Archived - Evaluation of Community-Based Healing Initiatives Supported Through the Aboriginal Healing Foundation

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: December 7, 2009

PDF Version (1.63 MB, 72 pages)

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response / Action Plan

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Evaluation Methodology

- 3.0 Evaluation Findings

- 4.0 Cost Effectiveness

- 5.0 Future Directions

- 6.0 Conclusions

- 7.0 Recommendations

- Literature & Documents Consulted

- Appendix A

Acronyms

| AFN | Assembly of First Nations |

|---|---|

| AHF | Aboriginal Healing Foundation |

| CEP | Common Experience Payment |

| DOJ | Department of Justice |

| GOC | Government of Canada |

| FNITP | First Nations and Inuit Transfer Payments (Information System) |

| HC | Health Canada |

| IAP | Independent Assessment Process |

| INAC | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada |

| IRS | Indian Residential Schools |

| ITK | Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami |

| IRSRC | Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada |

| MNC | Métis National Council |

| PALO | Department of Public Affairs, Liaison and Outreach |

| PSEPC | Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada |

| RBAF | Results-based Audit Framework |

| RMAF | Results-based Management and Accountability Framework |

| SA | Settlement Agreement |

| SAISC | Settlement Agreement Implementation Steering Committee |

| SOW | Statement of Work |

| TOR | Terms of Reference |

| TRC | Truth and Reconciliation Commission |

Executive Summary

Introduction

The following report presents the findings of an evaluation undertaken by DPRA Canada in association with T.K Gussman Associates, on behalf of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, of the community-based initiatives of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) for the period April 2007 to May 2009.

The AHF, begun in 1998 in response to recommendations arising from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the Government's subsequent Action Plan, "Gathering Strength", has had the principal objective of healing Aboriginal individuals, families and communities of the effects of abuses and cultural losses suffered as a result of attendance at Indian Residential Schools (IRS). Over the ten year period, the Government of Canada (GOC) has contributed $515 million to the AHF to support this objective. The last contribution was in the form of an additional $125 million in funding that arose from the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) and covers the period from 2007-2009.

The model followed by the AHF has been to fund community-driven and culturally-based projects that use a variety of healing methods and models, in response to community needs. The evaluation is part of the terms of the IRSSA and the Funding Agreement between the AHF and the GOC, which outlines the Minister's right to conduct a program evaluation.

The primary objective of the evaluation has been to assess the effectiveness, impacts, cost-effectiveness and continued relevance of the healing initiatives and programs undertaken by the AHF under the Settlement Agreement for the period under review, and provide evidence that will support the Government's decision-making regarding whether and to what extent funding should continue beyond the current end date of March 2010 for some projects and March 2012 for others (the 11 healing centres currently funded).Methodology

The evaluation took place over a very condensed time period between June and September of 2009. The methodology pursued a number of lines of evidence, as follows:

- Review of 108 documents and literature sources;

- Review of Administrative files (Annual and quarterly reports for 07/08 and 08/09 for a sample of 29 AHF-funded projects (including the eight case study projects);

- 35 Key informant interviews of individuals from the following groups: AHF; relevant government departments; Aboriginal organizations; project directors from AHF-funded projects outside the case study sample; and subject experts from across Canada; and

- Eight Community case studies conducted on-site at locations across Canada. During the case studies, a total of 145 interviews were conducted with participants and key stakeholders.

Highlights of Evaluation Findings

Program Effectiveness:

There is almost unanimous agreement among those canvassed that the AHF has been very successful at both achieving its objectives and in governance and fiscal management.

A number of indicator measures provide evidence that AHF healing programs at the community level are effective in facilitating healing at the individual level, and are beginning to show healing at the family and community level. AHF research has shown that it takes approximately ten years of continuous healing efforts before a community is securely established in healing from IRS trauma.

Program enrolment is growing at an average of 40 percent in the projects reviewed, and case study sites report growing enrolments and increased demand for healing services. Project data show that enrolments include increasing ratios of historically hard-to-reach groups such as youth and men.

Although evidence points to increasing momentum in individual and community healing, it also shows that in relation to the existing and growing need, the healing "has just begun". For Inuit projects in particular, the healing process has been delayed due to the later start of AHF projects for Inuit.

The majority of projects note they are not sustainable without AHF funding, although efforts are being made in some cases to secure funding from other sources; however, as there are no other agencies with a matching mandate, funding partners are difficult to find.

Program Impacts:

Impacts of the programs are reported as positive by the vast majority of respondents, with individual impacts ranging from improved family relationships, increased self-esteem and pride; achievement of higher education and employment; to prevention of suicides. Reported community impacts are growth in social capital indicators such as volunteerism, informal caring networks, and cultural events. One of the notable impacts reported by case study communities is that the "silence" and shame surrounding IRS abuses are being broken, creating the climate for ongoing healing. Projects report that capacity for healing has been built in communities and between communities; an example of such inter-community capacity growth is the sharing of best practices that has occurred between communities in both formal and informal ways, supported by the AHF and undertaken by projects on their own.

Impacts of the GOC Apology and Settlement Agreement:

Although reaction to the GOC Apology was mixed, the evaluation found that the majority of respondents felt it played a major role in creating awareness of IRS issues in the general public, and for many former IRS students and their families, provided the acknowledgement and validation of their suffering they had been looking for.

The Common Experience Payment and Independent Assessment Process are increasing the need for healing by "opening up" the issue for many Survivors for the first time. AHF projects and Survivor Societies are seeing a significant increase in demand for services in relation to these processes.

Continued Relevance of AHF Healing Programs:

Project reports show that healing program reporters identify an array of negative social indicators and challenges to healing that persist in their communities. Evaluation evidence from case studies shows that almost 90 percent of respondents estimate that "more than 50 percent" of their community members need healing from the effects of IRS. The estimated high level of need, together with the growing program enrolments and the anticipation that the Settlement Agreement processes will continue for at least another three years, support the argument for the continued relevance of AHF healing programs. The evaluation results strongly support the case for continued need for these programs, due to the complex needs and longterm nature of the healing process.

Given the Settlement Agreement commitment by the GOC, and keeping in mind the assessments of the number of Survivors and intergenerationally impacted who are anticipated to need support; and the fact that Health Canada support programs are designed to provide specific services that are complementary but different to those of the AHF; and the reported numbers of Survivors seeking help from AHF and Survivor Societies, the logical course of action for the future would seem to be continuation of support for the AHF. This support is needed at least until the Settlement Agreement compensation processes and commemorative initiatives are completed, and ideally, beyond, until indicators of community healing are much more firmly established and Aboriginal people and communities either no longer need such supports, or are able to achieve healing from IRS effects through other means. Expert key interviewees note that there is presently no equivalent alternative that could achieve the desired outcomes with the rate of success the AHF has achieved.

Recommendations

It is recommended that:

1. The Government of Canada should consider continued support for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, at least until the Settlement Agreement compensation processes and commemorative initiatives are completed.

2. The Government of Canada explore options with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation to determine how best to maximize any additional resources, should they become available, in order to be better able to meet the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians.

3. The Government of Canada undertake a study, in partnership with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, research organizations, and stakeholders, to determine the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians post Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and determine whether funding should be continued and, if so, to what extent, and what role, if any, the Government of Canada should play.

4. The Government of Canada implements, in the funding agreement with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, a requirement to collect data to help determine cost effectiveness of community-based healing projects supported by the Foundation. They should also examine the possibility of a mandate to conduct strategic research and evaluation activities; however, this enhanced mandate should not detract from funding that would normally flow to community-based projects.

