, the majority of fruit consumption is in the form of fruit juice. There is a general trend of increased consumption of store-bought meats (and meat-alternatives) which compensates for the reduced consumption of country food meat.

Community case study visits revealed high levels of variability in the northern diet with some individuals/families heavily dependent on country food while others are almost entirely dependent on store-bought foods. Food choice is influenced by factors such as age, income level, availability of country foods, food quality, and personal preference.

Retailers noted that chips, pop and cigarettes are their most frequently purchased items. There is also a high demand for processed, prepared foods such as sandwiches and frozen dinners. Pilot project survey results from the three communities revealed that, the most frequently consumed food items were – in order – pop, coffee, tea, Tang, white bread, chocolate bars, Kool-Aid and potato chips. Findings from the Inuit health survey revealed that while carbonated beverage consumption is not inexpensive, it is widespread. In one community, as much as a litre a day of pop is consumed by youth – suggesting that price alone is not responsible for determining food purchasing behaviours. This study also found that when traditional food was consumed, youth drank nearly one can less of pop a day compared to those for whom no traditional food was consumed. It has been surmised that poorly nourished individuals crave the caffeine and sugar high because their diets are not meeting their nutrient needs.

Increased communication about the FMP and education and general awareness building activities on healthy eating may lead community members to realize the merits of purchasing healthy foods.

Many children in northern communities are benefiting from improved nutrition in day care centres and through school breakfast and snack programs – all of which are taking advantage of the FMP subsidy either through retail or direct order purchasing.

Community day care centres are attempting to address poor nutritional intake by creating weekly menus based on Health Canada food groups. Some communities have integrated country food into the menu such that they pay a local hunter to bring them fresh meat and fish. This was done initially to address a high level of anemia in the children. For many children, this is the only place that they consume healthy foods, once they return home for the day they consume a diet low in nutritional value (high in fat and sugars).

Breakfast programs are believed to be providing children with healthy foods to which they may not otherwise have access. As a consequence of running a breakfast program, one community has noticed a decrease in the number of children fighting and in the ability of children to concentrate while in class. In one community, the breakfast and snack programs teach children about healthy food options. In turn, they share these lessons with their parents who request that the items be available for purchase at the retail stores. Parents are willing to purchase healthy snacks for their children if those snacks are reasonably priced.

A lack of knowledge about healthy eating has an impact of dietary decisions. Many Inuit have quite recently transitioned from a subsistence way of life to participation in the wage economy consequently education has a big impact in improving nutrition rather than simply access to nutritious foods.

There are many factors (e.g., level of education, understanding of dietary-nutrition-health relationships, cultural preferences, level of income, retail food marketing and pricing strategies) which, along with the FMP subsidy for eligible foods, influence northern consumer food choices.

3.4.5 Health Indicators

Self-reported health status among Inuit and First Nations respondents in one region (Quebec-Nunavik) and the five communities that underwent nutritional surveys (i.e., Kangiqsujuak,, Pond Inlet, Repulse Bay, Kugaaruk and Fort Severn) were much poorer than that of the general Canadian population. The percentage of respondents reporting either 'fair' or 'poor' health was 25-63% for surveys from the early 2000s, compared to 21-22% for surveys from the late 1990s. There was a wide variation by case, from a low of 21-22% (Pond Inlet, Repulse Bay) to a high of 63% (Kangiqsujuaq [Note 3]). These rates of self-reported poor health compare to 6-10% for Canada/Quebec rates for comparable age/sex groups.

In terms of high Body Mass Index (BMI) indicative of obesity, the cases averaged about 35% of respondents being obese, with a high of 48% (Repulse Bay) and a low of 23% (Kangiqsuujuaq) [Note 4]. For three communities (Repulse Bay, Pond Inlet, Fort Severn) the rate of obesity was increasing (no change was available for the other three communities) [Note 5].

In terms of level of activity, only about a third of respondents were physically active (definitions varied across studies). The community with the highest level of activity (Kugaaruk, 45%) was noticeable as the community with the lowest rate of self-reported fair/poor health (25%). Generally, there was reduced activity in terms of time spent 'on the land' engaged in traditional hunter/gatherer activity.

3.5 Cost Effectiveness

Although postage rates have not increased since 1993, FMP expenditures have steadily increased since 1999/00 (refer to Figure 1). The estimated cost to INAC to administer the FMP in 2007/08 was approximately $45 million. Expenditure forecasting completed by CPC estimates costs at approximately $58 million and $65 million in fiscal years 2008/09 and 2009/20, respectively. While program costs continue to increase, the funding reference level (NSM-Base) has remained unchanged since 2002/03 (at $27.6 million annually) leading to a considerable yearly shortfall.

Figure 1: Food Mail Program Expenditure (Actual and Forecasted)

Source: Expenditure from INAC website: Churchill Entry Point Review; INAC website for 2004-2007: Food Mail Info Sheet; Forecasts (by CPC) for 2008 and 2009 [Notes: Years are Fiscal Year .e.g. 2007 is for 2007-08]

The table above assesses the expenditures in $millions for the Food Mail Program from the year 1986 to 2009. The graph includes three lines: the first is a full black line which portrays the fluctuations in program expenditures throughout the years; the second is a broken line which demonstrates the fluctuations in the amount of base funding provided to the program within the same time period, and lastly, the third is a dotted line which represents the difference between total expenditures and total program funding (or shortfall).

According to the graphic provided, the program's expenditures declined from $19 million to around $12 million during the period between 1987 and mid-1993. Expenditures rose by almost $5 million from mid 1992 to 1996, but eventually decreased to a total of $14 million by early 1997. From 1997 to 2006, expenditures increased to a total amount of $40 million. From 2006 to 2007, there was a slight decrease by $1 million; however program expenses eventually rose to a total of $ 66 million by early 2009.

From 1987 to early 1992, the amount of base funding remained the same as the total of expenditures, meaning that both variables simultaneously experienced a decline from $19 million to $ 12 million. Between 1993 and 2002, there were slight fluctuations which led the amount of base funding to increase to a total of $16 million. There was a sharp increase in 2001 by approximately $11 million. Finally, from early 2003 to 2009, base funding remained constant at a total of $28 million.

The evaluation found that the costs and revenues associated with the FMP over the period 1998/99 to 2008/09, based on Canada Post (2008) data, are as follows:

- INAC total funding or subsidy (food mail costs minus postage revenue) for the FMP increased by 283% between 1998-99 ($15.2M) and 2008-09 ($58.3M-estimate)

- INAC funding per kilo of shipment increased by 63% (6.4% per year)

- Food mail weight in kilos rose by 134% (13.4% per year)

- Total food mail costs per kilo have increased by 4.3% per year