Management Response & Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of Community-Based Healing Initiatives Supported through the Aboriginal Healing Foundation

Project Number: 1570-7/08042

Region or Sector: Resolution and Individual Affairs

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager | Planned Implementation and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Government of Canada should consider continued support for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, at least until the Settlement Agreement compensation processes and commemorative initiatives are completed. | INAC will explore the feasibility of developing a policy proposal to support the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, taking into account the needs of survivors, their families and their communities. | Director General, Policy, Partnerships and Communications Branch | March 31, 2010 |

| 2. The Government of Canada explore options with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation to determine how best to maximize any additional resources, should they become available, in order to be better able to meet the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians. | INAC will explore, in consultation with Health Canada and the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, how best to maximize the benefits/healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians should additional resources become available. | Director General, Policy, Partnerships and Communications Branch | March 31, 2010 |

| 3. The Government of Canada undertake a study, in partnership with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, research organizations, and stakeholders, to determine the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians post Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and determine whether funding should be continued and, if so, to what extent, and what role, if any, the Government of Canada should play; and | INAC commits to undertake a study, in partnership with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, research organizations and stakeholders, to assess the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians. INAC will raise this issue with existing fora to determine what role Canada could play in the healing needs of Aboriginal Canadians. | Director General, Policy, Partnerships and Communications Branch | March 31, 2012 |

| 4. The Government of Canada implement, in the funding agreement with the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, a requirement to collect data to help determine cost effectiveness of community-based healing projects supported by the Foundation. They should also examine the possibility of a mandate to conduct strategic research and evaluation activities; however, this enhanced mandate should not detract from funding that would normally flow to community-based projects. | INAC will include a requirement to collect data to help determine cost effectiveness of community-based healing projects supported by the AHF. Should resources become available, INAC will explore the possibility of expanding the mandate of the Aboriginal healing Foundation to develop and implement a strategic research and evaluation plan. |

Director General, Policy, Partnerships and Communications Branch | March 31, 2010 |

1.0 Introduction

Indian Residential Schools (IRS) officially operated in Canada from 1892 to 1996, either entirely government-administered, or through funding arrangements between the Government of Canada (GOC) and the major Christian churches of the period. Thousands of Aboriginal people who attended these schools have reported that physical, emotional, and sexual abuses were widespread in the school system. [Note 1] The equally powerful cause of trauma reported by former students, their families, and their descendants is the loss of culture and language, and the lifelong effects on people who, as children, were institutionalized in settings alien to them, away from their families and social networks.

The legacy of this trauma has reverberated through Aboriginal communities until the present. By one estimate, there are approximately 86,000 of these Survivors still living in Canada. [Note 2] The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended that Canada take action to address these impacts on individuals, families and communities, and the GOC's "Gathering Strength – Canada's Aboriginal Action Plan" [Note 3], recommends "a healing strategy to address the healing needs of Aboriginal People affected by the Legacy of IRS, including the intergenerational impacts" [Note 4]

1.1 Program Description

The federal government provided a $350 million grant in 1998 for community-based healing of residential school trauma, and on March 31, 1998, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation (AHF) was created, with a ten year mandate. Before the end of the initial ten year funding period, the federal government subsequently provided an additional $40 million for 2005-2007. Since 1998, the GOC has contributed $515 million to the AHF to support the objective of addressing the healing needs of Aboriginal People affected by Residential Schools.

As part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) reached through a judicial process involving a number of parties, the GOC provided an additional $125 million endowment, [Note 5], to apply to the AHF for the period from April 1, 2007, to March 31, 2012. The AHF applied this $125 million to existing AHF projects. The $125 million has extended funding for existing projects for three years (ending March 31, 2010) and for eleven healing centers for four and a half years (ending March 31, 2012). The funding allocation and the time frame between April 1, 2007, and May 2009 are the focus of this evaluation.

The Foundation, which is an Aboriginal-operated, not-for-profit corporation, operates independently of government, and has administered the fund in accordance with a Funding Agreement between the Foundation and the GOC. The intention from the outset has been that the AHF not duplicate existing services provided "by or within funding from federal, provincial or territorial governments." [Note 6]

The AHF governance structure includes a Board of Directors whose responsibilities include final approval for the funding of healing projects, and an Executive Director that oversees the day to day management of the foundation. The AHF has been noted for excellence in governance and management. [Note 7]

The long term goal of the AHF has been to break the cycle of physical and sexual abuse that is a consequence of the legacy, and to create sustainable well-being for individuals and communities. The objective of the AHF is to address "the healing needs of Aboriginal People affected by the Legacy of Indian Residential Schools, including the intergenerational impacts, by supporting holistic and community-based healing to address needs of individuals, families and communities, including Communities of Interest". [Note 8] The activities and outputs of the AHF have included conferences and gatherings, training, research, the production of historical materials, and the promotion of awareness and understanding of the needs and issues surrounding residential school trauma and its legacy.

Community-based projects funded by the AHF were designed in and by communities to address the healing needs as understood by community members at the time; as a result, there is a range of healing approaches and modes used, within eight broad categories of eligible projects established by the AHF: (the last two of the list applied in the start-up phase):

- Those providing direct healing services;

- Those focused primarily on prevention of the effects of abuse, and awareness of the Legacy;

- Those that conduct Gatherings and conferences;

- Those that honour history by a variety of means, including memorials;

- Those focused primarily on training for potential healers and building capacity for the healing process;

- Those focused on knowledge-building, including through research and capacity building;

- Those focused on assessing the healing needs of the community (needs assessment); and

- Those that address project design and set-up.

The AHF model has emphasized a wholistic, community-based approach that emphasizes training and capacity building in healing; and reliance not only on "professional" healers, but healers with lived experience and cultural knowledge. One of the conclusions reached by AHF after several years of research, is that "culture is good medicine". [Note 9]

Projects are monitored by the AHF on the extent of their achievement of the following measures, intended to support the achievement of the overall program objective:

- Promotion of linkages to other government health and social services programs;

- Focus on early detection and prevention of the intergenerational impacts of physical and sexual abuse;

- Recognition of special needs, including those of the elderly, youth and women; and

- Promotion of capacity-building for communities to address their long-term healing needs. [Note 10]

Demand for AHF-funded projects in Aboriginal communities has been high; the AHF has received over $1.3 billion in funding requests since its inception, far outstripping the $515 million funding allocation. In 2001, there were 310 AHF-funded community projects, serving over 1,500 individual communities and approximately 60,000 individual participants. [Note 11] Currently, there are just over 140 contribution agreements for AHF projects distributed across the provinces and territories. Those projects that were funded under the 2007 endowment (i.e. 2007-2010 or 2012) are projects that have demonstrated ongoing success.

Table 1: Current Contribution Agreements by Region

| Region | Number of Contribution Agreements |

|---|---|

| Northwest Territories | 5 |

| Alberta | 10 |

| British Columbia | 19 |

| Manitoba | 27 |

| Labrador | 2 |

| Quebec | 19 |

| Nunavut | 12 |

| Yukon Territory | 4 |

| Ontario | 20 |

| Saskatchewan | 18 |

| New Brunswick | 2 |

| Nova Scotia | 2 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 |

The final report of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation [Note 12] outlines the distribution of the Healing Fund by group, as follows: All groups (29%); Inuit (5%); Métis (5%); and First Nations (59%). In terms of distribution of projects by type, the majority have consistently been "direct healing" (e.g. therapy, counselling, on-the-land cultural-based activities), and the percentage of such programs has increased over time (59% in 2004; [Note 13] 65% in 2008 [Note 14]

2.0 Evaluation Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Scope and Timing

The evaluation covers the period from the implementation of the fund in April 2007 until May 2009, and the scope covers AHF community-based healing initiatives. Additionally, the evaluation addressed the question of the effectiveness of a foundation as a policy instrument to address Aboriginal healing needs; this was done primarily through a literature review and canvassing of expert opinion.

2.2 Objectives of the Evaluation

The overarching intent of the evaluation was to fulfill the requirement of Article 8.01(2) of the IRSS, which states that "Canada will conduct an evaluation of the healing initiatives and programmes undertaken by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation to determine the efficacy of such [healing] initiatives and programmes and recommend whether and to what extent funding should continue beyond the five year period". [Note 15]

As noted above, the primary objective of the evaluation has been to assess the efficacy of the healing initiatives and programs undertaken by the AHF under the Settlement Agreement for the period under review, and provide evidence that will support the government's decision-making regarding whether and to what extent funding should continue beyond the current end date of March 2010 for some projects and March 2012 for others (the 11 healing centres currently funded).

2.3 Evaluation Issues

The evaluation that was undertaken focused on the following broad issues:

- Whether and to what extent the expected outcomes were achieved;

- The impacts of the program (intended and unintended) on the healing needs of the target populations;

- To what extent the AHF is the best course for supporting healing initiatives;

- What possible alternatives there may be to the current program;

- The degree of cost-effectiveness of the projects;

- The implications of the terms and implementation of the funds on AHF project activity; and

- The need for such programs and government support for them (relevance).

The evaluation was guided by the following overarching themes and questions:

- Effectiveness and Success

- To what extent are Community-based healing initiatives meeting the needs of Aboriginal people affected by IRS?

- To what extent are Community-based healing initiatives meeting the needs of Aboriginal people affected by IRS?

- Impacts

- What have been the impacts (intended and unintended) of the healing programs?

- What have been the impacts (intended and unintended) of the healing programs?

- Relevance

- Is there a continued need for the programs and are they relevant to the needs?

- Is there a continued need for the programs and are they relevant to the needs?

- Cost-Effectiveness

- How does the cost of delivering AHF community-based healing programs compare to appropriate alternatives?

- How does the cost of delivering AHF community-based healing programs compare to appropriate alternatives?

- Other Evaluation Issues

- What options, alternatives, or changes could feasibly achieve the desired outcomes of AHF-funded programs?

- What options, alternatives, or changes could feasibly achieve the desired outcomes of AHF-funded programs?

2.4 Data Sources

Information used to inform the evaluation was gathered from multiple lines of evidence:

- Preliminary consultations with six subject experts;

- Review of 108 documents and literature sources;

- Review of Administrative files (Annual and quarterly reports for 07/08 and 08/09 for a sample of 29 AHF-funded projects (including the eight case study projects);

- 35 Key informant interviews of individuals from the following groups: AHF; relevant government departments; Aboriginal organizations; project directors from AHF-funded projects outside the case study sample; and subject experts from across Canada; and

- Eight Community case studies. (see Appendices for more detailed summaries of each)

- Case studies included a total of 145 interviews/group interviews with staff and other key stakeholders (n=72) and participants (n=73) at the following project sites:

- "Circle of Strength Youth Mental Health Healing Project" Keeseekoose First Nation, Yorkton, Saskatchewan (SK),

- "Healing Together Using Our Traditional Values and Ceremonies" Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services, Kuujjuaq, Labrador,

- "Holistic Healing for Victims/Survivors of Shubenacadie School and their Descendants" Aboriginal Survivors for Healing, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island (PEI),

- "Kisohkastwanaw – We are Resilient" Buffalo Lake Métis Settlement, Alberta (AB),

- "Mamisarqvik: A Healing Place" Tungasuvvingat Inuit, Ottawa, Ontario (ON),

- "The ‘Next Step' Process, Integrated Holistic Approach to Wellness and Changing the Legacy of Residential Schools", Eyaa-Keen Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba (MB),

- First Nations House of Healing, "Tsa-Kwa-Luten Lodge" Inter Tribal Health Authority, Nanaimo, British Columbia (BC), and

- Yellowknives Dene First Nation Healing Project, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories (NWT).

- "Circle of Strength Youth Mental Health Healing Project" Keeseekoose First Nation, Yorkton, Saskatchewan (SK),

Interviews were conducted with program participants and key informants at case study sites as illustrated in Table 2, below. Case study key informants included project staff; frontline staff from other related community programs; traditional healers; and politicians.

Table 2: Case Study Interviews

| Case Study | Key Informants | Participant Surveys |

|---|---|---|

| "Healing Together", Kuujjuaq/Nunavik, Quebec | 7 | 7 |

| Tsa-Kwa-Luten Lodge, Inter-Tribal Health Authority, Nanaimo, BC | 30 | 11 |

| Mamisarqvik Healing Centre, Tungasuvvingat Inuit, Ottawa, ON | 10 | 5 |

| Yellowknives Dene First Nation Healing Project, Yellowknife, NWT | 6 | 5 |

| "Our Healing Journey", Buffalo Lake, AB | 11 | 6 |

| "Holistic Healing for Victims", Charlottetown, PEI | 9 | 9 |

| The "Next Step" Process, Eyaa-Keen Centre, Winnipeg, MB | 10 | 18 |

| "Circle of Strength", Keeseekoose, SK | 7 | 9 |

Case study sites were chosen according to a list of criteria to ensure that the sample represented all geographic regions; a range of urban, rural and semi-remote settings; all Aboriginal groups; and a range of project types, including healing centres.

The evaluation team consulted with an Advisory Group of AHF, government and independent experts who reviewed a Detailed Methodology Report and all data collection tools, as well as preliminary evaluation findings.

The evaluation methodology was adapted for this project to ensure cultural appropriateness of methods and the safety and wellbeing of participants. There were three primary ways of doing this: one was to provide for translation where needed to enable interviewees to participate in their Aboriginal language if desired; another was to design participant (i.e. Survivors and other project attendees) surveys so as to avoid causing any emotional harm; and finally, with the guidance and help of Health Canada, to arrange for Health Resolution Support Workers to be available for support to participants during and after they participated in the survey.

Case studies normally took place over a two-three day period, on-site at the project facilities [Note 16]

Of the program participants asked (n=66), 94 percent had either attended residential school or had a family member who attended. The age range of participants interviewed (n=72) is shown in the chart below.

Figure 1: Age Range of Participants (Case Study Surveys)

Figure 1: This figure shows a pie chart and legend, which groups the case study participants by age. There are four different age groups, each represented by a colour, and the chart shows the percentage representation for each group. It shows that 4% of participants were below the age of 25, 40% were between the ages of 25 and 45, 45% were between the ages of 45 and 60, and 11% were over the age of 60.

The gender breakdown of program participants interviewed for the evaluation was 63 percent female and 37 percent male.

2.5 Evaluation Limitations

Assessing Healing:

In strict terms, attribution of healing outcomes to specific program interventions is not possible in part, because of the following:

There here is no clearly defined or widely accepted agreement on what it means to be "healed" from the trauma of the residential school experience. Over the ten years of its mandate, the AHF has continually refined the list of indicators of healing that have been noted by project leaders and participants as meaningful to them; [Note 17] additionally, they have commissioned academic research on the meaning of healing with respect to the trauma of residential school. In the wider literature on this topic, the most recent scholarship is increasingly broadening the topic in two major ways: the roots of trauma are acknowledged to come from the entire colonization experience; [Note 18] and that these are enmeshed with the IRS experience; and trauma is acknowledged as going far beyond the individual, broadening the concept of healing beyond individuals to families, social networks and communities as a whole.

Healing is a long-term, complex, and non-linear process that is difficult to evaluate at any one period in time. [Note 19] Accordingly, the conclusions of the evaluation come from many lines of evidence in addition to the primary research undertaken: selected documents representing the ten years of evaluation and research undertaken by the AHF, including the three-volume Final Report; other relevant literature on Aboriginal trauma and healing and evaluation of these; and AHF reports from a sample of projects for the years 2007-2009.

It is recognized that wider social indicators (e.g. crime rates, poverty, suicide rates, education levels, physical health) have a direct impact on an individual's ability to achieve and maintain healing, but no accurate recent data are available on such indicators for Aboriginal communities. Without such a baseline, it is not possible to chart the extent to which communities may or may not be "healing" in these areas. The evidence for such indicators presented in this evaluation is based principally on the knowledge and experience of interviewees.

- The evaluation took place over a short time period and during the summer months, when it is difficult to contact interviewees.

- Over the time period under review, the client population changed. While some participants enrolled in programs more than once, programs were continually enrolling new participants, and therefore, data over the time period does not reflect the same target group.

- The Case study data are analyzed together as one sample, but represent a very diverse set of circumstances, from large healing centres to a small project with one staff member, and include Inuit, Métis and First Nations projects, which differ in some key aspects.

- With respect to in-depth analysis of case-study findings and Quarterly reports, differences in reported participation rates were a data limitation.

- A lack of costs data per project per fiscal year within Annual Reports; a shortage of program delivery costs in general, and a lack of any true comparators, inhibit the ability to make a cost effectiveness analysis.

- Aboriginal healing of IRS effects is a highly specialized area, and there is limited research available for comparative purposes and best practice knowledge.

- The nature of project file data (i.e. the sample of 29 projects reviewed) in some cases made analysis difficult, due to what evaluators perceived as possible confusion on the part of project reporters regarding whether to report an indicator as "emerging" or "established"; [Note 20] In some cases, indicators were reported as both [Note 21] and notes attached to reports indicated that this was done because both appeared to be the case. Furthermore, because of the diverse nature of projects; the fact that not all are community based, and some serve a number of communities; reporting whether indicators are "emerging" or "established" in some cases would be extremely challenging for project reporters. For example, in the case where one project serves a number of communities; an indicator may be established in one of the communities but not in others; [Note 22]

- Participants were a targeted, and not a random sample. Due in large part to the severe time constraints of the evaluation, participants were selected by case study sites themselves, rather than chosen randomly by evaluators.

- With respect to in-depth analysis of case-study findings and Quarterly reports, differences in reported participation rates were a data limitation.

Effects of Evaluation on people who have suffered IRS-related trauma

A concern at the outset of the evaluation was the need to protect the safety of program participants who would be taking part, including some program staff who are also Survivors of residential school. The evaluation team found this concern to be well-founded, as we conducted interviews with Survivors. The experience of talking about the topic, even without direct questions regarding IRS experiences, was very difficult for many participants. Health Canada's Health Resolution Support Workers or on-site counselors were ready to de-brief and counsel those who were affected in this way. Although the need for such safety and support is well understood by AHF and Health Canada, it bears reiteration here for evaluators and other researchers, and has clear implications for the ongoing Common Experience Payment (CEP), Independent Assessment Process (IAP) and Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) processes.

Attributes of Outcomes To Program Activities

Accurate assessment of the impacts and outcomes of a community-based social program is recognized in the literature as "usually not possible, even with a carefully designed evaluation study." [Note 23] A more achievable goal is to present evidence that will improve our understanding of the difference made by the program, or its contribution, and to present multiple lines of evidence that speak to program effectiveness. In this evaluation, certainty of attribution of outcomes to program activities is not possible by strict evaluation standards; however, there is a high degree of consistency in the data collected, which increases confidence in the findings.

3.0 Evaluation Findings

3.1 Effectiveness and Success

Background:

Surveys conducted by AHF in 2000, 2002, and 2004 cite an estimated 204,564 participants in AHF-funded healing projects, two-thirds of which had not previously participated in similar activities. [Note 24] The same surveys document an estimated 49,095 individuals who participated in AHF-funded training projects.

In terms of achieving healing outcomes, the AHF Final Report estimated in 2006 that 20 percent of the communities who participated were just beginning healing activities; 65.9 percent of the communities had accomplished some goals, but needed much more work; and 14.1 percent of the communities accomplished many goals. A project goal seen by the AHF as a "pivotal first step to the eventual success of healing endeavours" [Note 25] is the raising of awareness of the history and effects of IRS.

Indicators of Effectiveness and Success:

Over the ten years of its mandate, AHF has refined the understanding of what Survivors, healers and communities understand as indicators of healing of IRS effects. The evaluation used this accumulated knowledge as a guide in selecting indicators of effectiveness and success as areas of investigation for the evaluation.

Accordingly, the level of awareness of IRS and its effects; participation rates and changes in these; the percentage of attendees who are participating in healing for the first time; the degree to which specific needs are being addressed (e.g. youth, elderly, men) the levels of disclosure of abuse; increases in sobriety; the level of support for projects by community leaders; the level of volunteerism supporting projects; the degree to which projects have engaged other service providers and funders for sustainability; time-tested indicators of how effective projects have been at addressing healing needs as defined by communities, were used.

Findings presented below include data from a review of project files for 29 community-based projects, interviews at case study sites, and key informant interviews. The guiding evaluation question was: "To what extent are community-based healing initiatives meeting the healing needs of Aboriginal people affected by Indian Residential Schools?" Some of the charts presented below show less than 29 projects; in these cases, that particular indicator was not reported on for a small number of projects. In cases where the number exceeds 29, projects reported one indicator as both "established" and "emerging" (see note above in Section 2.5).Results are not always unambiguous, due to reporting requirements, as discussed above; for example, the ranking of some indicators as "emerging" may have grown, while that indicator's status as "established" may have decreased over the time period. There are a number of possible explanations for this:

- Project enrolment is growing, which in many cases means that people who are just beginning their healing may outnumber those who are well along in the process; therefore, the assessment of an indicator as "established" will go down, and will rise as "emerging";

- The trajectory of healing is non-linear and long term; the plotting of levels of sobriety, for instance, would be a jagged, rather than a straight line;

- The annual reports assume a community-based project where reporters can report on community conditions. In a number of cases, projects are either based in large urban areas; take clients from across the country; or serve a number of communities with different characteristics. In these cases, reporters would find it difficult to fit their data to the reporting format;

- As the AHF has learned, project success is intimately linked with community dynamics, and factors such as change in community leadership can have major effects on community-level indicators such as volunteerism; and

- A rise in disclosure of sexual abuse would be a positive indicator from the perspective of individuals and families taking the first step towards healing; however, the initial stages following disclosure can also have negative effects on family and community relations that might be reflected in assessments of community conditions.

Intuitively, the reader may feel that a decrease in "established" ranking of an indicator is a negative sign. Evaluators did not make this assessment in most cases, based on the overall findings which show such a dramatic rise in program enrolments (over 40 percent), and the overwhelmingly positive assessment of AHF programs by participants and key informants in communities (some of whom were not directly connected to the program).

Project File Review shows the following:

Projects report that awareness levels are fairly established, both in youth participation/interest as well as Legacy awareness; healing capacity is established in most communities. Indicators of healing such as sobriety, disclosure and other community capacity indicators (i.e. volunteerism) are still emerging. Of 29 projects reviewed, 27.6 percent of projects (n=8 of 29) reported more than half of community healing indicators in 2008/09 as "established".

Program enrolment is growing:

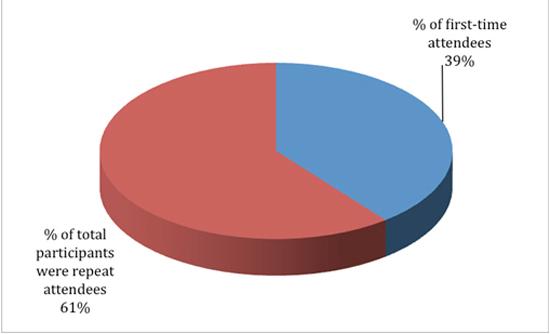

Participation from 2007/08 to 2008/09 increased by 40 percent (7,899 more reported participants in all programs), but case study interviewees noted this was done with no increase in funding or other resources. In 2007/08, 19,642 participants were reported in all programs (for 28 projects), 40 percent of which (7,733) were attending a project activity for the first time. In 2008/09, 27,541 participants were reported in all programs (for 28 projects); 25 percent (6,913) of these participants were attending a project activity for the first time; 11 percent fewer people were listed as a new attendee in 2008/09 than 2007/08.

Figure 2: Number of Participants 2007-08

Figure 2: This figure shows a pie chart indicating the number of participants for all AHF programs in 2007-08. It shows that in that year, 61% of participants were repeat attendees and 39% were first time attendees.

Figure 3: Number of Participants 2008-09

Figure 3: This figure shows a pie chart indicating the number of participants for all AHF programs in 2008-09. It shows that in that year, 75% of participants were repeat attendees and 25% were first time attendees.

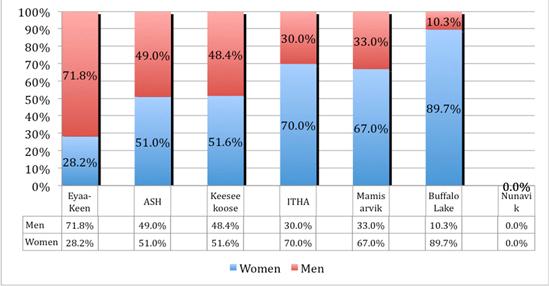

Participation by Target Group and Gender Participation:

A file review for case study sites [Note 26] shows that the majority of program participants are women. This is consistent with normal patterns in Aboriginal communities, where men are known to be a hard-to-reach target group for healing. Given this, the levels of reach to men as a target group for some of the programs (almost 50 percent in some cases) can be taken as an indication of success.

Figure 4: 4th Quarter 2007-08 Gender Participation (Case Studies)

Figure 4: This figure shows a graph which groups the case study participants for the fourth quarter of 2007-08 by gender. Each gender is represented by a different coloured portion of the bars on the graph.

The graph shows that in Eyaa Keen, 28.2% of participants were women and 71.8% were men; in ASH, 51.0% of participants were women and 49.0% were men; in Keeseekoose, 51.6% of participants were women and 48.4% were men; in ITHA, 70.0% of participants were women and 30.0% were men; in Mamisarvik, 67.0% of participants were women and 33.0% were men; and in Buffalo Lake, 89.7% of participants were women and 10.3% of participants were men. Data is not available for the Nunavik case study for 2007-08.

Figure 5: 4th Quarter 2008-09 Gender Participation (Case Studies)

Figure 5: This figure shows a graph which groups the case study participants for the fourth quarter of 2008-09 by gender. Each gender is represented by a different coloured portion of the bars on the graph.

The graph shows that in Eyaa Keen, 72.1% of participants were women and 27.9% were men; in ASH, 62.3% of participants were women and 37.7% were men; in Keeseekoose, 55.7% of participants were women and 44.3% were men; in ITHA, 52.9% of participants were women and 47.1% were men; in Mamisarvik, 54.9% of participants were women and 45.1% were men; in Buffalo Lake, 68.6% of participants were women and 31.4% were men; and in Nunavik, 91.4% of participants were women and 8.6% of participants were men.

File review for the sample of 29 projects shows that in 2007/08, 66.7 percent of projects (n=18 of 27) reported that participation in healing projects by specific groups was an established indicator, and 18.5 percent (n=5 of 27) reported this as "emerging". In 2008/09, 57.1 percent of projects (n=16 of 28) reported participation by specific target groups was established, and 32.1 percent of projects (n=9 of 28) reported as "emerging". The percentage of those reporting no participation by target groups dropped from 14.8 percent (n=4 of 27) in 2007/08 to 10.8 percent in 2008/09, indicating that target groups (such as men, youth, Elders) are increasingly being reached.

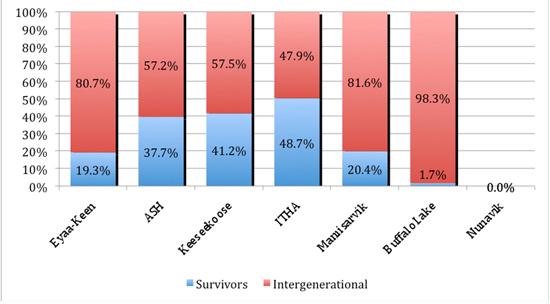

Participation of Survivors in healing activities:

"Survivors", or those who attended residential schools, were the main focus of early healing efforts by projects; over the years, an understanding has emerged that the IRS effects on these individuals was passed on through families and wider social networks. Interviewees noted that Survivors are often reluctant to come out from the refuge of secrecy and the burden of shame to reveal their experiences of abuse and trauma; therefore, the degree of Survivor participation is used as a measure of the effectiveness of healing programs.

Survivor participation is growing:

File review shows that 51.8 percent of projects (n=14 of 27) reported local Survivors involved in awareness-raising activities as an emerging activity; this is an increase of 40 percent over the 2007/08 period.

Figures 6 and 7, below, illustrate survivor participation rates for the case study sites. [Note 27] It is clear that, in most of these projects, Survivors are the minority of project participants. Factors influencing this rate would include the numbers of Survivors in the community; the historical pattern of residential school attendance that would affect the age of Survivors in that particular site; and the particular type of program offered. It was also noted by case study key respondents that there are few actual Survivors remaining, but that the IRS effects have radiated far beyond those individuals.

Figure 6: 4th Quarter 2007-08 Survivor Participation (Case Studies)

Figure 6: This figure shows a graph indicating the rates of IRS Survivor participation in case study groups for the fourth quarter of 2007-08. Survivors and Intergenerational participants are each represented by a different coloured portion of the bars on the graph.

The graph shows that in Eyaa-Keen,19.3% of participants were Survivors and 80.7% were Intergenerational; in ASH, 37.7% of participants were Survivors and 57.2% were Intergenerational; in Keeseekoose, 41.2% of participants were Survivors and 57.5% were Intergenerational; in ITHA, 48.7% of participants were Survivors and 47.9% were Intergenerational; in Mamisarvik, 20.4% of participants were Survivors and 81.6% were Intergenerational; and in Buffalo Lake, 1.7% of participants were Survivors and 98.3% were Intergenerational. Data is not available for the Nunavik case study for 2007-08.

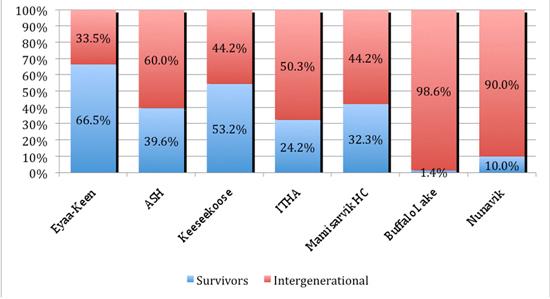

Figure 7: 4th Quarter 2008-09 Survivor Participation (Case Studies)

Figure 7: This figure shows a graph indicating the rates of IRS Survivor participation in case study groups for the fourth quarter of 2008-09. Survivors and Intergenerational participants are each represented by a different coloured portion of the bars on the graph.

The graph shows that in Eyaa-Keen, 66.5% of participants were Survivors and 33.5% were Intergenerational; in ASH, 39.6% of participants were Survivors and 60.0% were Intergenerational; in Keeseekoose, 53.2% of participants were Survivors and 44.2% were Intergenerational; in ITHA, 24.2% of participants were Survivors and 50.3% were Intergenerational; in Mamisarvik, 32.3% of participants were Survivors and 44.2% were Intergenerational; in Buffalo Lake, 1.4% of participants were Survivors and 98.6% were Intergenerational; and in Nunavik, 10.0% of participants were Survivors and 90.0% were Intergenerational.

As noted above, AHF has learned that awareness-raising activities are a "pivotal first step" in the healing process. Interviewees noted that once the knowledge of IRS effects on attendees becomes known, the climate is created for disclosure and the beginning of healing, and family members gain an understanding not only of a major part of their history, but of the behaviour patterns of Survivors. Awareness-raising activities are increasing; in 2008/09, 77.8 percent of projects did such activities, a higher rate than the previous year. Most projects (70.8 percent) in 2008/09 reported including Survivors and their families as an established part of healing.

Evidence of Effectiveness and Success from Participant Surveys:

When asked to rate the effectiveness of healing projects, 62 percent of respondents noted that the programs had contributed to their healing either "quite a bit" or that "most of" their healing had come through attendance at the program., (as Figure 8, below, illustrates.)

Figure 8: This figure shows a pie chart demonstrating the effectiveness of healing projects based on the response of participant surveys to the question, "How much has this project helped you on your healing journey?". 36% of respondents indicated "most" of their healing had come through program attendance; 26% of respondents indicated "quite a bit"; 20% of respondents indicated "some"; 3% of respondents indicated "a little" and 15% of participant surveys indicated "no response".

As an indicator of the effectiveness of programs to connect to other types of healing, program participants were asked the extent to which the AHF program had helped them connect to other types of healing (e.g. rehab, psychotherapy, other counselling), 53 percent of program participant respondents said that the healing program had helped them connect to other kinds of healing required to address the effects of IRS. (See Figure 9, below)

9: Response to "Has this program ever helped you to connect with other kinds of healing you need because of the legacy of residential school?"

Figure 9: This figure shows a pie chart demonstrating the effectiveness of programs to connect to other types of healing based on the response of participant surveys to the question, "Has this program ever helped you to connect with other kinds of healing you need because of the legacy of residential school?". 53% of respondents indicated "yes", 28% of respondents indicated "no", and 19% of survey participants indicated "no response".

Many of those who replied "no" qualified this answer by noting that there were no other accessible healing alternatives available for this specific type of healing. This lack of healing alternatives comparable to AHF healing programs was reiterated by project managers and key informants in interviews.

3.1.1 Building Capacity

Another indicator used to measure effectiveness and success is the degree to which capacity has been built in communities, either through training of healers or engagement of volunteers, particularly Survivors. The building of social capital (of which volunteerism is a part) is recognized by AHF and in the wider literature as a critical component of individual and community healing. One component of this of particular importance in Aboriginal communities is the engagement of Youth, both with their cultural heritage and with Elders. Their degree of engagement is also recognized as an indicator of community capacity.Figure 10: Community indicator - Youth are interested in learning about Aboriginal culture, language and history

Figure 10: This figure shows a graph illustrating aboriginal youth engagement with cultural heritage as an indicator of community capacity in AHF projects. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour on the graph and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, one project reported that youth were not engaged; thirteen projects reported an emerging engagement; fourteen projects reported an established engagement and two projects reported that the trend was not applicable to them. In 2008-09, none of the projects reported that there was no youth engagement; thirteen projects reported an emerging engagement; fifteen projects reported an established engagement and one project reported that the trend was not applicable to them.

File review shows that the building of strong teams of leaders with a variety of skills is firmly established in the majority of projects (n=29), as illustrated in the graph below.

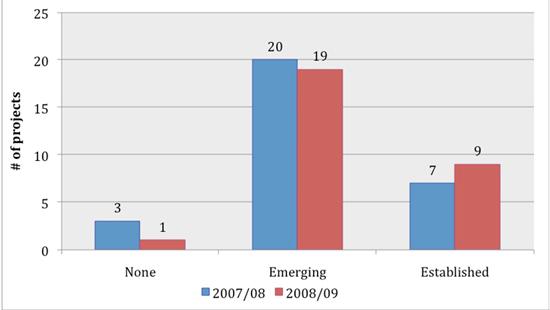

Figure 11: Community indicator - Community has a strong, dedicated healing team

Figure 11: This figure shows a graph illustrating community capacity in AHF projects in terms of building a strong, dedicated healing team with a variety of skills. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, none of the projects indicated that there was no dedicated healing team with a variety of skills; nine projects indicated a team was emerging and twenty-one projects indicated a team was established. In 2008-09, one AHF project indicated that there was no dedicated healing team with a variety of skills; six projects indicated a team was emerging and twenty-two projects indicated a team was established.

While capacity in volunteerism is growing, this indicator is reported to be more in the "emerging" stage than "established"; Volunteerism was reported as "emerging" by 41.4 percent of projects (n=12 of 29 [Note 28]) in 2007/08; this increased to 57.1 percent of projects (n=16 of 28 [Note 29]) in 2008/09. Volunteerism was reported as established by 41.4 percent of projects (n=12 of 29) in 2007/08; but by 32.1 percent of projects (n=9 of 28) in 2008/09. Overall, the number of projects with some volunteering remained relatively stable with 24 in 2007/08 and 25 in 2008/09. The projects reporting no volunteering at all had decreased over the period.

Survivors moving from wanting help to helping others was reported as "emerging" by 66 percent of projects (n=29) in both years.

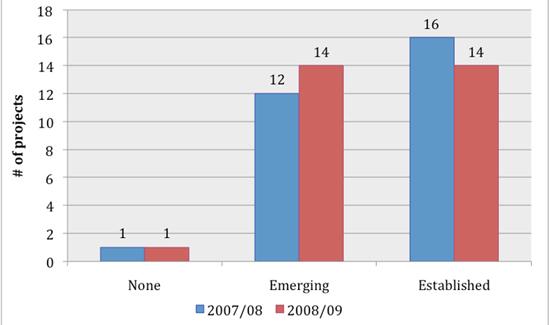

Figure 12: Community indicator - People are volunteering

Figure 12: This figure shows a graph illustrating volunteerism as a community capacity indicator in sample AHF projects. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour on the graph and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, five projects reported that volunteerism was not an established trend; twelve projects reported an emerging trend of volunteerism and twelve projects reported that volunteerism was established. In 2008-09, three projects reported that volunteerism was not an established trend, sixteen projects reported an emerging trend of volunteerism and nine projects reported that volunteerism was established.

The degree of informal help offered between individual and families within communities is another indicator of community capacity for healing; this is reportedly increasing. Figure 13, below shows that in 2007/08, 23 percent of projects (n=7 of 29) reported helping others as established, and this number increased to 31 percent of projects (n=9 of 29) in 2008/09.

Figure 13: Informal Help as an Indicator of Community Capacity

Figure 13: This figure shows a graph that illustrates Survivor volunteerism in sample AHF projects. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour on the graph and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, three projects reported that there was no trend of Survivors volunteering; twenty projects reported an emerging trend of Survivor volunteerism and seven projects reported an established trend of Survivor volunteerism. In 2008-09, one project reported that there was no trend of Survivors volunteering; nineteen projects reported an emerging trend of Survivor volunteerism and nine projects reported an established trend of Survivor volunteerism.

Community involvement and help in general is reported as established by the majority of projects; Figure 14, below, illustrates that 63.3 percent of projects (n=19 of 30 [Note 30]) reported that people are socializing, visiting Elders, and actively contributing to community events. The reported number decreased slightly to 58.6 percent (n=17 of 29) of in 2008/09.

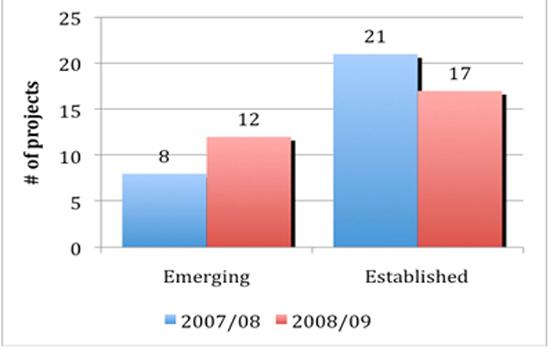

Figure 14: Community indicator – People are socializing, visiting Elders and actively contributing to community events

Figure 14: This figure shows a graph illustrating community involvement as an indicator of healing capacity in sample AHF project communities. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour on the graph and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, one project reported no community involvement; ten projects reported emerging community involvement and nineteen projects reported established community involvement. In 2008-09, one project reported no community involvement; eleven projects reported emerging community involvement and seventeen projects reported established community involvement.

Leadership support appears to be growing:

Another indicator of the degree of capacity for healing in communities is the extent of support and engagement by community leaders. As would be expected, support is more robust than active engagement in projects; however, both indicators show increasing support by community leaders. File review showed that all but one project reported support from community leaders either emerging or established; in terms of participation, 72.4 percent of projects (n=21 of 29) reported participation by community leaders as emerging or established in 07/08, which increased to 83.3 percent (n=25 of 30 [Note 31]) in 08/09. The ranking of this indicator would be sensitive over time to changes in community leadership.

Figure 15: Community indicator – "Community leaders support healing"

Figure 15: This figure shows a graph indicating the healing support community leaders provide in sample AHF project communities. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, one project reported that there was no community leaders' support for healing; twelve projects reported an emerging trend of community leaders' support and sixteen projects reported community leaders' support was established. In 2008-09, one project reported that there was no community leaders' support for healing; fourteen projects reported an emerging trend of community leaders' support and fourteen projects reported that community leaders' support was established.

Figure 16: Community indicator – "Community leaders participate in healing"

Figure 16: This figure shows a graph illustrating community leaders' participation in healing in sample AHF project communities. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, eight projects reported that there was no community leaders' participation in healing; thirteen projects reported an emerging trend of community leaders' participation and eight projects reported that community leaders' participation was established. In 2008-09, five projects reported that there was no community leaders' participation in healing; sixteen projects reported an emerging trend of community leaders' participation and nine projects reported that community leaders' participation was established.

3.1.2 Achieving Healing Outcomes

Indicators used to determine the extent to which programs are achieving healing outcomes include: people speaking openly about their IRS experiences (which is acknowledged as a critical first step in healing); community awareness of the history of residential schools and their effects on individuals and families; the extent to which levels of sobriety have changed in communities.

As Figure 17 below illustrates, file review of these selected indicators shows that the majority of the sampled projects (n=29) report this as an established indicator for their community, and that this has grown between 2007/08 and 2008/09. Disclosure of Residential School experiences is generally reported to be increasing. 54.8 percent of projects (n=17 of 31 [Note 32]) reported that disclosure was established in 2008/09, compared to 46.7 percent (n=14 of 30 [Note 33]) in 2007/08.

Figure 17: Community indicator – People speak openly about their Residential School experiences

Figure 17: This figure shows a graph illustrating healing outcomes in terms of people speaking openly about their IRS experience in sample AHF projects. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, two sample projects reported that there was no trend of people speaking openly about their IRS experiences, fourteen projects reported an emerging trend and fourteen projects reported an established trend. In 2008-09, one sample project reported that there was no trend of people speaking openly about their IRS experiences, thirteen projects reported an emerging trend and seventeen projects reported an established trend.

While all programs report that participants are familiar to some degree with Residential Schools and their community history; the number reporting this as "established" went down from 72.4 percent (n-21 of 29) in 2007/08 to 59 percent (n=17 of 29) in 2008/09.

Figure 18: Community indicator – People are familiar with the Legacy and history of their community

Figure 18: This figure shows a graph indicating awareness of the IRS experience and history within sample AHF project communities. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, eight projects reported an emerging trend of community awareness and twenty-one projects reported an established trend. In 2008-09, twelve projects reported an emerging trend of community awareness and seventeen projects reported an established trend.

As addictions are closely linked to IRS trauma, increased sobriety in a community is recognized as an indicator of progress in healing. Project files show that the majority of projects in the sample report this as an "emerging" indicator, and that the percentage of projects reporting this increased to some extent between 2007/08 and 2008/09. (see Figure 19, below)

Figure 19: Community indicator – Increased sobriety in the community

Figure 19: This figure shows a graph indicating the extent to which levels of sobriety have changed in AHF project communities. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, two projects reported that there was no increase in sobriety, nineteen projects reported an emerging trend of increased sobriety, six projects reported an established trend, and two projects reported that the trend was not applicable to them. In 2008-09, two projects reported that there was no increase in sobriety, twenty-three projects reported an emerging trend of increased sobriety, and four projects reported an established trend.

There were particular instances of success noted in the literature and interviews with key informants. One of these is Mamisarvik Healing Centre, an Inuit-focused project in Ottawa, which uses a screening tool on intake. Analysis of that data indicated the presence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in approximately 85 percent of clients. Following eight weeks of treatment, the indicators for PTSD are "significantly reduced or gone for most". [Note 34]

A number of interviewees reported their knowledge of decreases in suicide rates and child apprehensions, and increases in intergenerational communication and interaction, particularly between Elders and youth, as a result of AHF healing programs. A program in Saskatchewan reported successfully rehabilitating an individual in his 50's, an IRS attendee for many years who was sexually abused, who had been incarcerated for most of his adult life, including for sex offences. [Note 35]

3.1.3 Challenges to Administration and Delivery

Challenges to program administration and delivery noted by Key Respondents (case study participants, including: program boards, directors, healers and other staff; and other key respondents such as experts) include the following:

- Funding: both a shortage of funds in the face of rising enrolments and increased demand for services, and the challenge (over the entire funding period) of uncertainty of funding. This was by far the most cited challenge by case study interviewees. One of the aspects of this that is affecting current projects, including those in the case study sample, is the impending closure of all but the healing centres in March 2010; (the healing centres receive operational funding and will continue until March 2012). Interviewees noted that the uncertainty of the winding-down period makes it difficult to retain staff;

- Staffing: Projects have found it difficult to attract qualified staff, both those trained in mainstream healing modes, and Aboriginal cultural experts/healers;

- Training: Respondents note that there have not been enough training opportunities for existing staff to build healing capacity to required levels within communities. In particular, staff report being challenged by complex healing needs and crisis situations. The same challenge was noted in the AHF Final Report (Vol. 1, p. 171), which noted the consistent requests from project staff for "targeted, advanced training to meet the needs";

- Reports indicate that the increased demand for project services is due, at least in part by, the CEP, IAP andTRC, both by triggering disclosure and the seeking of healing by more Survivors, and by demands on projects for assistance in navigating the CEP and/or IAP processes. As a result, projects have reported an increase in demand for their services without an increase in funding or staffing; in some cases, healing services have been pre-empted by the immediate demands of Survivors needing assistance withCEP/IAP processes (see Section 3.2.2, below, for a more detailed discussion of this). It was noted by some respondents that clients state their preference for AHF programs over government programs, because it is an Aboriginal organization, which they can trust; [Note 36]

- Travel and childcare costs prohibit participation of some potential participants (the scale of this challenge differs according to urban or rural location of project);

- Community determinants of health (i.e. social indicators) remain challenging: (e.g.. poverty, housing conditions, family violence, addictions, sexual abuse, suicide and grief); there is still a high level of need for healing. Many interviewees remarked that the needs that have been addressed are "just the tip of the iceberg";

- Limited support from leadership in some cases: while projects file review noted this was improving, it was reported as a challenge in some case study sites;

- Project staff are strained by project demands, with little time to devote to seeking outside resources;

- Different cultural approaches regarding models of healing that should be employed (e.g. Medicine Wheel);

- Limited alternative healing resources in community context for referral of complex needs clients;

- There are limited resources for follow-up care of program clients;

- Religious opposition in some communities to healing activities;

- There is a need for more Inuit-specific services;

- Inuit projects were started later than others; hence the healing period for Inuit Survivors has been shorter; and

- Inuit projects are challenged by the reality of much higher costs in the North.

Challenges noted in previous evaluations conducted by the AHF (Kishk Anaquot Health Research 2001, 2002, 2003), include fear, denial and resistance; and the challenge of engaging men in programs. It is notable that these challenges are rarely mentioned now, and serves as an indication of the progress that has been achieved in these areas, in terms of raising awareness and reaching out to men, a target group notoriously difficult to reach.

Resistance and opposition to healing programs within communities are seldom cited now as challenges, indicating an improvement in this indicator of community capacity.

3.1.4 Sustainability of Initiatives

Background:

Linkages and partnerships, particularly funding agreements, were selected as key indicators of project sustainability. The Funding Agreement stipulates that "In order to be eligible, projects…shall establish complementary linkages, where possible in the opinion of the Board, to other health/social programs and services (federal / provincial / territorial / Aboriginal)" (AHF Funding Agreement 2007). National survey results show that 85 percent of projects were addressing the legacy of residential schools in collaboration with other agencies or organizations (Degagné 2008).

Partnerships and linkages:

Review of the selected sample of project files for the two years (n=29) shows that:

- In 2007/08, 38 percent of projects reported having no partner funding of any type; this had increased to 45 percent in the following year.

- The majority of projects have partner funding support of less than $10,000 per year.

- Roughly $1.4 million of support was reported in 2007/08, and just over $1.8 million in 2008/09; however, over $850,000 was from a single contribution to one program. Just over $950,000 was reported in total funding partnerships for the 28 others, a decrease of over $450,000.

Figure20: Partnership support to projects by year

Figure 20: This figure shows two pie charts which indicate levels of funding support from Partnerships in sample AHF projects. There are four different funding level groups, each represented by a colour, and the charts show the percentage representation for each group. The first chart illustrates data collected for the year 2007-08. The chart shows that 38% of the sample projects received no Partnership funding, 17% received less than $10 000, 24% received between $10 000 and $100 000, and 21% received more than $100 000. The second chart illustrates data collected for the year 2007-08. The chart shows that 45% of the sample projects received no Partnership funding, 17% received less than $10 000, 21% received between $10 000 and $100 000, and 17% received more than $100 000.

- Other partnership initiatives included private charity linkages, Legacy of Hope and other IRS support organizations, municipal support, and justice agencies support.

- Many projects listed partnerships with other agencies but provided no details on in-kind funding; these were primarily described as cross-referrals, collaborative programming, or services/expertise the AHF project provided to other agencies.

- Health, Education and Addictions agency partnerships were the most commonly cited linkages.

Figure 21: Identified Partnerships by Type, 2007-08

Figure 21: This figure shows a graph indentifying the types of Partnerships made with AHF projects in 2007-08. There are twelve types of Partnerships listed and the graph shows the number of projects listing each type of Partnership. The projects cited types of Partnerships as follows: Nineteen projects claimed Partnership with health organizations; nineteen with organizations related to education; fifteen with local aboriginal government; thirteen with social services; thirteen with CFS; sixteen with addictions organizations; thirteen with the police/RCMP.; eleven with youth organizations; twelve with provincial/federal governments; eight with shelters/assault centres; fourteen with Elders' groups and six with other types of organizations.

Linkages and Cross-referrals:

In both 07/08 and 08/09, slightly more than half of projects whose files were reviewed (51.9 percent or n=14 of 27 [Note 37] projects and 51.7 percent or n=15 of 29 projects respectively) reported referrals from mainstream services to community based healing initiatives as "established". Mainstream services and agencies include those at all levels, including local municipal, regional Aboriginal provincial/territorial organizations; Survivor organizations, provincial and federal government departments.

Figure 22: Community Indicator – Referrals from Mainstream Services

Figure 22: This figure shows a graph indicating trends in referrals from mainstream services to community-based healing initiatives in AHF projects. Data collected for the years 2007-08 is represented by one colour and data collected for the years 2008-09 is represented by another. In 2007-08, two projects reported that there were no referrals from mainstream services; eleven projects reported an emerging trend in referrals and fourteen projects reported an established trend in referrals. In 2008-09, two projects reported that there were no referrals from mainstream services; twelve projects reported an emerging trend in referrals and fifteen projects reported an established trend in referrals.

Case study findings are that while linkages for cross-referrals and some sharing of resources is common amongst the case studies, most projects have limited resources for continued funding; in part because there are few, if any, agencies with a matching mandate as suitable partners. As a result, many projects are sustainable from the point of view of continued need and supportive referral environments to existing (although limited) resources, but not in terms of funding. A number of the case study projects reported receiving referrals from mainstream service providers such as mental health counselors and social workers; for example, the First Nations House of Healing on Vancouver Island showed a 65 percent increase in referrals from other agencies in the period under review.

Interviewees noted also that Aboriginal clients prefer AHF healing programs to government and other mainstream services because they are perceived as offering Aboriginal services in a culturally safe environment, and that they are entitled to such a choice.

3.2 Impacts

3.2.1 Program Impacts

Case study interviews provided the following information on the reported impacts of healing projects; these were reported by program participants, staff/healers, community leaders, and frontline workers in communities and partner agencies.

- Learning to take action and responsibility for one's own health and healing was the most often cited impact by program participants;

- Increased community capacity for healing as indicated by increased awareness; decrease in anger and resistance to healing initiatives; "healing" is now an acknowledged and better understood concept. Interviewees who were family members of Survivors noted that, by learning the history of IRS and its impacts, they for the first time understood the Survivors in their family. Increased awareness was the second most-often mentioned impact of healing programs by program participants in case study interviews, and this was linked to changed attitudes towards family members (particularly Survivors);

- Increase in cultural knowledge, decreased shame in Aboriginal identity and increased pride and celebration of culture. Many respondents cited the learning or re-connection with their culture as the key to a recovered sense of self and one's place in the world, from which a number of positive actions could flow;

- Increased pride and self-esteem has led to achievements in education and work life for many participants;

- Reported healing of trauma and negative emotions and the acquisition of "tools" for continuance of self-care in this area; one mental health expert's description of this approach was to say that "healing is a key precondition for people [who have been institutionalized and therefore dependent] to find their pathway to self-care";

- Reported decrease in sense of isolation through realization and sharing of many similar stories of IRS effects; programs seen as a "safe place" to disclose experiences and begin healing;

- Reported increase in intrapersonal/informal community supports as knowledge of impacts spreads in communities (i.e. an increase in social support and social cohesion, an aspect of social capital);

- Reported improved family relationships as a result of control of negative emotions and heightened empathy resulting from increased knowledge of IRS effects;

- Reuniting of mothers and children taken into care after mothers completed healing programs;

- Less tolerance for sexual abuse at the community level, attributed to increased disclosures and heightened sense of personal pride and autonomy ("empowerment");

- Reported increase in connections between Elders and youth, particularly those intergenerationally impacted;

- Many respondents noted the program enabled them to live life more fully; the comment often made was "this program saved my life!"

- The beginning of hope for positive change; and

- In many cases, increased cooperation between social/health agencies indicated by cross-referrals, shared training, shared resources.

3.2.2 Impacts of the Settlement Agreement on Healing Needs

As the focus of this evaluation is on the funding arising from the Settlement Agreement, and the funding period from its inception until the present, the impacts of this significant change in the context of Aboriginal healing from IRS was identified as an evaluation issue to investigate. The challenges to program administration and delivery attributed to the effects of the Settlement Agreement processes are discussed above; here we outline the most frequent responses to the question: "Since the Settlement Agreement has been in place, and compensation of various kinds has been offered, do you think this has had effects on the healing needs of communities, and if so, what would those effects be?"